Published online Aug 26, 2012. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v4.i8.264

Revised: June 20, 2012

Accepted: June 27, 2012

Published online: August 26, 2012

Coronary artery anomalies are usually encountered as coincidental findings during coronary angiography or at autopsy. Life threatening symptoms, such as arrhythmias, syncope, myocardial infarction, or sudden death, can occur in up to 20% of patients. However, the majority of anomalies (80%) are benign and asymptomatic. A single coronary artery (SCA) is one of the most rarely seen coronary anomalies with an incidence of 0.05%. We report the case of a 55-year old male patient who presented with symptoms of chest pain associated with an acute myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography revealed an anomalous left main coronary artery (LMCA) originating from the right coronary ostium, and an occluded distal right coronary artery. The occluded distal right coronary artery was successfully treated by thrombosuction and stenting. In order to confirm the origin and course of the SCA, multi-slice computed tomography (MSCT) of the heart was performed after coronary angiography. MSCT showed that the anomalous LMCA originated from the right coronary artery ostium and then passed the interventricular septum, instead of being intra arterial, and under the right ventricular infundibulum. The anomalous LMCA was classified as R-II S subtype according to Lipton’s classification.

- Citation: Liesting C, Brugts JJ, Kofflard MJM, Dirkali A. Acute coronary syndrome in a patient with a single coronary artery arising from the right sinus of Valsalva. World J Cardiol 2012; 4(8): 264-266

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v4/i8/264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v4.i8.264

A single coronary artery (SCA), defined as an artery that arises from the aortic trunk from a single coronary ostium and supplies the entire heart, is rare. Coronary anomalies are inborn errors, and life-threatening symptoms, such as arrhythmias, syncope, myocardial infarction, or sudden death, can occur in up to 20% of patients. However, the majority of anomalies (80%) are benign and asymptomatic[1]. They are usually encountered as coincidental findings during coronary angiography or at autopsy.

The incidence of a left main coronary artery (LMCA) originating from the ostium of the right coronary artery (RCA) is very low (0.05%)[2]. There are several classifications for coronary artery anomalies. Lipton proposed a classification of solitary coronary arteries in 1979 which combined two previous classifications defined by Smith in 1950 and Ogden and Goodyer in 1970.

A 55-year old man presented at the emergency department with progressive typical anginal symptoms for a few days. The patient’s medical history showed no cardiovascular diseases and his sole risk factor was current smoking. Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 115/80 mmHg with a regular pulse of 64 beats per minute, heart murmurs were absent and there were no signs of heart failure.

Laboratory assessment disclosed evidence of myocardial injury, but was otherwise unremarkable: troponin T (0.49 μg/L, normal < 0.10 μg/L) and creatine kinase (805 E/L, normal < 200 E/L). Electrocardiography demonstrated a sinus rhythm of 68 beats per minute and ST depression of 2 mm in leads V2-V4. The patient was admitted to our hospital with a non-ST elevated myocardial infarction and, after treatment with appropriate medication, his chest pain disappeared.

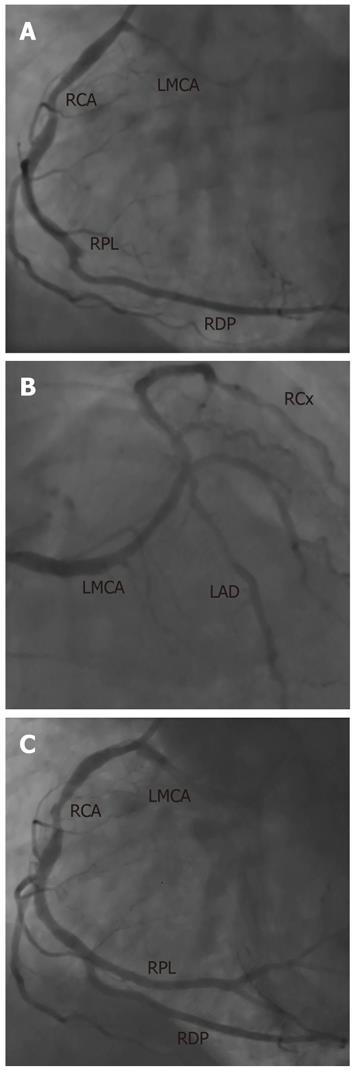

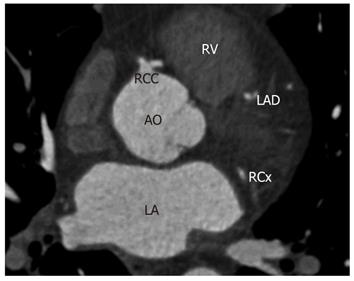

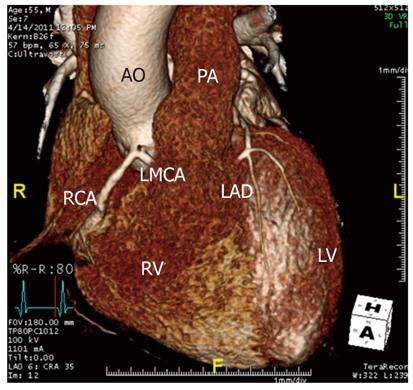

The day after admission, chest pain reappeared and the electrocardiogram now showed sinus rhythm with ST elevation in leads II, III, aVF and 1 mm ST depression in V2-V5 without the presence of pathological Q waves. Thereupon, coronary angiography was performed immediately. The angiogram demonstrated a SCA: the LMCA originated from the ostium of the RCA (Figure 1A and B). There was a borderline lesion in the proximal RCA and an occlusion of the posterolateral branch of the RCA (Figure 1A). Thrombosuction and stenting of the occluded branch was performed successfully (Figure 1C). In order to confirm the origin and course of the anomalous LMCA, multi-slice computerized tomography (MSCT) of the heart was performed (Figure 2). The results showed the anomalous LMCA originating from the ostium of the RCA and passing the interventricular septum, rather than being intra arterial, then under the right ventricular infundibulum (Figure 3). The anomalous LMCA was classified as R-II S subtype (Table 1).

| Ostial location | R | Right sinus of Valsalva |

| L | Left sinus of Valsalva | |

| Anatomical distribution | I | Single coronary artery with normal right or left coursing (RC or LC) |

| II | After leaving the right or left sinus the single coronary artery crosses at the base of the heart as a large transverse trunk in order to supply the contralateral coronary artery | |

| III | Single coronary artery arising from the right sinus, with the left anterior descending and circumflex arteries from separate coronary artery trunks instead of a single trunk immediately at the exit | |

| Course of the transfer branch | A | Anterior to the large vessels (anterior to the right ventricle) |

| B | Between the aorta and pulmonary artery | |

| P | Posterior to the large vessels | |

| S | Septal type (above the interventricular septum) | |

| C | Combined type |

Most coronary artery anomalies are asymptomatic and are usually encountered as coincidental findings during coronary angiography or autopsy[1]. The most commonly seen coronary artery anomaly include the left anterior descending and ramus circumflex (RCx) arteries arising from separate ostia in the left sinus of Valsalva. The RCx artery arising from the right sinus of Valsalva, the RCA arising from the left sinus of Valsalva, and coronary artery fistulae are also commonly seen. An isolated SCA anomaly is one of the most rarely seen coronary anomalies[3]. These coronary anomalies are classified by Lipton according to the site of origin from the left and right coronary arteries, the anatomical distribution on the ventricular surface, and according to the relationship with the ascending aorta and the pulmonary artery (Table 1)[3]. Our case provides an example of a SCA arising from the right sinus of Valsalva and which had an initial common trunk that gave rise to both the RCA and a long LMCA which followed a prepulmonic intraseptal course (R-II S subtype), which is rare and non-malignant[4]. In patients with a SCA and an intra arterial course, sudden death may take place since the coronary artery is compressed between the aorta and the pulmonary artery during vigorous exercise[4].

Coronary angiography is the gold standard for the evaluation of coronary artery disease. However, in the case of coronary anomalies, further evaluation by MSCT or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is recommended to determine the course of the anomaly and prognosis. The excellent spatial resolution of MSCT makes this technique very suitable to detect the relationship of the anomalous vessels with the aorta, pulmonary artery and cardiac structures[5]. It is a safe technique and provides detailed 3-dimensional reconstructions that may be difficult to obtain with invasive angiography.

In our patient, we diagnosed the SCA by coronary angiography and further delineated the course of the anomalous coronary artery in relation to the aorta and pulmonary artery by MSCT. The management of patients with a SCA includes a conservative approach in most patients, but in the case of an intra arterial course, coronary artery bypass grafting is the treatment of choice to prevent sudden death[5].

The incidence of a LMCA originating from the ostium of the RCA is very low (0.05%). Our case of a 55-year old male patient with this coronary anomaly underwent MSCT to confirm the origin. The anomalous LMCA passed the interventricular septum and therefore was classified as R-II S subtype according to Lipton’s classification.

Peer reviewers: Hiroyasu Ueda, MD, PhD, Department of Cardiology, Sumitomo Hospital, 5-3-20, Nakanoshima, Kita-ku, Osaka 530-0005, Japan; Zhonghua Sun, Professor, Department of Medical Imaging, Curtin University of Technology, Kent Street, Perth 6102, Australia

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Yamanaka O, Hobbs RE. Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1990;21:28-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1278] [Cited by in RCA: 1359] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Desmet W, Vanhaecke J, Vrolix M, Van de Werf F, Piessens J, Willems J, de Geest H. Isolated single coronary artery: a review of 50,000 consecutive coronary angiographies. Eur Heart J. 1992;13:1637-1640. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lipton MJ, Barry WH, Obrez I, Silverman JF, Wexler L. Isolated single coronary artery: diagnosis, angiographic classification, and clinical significance. Radiology. 1979;130:39-47. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Basso C, Corrado D, Thiene G. Congenital coronary artery anomalies as an important cause of sudden death in the young. Cardiol Rev. 2001;9:312-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thomas D, Salloum J, Montalescot G, Drobinski G, Artigou JY, Grosgogeat Y. Anomalous coronary arteries coursing between the aorta and pulmonary trunk: clinical indications for coronary artery bypass. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:832-834. [PubMed] |