Published online Jun 26, 2012. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v4.i6.214

Revised: June 7, 2012

Accepted: June 14, 2012

Published online: June 26, 2012

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy typically affects post-menopausal women under severe psychological or physical stress; it also has been reported to develop after medical procedures or surgery. We herein report the rare case of a 30-year-old woman who presented with an episode of ventricular fibrillation after a very complicated cesarean delivery and was successfully resuscitated. Subsequent electrocardiography and echocardiography showed a typical Takotsubo pattern. Within 3 wk, left ventricular systolic function returned to normal.

- Citation: Bortnik M, Verdoia M, Schaffer A, Occhetta E, Marino P. Ventricular fibrillation as primary presentation of takotsubo cardiomyopathy after complicated cesarean delivery. World J Cardiol 2012; 4(6): 214-217

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v4/i6/214.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v4.i6.214

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), also known as “transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome” or “stress-induced cardiomyopathy”, is characterized by reversible left ventricular dysfunction, chest pain or dyspnea, new electrocardiographic abnormalities (ST-segment elevation and/or T-wave inversion) and minor elevations in cardiac enzymes in the absence of significant coronary artery disease[1].

The pathophysiological mechanism of this syndrome is not completely understood, and several possibilities have been suggested such activation of α- and β-adrenoceptors as triggers of stress-induced physiologic and molecular changes, and cathecolamine-mediated myocardial stunning as the result of epinephrine-mediated effects on cardiomyocytes[2-4]. Patients affected by the disease are predominantly postmenopausal women who experience intense emotional or physical stress and subsequently develop chest pain and dyspnea[5]. Although cases of TCM in young women during pregnancy and even during delivery have already been described[6-8], this entity in young premenopausal women appears to be rather unusual.

We herein report a rare case of Takotsubo-like cardiomyopathy which occurred in a young woman after hystero-ovariectomy performed for uterine apoplexy after cesarean delivery who presented with cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation.

A 30-year-old healthy Asian woman with no risk factors for coronary artery disease was admitted to our hospital at 40 wk’ gestation for elective cesarean delivery because of a macrosomic fetus. Her past medical history was unremarkable. Routine electrocardiography (ECG) recorded prior to delivery was normal.

Cesarean delivery was performed following the administration of standard spinal anesthesia, and oxytocin was administered for easy release of the placenta. Two hours later, the patient underwent emergency hysterectomy and right ovariectomy for hemorrhagic shock due to uterine apoplexy. One hour later, she experienced a cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation; advanced cardiac life support maneuvers and step-by-step adrenaline was immediately performed; sinus rhythm was then restored after 6 DC shocks.

Initial laboratory values showed anemia (hemoglobin 7.6 g/dL), hematocrit 23.2%, low platelet count (95 × 103/μL), normal renal and liver function and normal serum electrolytes. Cardiac injury markers were increased (troponin I 2.47 ng/mL, creatine kinase isoenzyme MB 8.97 ng/mL).

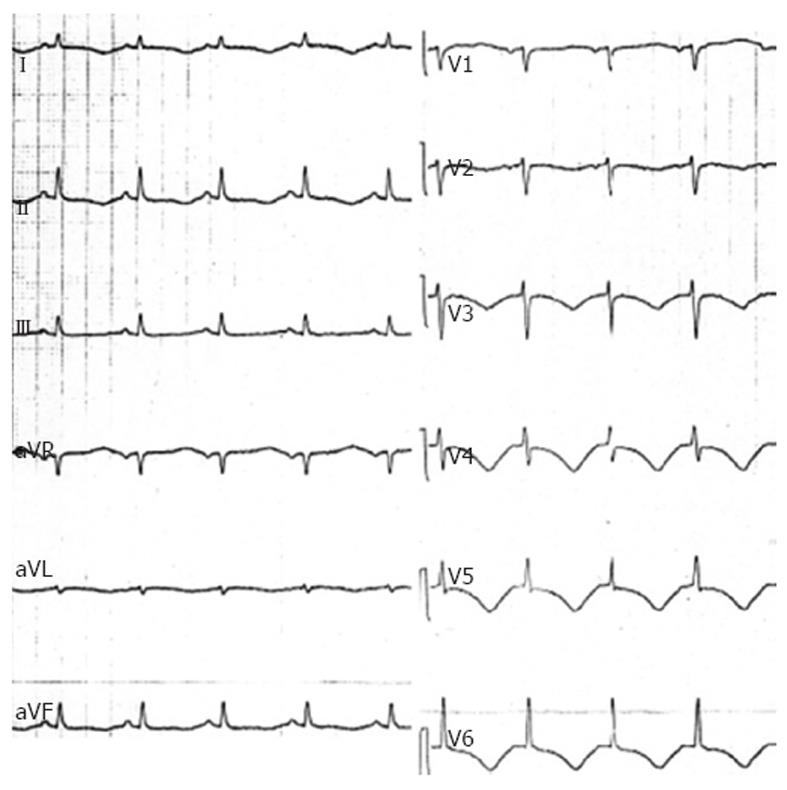

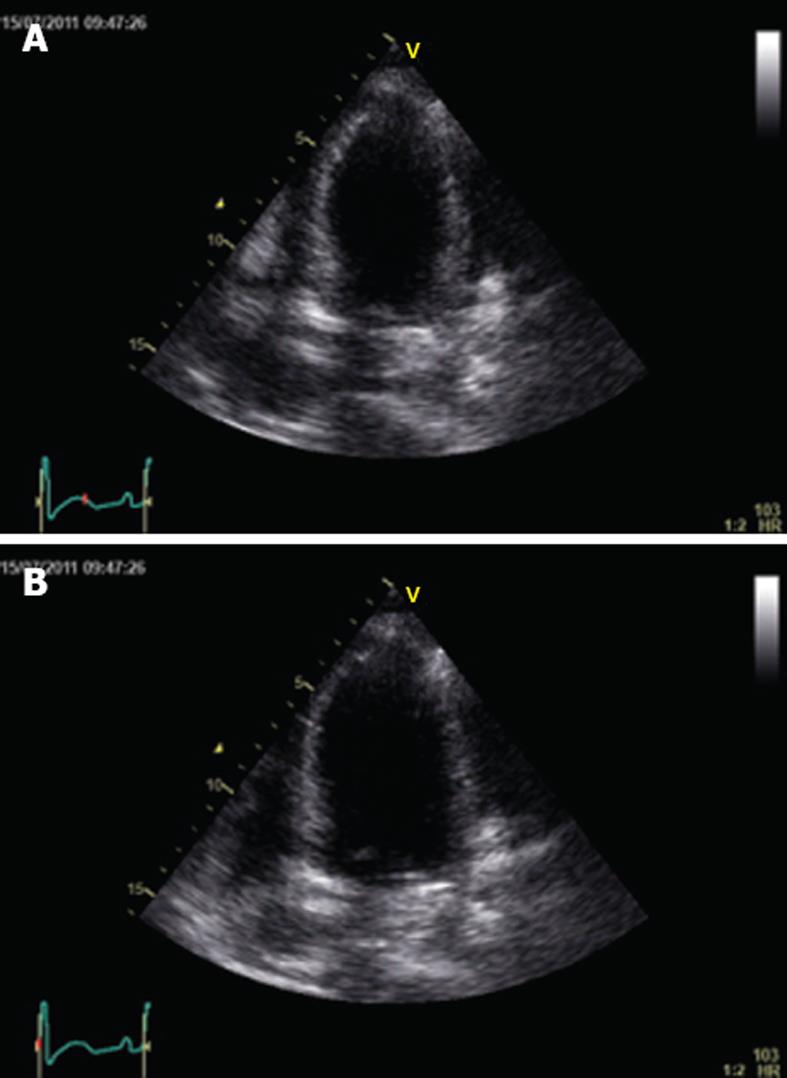

In the intensive care unit (ICU) she was intubated, treated with red blood cell and platelet transfusion and received norepinephrine; this treatment rapidly allowed an improvement in the patient’s hemodynamic and respiratory status. Twelve-lead ECG obtained soon after ICU admission showed sinus rhythm (90 beats/min) with diffuse T wave inversion and a markedly prolonged QT interval (QTc interval 523 ms) (Figure 1). Shortly after, an echocardiography was performed and showed reduced global left ventricular function with an ejection fraction of 32%, an impairment of contractility of all distal-apical segments, but sparing the base and midventricular regions, and mild mitral regurgitation (Figure 2A and B). Repeated measurements of cardiac injury markers 12 h later, showed a further increase in troponin I (13.49 ng/mL); thereafter, a rapid decrease in troponin I was observed and it normalized within 6 d.

Based on the patient’s history and age, and the absence of cardiovascular risk factors, we decided against performing urgent coronary angiography because of the occurrence of a sudden new rapid anemization due to hemoperitoneum requiring an urgent left ovariectomy.

She was successfully weaned off inotropic support 4 d later, and on day 6 she was successfully extubated.

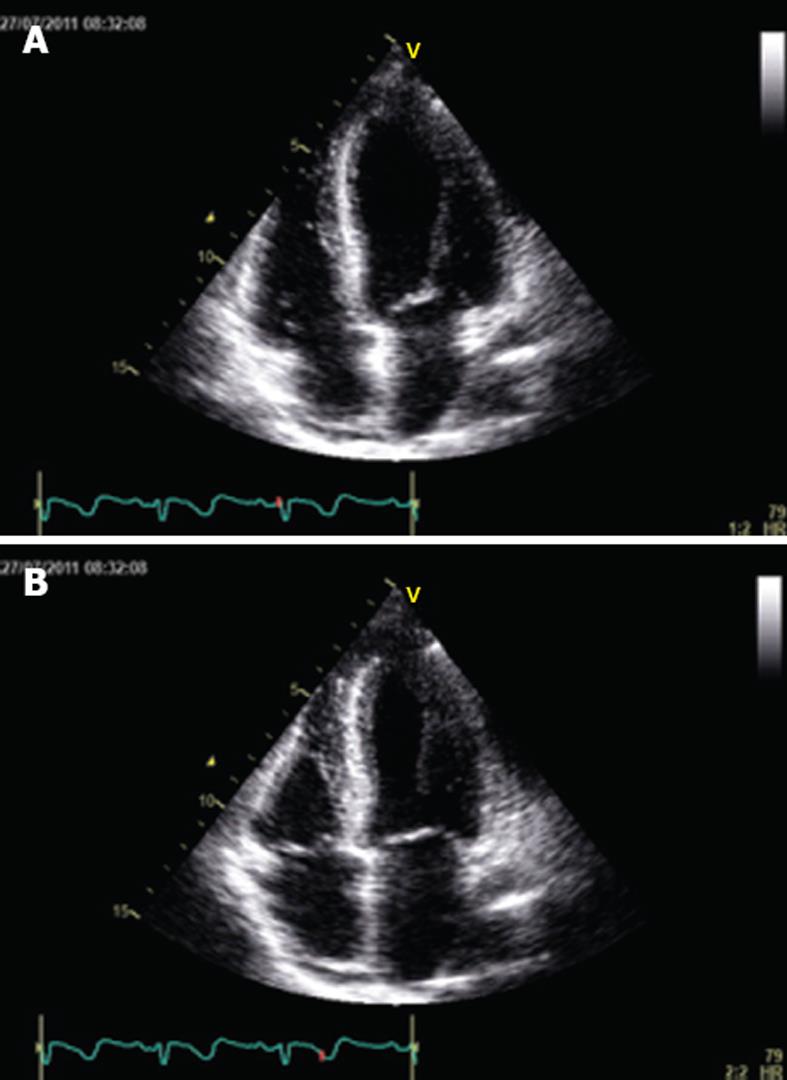

Serial ECG showed stable T wave inversion with a progressive normalization of QT interval and continuous ECG monitoring did not record further ventricular arrhythmias. After 7 d in the ICU, she was transferred to the postnatal ward in good overall condition. A repeat echocardiogram performed 3 wk later, revealed complete normalization of left ventricular function (Figure 3A and B). The patient was discharged on lisinopril 2.5 mg once a day and carvedilol 6.25 mg twice a day on the 24th post delivery day. One month later, the patient was completely asymptomatic and stress myocardial perfusion scintigraphy was normal.

Since the first description by Dote et al[9], an increasing number of reports of TCM have been published. The name TCM was given to this entity in the early 1990s of the last century because of the resemblance of the appearance of the left ventriculogram to the traditional Japanese octopus trap or takotsubo. It is a form of reversible cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction in both symptomatology and ECG findings, but without significant coronary artery disease on angiography[10].

The condition is typically seen in postmenopausal women, suggesting a protective effect of estrogens, but TCM in pregnant women has also been described in the peripartum period irrespective of mode of delivery[11,12]. Very recently, Zdanowicz et al[13] reported a case of a young woman undergoing elective cesarean section with apparent symptoms of acute coronary syndrome who was later diagnosed with TCM. The authors also performed a literature search on the occurrence of TCM in pregnancy; they identified 5 other published cases that occurred during elective cesarean delivery at term[6,7,14-16]. Patients’ age ranged from 30 to 42 years and only 2 had cardiovascular risk factors; in 4, the symptoms appeared intraoperatively, and in the remaining 2, symptoms did not appear until after surgery (1 h and a few hours postoperatively). All patients received either spinal or epidural anesthesia combined; this kind of anesthesia is generally perceived as a frightening procedure, especially as patients are awake during the entire process. The authors underlined the role of catecholamines/vasoconstrictive substances and possibly also of oxytocin and prostaglandins.

In our case a combination of extraordinary stress situations was present: a cesarean section performed in an awake patient after spinal anesthesia and oxytocin administration, and a very complicated immediate outcome with severe anemia and hemorrhagic shock which required hystero-ovariectomy.

Our patient presented another peculiarity: the initial manifestation was a cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. Although the electrocardiographic ST-T-wave changes that accompany the presentation of TCM are often associated with prolongation of the QT interval (as in our case), paradoxically ventricular arrhythmias are reported to be uncommon[17]. In a recent paper, Syed et al[18] reviewed all available series of TCM that reported on arrhythmia and reviewed a total 816 published cases; there were only 15 reported cases of ventricular fibrillation with a prevalence of 1.8%. It is currently unclear whether TCM is the cause or effect of arrhythmia; insight from magnetic resonance imaging has given an understanding of the evolution of TCM at a tissue level, characteristically with an absence of scar formation[19]. This suggested re-entry was an unlikely mechanism for arrhythmia and supported catecholaminergic, automatic, or fascicular tachycardias as more likely entities, with related cytosolic calcium overload[18]. In this setting, β-blockers may have a pivotal role, consistent with the finding of Dib et al[20] that suggested that pre-existing β-blocker administration may protect from ventricular arrhythmias.

The optimal duration of ECG monitoring in this condition is unclear, as is the risk or recurrent events after initial recovery. Currently there is insufficient data on which to recommend internal defibrillator use, which, at present, can only be considered on a case-by-case basis[18].

TCM is characterized by minor elevations in serum levels of cardiac enzymes which is usually not proportional to the initial left ventricular dysfunction. In our patient, a relevant increase in troponin I was recorded but this finding can be explained by the number of delivered shocks required to convert ventricular fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Based on the patient’s history and age, with the absence of cardiovascular risk factors, and based on the dramatic clinical course which required 2 surgical interventions because of life-threatening hemorrhagic shock, we could not conduct urgent coronary angiography; nevertheless, the psychological and physical stressful circumstances under which the symptoms appeared, the initial echocardiographic pattern which completely normalized after 3 wk and the absence of inducible myocardial ischemia on a treadmill test seemed to confirm the diagnosis of TCM.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates that TCM may occur in young women with no pre-existing cardiomyopathy and a complicated delivery, especially in combination with spinal anesthesia and oxytocin administration. Women with these characteristics may represent another vulnerable group for TCM; recognition of this disease is clinically important to avoid potentially lethal complications.

Peer reviewers: Akinori Kimura, MD, PhD, Department of Molecular Pathogenesis, Medical Research Institute, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, 1-5-45 Yushima, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8510, Japan; Konstantinos P Letsas, MD, PhD, FESC, Second Department of Cardiology, Laboratory of Invasive Cardiac Electrophysiology, Evangelismos General Hospital of Athens, 25, 28th Octovriou st., 15235 Athens, Greece; Brian Olshansky, MD, Professor of Medicine, Cardiac Electrophysiology, University of Iowa Hospitals, 200 Hawkins Drive, Room 4426a JCP, Iowa City, IA 52242, United States

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Kawai S, Kitabatake A, Tomoike H. Guidelines for diagnosis of takotsubo (ampulla) cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2007;71:990-992. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lyon AR, Rees PS, Prasad S, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE. Stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy--a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:22-29. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ueyama T, Kasamatsu K, Hano T, Yamamoto K, Tsuruo Y, Nishio I. Emotional stress induces transient left ventricular hypocontraction in the rat via activation of cardiac adrenoceptors: a possible animal model of 'tako-tsubo' cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2002;66:712-713. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, Wu KC, Rade JJ, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539-548. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, Maron MS, Lindberg J, Longe TF, Maron BJ. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:472-479. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Citro R, Pascotto M, Provenza G, Gregorio G, Bossone E. Transient left ventricular ballooning (tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy) soon after intravenous ergonovine injection following caesarean delivery. Int J Cardiol. 2010;138:e31-e34. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Crimi E, Baggish A, Leffert L, Pian-Smith MC, Januzzi JL, Jiang Y. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Acute reversible stress-induced cardiomyopathy associated with cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia. Circulation. 2008;117:3052-3053. [PubMed] |

| 8. | D'Amato N, Colonna P, Brindicci P, Campagna MG, Petrillo C, Cafarelli A, D'Agostino C. Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a pregnant woman. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:700-703. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dote K, Sato H, Tateishi H, Uchida T, Ishihara M. [Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasms: a review of 5 cases]. J Cardiol. 1991;21:203-214. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Nishioka K, Kono Y, Umemura T, Nakamura S. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;143:448-455. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Malinow AM, Butterworth JF, Johnson MD, Safon L, Rein M, Hartwell B, Datta S, Lind L, Ostheimer GW. Peripartum cardiomyopathy presenting at cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 1985;63:545-547. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Pearson GD, Veille JC, Rahimtoola S, Hsia J, Oakley CM, Hosenpud JD, Ansari A, Baughman KL. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review. JAMA. 2000;283:1183-1188. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zdanowicz JA, Utz AC, Bernasconi I, Geier S, Corti R, Beinder E. "Broken heart" after cesarean delivery. Case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:687-694. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Muller O, Roguelov C, Pascale P. A basal variant form of the transient 'midventricular' and 'apical' ballooning syndrome. QJM. 2007;100:738-739. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Parodi G, Antoniucci D. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome after inadvertent epidural administration of potassium chloride. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:e14-e15. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hawthorne L, Lyons G. Cardiac arrest complicating spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1997;6:126-129. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1523-1529. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Syed FF, Asirvatham SJ, Francis J. Arrhythmia occurrence with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a literature review. Europace. 2011;13:780-788. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Syed IS, Prasad A, Oh JK, Martinez MW, Feng D, Motiei A, Glockner JD, Breen JF, Julsrud PR. Apical ballooning syndrome or aborted acute myocardial infarction? Insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;24:875-882. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Dib C, Prasad A, Friedman PA, Ahmad E, Rihal CS, Hammill SC, Asirvatham SJ. Malignant arrhythmia in apical ballooning syndrome: risk factors and outcomes. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2008;8:182-192. [PubMed] |