Published online Oct 26, 2011. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v3.i10.337

Revised: August 20, 2011

Accepted: August 27, 2011

Published online: October 26, 2011

Accelerated epicardial coronary artery atherosclerosis has been well-documented in cocaine users. There are only two reported cases of cocaine-associated diffuse intimal expansion by proliferated smooth muscle cells causing significant coronary luminal compromise. This type of lesion histologically resembled chronic transplant arteriopathy. Here, we report a third such case.

- Citation: Bhavsar T, Hayes T, Wurzel J. Epicardial coronary artery intimal smooth muscle hyperplasia in a cocaine user. World J Cardiol 2011; 3(10): 337-338

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v3/i10/337.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v3.i10.337

In cocaine users, thickening of small intramyocardial arteries, coronary artery dissection and accelerated coronary atherosclerosis have been previously reported[1]. Cocaine-associated epicardial coronary artery intimal expansion due to smooth muscle hyperplasia, histologically resembling that seen in chronic transplant vasculopathy, has only been reported twice[2,3]. We now report the third such case.

A 22-year-old man was seen collapsing at home after having ingested codeine containing syrup and other unspecified drugs. Emergency medical personnel found pulseless electrical activity, performed successful resuscitation, and brought the patient to the Emergency Department (ED) of an affiliated hospital. History included obesity, sleep apnea, 10 to 15 pack-years of cigarette smoking, and admission for a psychotic episode after having smoked illy (also known as wet or fry). Illy is marijuana treated with embalming fluid (formaldehyde and methanol), usually containing phencyclidine[4]. In addition to the aforementioned drugs, there was a history of alcohol, heroin, and codeine use. In the ED, ventricular fibrillation occurred; defibrillation was successful, but consciousness was never regained during the hospitalization. A urine screen showed cocaine (> 300 ng/mL), opiates (> 2000 ng/mL), and PCP (> 25 ng/mL). The blood alcohol was 8.5 mg/dL. In addition to the loss of consciousness, ventilator-dependent respiratory failure, rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, elevated cardiac troponin, bacteremia and brain death marked the hospital course. With agreement of the family, mechanical ventilation was discontinued on the tenth hospitalization day and death occurred about 10 min later.

Autopsy findings confirmed the clinical history. The heart weighted 500 g. The left anterior descending and a diagonal branch, left circumflex, and right and posterior descending coronary arteries showed diffuse, concentric luminal narrowing almost throughout. The sectioned myocardium showed a focus of pallor involving the base of the heart in the posterior interventricular septum measuring 1.2 cm × 1.3 cm × 3 cm. A small focus of pallor was also present in the left ventricular posterior papillary muscle.

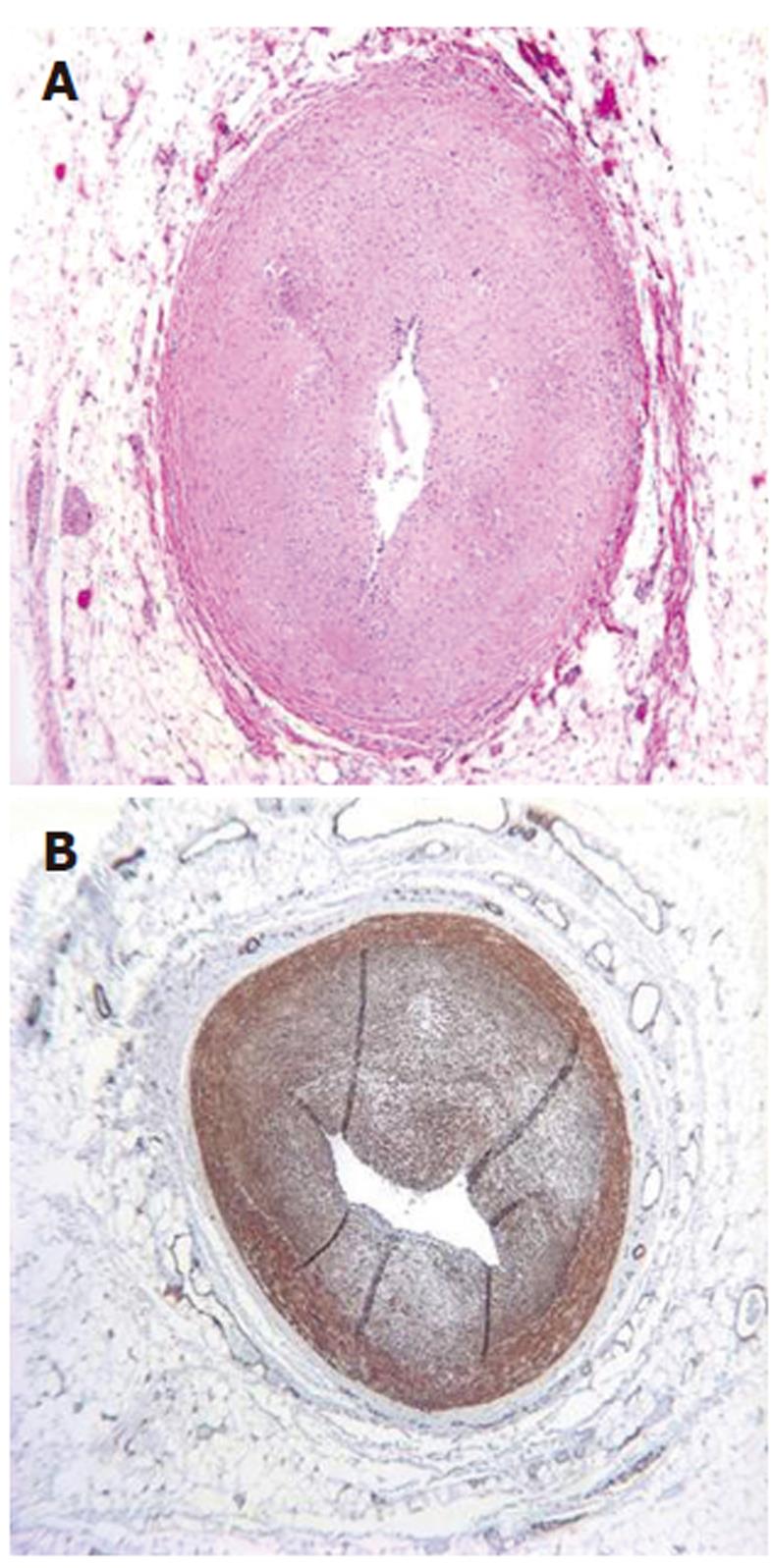

Histologic examination of the coronary arteries showed stenoses of 50% to 90% in different sections from the affected vessels (Figure 1A). Intimal expansion by smooth muscle-actin expressing cells and extracellular matrix caused luminal compromise (Figure 1B). Lipid containing atheromas, recanalized thrombi and calcification were rare. Atherosclerosis was imperceptible in other mid-sized arteries and was only minimal in the large elastic arteries. Histologic sections from the myocardium showed infarcts of varying appearance. The posterior septal sections showed healed infarction. Both left ventricular papillary muscles had foci of necrotic myocytes, minimal fibrosis, and no inflammation. The right ventricle contained a microscopic focus of contraction band necrosis without inflammation.

Other autopsy findings included acute and organizing pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, acute tubular necrosis, diffuse softening of the brain numerous in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, brainstem and cerebellum.

Direct acute effects of cocaine or PCP on the myocardium, the structural coronary, myocardial lesions described above or any combination of these could have caused death.

Morphologic effects of cocaine on the epicardial coronary arteries have been documented previously and included dissection and atherosclerosis[1].

Cocaine-related non-atherosclerotic intimal smooth-muscle cell proliferation resembling that seen in chronic vasculopathy has been reported in only two cases[2,3]. Our patient, as well as one other patient previously reported[2], used several drugs. Cocaine was considered to be the cause of the coronary lesions, although the possibility that some other agent was involved was not excluded, especially in light of the few reported cases. We have also seen similar lesions in the small mesenteric arterial branches causing bowel infarction in another cocaine user; in this case the coronary arteries were not affected[5].

The mechanism by which cocaine might induce intimal smooth muscle hyperplasia in middle-sized arteries has not been elucidated. Recent findings, however, have suggested that smooth muscle proliferation could be the result of cocaine-induced expression of platelet derived growth factor[6]. Of course, the experimental model, human immunodeficiency virus infected mouse brain endothelial cells differs substantially from the human clinical situation.

In conclusion, we have described the third case of clinically significant non-atherosclerotic intimal smooth muscle hyperplasia in a cocaine user.

Peer reviewers: Rajesh Sachdeva, MD, FACC, FSCAI, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Associate Program Director, Interventional Cardiology Fellowship Program, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Director, Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, 4301 W. Markham street, #532, Little Rock, AR 72205, United States; Cristina Vassalle, PhD, G. Monasterio Foundation and Institute of Clinical Physiology, Via Moruzzi 1, I-56124 Pisa, Italy

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Karch SB. Cocaine cardiovascular toxicity. South Med J. 2005;98:794-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Simpson RW, Edwards WD. Pathogenesis of cocaine-induced ischemic heart disease. Autopsy findings in a 21-year-old man. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:479-484. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pamplona D, Gutierrez PS, Mansur AJ, César LA. [Fatal acute myocardial infarction in a young cocaine addict]. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1990;55:125-127. [PubMed] |

| 4. | D'Onofrio G, McCausland JB, Tarabar AF, Degutis LC. Illy: clinical and public health implications of a street drug. Subst Abus. 2006;27:45-51. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bhavsar T, Hayes T, Wurzel J. Intimal smooth muscle proliferation of mesenteric arterial branches complicated by fatal ischemic enterocolitis in a cocaine user. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1309. |

| 6. | Yao H, Duan M, Buch S. Cocaine-mediated induction of platelet-derived growth factor: implication for increased vascular permeability. Blood. 2011;117:2538-2547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |