Published online Jul 26, 2010. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i7.211

Revised: June 30, 2010

Accepted: July 7, 2010

Published online: July 26, 2010

Acute total or subtotal occlusion of left main coronary artery (LMCA) is a catastrophic and mostly fatal event. Patients may present with cardiogenic shock and die whenever this event occurs. Survival is strongly dependent on the presence of collateral blood flow to the left coronary artery or a dominant right coronary artery, and emergency intervention for preserving the left ventricular function. Here, we present a case of a 14-year-old boy with subtotal occlusion of the LMCA accompanying acute myocardial infarction probably caused by congenital syphilis according to his positive serum syphilis antibody. His survival was closely associated with a dominant right coronary artery and timely thrombolytic therapy. Finally, he was treated with angioplasty and paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation. He was followed up after stenting and was doing quite well at the time when we wrote this paper.

- Citation: Li JJ, Xu B, Chen JL. Stenting for left main coronary artery occlusion in adolescent: A case report. World J Cardiol 2010; 2(7): 211-214

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v2/i7/211.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v2.i7.211

Acute total or subtotal occlusion of left main coronary artery (LMCA) is an emergency condition and a catastrophic event. Almost all such patients would die before their admission to a hospital. It was reported that the hospital mortality of patients with acute occlusion of LMCA is around 50%[1]. However, the recanalization time is a critical point affecting the mortality of patients. It has been shown that the time from onset of the disease to the recanalization is quite short in patients with a higher survival rate[2,3]. Additionally, several factors are apparently involved in survivors suffering from acute total or subtotal occlusion of LMCA, including the presence of collateral blood flow to the left coronary artery or a dominant right coronary artery, or rapid revascularization[4,5]. In this condition, the left ventricular function can be preserved once the event occurs[4,5].

Cardiovascular abnormalities are well-known manifestations of tertiary syphilis infection, including syphilitic coronary artery ostial stenosis[6]. We here present a rare case of a 14-year-old boy with acute subtotal occlusion of LMCA accompanying acute myocardial infarction probably caused by congenital syphilis. He was successfully treated with thrombolytic therapy, angioplasty, and drug-eluting stent implantation.

On June 5, 2005, a 14-year-old boy was transferred to our hospital due to acute myocardial infarction. At admission, he complained of only uncomfortable chest. In the afternoon of May 29, 2005, he played football and then developed severe back and substernal chest pain accompanying syncope after his game. He was admitted to the emergency department of a local hospital where he had an episode of ventricular fibrillation. Electrocardiogram demonstrated an elevated ST segment in leads V1-V6. Although the patient had transient hypotension and pulmonary edema after attack of the disease, he survived after intravenously thrombolytic therapy with urokinase. The patient had no history of known heart disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes or cigarette smoking, or a known family history of coronary artery disease. Physical examination showed no pathological signs. Laboratory tests were normal except for positive serum syphilis antibody.

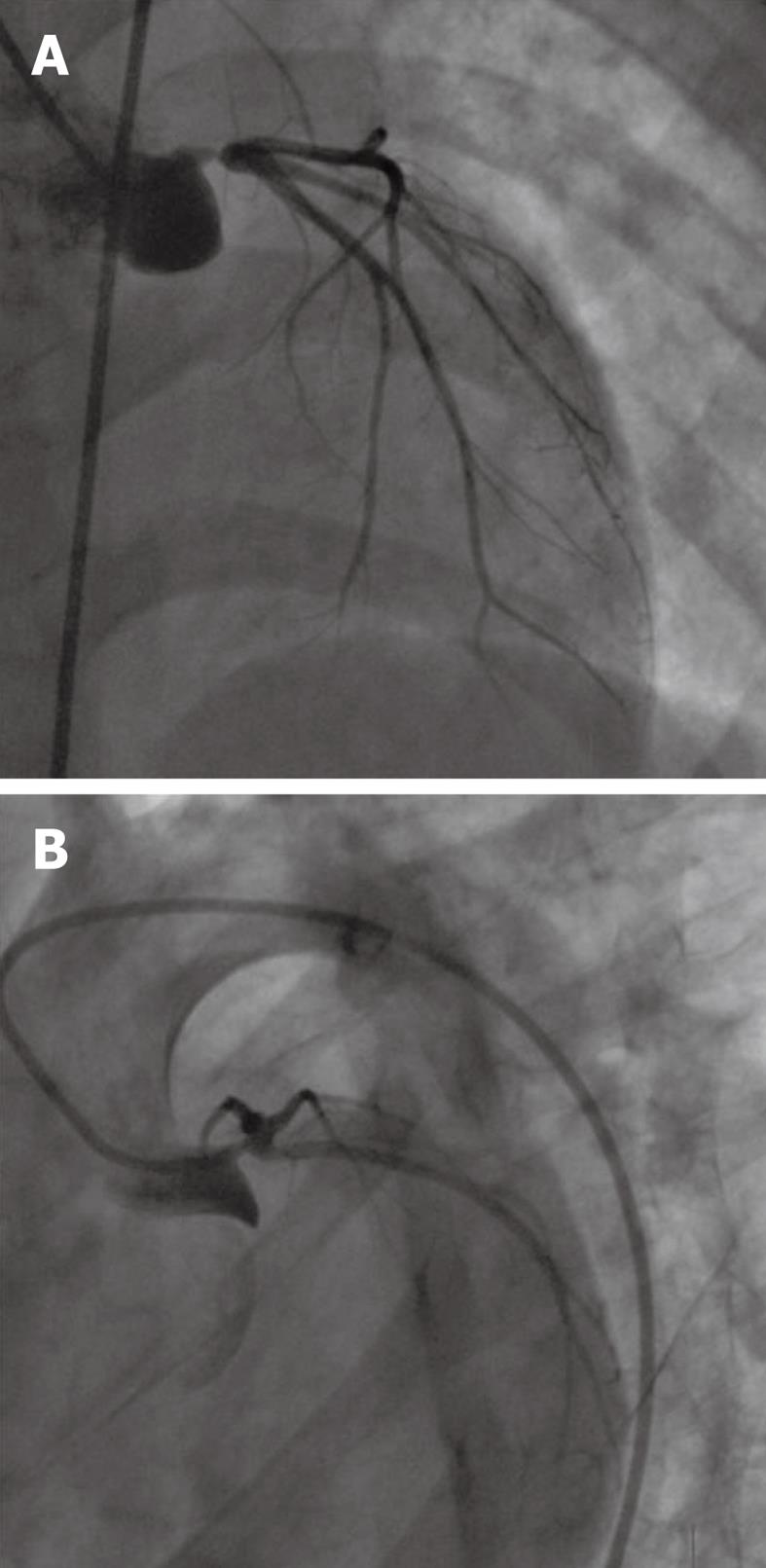

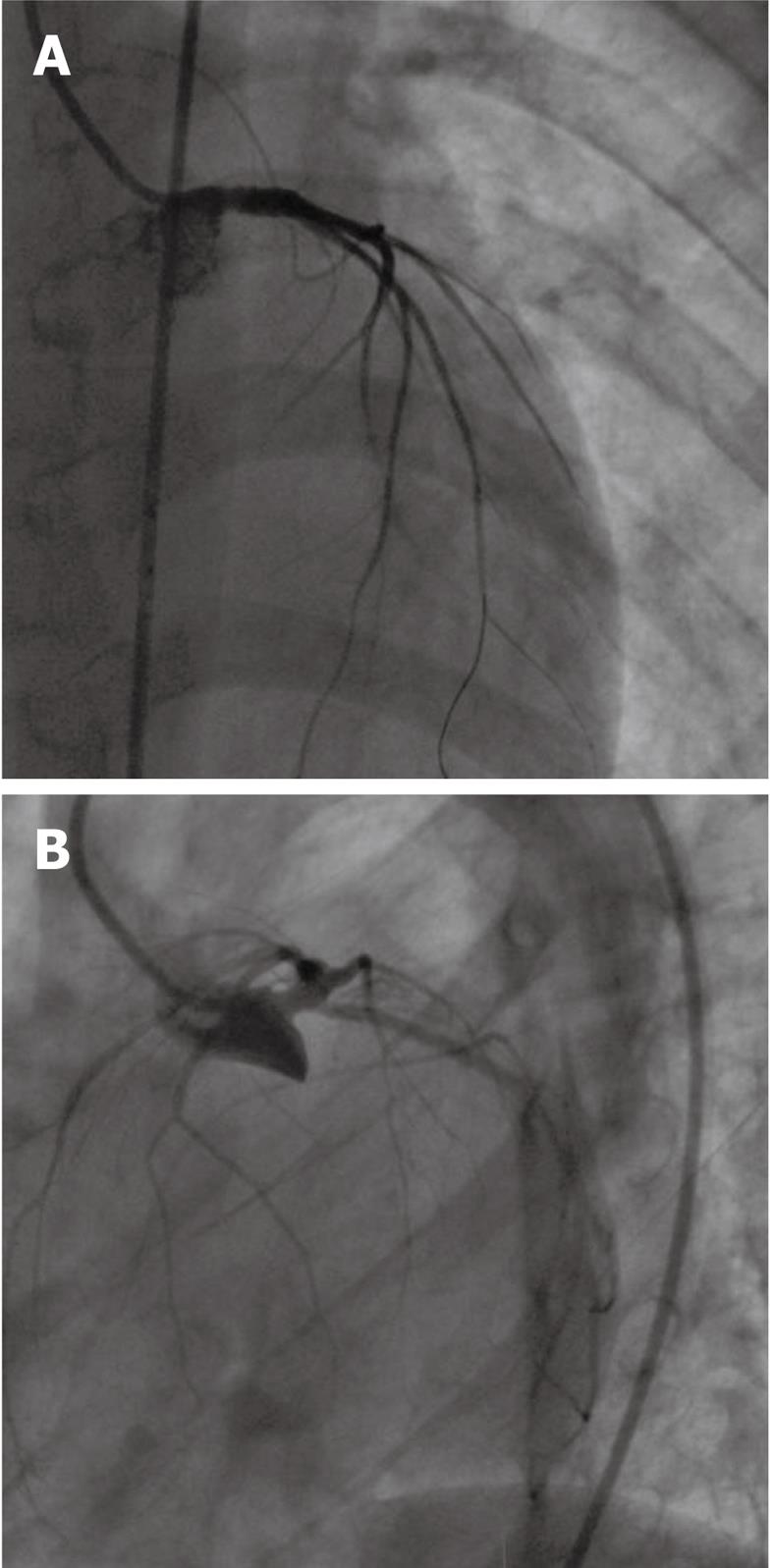

Selective coronary angiography was performed for him on June 7, 2005, showing a dominant right coronary artery and a subtotal occlusion (approximately 99%) of the distal LMCA, but no other obvious angiographic evidence for coronary atherosclerosis (Figure 1A and B). No right-to left coronary artery collateral was observed. Therefore, a 3.5 mm × 12 mm paclitaxel-eluting stent (Bosten Scientific Corporation, Natick, Massachusetts, USA) was implanted cross the proximal of the left anterior descending artery to the ostial of LMCA for the patient (Figure 2A and B). The patient was followed up for 12 and 24 mo after stent implantation, and he was doing quite well at the time when we wrote this paper.

Total or subtotal occlusion of LMCA is an uncommon event at cardiac catheterization due to its lethal nature. Since the left coronary system supplies blood for most of the left ventricular myocardium, acute total occlusion of left coronary system in the absence of collateral circulation leads to cardiogenic shock, which is usually fatal[1]. The prevalence of total occlusion of LMCA in patients undergoing coronary angiography is very low (0.04%-0.06%) and extremely rare in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)[3].

Survival, although uncommon, after total or subtotal occlusion of LMCA, is linked to a large and dominant right coronary artery, even if no collateral has been identified at angiography. It has been reported that survival after occlusion of LMCA is dependent on the severity of occlusion and development of right-to-left collateral blood flow[1]. The mortality is higher in patients with occlusion of LMCA even in hospital regardless of age. In our case, subtotal occlusion of LMCA was diagnosed by angiography and history of acute myocardial infarction. Apparently, his survival was associated with a dominant right coronary artery and subsequent thrombolytic therapy.

Total or subtotal occlusion of LMCA in elderly patients is usually due to atherosclerotic plaque rupture and not uncommon[7]. However, LMCA occlusion in a young patient may be associated with embolization, hyper-coagulability, arteritis, spasm, spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Yamasa et al[8] have reported a case of myocardial infarction secondary to thrombus in LMCA. Their patient had a past medical history of splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Khan et al[9] have also reported a healthy young male case of huge thrombus in LMCA, who survived after heart transplantation. Bush et al[10] have recently described ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction involving the LMCA in a middle-aged man who was treated with primary angioplasty in combination with implantation of sirolimus-eluting stents. Cases of acute myocardial infarction due to blunt chest trauma are also available[11]. Our case of acute myocardial infarction was treated with thrombolytic therapy, and subsequently coronary stenting for LMCA.

Cardiovascular involvement is a rare complication of congenital syphilis, and syphilis diagnosed at any stage should be immediately treated with appropriate antibiotics, preferably penicillin[6]. The occlusion of LMCA in our patient might be due to congenital syphilis according to his positive serum syphilis antibody, and subsequently thrombotic formation triggered by strenuous exercise. The mechanism underlying thrombotic formation in our patient is unclear, but may be associated with hypercoagulability or spasm due to arteritis. Kennedy et al[6] have reported a case of a 32-year-old female who died of myocardial infarction due to coronary artery ostial stenosis secondary to syphilitic aortitis. In our patient, no evidence of either dissection flap or severe chest blow was found on coronary angiography. Laboratory tests were negative except for positive serum syphilis antibody, indicating that “congenital syphilis” may be a reasonable cause of left main coronary orifice stenosis. However, atheroslerotic origin could not be absolutely excluded.

It has been shown that fatty streaks appearing in aorta of most children over 3 years of age are increased in adolescence with coronary arteries involved approximately a decade later[12,13]. Evidence of coronary atherosclerosis (ranging from insignificant disease to total or subtotal occlusion) in young individuals has also been demonstrated in autopsy studies[12]. The prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis was 77% in the Korean War (mean age 22.1 and 20.5 years) and 45% in the Vietnam War (mean age 22.1 years)[14,15]. During the Vietnam War, severe coronary atherosclerosis occurred in about 5% of all cases[15]. It has been recently reported that coronary atherosclerosis can also occur in young trauma patients (age < 35 years, mean age 25.6 years)[15]. The prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in this study is consistent with that in the Korean War[14]. Signs of coronary atherosclerosis have been found in 78.3% of patients with over 50% narrowing observed in 20.7% of them. Lesions producing over 75% narrowing have been observed in 9% of the patients. LMCA or significantly diseased 2- or 3-vessels can be found in 20% of the patients[16]. The proximal segment of the left anterior descending and circumflex arteries appears to be involved more often than that of the distal vessels. Major risk factors are smoking and family history of coronary heart disease. Although coronary atherosclerosis in young individuals has been well documented, coronary atherosclerosis was not detectable in this patient.

The therapeutic strategies for total or subtotal occlusion of LMCA include thrombolytic therapy, PCI, and emergency coronary artery bypass grafting. Drug-eluting stent has been widely used for stenosis or total/subtotal occlusion of LMCA. Bush et al[10] have reported a case of a middle-age man with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction involving LMCA, who was successfully treated with primary angioplasty and sirolimus-eluting stenting, suggesting that PCI is a promising procedure for acute total or subtotal occlusion of LMCA.

Peer reviewers: Paul Vermeersch, MD, Antwerp Cardiovascular Institute Middelheim, AZ Middelheim, Lindendreef 1, B-2020 Antwerp, Belgium; Giuseppe Biondi- Zoccai, MD, Division of Cardiology, University of Turin, Corso Bramante 88-90, 10126 Turin, Italy

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Goldberg S, Grossman W, Markis JE, Cohen MV, Baltaxe HA, Levin DC. Total occlusion of the left main coronary artery. A clinical, hemodynamic and angiographic profile. Am J Med. 1978;64:3-8. |

| 2. | de Feyter PJ, Serruys PW. Thrombolysis of acute total occlusion of the left main coronary artery in evolving myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:1727-1728. |

| 3. | Shahian DM, Butterly JR, Malacoff RF. Total obstruction of the left main coronary artery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46:317-320. |

| 4. | Shigemitsu O, Hadama T, Miyamoto S, Anai H, Sako H, Iwata E. Acute myocardial infarction due to left main coronary artery occlusion. Therapeutic strategy. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50:146-151. |

| 5. | Spiecker M, Erbel R, Rupprecht HJ, Meyer J. Emergency angioplasty of totally occluded left main coronary artery in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina pectoris--institutional experience and literature review. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:602-607. |

| 6. | Kennedy JL, Barnard JJ, Prahlow JA. Syphilitic coronary artery ostial stenosis resulting in acute myocardial infarction and death. Cardiology. 2006;105:25-29. |

| 7. | Huńka I, Snopek G, Czubalska M, Bielecki D, Drewniak W, Dabrowski M. [Left main coronary artery stenting in a ninety year old female with recurrent acute coronary syndrome -- a case report]. Kardiol Pol. 2005;63:328-330. |

| 8. | Yamasa T, Hata S, Fukae A, Ninomiya A, Ikeda S, Miyahara Y, Kohno S. Successful removal of a left main coronary artery thrombus induced by vasospasm to the aorta [correction of vasospasm of the aorta] after the injection of contrast medium. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:579-580. |

| 9. | Khan NUA, Movahed A, Saha PK, Raza JA, Golzar J, Williams JM, Shammas RL. Left main myocardial infarction in a healthy young male-a case report. Int J Angiol. 2005;14:94-96. |

| 10. | Bush HS, Strong DE, Novaro GM. Successful use of sirolimus-eluting stents for treatment of ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction caused by left main coronary artery occlusion. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:421-423. |

| 11. | Sinha AK, Agrawal RK, Singh A, Kumar R, Kumar S, Sinha A, Saurabh , Kumar A. Acute myocardial infarction due to blunt chest trauma. Indian Heart J. 2002;54:713-714. |

| 12. | Strong JP. Landmark perspective: Coronary atherosclerosis in soldiers. A clue to the natural history of atherosclerosis in the young. JAMA. 1986;256:2863-2866. |

| 13. | Tuzcu EM, Kapadia SR, Tutar E, Ziada KM, Hobbs RE, McCarthy PM, Young JB, Nissen SE. High prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic teenagers and young adults: evidence from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 2001;103:2705-2710. |

| 14. | Enos WF Jr, Beyer JC, Holmes RH. Pathogenesis of coronary disease in American soldiers killed in Korea. JAMA. 1955;158:912-914. |

| 15. | McNamara JJ, Molot MA, Stremple JF, Cutting RT. Coronary artery disease in combat casualties in Vietnam. JAMA. 1971;216:1185-1187. |

| 16. | Joseph A, Ackerman D, Talley JD, Johnstone J, Kupersmith J. Manifestations of coronary atherosclerosis in young trauma victims--an autopsy study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:459-467. |

| 17. | Coats AJ. Ethical authorship and publishing. Int J Cardiol. 2009;131:149-150. |