Published online Dec 26, 2010. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i12.437

Revised: September 10, 2010

Accepted: September 17, 2010

Published online: December 26, 2010

AIM: To study recent experience and safety of ergonovine stress echocardiography in our centre.

METHODS: In this study we collected the clinical variables of patients referred since 2002 for ergonovine stress echocardiography, in addition to indications, the results of this test, complications, blood pressure and heart rate values during the test and the number and results of tests requested before this technique.

RESULTS: We performed 40 tests in 38 patients, 2 tests were carried out to verify therapy efficacy. The prevalence of classic cardiovascular risk factors was low and the most frequent indication was chest pain (57.5%). Coronary angiography was performed in 32 patients, and showed normal coronary arteries in 27 patients and non-significant stenosis in 5 cases. In 16 patients, coronary angiography was carried out after a positive or inconclusive ischemia test. Another 6 patients had a normal stress test (5 exercise electrocardiography tests and 1 nuclear imaging test). Of the 40 ergonovine stress echocardiography tests, 6 were positive (4 in the right coronary artery territory and 2 in the circumflex coronary artery territory), all of them by echocardiographic criteria, and by electrocardiographic criteria in only 3 (50%). The presence of non-significant coronary artery stenosis was more frequent in patients with positive ergonovine stress echocardiography (50% vs 6%, P = 0.038), and were related to ischemic territory. During the maximum stress stage, there was a higher systolic (130.26 ± 19.17 mmHg vs 136.58 ± 27.27 mmHg, 95% CI: -12.77 to 0.14 mmHg, P = 0.055) and diastolic blood pressure (77.89 ± 13.49 mmHg vs 83.95 ± 15.73 mmHg, 95% CI: -10.41 to -1.69 mmHg, P = 0.008) than at the baseline stage, and the same was registered with heart rate (73 ± 10.96 beats/min vs 79.79 ± 11.72 beats/min, 95% CI: -9.46 to -4.11 beats/min, P < 0.01). Nevertheless, there were only 2 hypertensive reactions during the last stage, which did not force a premature end to the test, without sustained tachy or bradyarrhythmias, and the technique was well tolerated in 58% of cases. A unique complication (2.5%) of this test was a prolonged vasospasm with a slight increase in necrosis biomarkers, however, this was without repercussion.

CONCLUSION: Ergonovine stress echocardiography can be performed with safety, is well tolerated in the majority of cases, and is useful for determining the ischemia mechanism in selected cases.

- Citation: Cortell A, Marcos-Alberca P, Almería C, Rodrigo JL, Pérez-Isla L, Macaya C, Zamorano JL. Ergonovine stress echocardiography: Recent experience and safety in our centre. World J Cardiol 2010; 2(12): 437-442

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v2/i12/437.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v2.i12.437

Coronary vasospasm may be the cause of effort angina, myocardial infarction, syncope and sudden death[1-3]. When there is no documentation of the initial clinical picture, the unique tests available for diagnosis orientation are the vasospasm provocation techniques.

There are several substances that can be used to cause a coronary vasospasm. Methylergometrine (a synthetic medicine chemically related to ergonovine) and acetylcholine are the most commonly used; another substances which can provoke vasospasm are histamine, dopamine and serotonin[4,5].

There is a significant demand for non-invasive tests in Cardiology for the assessment of ischemia due to fixed coronary stenosis. The situation in vasospasm provocation techniques is different, because their safety have been questioned[6]. However, there are a number of studies which have demonstrated that ergonovine stress echocardiography is a safe tool for the diagnosis of vasospasm, after confirming the absence of inducible ischemia or significant coronary stenosis by coronary angiography, and has many advantages compared with invasive provocation tests. These techniques have relevancy, especially, in the differential diagnosis of resting chest pain, which is suspected to be related to the vasospastic origin, in which coronary angiography or coronary computed tomography do not show significant stenosis[7-17].

In this study, we assessed the experience related to ergonovine stress echocardiography over the last few years in our centre, collected the clinical variables of patients referred to our laboratory and the test results.

We retrospectively collected the results of ergonovine stress echocardiography carried out in our centre since 2002. The tests were performed with the administration protocol of an intravenous bolus of ergonovine (methylergometrine) every 5 min across 3 stages (initial dose of 0.05 mg, middle dose of 0.10 mg and later dose of 0.20 mg), with blood pressure measurement and 12-lead electrocardiography at each stage and continuous echocardiography and electrocardiography (1-lead) monitoring. The criteria for finishing the test were to have reached the highest dose of ergonovine, the detection of electrocardiographic changes (ST segment deviation of 1 mm or more in at least 2 contiguous leads) or wall motion abnormalities (transient worsening of myocardial function in at least 2 contiguous segments) that led to suspicion of ischemia, significant arrhythmias, symptomatic hypertensive or hypotensive response (systolic blood pressure > 200 or < 90 mmHg, respectively), or symptoms which forced a premature end to the test. At the end of each study, an intravenous bolus of diltiazem (0.125 mg/kg) was administered to all patients. The criteria for considering a test as abnormal were the detection of electrocardiographic or wall motion abnormalities that suggested ischemia, with or without associated symptoms.

We included the following patient baseline characteristics: age, gender, current or ex-smoker, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, chronic kidney disease, and antecedents of myocardial infarction, typical and variant angina, and surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization), interruption of treatment that could modify the test accuracy, number and results of prior tests (coronary angiography, dobutamine or dipyridamole stress echocardiography, nuclear perfusion imaging and exercise tests) and indication, time between the studied event and ergonovine stress echocardiography, and its results (positive tests and criteria for positivity, affected territory, symptoms, dose of ergonovine administered, complications and blood pressure and heart rate at baseline and during the maximum stress stage). Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Data are shown as average ± SD or as number and percentage. Continuous variables were analyzed with the t test for paired samples. Quantitative variables were analyzed with the chi-square or Fisher test. We considered a difference as statistically significant when the P value was < 0.05.

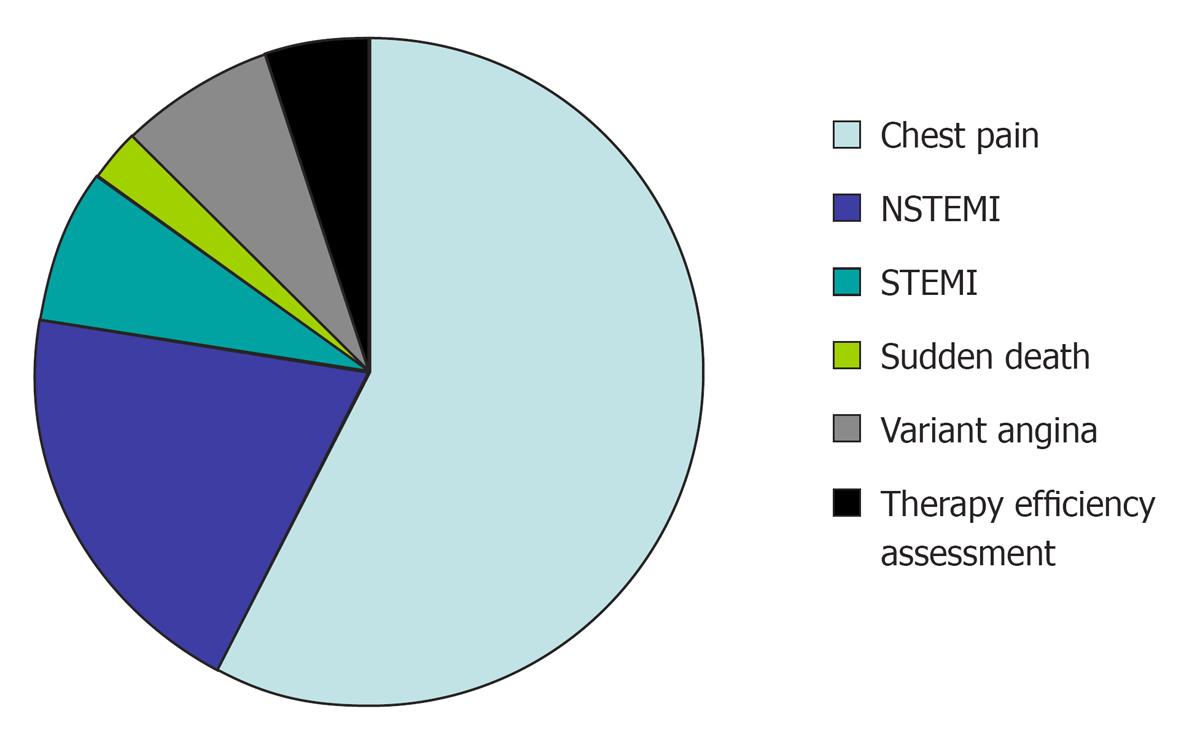

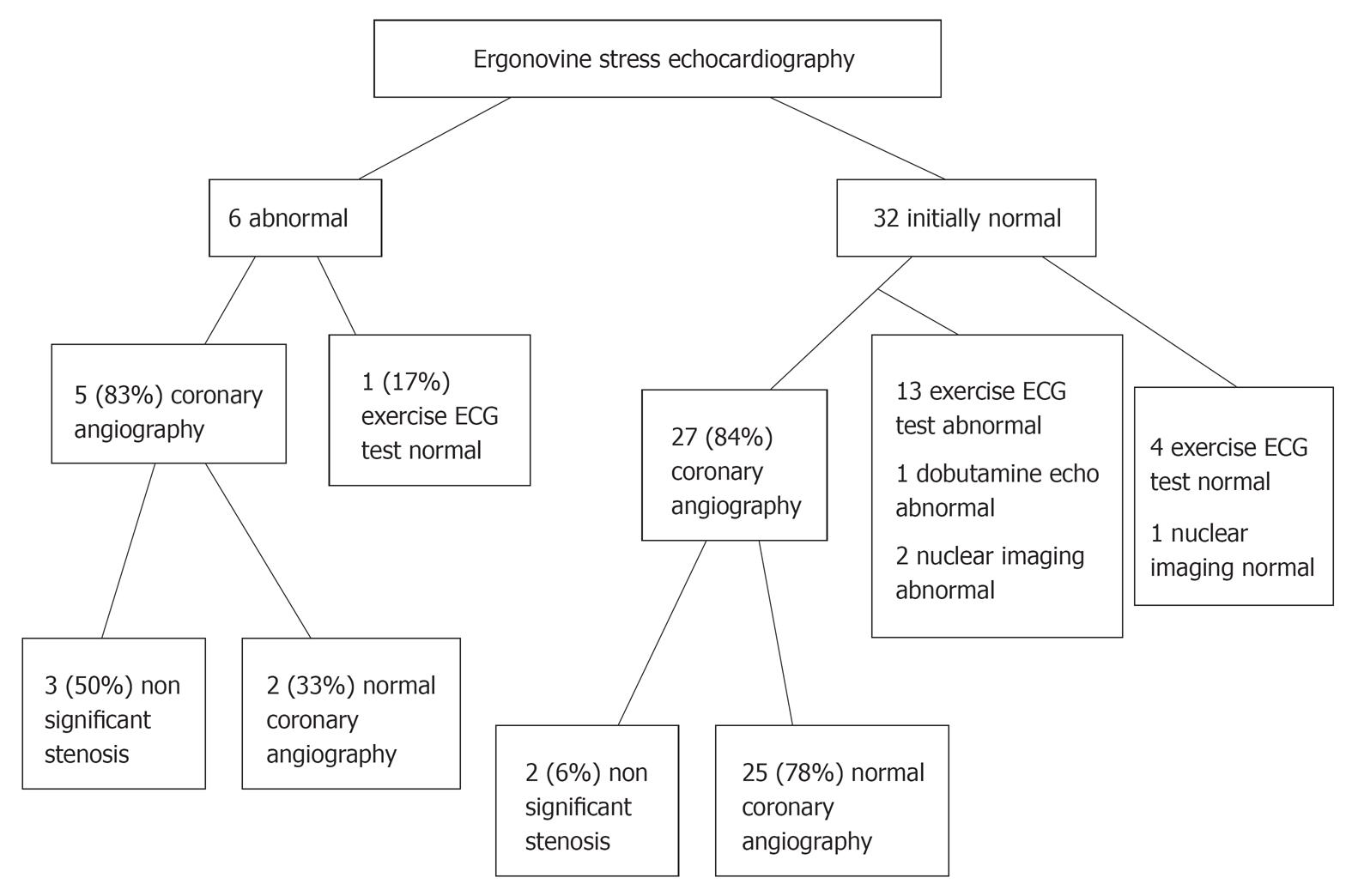

There were 40 tests carried out in 38 patients, 2 tests were performed to verify the efficacy of therapy with calcium channel blockers. Baseline characteristics and test indications are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively. The criteria for requesting these tests were based on the clinical suspicion of coronary vasospasm as the reason for the clinical picture studied, after rejecting the possibility of inducible ischemia or significant coronary artery stenosis. Before ergonovine stress echocardiography, all patients underwent an ischemia test or coronary angiography. Coronary angiography was performed in 32 patients, and showed normal coronary arteries in 27 patients and non-significant stenosis in 5 cases, all confirmed by flow coronary reserve measurement. The percentage of stenosis in patients with non-significant coronary artery disease was 35% in 2 cases and 30%, 28% and 25% in the other 3 patients, which was performed by quantitative assessment. In 16 cases, coronary angiography was carried out after a positive or inconclusive ischemia test. Another 6 patients had a normal stress test (5 exercise electrocardiography tests and 1 nuclear imaging test). Among the group with an abnormal ergonovine stress echocardiography, 3 patients (50%) had a non-significant stenosis in the vessel related to ischemia during the test, while among the group with an initial negative ergonovine stress echocardiography only 6% had a non-significant stenosis (Figure 2); this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.038). With regard to the baseline characteristics of the patients and the clinical picture studied, there were no significant differences between patients with a positive and negative ergonovine stress echocardiography. A baseline echocardiography was performed in all patients, and was normal in 28 (74%). Findings included 1 case (2.6%) of stress cardiomyopathy in relation to transient apical dyskinesia, 1 case of mild rheumatic mitro-aortic valvulopathy (mild aortic stenosis with mild mitral stenosis), 1 case of non-obstructive septal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and 1 case of non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, due to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging that did not show late gadolinium enhancement and suggested ischemic necrosis.

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 55 ± 12.11 |

| Masculine gender | 24 (63) |

| Active smokers | 14 (37) |

| Ex-smokers | 4 (10.5) |

| Alcohol consumption > 2 drinks/d | 6 (16) |

| Arterial hypertension | 17 (48) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (13) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 15 (39) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (5) |

| Antecedents of myocardial infarction | 1 (2.6) |

| Antecedents of typical angina | 2 (5) |

| Antecedents of variant angina | 3 (8) |

| Antecedents of percutaneous coronary revascularization | 2 (5) |

| Antecedents of surgical coronary revascularization | 1 (2.6) |

The ergonovine stress echocardiography results are shown in Table 2. Among the 6 abnormal cases, 4 were related to the right coronary artery territory while 2 were related to the circumflex coronary artery territory, without multivessel spasm. Among the positive tests, all patients presented with wall motion abnormalities and 5 (83%) had chest pain, whereas only 3 (50%) presented with significant ST segment changes, that consisted of ST segment elevation of at least 1 mm in 2 contiguous leads in all cases (2 in inferior leads and 1 in lateral leads). On the other hand, 1 patient had chest pain with the highest ergonovine dose with neither worsening in regional myocardial function nor significant electrocardiographic changes (only a diffuse decrease in T wave voltage), that was attributed to a dose-dependent diffuse coronary vasoconstriction.

| Positive tests | 6 (15) |

| Transient segment function worsening | 6 (15) |

| Dynamic ischemia in electrocardiogram | 3 (7.5) |

| Chest pain during the test | 6 (15) |

| Hypertensive reaction | 2 (5) |

| Sustained tachy or bradyarrhythmias | 0 (0) |

| Complications | 1 (2.5) |

| Mild adverse reactions | 16 (40) |

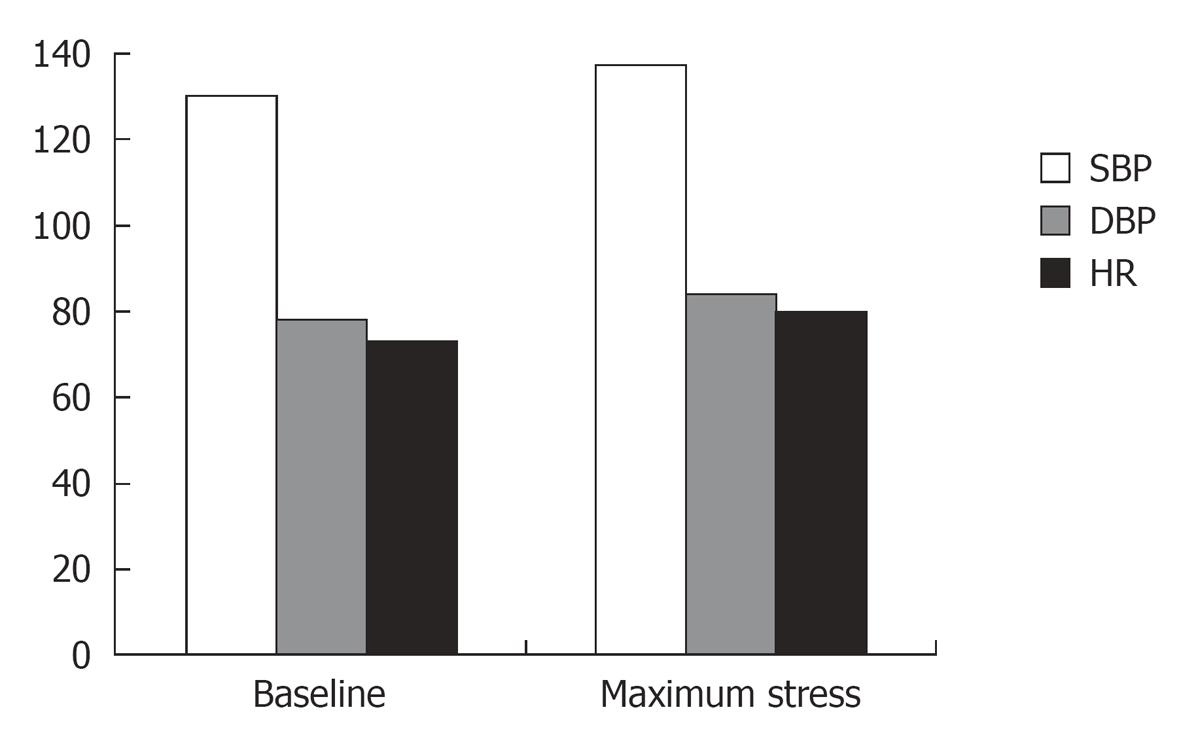

In 16 tests (40%) the patients developed an adverse effect: headache (10 cases), nausea (4 cases) and anxiety (2 cases). There was a hypertensive response in 2 patients (highest systolic blood pressure 200 mmHg in both patients) in the last stress stage, which did not force a premature end to the test. A statistical trend was found where higher systolic blood pressure values were observed during the test (95% CI: -12.77 to 0.14, P = 0.055) and significant differences were noted in relation to higher diastolic blood pressure values (95% CI: -10.41 to -1.69, P = 0.008) and heart rate (95% CI: -9.46 to -4.11, P < 0.01). Blood pressure and heart rate values are shown in Figure 3. A unique and serious complication was a prolonged vasospasm in the lateral segments with 0.15 mg of ergonovine, which led to a mild increase in necrosis biomarkers (highest troponin I = 10.2 ng/mL), but without wall motion abnormalities in the control echocardiography performed 1 mo later. This patient had presented with a non ST elevation myocardial infarction, and coronary angiography showed a luminal stenosis of 30% in the first diagonal branch. The other 5 positive cases improved rapidly with intravenous nitrates.

The time between the studied event and the ergonovine stress echocardiography was, in cases with elevation of necrosis biomarkers, 56 ± 11 d, and 3 ± 1 d for the remaining cases. In all patients, treatments that could modify the test results were withdrawn at least 48 h before the ergonovine stress echocardiography, with the exception of 2 cases in which the aim was to show treatment efficacy and who had a prior abnormal stress test. The total dose of ergonovine administered was 0.15 mg in 2 studies (5%) that were abnormal, and 0.35 mg in the other cases (average dose 0.34 ± 0.04 mg).

Among patients referred for ergonovine stress echocardiography, the prevalence of classic cardiovascular risk factors was low and the most frequent indication was chest pain. This technique allowed us to orientate the clinical picture diagnosis to coronary vasospasm in 15% of tests. Although there was a mild increase in blood pressure and heart rate, this technique was well tolerated in the majority of patients. The test was safe, resulting in the unique complication a prolonged vasospasm with a slight increase in necrosis biomarkers, but without wall motion abnormalities on control echocardiography. The presence of non-significant coronary stenosis was more frequent among the group of patients who had a positive ergonovine stress echocardiography, and these stenoses were related to the ischemic territory.

The induction of coronary vasospasm in patients who are suspected to have variant angina can occur in as many as 31% of Caucasian patients, and appears to be more common among east Asian patients[18]. Vasospasm may be related to a hypersensitivity to vasoconstrictor stimulus, with an imbalance between relaxing factors, such as nitric oxide, and constrictor factors released by the endothelium. Oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, high endothelin-1 activity and regional sympathetic denervation demonstrated by nuclear imaging may play an important part in the pathogenesis of coronary vasospasm[12,13,19-21].

Test positivity would support the diagnosis of coronary vasospasm, contributing to a complete differential diagnosis of chest pain, while if the test is normal, suspicion of vasospasm has to be based on treatment response and clinical picture. Vasospasm may be confirmed with Holter electrocardiography in cases with frequent symptoms, if it shows typical ischemic electrocardiographic changes[18,20].

Ergonovine stress echocardiography has demonstrated excellent accuracy in orientating the diagnosis of coronary vasospasm, compared with the invasive provocation test, with a sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 96%, positive predictive value of 96% and negative predictive value of 86%[12,22]. The fast recognition of wall motion abnormalities, information that is usually unavailable during invasive techniques, occur before electrocardiographic changes and onset of symptoms[23,24], and allow us to prevent complications related to ischemic waterfall. On the other hand, ergonovine stress echocardiography avoids the use of contrast and radiation associated with coronary angiography. One problem with this test may be the lack of a central venous approach for temporary pacing or an intracoronary catheter for intracoronary medicine infusion. However, with regard to its safety, several studies have reported a very low rate of complications, similar to dobutamine or dipyridamole, when appropriate patient selection is carried out by excluding those with significant stenosis and rapidly administering the antidote[9-13].

The most frequently affected territory is normally the one related to the left anterior descending coronary artery, followed by the right coronary artery[9,10]. In our study the latter territory was the most common; this situation may be explained by the smaller sample size compared with another studies.

Consistent with the literature, an important number of positive cases did not have electrocardiographic changes; this finding does not support the performance of techniques with only electrocardiographic monitoring[12,13,22].

Among the patients with positive tests, 5 (83%) developed chest pain, while only 1 patient with a negative test had chest pain with the highest ergonovine dose, but without worsening of myocardial wall motion or significant electrocardiographic changes. Chest pain is not a variable systematically registered in other studies because it is not a criterion for a positive response[3,12,14,15,20,22]. In one study in which 52 patients with acute coronary syndrome and normal or near-normal coronary angiograms were enrolled[13], chest pain was registered in 19 cases (76%) with positive ergonovine stress echocardiography and in 4 patients (15%) in the group with a negative test. These data were similar to the data found in the present study.

With regard to prognosis, patients with a positive test seemed to have more frequent events and a lower survival during follow-up, although these patients continued with the treatment. This was more evident in smokers or if there had been a multivessel spasm[11].

In this study, we found a higher rate of non-significant stenosis on coronary angiography in patients with a positive ergonovine stress echocardiography compared with patients who had a negative test. Thus, we expect that with the extension of non-invasive coronary angiography[7,8,25] and the uncertain meaning of non-significant coronary artery stenosis, the request for ergonovine stress echocardiography will increase in the near future. On the other hand, we are aware of not having performed coronary angiography in all patients, and the real rate of cases with non-significant stenosis and a negative ergonovine stress echocardiography may be higher. Thus, these findings have to be interpreted with caution.

There are other possible uses for ergonovine stress echocardiography. This technique may be useful for determining the cause of acute heart failure without structural or coronary heart disease, due to the fact that it has been described as severe mitral regurgitation related to spasm of a posterior branch, which can be manifested during an ergonovine stress test[26]. This technique could have additional value in the differential diagnosis between stress cardiomyopathy and coronary vasospasm, as several studies have demonstrated that this test is negative in stress cardiomyopathy. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of this pathology remains complex especially in patients with transient apical dyskinesia and normal coronary angiography[27,28].

Our data suggest that ergonovine stress echocardiography can be performed with safety in the majority of patients, usually with good tolerance.

Thus, based on our experience, we consider that ergonovine stress echocardiography is a safe and useful technique for orientating the ischemia mechanism if patients are appropriately selected on the basis of either previous normal coronary angiography, normal exercise electrocardiography or pharmacological stress test, contributing to a more complete differential diagnosis of chest pain.

The diagnosis of coronary vasospasm is often complicated. Frequently, there is no documentation of the initial clinical picture, and the unique tests available for diagnosis orientation in these situations are the vasospasm provocation techniques. A positive result in these tests supports the diagnosis of coronary vasospasm, contributing to a more complete differential diagnosis of chest pain.

Ergonovine stress echocardiography has demonstrated excellent accuracy for the diagnosis of coronary vasospasm, compared with the invasive provocation tests, and has many advantages compared with these tests. With regard to prognosis, patients with a positive test seemed to have more frequent events and a lower survival during follow-up, and this was more evident in smokers or if there had been a multivessel spasm.

The safety of vasospasm provocation techniques has been questioned. However, there are a number of studies that have demonstrated that ergonovine stress echocardiography is a safe tool for vasospasm diagnosis, with a very low rate of complications if patients are appropriately selected on the basis of either previous normal coronary angiography or normal exercise electrocardiography or pharmacological stress test. Several studies have reported a very low rate of complications, similar to dobutamine or dipyridamole stress echocardiography, when appropriate patient selection is carried out, and rapidly administering the antidote.

In this study we have registered a higher rate of non-significant stenosis on coronary angiography in patients with positive ergonovine stress echocardiography compared with patients who had a negative test, and these stenoses were related to the ischemic territory. We expect that with the extension of non-invasive coronary angiography and the uncertain meaning of non-significant coronary artery stenosis, the request for ergonovine stress echocardiography will increase in the near future. Based on our experience, ergonovine stress echocardiography can be performed with safety in the majority of patients, usually with good tolerance, and we consider it a safe and useful technique for orientating the ischemia mechanism if patients are appropriately selected.

Coronary vasospasm: a sudden constriction of a heart blood vessel, causing a reduction in local blood flow that can provoke a myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography: Examination of the heart blood vessels using x-rays following the injection of a radiopaque substance. Echocardiography: examination of the heart using ultrasound techniques. Ergonovine: an alkaloid derived from ergot that induces muscular contraction. It can be used for assessing the predisposition to a coronary vasospasm. Myocardial infarction: destruction of an area of heart muscle as the result of occlusion of a coronary artery.

This is a well-written paper dealing with the topic of ergonovine stress echocardiography. The authors studied 40 patients with this method and report their experience. All the patients had either normal or non-significant coronary angiography or normal stress tests before ergonovine stress echocardiography. The test was positive in 6 patients. No complications were registered.

Peer reviewers: Jesus Peteiro, MD, PhD, Unit of Echocardiography and Department of Cardiology, Juan Canalejo Hospital, A Coruna University, A Coruna, P/ Ronda, 5-4º izda, 15011, A Coruña, Spain; Dr. Thomas Jax, Profil Institut für Stoffwechselforschung, Hellersbergstrasse 9, Neuss 41460, Germany

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Maseri A, L'Abbate A, Baroldi G, Chierchia S, Marzilli M, Ballestra AM, Severi S, Parodi O, Biagini A, Distante A. Coronary vasospasm as a possible cause of myocardial infarction. A conclusion derived from the study of "preinfarction" angina. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:1271-1277. |

| 2. | Waters DD, Szlachcic J, Miller D, Theroux P. Clinical characteristics of patients with variant angina complicated by myocardial infarction or death within 1 month. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:658-664. |

| 3. | Fukai T, Koyanagi S, Takeshita A. Role of coronary vasospasm in the pathogenesis of myocardial infarction: study in patients with no significant coronary stenosis. Am Heart J. 1993;126:1305-1311. |

| 4. | Cheng TO. Provocative tests for coronary artery spasm. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:497-498. |

| 5. | Schroeder JS. Provocative testing for coronary artery spasm. Cardiovasc Clin. 1985;15:83-96. |

| 6. | Pepine CJ. Ergonovine echocardiography for coronary spasm: facts and wishful thinking. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1162-1163. |

| 7. | Fazel P, Peterman MA, Schussler JM. Three-year outcomes and cost analysis in patients receiving 64-slice computed tomographic coronary angiography for chest pain. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:498-500. |

| 8. | Chow BJ, Abraham A, Wells GA, Chen L, Ruddy TD, Yam Y, Govas N, Galbraith PD, Dennie C, Beanlands RS. Diagnostic accuracy and impact of computed tomographic coronary angiography on utilization of invasive coronary angiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:16-23. |

| 9. | Djordjevic-Dikic A, Varga A, Rodriguez O, Morelos M, Sicari R, Del Negro B, Morales MA, Carpeggiani C, Picano E. Safety of ergotamine-ergic pharmacologic stress echocardiography for vasospasm testing in the echo lab: 14 year experience on 478 tests in 464 patients. Cardiologia. 1999;44:901-906. |

| 10. | Pálinkás A, Picano E, Rodriguez O, Diordjevic-Dikic A, Landi P, Varga A, Ghelarducci B. Safety of ergot stress echocardiography for non-invasive detection of coronary vasospasm. Coron Artery Dis. 2001;12:649-654. |

| 11. | Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH, Hong MK, Lee CW, Song JM, Kim JJ, Park SJ. Prognostic implication of ergonovine echocardiography in patients with near normal coronary angiogram or negative stress test for significant fixed stenosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:1346-1352. |

| 12. | Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Lee CW, Park SJ. Safety and clinical impact of ergonovine stress echocardiography for diagnosis of coronary vasospasm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1850-1856. |

| 13. | Kim MH, Park EH, Yang DK, Park TH, Kim SG, Yoon JH, Cha KS, Kum DS, Kim HJ, Kim JS. Role of vasospasm in acute coronary syndrome: insights from ergonovine stress echocardiography. Circ J. 2005;69:39-43. |

| 14. | Song JK, Lee SJ, Kang DH, Cheong SS, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Park SW, Park SJ. Ergonovine echocardiography as a screening test for diagnosis of vasospastic angina before coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1156-1161. |

| 15. | Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH, Lee CW, Choi KJ, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Kim YH, Park SJ. Diagnosis of coronary vasospasm in patients with clinical presentation of unstable angina pectoris using ergonovine echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1475-1478. |

| 16. | Cheng TO. Ergonovine echocardiography for the diagnosis of coronary vasospasm. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:641. |

| 17. | Siegel W. The first provocative test for coronary artery spasm at the Cleveland Clinic. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1198-1199. |

| 18. | Pristipino C, Beltrame JF, Finocchiaro ML, Hattori R, Fujita M, Mongiardo R, Cianflone D, Sanna T, Sasayama S, Maseri A. Major racial differences in coronary constrictor response between japanese and caucasians with recent myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101:1102-1108. |

| 19. | Beltrame JF, Sasayama S, Maseri A. Racial heterogeneity in coronary artery vasomotor reactivity: differences between Japanese and Caucasian patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1442-1452. |

| 20. | Bertrand ME, LaBlanche JM, Tilmant PY, Thieuleux FA, Delforge MR, Carre AG, Asseman P, Berzin B, Libersa C, Laurent JM. Frequency of provoked coronary arterial spasm in 1089 consecutive patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Circulation. 1982;65:1299-1306. |

| 21. | Hung MJ. Current advances in the understanding of coronary vasospasm. World J Cardiol. 2010;2:34-42. |

| 22. | Song JK, Park SW, Kim JJ, Doo YC, Kim WH, Park SJ, Lee SJ. Values of intravenous ergonovine test with two-dimensional echocardiography for diagnosis of coronary artery spasm. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1994;7:607-615. |

| 23. | Distante A, Rovai D, Picano E, Moscarelli E, Morales MA, Palombo C, L'Abbate A. Transient changes in left ventricular mechanics during attacks of Prinzmetal angina: a two-dimensional echocardiographic study. Am Heart J. 1984;108:440-446. |

| 24. | Rovai D, Distante A, Moscarelli E, Morales MA, Picano E, Palombo C, L'Abbate A. Transient myocardial ischemia with minimal electrocardiographic changes: an echocardiographic study in patients with Prinzmetal's angina. Am Heart J. 1985;109:78-83. |

| 25. | Nieman K, Galema T, Weustink A, Neefjes L, Moelker A, Musters P, de Visser R, Mollet N, Boersma H, de Feijter PJ. Computed tomography versus exercise electrocardiography in patients with stable chest complaints: real-world experiences from a fast-track chest pain clinic. Heart. 2009;95:1669-1675. |

| 26. | Epureanu V, San Román JA, Vega JL, Fernández-Avilés F. [Acute pulmonary edema with normal coronary arteries: mechanism identification by ergonovine stress echocardiography]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2002;55:775-777. |

| 27. | Previtali M, Repetto A, Panigada S, Camporotondo R, Tavazzi L. Left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: prevalence, clinical characteristics and pathogenetic mechanisms in a European population. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:91-96. |

| 28. | Parodi G, Del Pace S, Carrabba N, Salvadori C, Memisha G, Simonetti I, Antoniucci D, Gensini GF. Incidence, clinical findings, and outcome of women with left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:182-185. |