Published online Jul 26, 2012. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v4.i7.231

Revised: June 4, 2012

Accepted: June 11, 2012

Published online: July 26, 2012

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) septicemia is associated with high morbidity and mortality especially in patients with immunosuppression, diabetes, renal disease and endocarditis. There has been an increase in implantation of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED) with more cases of device-lead associated endocarditis been seen. A high index of suspicion is required to ensure patient outcomes are optimized. The excimer laser has been very efficient in helping to ensure successful lead extractions in patients with CIED infections. We present an unusual case report and literature review of MRSA septicemia from device-lead endocarditis and the importance of early recognition and prompt treatment.

- Citation: Anusionwu OF, Smith C, Cheng A. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator lead-related methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: Importance of heightened awareness. World J Cardiol 2012; 4(7): 231-233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v4/i7/231.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v4.i7.231

The implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) reduces total mortality in patients with structural heart disease[1]. Infections of these devices have increased over the last two decades[2] and are associated with an 8.4%-11.6% increased risk of mortality when compared to hospitalizations attributed to noninfectious, cardiac device-related complications[3]. We present a case and literature review of persistent methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) septicemia that was found to be secondary to a biventricular ICD infection without any signs of device pocket infection.

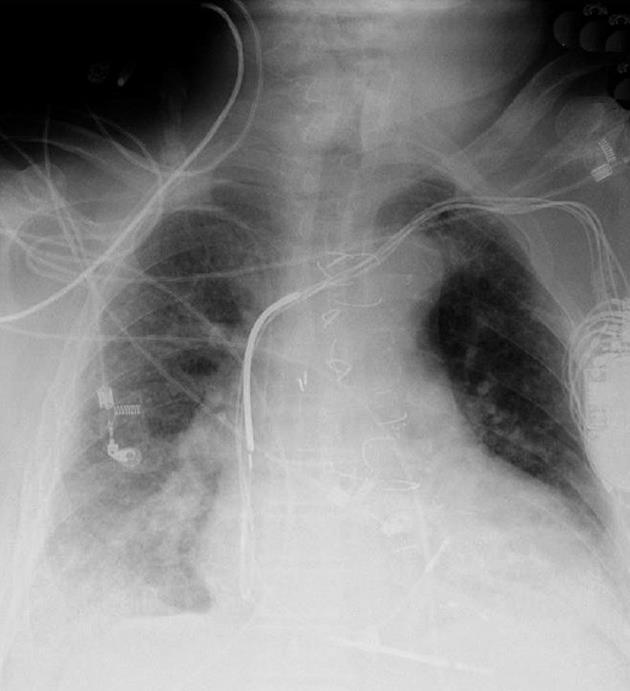

An 80 year-old male with coronary artery disease status post coronary artery bypass graft surgery and implantation of a biventricular ICD 15 years ago presented with a 2-d history of fever and abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed fever, tachycardia and hypotension. Initial blood work revealed acute renal failure and MRSA bacteremia. His chest X-ray (CXR) is seen in Figure 1. Despite 2 wk of appropriate antibiotics, his blood cultures remained positive.

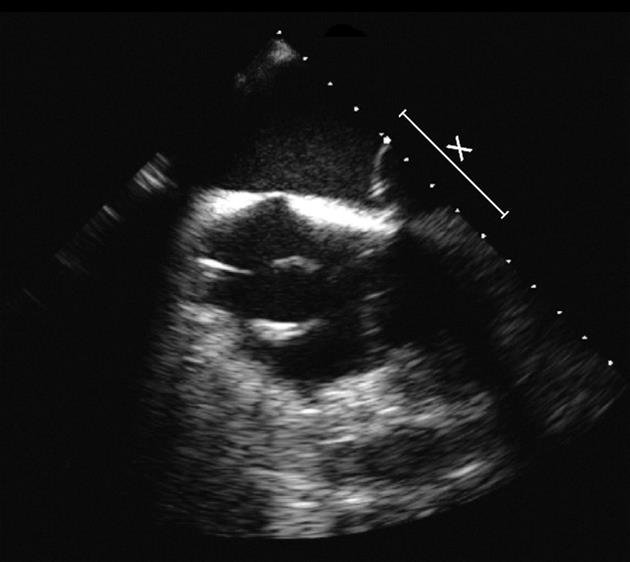

The patient’s central lines were removed. Comprehensive radiologic evaluations were unremarkable. The skin overlying his implantable device was normal. Further workup with a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) revealed 1.5 cm vegetation in his right atrium contiguous with his device leads as seen in Figure 2. He was subsequently referred for device extraction.

Under general anesthesia, an incision was made over the ICD generator. The ICD was encased in a capsule of fibrous tissue. A capsulotomy was performed and all four indwelling leads were completely removed with the use of a 16Fr excimer laser sheath (Spectranetics, Colorado Springs, CO). Microbiologic specimens taken at the time of the procedure grew MRSA. He was continued on intravenous Vancomycin with eventual clearance of his blood cultures. He underwent reimplantation of a new biventricular ICD and was discharged in stable condition.

Device-related infections are increasing and can often present with nonspecific signs and symptoms. Often these infections are secondary to skin-related flora. In fact, S. aureus bacteremia can be the sole manifestation of device infection in many individuals[4]. A high index of suspicion is necessary in patients with an ICD who present with septicemia and no evidence of pocket infection. Echocardiography is usually utilized to help in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiac implantable electronic device infections (CIED). Eight percents of vegetations on pacemaker leads can be seen by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) as compared to 80% via TEE hence TEE should be used early in cases with a high suspicion for CIED[5]. In our case, TEE should have been used early in order to help guide the diagnosis and treatment of his condition. In a recent study, 91% of their patient population had TEE performed which helped in their outcomes with a calculated TTE sensitivity of 25.5%[6]. In urgent cases like septic or cardiogenic shock accompanied by a delay in the decrease of inflammatory markers (especially if there is a high suspicion for lead-associated endocarditis), TEE should be done immediately to help in improving the patients’ treatment outcomes[7].

In a recent study by Tarakji et al[8], 41% of 412 patients had an intact-appearing pocket despite having systemic signs and symptoms of infection with an in-hospital mortality of 4.6%. The authors noted that Staphylococcus species have consistently been the most common pathogen isolated in most cases of CIED with 44% of S. aureus infections being MRSA. In the Multicenter Electrophysiologic Device Infection Cohort, they found that a remote source of infection was usually present 38% of the time in late lead-associated endocarditis (LAE) unlike 8% for early LAE (P < 0.01). The in-hospital mortality was low for the two groups, 7% for early LAE and 6% for late LAE[9]. Patients with an implantable cardiac device who present with MRSA or methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia should be aggressively screened for device infections especially if there are no other identifiable sources. The data are less clear for gram-negative bacteremia.

Transient bacteremia could occur during brushing of the teeth, tooth extraction or dental cleaning but the risk of its resulting in persistent MRSA bacteremia is low[10]. The American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis before dental procedures considered patients with cardiac devices as low risk and thus not requiring routine prophylaxis[11]. Rather, improved oral health and hygiene has been encouraged to reduce the incidence of transient bacteremia that could progress to lead- associated endocarditis[11]. In patients who have had previous infective endocarditis or prosthetic cardiac valves, it is recommended that they should receive antimicrobial prophylaxis before dental procedures[12].

When device-related infections occur, complete extraction is necessary to eradicate the infection. Cardiac implantable electronic device extraction is usually performed in tertiary referral centers because of the availability of expertise and the need for cardiac surgery back-up[13]. There are several methods used in lead extraction that includes traction/countertraction, grasping devices, and excimer laser sheaths aimed to debulk connective tissue surrounding leads. The ultraviolet excimer laser is particularly effective in facilitating extraction with minimal risk of perforating the vein or heart especially with chronic indwelling leads that have significant amounts of fibrous tissue surrounding them[14]. Our patient was able to undergo lead extraction without complications using the excimer laser. His follow up TTE and CXR were unremarkable.

Complications related to lead extractions have been studied in two large clinical trials. The Plexes Trial prospectively randomized 301 subjects with 465 chronic pacemaker leads and found a 94% procedural success rate in the laser group with 1.96% associated major complication[15]. In the Lexicon study, the all-cause in-hospital mortality for laser-assisted lead extraction was 1.86%: 4.3% when associated with endocarditis, 7.9% when associated with endocarditis and diabetes, and 12.4% when associated with endocarditis and creatinine ≥ 2[16]. According to the Heart Rhythm consensus statement, major complications include death, cardiac and vascular avulsion or tear, pulmonary embolism, respiratory arrest, stroke and pacing system related infection of non-infected site[13]. Some of the risk factors for complications include female gender, long implantation time, and lack of experience of the operator and ICD lead type[14].

Finally, it is important to ensure that blood cultures are negative before implanting another ICD device. Current AHA guidelines recommend a period of 72 h of negative blood cultures before implantation of a new CIED in patients with previously positive lead vegetation on TEE and blood cultures[17].

Peer reviewer: Yves D Durandy, MD, Perfusion and Intensive Care, Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, Institut Hospitalier J Cartier, Avenue du Noyer Lambert, 91300 Massy, France

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Lenz C, Dietze T, Möller M, Schöbel W, Wicke J, Kellner HJ, Gradaus R, Neuzner J. Incessant ventricular tachycardia, refractory to catheter ablation, in an ICD patient terminated by ICD lead extraction: a case report. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98:803-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sohail MR, Hussain S, Le KY, Dib C, Lohse CM, Friedman PA, Hayes DL, Uslan DZ, Wilson WR, Steckelberg JM. Risk factors associated with early- versus late-onset implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infections. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2011;31:171-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sohail MR, Henrikson CA, Braid-Forbes MJ, Forbes KF, Lerner DJ. Mortality and cost associated with cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1821-1828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Uslan DZ, Dowsley TF, Sohail MR, Hayes DL, Friedman PA, Wilson WR, Steckelberg JM, Baddour LM. Cardiovascular implantable electronic device infection in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH, Friedman PA, Hayes DL, Wilson WR, Steckelberg JM, Jenkins SM, Baddour LM. Infective endocarditis complicating permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:46-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rodriguez Y, Garisto J, Carrillo RG. Management of cardiac device-related infections: A review of protocol-driven care. Int J Cardiol. 2011;Oct 25; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sedgwick JF, Burstow DJ. Update on echocardiography in the management of infective endocarditis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14:373-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tarakji KG, Chan EJ, Cantillon DJ, Doonan AL, Hu T, Schmitt S, Fraser TG, Kim A, Gordon SM, Wilkoff BL. Cardiac implantable electronic device infections: presentation, management, and patient outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1043-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Greenspon AJ, Prutkin JM, Sohail MR, Vikram HR, Baddour LM, Danik SB, Peacock J, Falces C, Miro JM, Blank E. Timing of the most recent device procedure influences the clinical outcome of lead-associated endocarditis results of the MEDIC (Multicenter Electrophysiologic Device Infection Cohort). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Forner L, Larsen T, Kilian M, Holmstrup P. Incidence of bacteremia after chewing, tooth brushing and scaling in individuals with periodontal inflammation. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison M, Bolger A, Cabell CH, Takahashi M, Baltimore RS. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1773] [Cited by in RCA: 1413] [Article Influence: 78.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Allen U. Infective endocarditis: Updated guidelines. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010;21:74-77. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Byrd CL, Bongiorni MG, Carrillo RG, Crossley GH, Epstein LM, Friedman RA, Kennergren CE, Mitkowski P. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management: this document was endorsed by the American Heart Association (AHA). Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1085-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 793] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Farooqi FM, Talsania S, Hamid S, Rinaldi CA. Extraction of cardiac rhythm devices: indications, techniques and outcomes for the removal of pacemaker and defibrillator leads. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1140-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wilkoff BL, Byrd CL, Love CJ, Hayes DL, Sellers TD, Schaerf R, Parsonnet V, Epstein LM, Sorrentino RA, Reiser C. Pacemaker lead extraction with the laser sheath: results of the pacing lead extraction with the excimer sheath (PLEXES) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1671-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wazni O, Epstein LM, Carrillo RG, Love C, Adler SW, Riggio DW, Karim SS, Bashir J, Greenspon AJ, DiMarco JP. Lead extraction in the contemporary setting: the LExICon study: an observational retrospective study of consecutive laser lead extractions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:579-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Baddour LM, Epstein AE, Erickson CC, Knight BP, Levison ME, Lockhart PB, Masoudi FA, Okum EJ, Wilson WR, Beerman LB. Update on cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections and their management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:458-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 743] [Cited by in RCA: 760] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |