Published online Apr 26, 2011. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v3.i4.117

Revised: April 4, 2011

Accepted: April 11, 2011

Published online: April 26, 2011

Uremic cardiomyopathy is chronic ischemic left ventricular dysfunction characterized by heart failure, myocardial ischemia, hypotension in dialysis and arrhythmia. This nosologic entity represents a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease receiving long-term hemodialysis. It is intuitive that revascularization in the presence of coronary artery disease in these patients represents an effective option for improving their prognosis. Although the surgical option seems to be followed by the best clinical outcome, some patients refuse this option and others are not good candidates for surgery. The present report describes the case of a patient affected by uremic cardiomyopathy and severe coronary artery disease in whom revascularization with percutaneous coronary angioplasty was followed by a significant improvement in quality of life.

- Citation: Petrillo G, Cirillo P, Prastaro M, D’Ascoli GL, Piscione F. Percutaneous approach to treatment of coronary disease in a patient with uremic cardiomyopathy. World J Cardiol 2011; 3(4): 117-120

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v3/i4/117.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v3.i4.117

Uremic cardiomyopathy is chronic ischemic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction characterized by heart failure (HF), myocardial ischemia, hypotension in dialysis and arrhythmia[1]. This nosologic entity represents a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease receiving long-term hemodialysis[1,2].

Revascularization in the presence of coronary artery disease in these fragile patients might represent an effective option in order to improve their poor prognosis. Although the surgical option seems to be followed by the best clinical outcome, some patients refuse this option and others are not good candidates for surgery. In these patients percutaneous approach may be a valid alternative. Treatment of uremic patients with ischemic LV dysfunction is nowadays still debated.

A 55-year-old male patient with a history of uremic cardiomyopathy was admitted to our Department because, during dialysis, severe hypotension associated with chest pain occurred. An electrocardiogram recorded during chest pain showed significant depression of the ST segment in the anterior leads. His clinical history was notable for several episodes of decompensated HF.

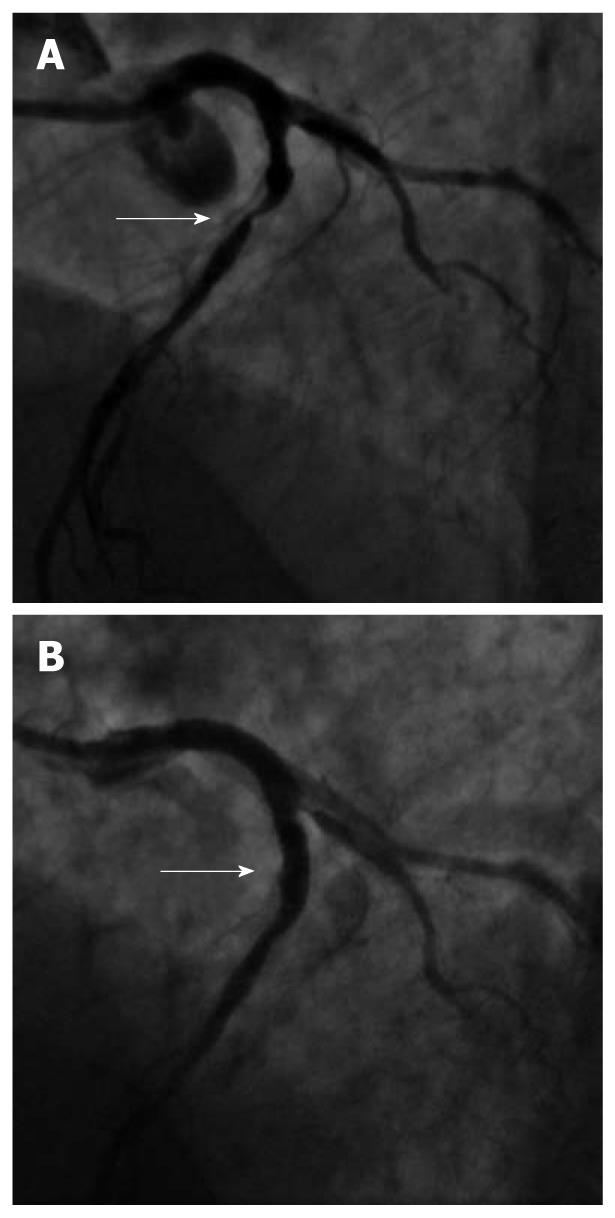

An echocardiogram showed severe reduction of LV ejection fraction (33%, biplane Simpson’s method) with akinesis of the apex, inferior wall and basal segment of the interventricular septum, hypokinesis of the lateral, anterior and postero-lateral walls and of the medium segment of the interventricular septum [wall motion score index (WMSI): 2.375]. In addition, a severe regurgitation of the mitral valve was reported. As this patient was suspected of having coronary artery disease, we decided to perform a coronary angiography. After placing a 6-French sheath in the right femoral artery, coronary angiography revealed atherosclerotic lesions of the 3 main coronary vessels. Specifically, he had a subocclusive calcific stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) (Figure 1A), and borderline stenosis in the medium segment of the circumflex coronary artery (CX) and of the distal right coronary artery (RCA).

After consultation with the cardiac surgeon, who suggested performing complete coronary revascularization of LAD, CX and RCA with coronary artery bypass surgery, the patient refused this treatment option. Thus, we decided to treat LAD by performing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as the best choice of revascularization.

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 500 mg iv, heparin (4500 IU iv), and a loading dose of 300 mg of clopidogrel were administered, after which the LAD lesion was treated with (PCI) and stenting resulting in a good angiographic result with TIMI 3 flow (Figure 1B). To reduce the risk of bleeding at the arterial puncture site, it was sealed with an Angio-Seal™ (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) vessel closure device. He was discharged on ASA 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d for 1 mo followed by ASA monotherapy (100 mg/d).

After discharge, the patient reported a significant improvement in his clinical status. Specifically, hypotension episodes or chest pain with electrocardiographic changes during dialysis did not occur again. Of note, the echocardiogram showed improvement of the ejection fraction (45%, biplane Simpson’s method) and of segmental wall motion (normal kinesis of the basal and medium segments of interventricular septum, lateral, anterior and postero-lateral walls. The apex became hypokinetic while akinesis of the inferior wall persisted; WMSI: 1.5). Moreover, an improvement in mitral valve regurgitation was reported (Table 1).

| Pre-PCI | Post-PCI | |

| LVIDd (mm) | 50 | 45 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 39 | 37 |

| LVIDs/BSA (mm/m2) | 35 | 32 |

| EFS (%) | 22 | 18 |

| EF, Simpson Biplane (%) | 33 | 45 |

| LA volume/BSA (mL/m2) | 42 | 23 |

At 1-year follow-up, the patient had no cardiovascular events and showed no instrumental or clinical signs of ischemia. Of note, in his “new” clinical history he did not display any episodes of decompensated HF.

In the present report we describe the case of a patient affected by uremic cardiomyopathy and with angiographic evidence of coronary disease involving more than one vessel in which the clinical outcome was significantly improved by revascularization obtained by PCI.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among patients with end-stage renal disease receiving long-term hemodialysis[1]. HF is one of the most frequent cardiac complications in this type of patient and is associated strongly with a poor prognosis[2]. The pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients is characterized by disorders of perfusion (coronary artery disease, CAD) and disorders of structure and function (LV hypertrophy with subsequent dysfunction)[3]. Specifically, one-third of patients beginning dialysis has a history of symptomatic CAD and congestive HF[4]. Noteworthy, a close relationship exists between these 2 clinical entities because the clinical impact of CAD is mediated through changes in LV function. In this clinical setting, this specific type of chronic ischemic LV dysfunction is known as uremic cardiomyopathy.

Treatment of high risk patients, such as uremic patients, with ischemic LV dysfunction has been strongly debated. The benefits of pharmacologic management are strongly evidence-based, and all patients should be placed on medical management with recommended agents according to the 2005 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guidelines Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure[5]. On the contrary, clinicians have challenged with decisions about the unclear benefits of revascularization in these high-risk patients.

Percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting is the most widespread revascularization method for coronary disease which can be safely performed also in patients with low LV ejection fraction obtaining, in addition, acceptable late major adverse cardiac event rates[6]. The ACC/AHA guidelines provide several recommendations on the role of coronary angiography. A class I recommendation is given to patients presenting with chronic HF and angina or significant ischemia[5]. Coronary angiography is a class IIa recommendation in patients with HF who have chest pain that may or may not be of cardiac origin, whose coronary anatomy is unknown. Moreover, in spite of the concerns in the guidelines about the effectiveness of revascularization, coronary angiography is also a class IIa recommendation in patients with HF and known or suspected CAD but who do not have angina. In practice, if not previously performed, cardiac catheterization is reasonable in all patients who present with HF and are potential candidates for revascularization. In addition, when perfusion deficits and segmental wall-motion abnormalities identified on noninvasive testing cannot reliably distinguish patients with ischemic LV dysfunction from those with nonischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary angiography is usually required to reliably demonstrate or exclude the presence of CAD.

Coronary angiography plays an important role not only in determining which patient with HF is a candidate for revascularization but also to make decisions about the appropriate medical therapy. Use of aspirin is not recommended in patients without obstructive coronary disease and HF except for other indications. In contrast, patients with CAD should be treated with vasculoprotective medications including therapy with statins.

The 2005 ACC/AHA guidelines also provide recommendations for revascularization[5]. Revascularization in patients who have HF symptoms and angina pectoris is a class I recommendation. Despite theoretical arguments that support revascularization, the benefit is unproven in patients with HF but no angina.

The 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) paid attention to patients with poor LV function, and specifically considered the number of vessels responsible for CAD. These guidelines assigned a class I recommendation for patients with LV dysfunction and left main, left main equivalent, and proximal LAD CAD with 2- or 3-vessel disease without regard to symptoms or viability[7]. A class IIa recommendation was given to patients with LV dysfunction with a myocardium that could be significantly revascularized without the class I anatomical patterns, but again, without regard to symptoms. The last version of the guidelines for PCI did not contain any recommendation for patients with clinical HF or LV dysfunction[8]. In practice, HF patients with ischemic dysfunction and angina are considered as potential PCI candidates if revascularization is feasible.

In this complex dispute between surgery and percutaneous intervention in patients receiving dialysis, a recent meta-analysis has pointed out that short-term mortality was higher after CABG compared with that after PCI. However, the PCI mortality rate significantly increased after the first year following the procedure, finally cancelling any difference between the 2 kinds of treatment[9]. More recently, Sunagawa et al[10] have reported that CABG is superior to PCI in patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis in terms of long-term outcomes for cardiac death, major adverse cardiac events, and target lesion revascularization.

In conclusion, patients with uremic cardiomyopathy are characterized by clinical complexity and, in addition, they often present CAD involving more than one vessel. Thus, surgery appears as the best treatment especially when chronic LV dysfunction is associated with CAD. However, this treatment could not always have been applied: some patients are too critical to be surgically treated and some others refuse this option. Anyway, these patients need revascularization. Here, we point out that the percutaneous approach may be considered as a valid alternative to surgery, with the ability to significantly improve the patient’s quality of life.

Peer reviewers: Masamichi Takano, MD, PhD, Cardiovascular Center, Chiba-Hokusoh Hospital, Nippon Medical School, 1715 Kamakari, Imba, Chiba, 270-1694, Japan; Seung-Woon Rha, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA, FESC, FSCAI, FAPSIC, Cardiovascular Center, Korea University Guro Hospital, 80, Guro-dong, Guro-gu, Seoul, 152-703, South Korea

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, Chavers B, Gilbertson D, Ishani A, Kasiske B, Liu J, Mau LW, McBean M. United States Renal Data System 2008 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:S1-S374. |

| 2. | Bruch C, Rothenburger M, Gotzmann M, Wichter T, Scheld HH, Breithardt G, Gradaus R. Chronic kidney disease in patients with chronic heart failure--impact on intracardiac conduction, diastolic function and prognosis. Int J Cardiol. 2007;118:375-380. |

| 3. | Drüeke TB, Massy ZA. Atherosclerosis in CKD: differences from the general population. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:723-735. |

| 4. | Parfrey PS, Foley RN, Harnett JD, Kent GM, Murray DC, Barre PE. Outcome and risk factors for left ventricular disorders in chronic uraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1277-1285. |

| 5. | Hunt SA. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:e1-82. |

| 6. | Di Sciascio G, Patti G, D'Ambrosio A, Nusca A. Coronary stenting in patients with depressed left ventricular function: acute and long-term results in a selected population. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;59:429-433. |

| 7. | Eagle KA, Guyton RA, Davidoff R, Edwards FH, Ewy GA, Gardner TJ, Hart JC, Herrmann HC, Hillis LD, Hutter AM Jr. ACC/AHA 2004 guideline update for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1999 Guidelines for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery). Circulation. 2004;110:1168-1176. |

| 8. | Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC Jr, King SB 3rd, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE Jr. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2205-2241. |

| 9. | Nevis IF, Mathew A, Novick RJ, Parikh CR, Devereaux PJ, Natarajan MK, Iansavichus AV, Cuerden MS, Garg AX. Optimal method of coronary revascularization in patients receiving dialysis: systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:369-378. |

| 10. | Sunagawa G, Komiya T, Tamura N, Sakaguchi G, Kobayashi T, Murashita T. Coronary artery bypass surgery is superior to percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents for patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1896-1900; discussion 1900. |