Published online Dec 26, 2010. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i12.403

Revised: September 23, 2010

Accepted: September 30, 2010

Published online: December 26, 2010

Acute and recurring pericarditis are frequently encountered clinical entities. Given that severe complications such as tamponade and constrictive pericarditis occur rarely, the majority of patients suffering from acute pericarditis will have a benign clinical course. However, pericarditis recurrence, with its painful symptoms, is frequent. In effect, recent studies have demonstrated a beneficial role of colchicine in preventing recurrence, while also suggesting an increase in recurrences with the use of corticosteroids, the traditional first-line agent.

- Citation: Farand P, Bonenfant F, Belley-Côté EP, Tzouannis N. Acute and recurring pericarditis: More colchicine, less corticosteroids. World J Cardiol 2010; 2(12): 403-407

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v2/i12/403.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v2.i12.403

Pericarditis is a frequently encountered clinical entity. Studies have shown that pericarditis accounts for 5% of the final diagnoses among patients consulting in the emergency department for non-anginal chest pain[1]. Few studies have addressed the treatment of acute and recurring pericarditis and, until recently, recommendations were based on a few small studies. Moreover, one of the most complete publications on the subject, the “Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases” from the European Society of Cardiology[2], is based predominantly on expert opinion. However, in the past decade, several clinical studies have been published on pericarditis, mainly from Italian and Israeli researchers. A recent publication in Circulation[3] and a publication from our group[4] summarized these studies. It is important to note that some of these studies reinforce the current recommendations to use corticosteroids only in cases of treatment failure or intolerance to other treatments and support the use of colchicine, even for a first episode.

This article focuses on the treatment of pericarditis after a brief exploration of its pathophysiology, diagnosis and prognosis. Other pericardial pathologies such as constrictive pericarditis, chronic pericardial effusion and tamponade will not be discussed.

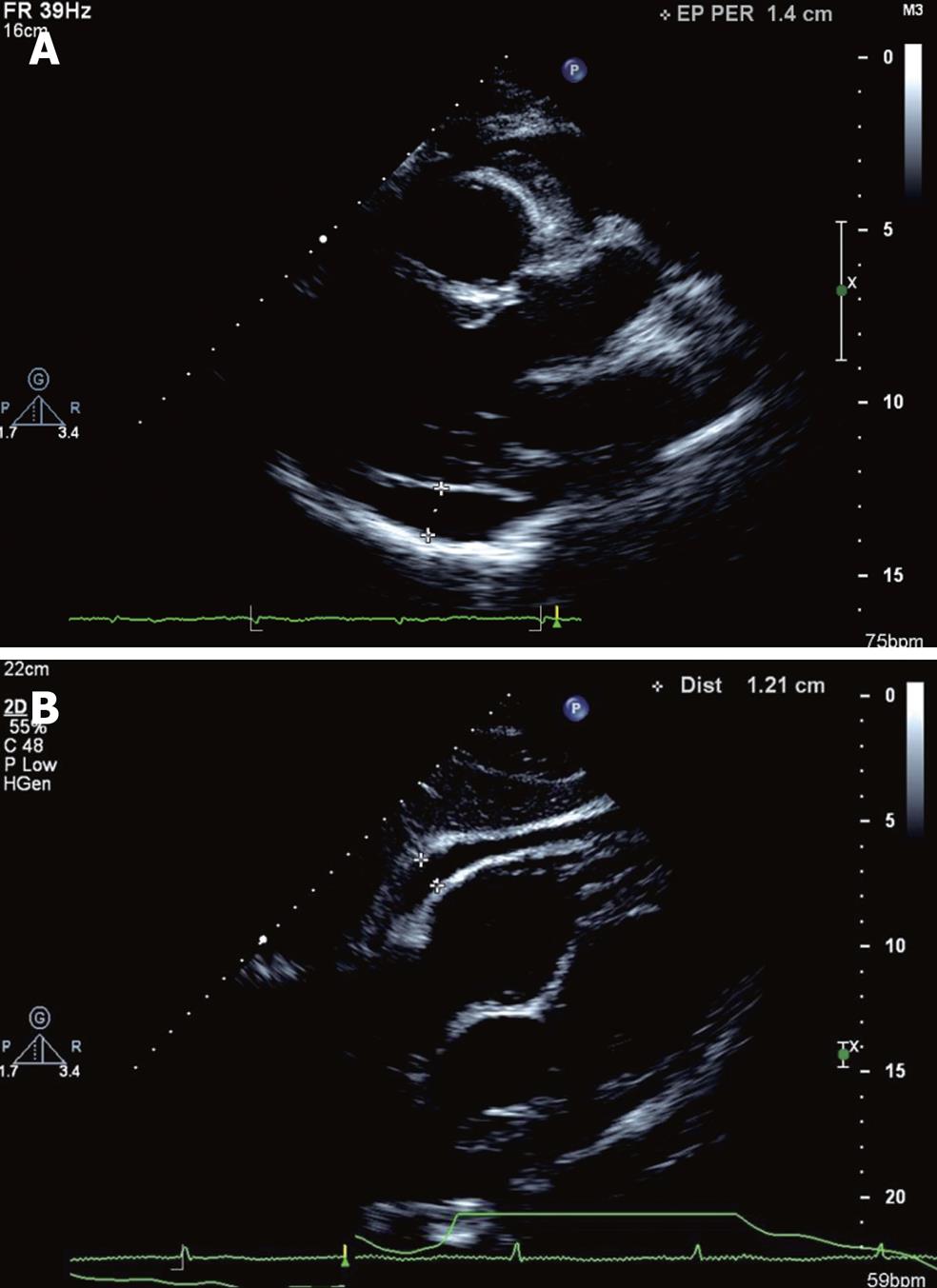

The pericardial space is bordered by two layers: the fibrous pericardium and the visceral pericardium. The later is in close contact with the epicardial fat. In normal conditions, a small amount of liquid (25-30 mL) is present in the pericardial space which prevents friction between the two layers of the pericardium and, as a result, between the beating heart and adjacent structures[2] (Figure 1).

The most frequent pericardial disease is acute pericarditis. Most cases are idiopathic and assumed to result from viral infection. Other frequent, non-infectious etiologies are autoimmune disease, neoplasia and iatrogenic (i.e. post-cardiac procedures). Pericarditis due to tuberculosis is mainly seen in developing countries[5]. After years of decreasing prevalence, the frequency of tuberculous pericarditis has been increasing in the context of the HIV epidemic.

Inflammation of the pericardial layers leads to increasing exudation of fluid while decreasing the normal pericardial drainage by the lymphatic ducts. Thus, inflammation often leads to pericardial effusion. Although usually small, if sufficient, this volume of liquid can impinge on the filling of the right cardiac chambers, culminating with tamponade. Pericardial effusion occurring in a context of acute pericarditis is distinguished from chronic effusion by the fact that the effusion regresses when the inflammation resolves and the pericardium resumes its normal functions. On the other hand, chronic inflammation can lead to fibrosis and rigidity of the pericardium, as seen in constrictive pericarditis.

Tamponade and constrictive pericarditis are the most serious complications of acute pericarditis. Tamponade can be life-threatening: the accumulated fluid causes compression of the cardiac chambers, preventing their filling. Prompt treatment is vital and consists in removal of the pericardial effusion, usually via pericardiocentesis. In contrast, in constrictive pericarditis, compression of the cardiac cavities results from a stiffened pericardium. Constrictive pericarditis presents with right heart failure and low cardiac output. The definitive treatment of this pathology is surgical removal of the pericardium, a high risk procedure. Fortunately, both of these complications rarely arise following acute or recurring pericarditis such as demonstrated in a review of several clinical studies on pericarditis. This review reports that 3 % of patients with recurring pericarditis evolved towards tamponade and only 1 out of 296 patients developed constrictive pericarditis[6].

Several studies have tried to identify patients at high risk for the development of complications from an episode of acute pericarditis. Their goal was to determine the patients who would benefit from hospitalization for surveillance. High-risk features included: a pericardial effusion more than 20 mm, risk factors for hemorrhagic pericardial effusion (anticoagulation, neoplasia, accidental or iatrogenic thoracic trauma), temperature above 38°C, myopericarditis, pulsus paradoxus, evidence of systemic inflammation, subacute evolution (in contrast to acute) and, finally, patients with treatment failure[7]. However, it is important to note that the majority of patients present none of these characteristics. Besides identifying the patients with a higher risk of complications, these characteristics can also help identifying those for whom a precise etiology is more likely to be discovered and who would benefit from a more extensive investigation.

A significant proportion of patients with acute pericarditis also present a certain degree of myocarditis, possibly because they share several common etiologies, in particular viral infections. Detection of these patients relies on an elevation of cardiac biomarkers (troponins, CK-MB) and a new left ventricular dysfunction as usually demonstrated by echocardiography[8]. Besides providing hemodynamic support, if needed, guideline recommended therapy for non-ischemic left ventricular dysfunction is advised (β-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors). Moreover, because of their possible harmful effects on myocarditis, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be used with caution in perimyocarditis. It is recommended to use a lower dosage and to favour the use of acetylsalicylic acid. However, some causes of myocarditis require specific treatments, as described in a recent New England Journal of Medicine article[9].

The main concern in the evolution of acute pericarditis lies in the high rate of recurrences, which occur, on average, in 24 % of patients, according to the biggest case-series available[10]. This rate is approximately twice as frequent in recurring pericarditis.

Two out of four criteria are required to diagnose acute pericarditis. They include the presence of (1) a characteristic chest pain; (2) diffuse ST elevations; (3) a pericardial rub; and (4) a pericardial effusion[11].

If suspected, the basic investigation, after history and physical examination, should include the following: an electrocardiogram, a chest X-ray, a transthoracic echocardiogram, cardiac biomarkers (troponins and creatine kinase), markers of inflammation [C-reactive protein (CRP) and sedimentation rate] as well as a complete blood count and a basic renal function profile. A more extensive workup is usually not required because the majority of pericarditis cases, seen in the emergency department in developed countries, are idiopathic. If a specific etiology is suspected, such as neoplasia, systemic disease, or tuberculosis, appropriate investigations should be performed[3].

Pericardial diseases are one of the few areas in cardiovascular medicine without multiple practice guidelines. The European Society of Cardiology is the only major organisation that has established guidelines concerning pericardial diseases (2004). Moreover, these guidelines are mainly based on expert opinion because, until recently, few randomized controlled trials were available. In the past few years, several trials explored the subject, particularly regarding the role of colchicine and corticosteroids as treatments for acute and recurring pericarditis. This section will discuss these treatments in further detail.

Although there is no large study on the use of anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of acute and recurring pericarditis, they remain the cornerstone of treatment. Clinical experience shows that in order to prevent treatment failure, both the dosage of NSAIDs and the duration of treatment must be adequate[2]. Recommended dosages and tapering are presented in Table 1. Tapering of NSAIDs should not be attempted before complete resolution of symptoms. Also, the follow-up of inflammatory markers, such as CRP, should guide the tapering. It is recommended to wait for their normalization before every decrease in dosage[3].

| Drugs | Discharge dose (adults) | Tapering (wait until symptom free and normal CRP) | Monitoring/follow-up (in addition to follow-up for the clinical condition) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid (preferred for patients with known atherosclerosis) | 650 mg po qid for 1-2 wk (2-4 wk when recurring) | Taper the dose by 30 % every 1-2 wk then stop | -Use gastric protection |

| Ibuprofen | 600 mg po tid for 1-2 wk (2-4 wk when recurring) | Taper the dose by 30 % every 1-2 wk then stop | -Use gastric protection |

| Indomethacin | 50 mg po tid for 1-2 wk (2-4 wk when recurring) | Taper the dose by 30 % every 1-2 wk then stop | -Use gastric protection |

| Colchicine | 0.5 mg (or 0.6 mg) po bid for 3 mo (6 mo when recurring) | - | -Adjust for renal function |

| Use 0.5 mg (or 0.6 mg) po daily in patients intolerant to higher doses, over 70 yr old or less than 70 kg | -AST ALT CK, creatinine initially, then at 1 mo | ||

| Prednisone | 0.2-0.5 mg/kg po daily for 2 wk (2-4 wk when recurring) | -Taper the dose by 10% every 1-2 wk | -Osteoporosis prophylaxis |

| -Taper slowly, especially when it comes to 15 mg/d, where decreases could be as low as 1.0 mg/d every 6 wk |

Corticosteroids are often used in acute and recurring pericarditis because of their ability to quickly induce a positive clinical response. However, recent recommendations limit their role because of the lack of clinical evidence showing medium and long-term benefit. Indeed, the use of corticosteroid therapy for recurring pericarditis is only supported by a retrospective study of 12 patients treated with high doses of prednisone[12].

Recent data identified the use of corticosteroids as being a factor favoring the recurrence of pericarditis. High vs low dosage of corticosteroids in the treatment of recurring pericarditis was evaluated in a retrospective study of 100 patients[13]. The high dose group not only experienced more side effects, mainly osteoporosis, but also had more recurrences of pericarditis and hospitalizations. This increase in recurrences was also observed in two retrospective observational studies[1,14].

These findings are reflected in the European recommendations which limit the use of corticosteroids to refractory and recurring pericarditis or in cases of intolerance, contraindication or failure of the usual treatments (NSAIDs and colchicine)[15]. Patients receiving steroids for more than 3 mo should receive osteoporosis prophylaxis: calcium, vitamin D and bisphosphonates[16]. The proposed corticosteroid doses are inferred from the experience acquired in the treatment of serositis such as in lupus and other systemic inflammatory diseases. They are presented in Table 1. As with NSAIDs, corticosteroid tapering should begin only after the resolution of symptoms and normalization of the inflammatory markers.

The action of colchicine is mainly obtained through modulation of the cellular microtubule formation. Colchicine is mainly used in the treatment of gout and familial Mediterranean fever[17]. During the 1990s, the analysis of several small series of patients raised a potential benefit of colchicine in the prevention of pericarditis recurrences. However, it was only in 2005, with the publication of the CORE[18] and COPE[19] trials that colchicine was clearly demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of pericarditis.

The COPE trial was randomized although not blinded. One hundred and twenty patients were approached during their first episode of pericarditis and randomly assigned to an anti-inflammatory treatment alone or in combination with colchicine. The recurrences of pericarditis at 18 mo were 11% in the colchicine-treated group vs 32% for the group not receiving colchicine. Only 5 patients stopped colchicine because of diarrhea, the most frequent side effect of this medication.

Similarly, the CORE trial was randomized but not blinded. It recruited patients suffering from a first recurrence of pericarditis. Eighty-eight patients were randomized to an anti-inflammatory treatment alone or in association with colchicine. In the colchicine group, recurrence was at 24% vs 51% for the group not receiving colchicine.

Three randomized controlled trials, in progress since 2007, are exploring the use of colchicine in the treatment of acute[20] and recurring[21] pericarditis. Their results should allow clinicians to clarify the possible benefits of colchicine in the treatment of pericarditis. While waiting for these results, colchicine should be preferred over corticosteroids in the context of more robust data and a more favourable side effect profile associated with its use.

In refractory cases, investigations should focus on trying to identify a secondary cause of pericarditis, where specific treatments could be available, or a cause that could explain treatment failure.

Literature recommendations for patients with recurring pericarditis that is refractory to conventional treatments are sparse. First-line therapy consists in combining NSAIDs, colchicine and corticosteroids[3]. If this triple therapy fails, a trial of immunosuppressive agents can be attempted and proved successful in small trials. Azathioprine and methotrexate are the most often reported and less toxic of such agents[22]. It is important to note that, according to expert opinions, patients suffering from pericarditis should not participate in competitive sports for a period of 3 mo[23].

Acute and recurrent pericarditis are frequently encountered clinical entities. Since severe complications such as tamponade and constrictive pericarditis occur in rare cases, the majority of patients suffering from acute pericarditis will have a benign clinical course. However, recurrence of pericarditis with its painful symptoms is much more frequent. On this matter, recent studies have demonstrated a benefit of colchicine in reducing the risk of recurrence of pericarditis, while also suggesting an increase in recurrence with the use of corticosteroids, the traditional first-line agent.

Peer reviewers: Athanassios N Manginas, MD, FACC, FESC, Interventional Cardiology, 1st Department of Cardiology, Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center, 356 Sygrou Ave, Athens, 17674, Greece; Theodor Tirilomis, MD, PhD, FETCS, Department for Thoracic, Cardiac, and Vascular Surgery, University of G_ttingen, Robert-Koch-Str. 40, 37075 Goettingen, Germany

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Negro F E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Ghisio A, Belli R, Bobbio M, Trinchero R. Management, risk factors, and outcomes in recurrent pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:736-739. |

| 2. | Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, Erbel R, Rienmüller R, Adler Y, Tomkowski WZ, Thiene G, Yacoub MH. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:587-610. |

| 3. | Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, Trinchero R, Adler Y. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:916-928. |

| 4. | Farand P, Belley-Côté ÉP. Give a bigger place for colchicine and a smaller place for corticosteroids in the algorithm for the treatment of acute and recurring pericarditis. MedActuel. 2010;10:1-5. |

| 5. | Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, Ierna S, Demarie D, Ghisio A, Pomari F, Coda L, Belli R, Trinchero R. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115:2739-2744. |

| 6. | Imazio M, Trinchero R, Shabetai R. Pathogenesis, management, and prevention of recurrent pericarditis. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2007;8:404-410. |

| 8. | Imazio M, Trinchero R. Myopericarditis: Etiology, management, and prognosis. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:17-26. |

| 9. | Cooper LT Jr. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1526-1538. |

| 10. | Soler-Soler J, Sagristà-Sauleda J, Permanyer-Miralda G. Relapsing pericarditis. Heart. 2004;90:1364-1368. |

| 11. | Imazio M, Brucato A, Trinchero R, Adler Y. Diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:743-751. |

| 12. | Marcolongo R, Russo R, Laveder F, Noventa F, Agostini C. Immunosuppressive therapy prevents recurrent pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1276-1279. |

| 13. | Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, Brambilla G, Demichelis B, Ferro S, Maestroni S, Cecchi E, Belli R, Palmieri G. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667-671. |

| 14. | Artom G, Koren-Morag N, Spodick DH, Brucato A, Guindo J, Bayes-de-Luna A, Brambilla G, Finkelstein Y, Granel B, Bayes-Genis A. Pretreatment with corticosteroids attenuates the efficacy of colchicine in preventing recurrent pericarditis: a multi-centre all-case analysis. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:723-727. |

| 15. | Imazio M, Brucato A, Trinchero R, Shabetai R, Spodick D, Adler Y. Corticosteroid therapy for pericarditis: a double-edged sword. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:118-119. |

| 16. | Homik J, Cranney A, Shea B, Tugwell P, Wells G, Adachi R, Suarez-Almazor M. Bisphosphonates for steroid induced osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;CD001347. |

| 17. | Molad Y. Update on colchicine and its mechanism of action. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002;4:252-256. |

| 18. | Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Pomari F, Moratti M, Ghisio A, Belli R, Trinchero R. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the CORE (COlchicine for REcurrent pericarditis) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1987-1991. |

| 19. | Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Demichelis B, Pomari F, Moratti M, Gaschino G, Giammaria M, Ghisio A. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the COlchicine for acute PEricarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005;112:2012-2016. |

| 20. | Imazio M, Cecchi E, Ierna S, Trinchero R. Investigation on Colchicine for Acute Pericarditis: a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial evaluating the clinical benefits of colchicine as adjunct to conventional therapy in the treatment and prevention of pericarditis; study design amd rationale. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2007;8:613-617. |

| 21. | Imazio M, Cecchi E, Ierna S, Trinchero R. CORP (COlchicine for Recurrent Pericarditis) and CORP-2 trials--two randomized placebo-controlled trials evaluating the clinical benefits of colchicine as adjunct to conventional therapy in the treatment and prevention of recurrent pericarditis: study design and rationale. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2007;8:830-834. |

| 22. | Brucato A, Brambilla G, Adler Y, Spodick DH. Recurrent pericarditis: therapy of refractory cases. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2600-2601. |

| 23. | Pelliccia A, Corrado D, Bjørnstad HH, Panhuyzen-Goedkoop N, Urhausen A, Carre F, Anastasakis A, Vanhees L, Arbustini E, Priori S. Recommendations for participation in competitive sport and leisure-time physical activity in individuals with cardiomyopathies, myocarditis and pericarditis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:876-885. |