Published online Jul 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i7.106828

Revised: April 30, 2025

Accepted: June 27, 2025

Published online: July 26, 2025

Processing time: 136 Days and 17 Hours

Bothrops envenomation is a common medical emergency in tropical areas and is characterized by local and systemic complications, such as edema, coagulopathy, and tissue necrosis. Cardiovascular manifestations are rare and poorly docu

We described a rare cardiac complication in a 65-year-old female patient, who initially presented with mild Bothrops envenomation. She experienced localized edema and erythema but with a lack of systemic symptoms. During the eva

This case underscored the need for cardiac monitoring after snakebite envenomation as well as further research on venom-induced cardiotoxic mechanisms.

Core Tip: A 65-year-old female presented with mild Bothrops envenomation and developed unexpected cardiac complications, including sinus bradycardia and QTc prolongation. The cardiac complications progressed to severe arrhythmias requiring a pacemaker. Despite no initial systemic signs, intensive care, antivenom, and plasma transfusions were necessary for a successful recovery. This case underscored the need for cardiovascular monitoring after snakebites.

- Citation: Acosta JS, Cifuentes Tarquino J, Arteaga JE. Bothrops bite and cardiac complications: A case report and review of literature. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(7): 106828

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i7/106828.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i7.106828

The snake Bothrops is responsible for 80% of snakebite envenomation cases in Colombia, contributing to significant medical emergencies in rural areas[1]. According to the National Institute of Health, 4835 cases of Bothrops bites were reported in Colombia in 2024, with a national incidence of 9.11 cases per 100000 inhabitants[2]. Colombia is a tropical country with high ecosystem diversity and ranks third in Latin America (after Brazil and Mexico) in the number of snakebite envenomation cases annually[3]. On average 4467 snakebite cases occur each year, with the departments of Antioquia, Guaviare, and Vaupés reporting the highest incidence rates. Vaupés records up to 116.1 cases per 100000 inhabitants, highlighting the uneven burden of snakebite exposure across regions[4].

The most medically significant snake species belong to the Viperidae family and include Bothrops asper (B. asper), B. atrox, and Porthidium nasutum. B. asper is responsible for 70% of snakebite cases in the northwest, while B. atrox causes the majority of snakebite cases in the southern region[5]. These snakes are widely distributed in tropical rural areas where access to timely medical care and antivenom is often limited. Despite an estimated annual need of over 54000 vials of antivenom, only 21000 vials are produced each year in Colombia, leading to substantial gaps in access[4].

Globally, snakebite envenomation has been recognized as a high-impact public health problem, primarily affecting impoverished rural populations in tropical areas[6-8]. In 2017 the World Health Organization included envenomation in the list of neglected tropical diseases, setting a goal of a 50% reduction in related deaths and disabilities by 2030[9,10]. Snakebites produce local manifestations such as pain, edema, and tissue necrosis as well as systemic complications including coagulopathies, rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, and less frequently neurotoxic and cardiotoxic manifestations[11,12]. However, cardiac complications due to Bothrops envenomation are infrequent and rarely reported in patients without cardiovascular risk factors[13,14]. This report describes the unexpected finding of severe cardiac alterations, including QTc prolongation and severe arrhythmias, in a patient with Bothrops envenomation. The case itself underscores the importance of clinical recognition of these findings in toxicological emergencies and understanding their management and clinical implications.

A 65-year-old female presented with a Bothrops snakebite on the right first toe. She was experiencing localized pain, edema, and erythema.

The patient, a housewife residing in a rural area of Valle de San Juan, Tolima, was bitten approximately 6 hours before arriving at the primary care center. The snake was identified and classified as belonging to the genus Bothrops, based on its morphological characteristics (Figure 1). Initial symptoms included pain and edema at the site of the bite. An all-or-none test[15] confirmed envenomation, and four vials of polyvalent antiophidic serum were administered. During the initial evaluation, an incidental finding of asymptomatic sinus bradycardia and prolongation of the QTc interval on the electrocardiogram (QTc of 523 milliseconds) was documented. She was referred to a hospital with a higher level of care.

The patient had a history of arterial hypertension controlled by losartan and an untreated depressive disorder.

The patient was a non-smoker, denied alcohol or drug use, and reported no family history of heart disease, arrhythmia, sudden death, or known genetic disorders.

Upon admission to the tertiary care center, the patient was alert and oriented. Her vital signs included a temperature of 36.8 °C, heart rate of 48 beats/minute, respiratory rate of 19 breaths/minute, and blood pressure of 148/61 mmHg. Clinical findings included a regular rhythm with bradycardia and no murmurs, rubs, or cardiac gallop. Bilateral clear breath sounds were heard. A blister on the dorsum of the right foot with visible punctures on the first toe were observed. Erythema and edema extending to the distal third of the right leg were noted. There were no areas of necrosis and stigmata of mucosal bleeding. Sensation was preserved.

A complete summary of laboratory findings is presented in Table 1. Marked abnormalities were found in coagulation parameters and cardiac biomarkers, indicating severe coagulopathy and myocardial injury and cardiac dysfunction.

| Parameter | Result | Reference range |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.3 | 12-16 |

| Leucocytes, × 103/μL | 9.55 | 4.00-11.00 |

| Platelets, /μL | 217000 | 150000-400000 |

| Prothrombin time, seconds | > 120 | 10-14 |

| INR | > 5.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| Partial thromboplastin, seconds | 25.3 | 22.0-34.0 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | > 450 | 200-400 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 | 0.6-1.2 |

| Urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 20.6 | 7.0-20.0 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 3.4 | 3.5-5.0 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 141 | 135-145 |

| Magnesium, mg/dL | 3.4 | 1.7-2.2 |

| Ionic calcium, mmol/L | 1.05 | 1.12-1.30 |

| Troponin I, ng/L | 34.2 | 0-19.0 |

| CPK, U/L | 319 | 26-192 |

| TSH, mIU/L | 3.1 | 0.5-4.7 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 3067 | < 125 |

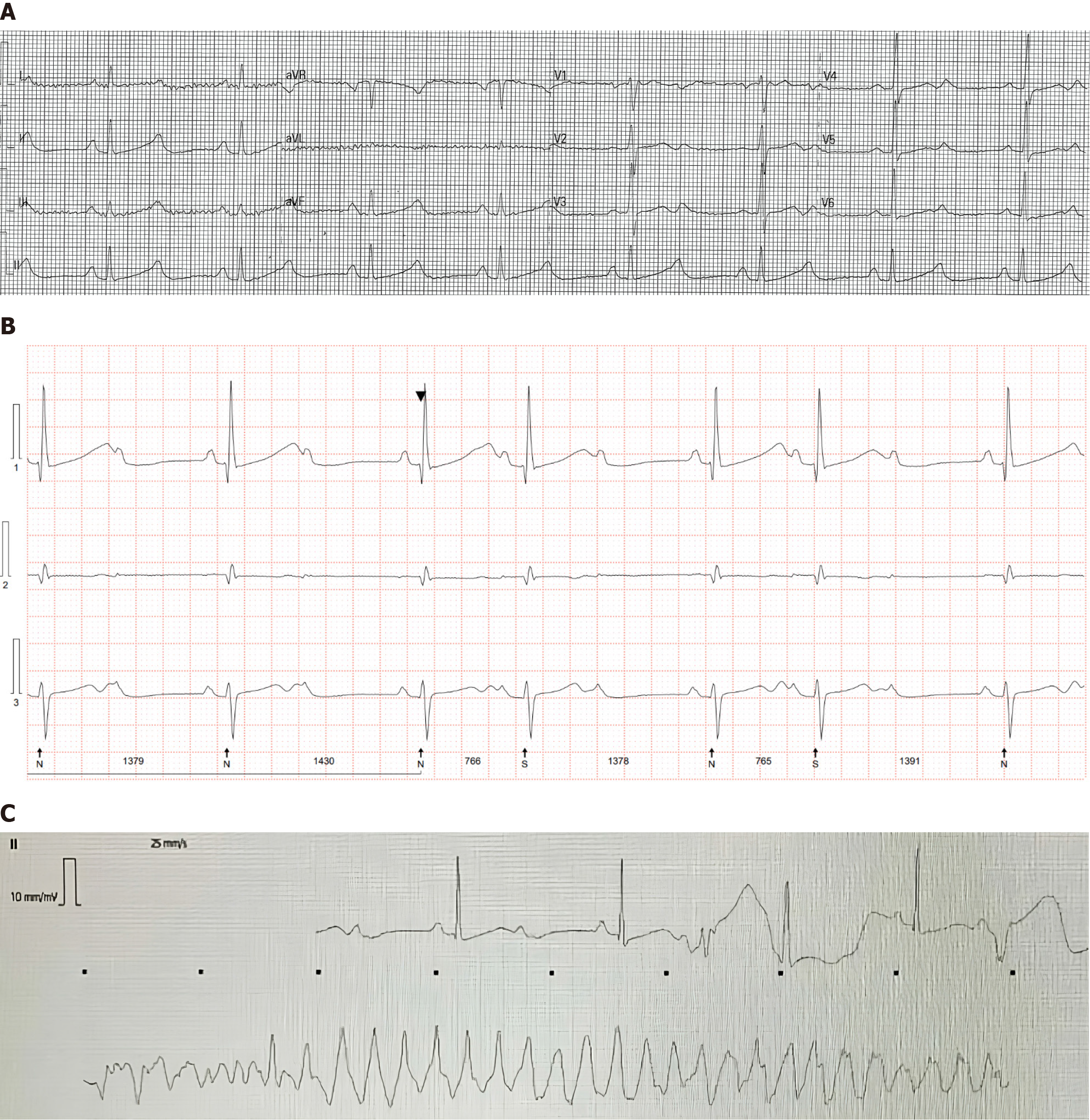

Imaging studies included an electrocardiogram. It showed sinus bradycardia with QTc prolongation (523 milliseconds according to Fridericia’s formula) (Figure 2A), normal systolic and diastolic function of the left ventricle, and left atrial dilatation (area: 23 cm2; volume: 39 mL/m2). Holter monitoring documented bradycardia with QTc prolongation (513 milliseconds) and episodes of advanced atrioventricular block that required transvenous pacing (Figure 2B).

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to assess the possible etiology of the atrioventricular block. However, the study could not be performed because of the patient’s dependence on a transvenous pacemaker. The clinical course included recurrent episodes of wide complex tachycardia and chest pain (Figure 2C). These findings, together with elevated troponin and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels (Table 1), led to coronary arteriography, which ruled out ischemia.

Bothrops envenomation complicated by sinus bradycardia, QTc prolongation, advanced atrioventricular block, wide complex tachycardia, and cardiac conduction disturbances.

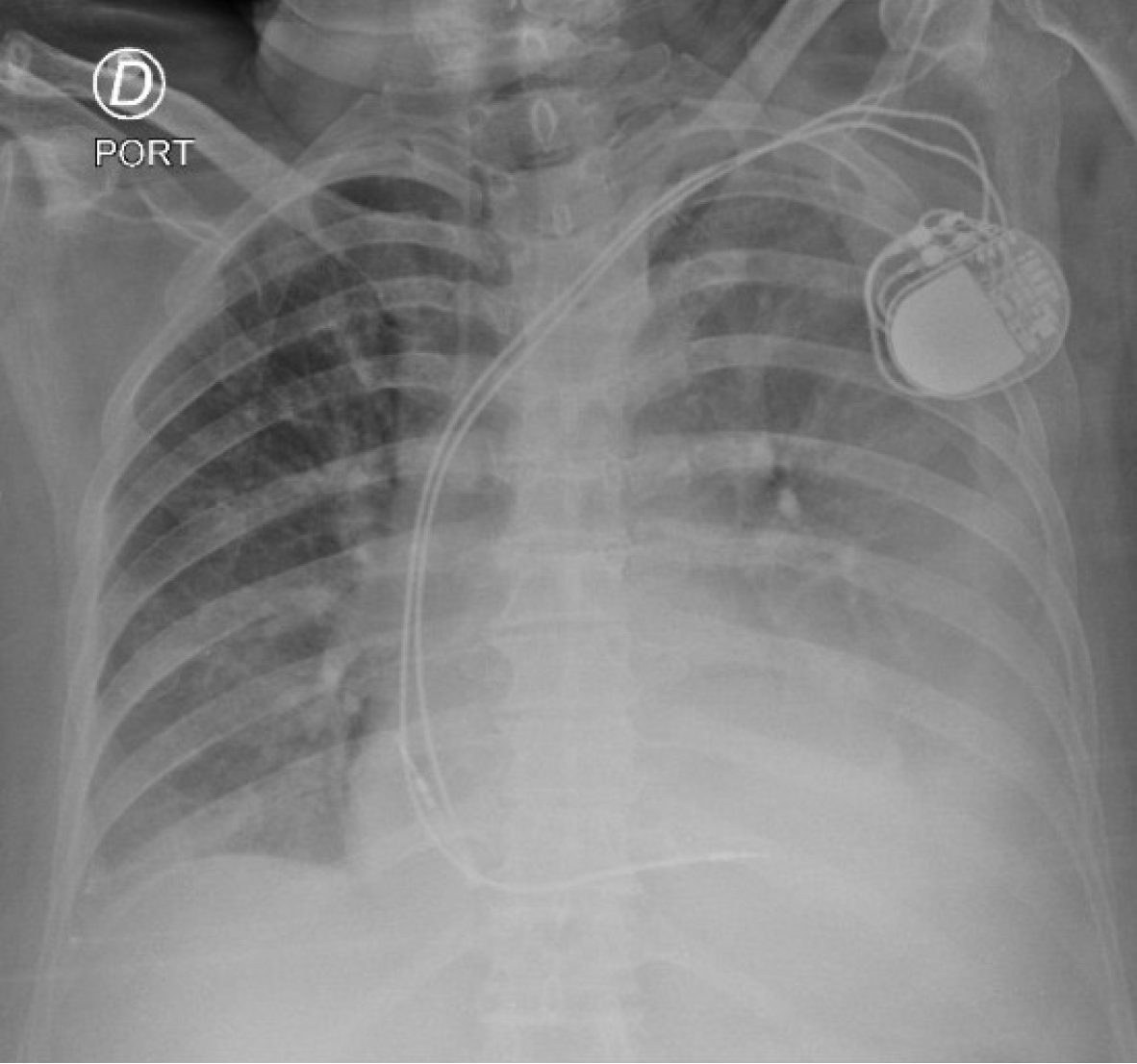

The patient received four vials of polyvalent antivenom serum, fresh frozen plasma transfusion, and intensive care unit monitoring. Due to persistent bradycardia and atrioventricular block, a transvenous pacemaker was placed followed by permanent pacemaker implantation before discharge (Figure 3).

Upon reviewing the medical history from the reference hospital, it was concluded that the patient's pacemaker was functioning properly. No new cardiac episodes were reported. At of the writing of this case report, the patient had remained asymptomatic.

We present herein the case of an elderly female who experienced envenomation caused by a Bothrops snake. While receiving treatment, sinus bradycardia and QTc prolongation were identified. These cardiac complications developed into severe arrhythmias that required the implantation of a permanent pacemaker. Although rare, this presentation adds to a limited but growing body of evidence on cardiac electrophysiological complications secondary to Bothrops envenomation. Cases with similar arrhythmic patterns, such as ventricular tachycardia and atrioventricular blocks, have been reported in patients without prior cardiovascular disease, supporting the possibility of venom-induced conduction system injury[16,17].

Bothrops, Bothriopsis, Bothriechis, and Bothrocophias are genera of snakes most likely to cause ophidian envenomation. In Colombia the herpetofauna include a great diversity of venomous snakes, with the Viperidae and Elapidae families being the most medically relevant. The species with the greatest impact in the country are B. asper, B. atrox, B. bilineatus, and Crotalus durissus[5]. Although the venom of these species are not identical, they generate a similar clinical response characterized by a histotoxic-hemorrhagic-hypotensive syndrome, which can lead to the death if not treated in a timely manner[18].

Symptoms of Bothrops envenomation usually begin within the first 10-20 minutes after the bite, with localized edema at the affected site. As time passes, a progressive clinical picture develops, including severe pain, firm edema, and erythema with pinkish or cyanotic patches. In severe cases the patient may experience a significant decrease in blood pressure, alterations in coagulation tests, spontaneous hemorrhages, and tissue necrosis, which may evolve into severe complications such as shock and multiorgan failure[18].

The mechanisms of these manifestations, both local and systemic, are related to the direct effects of toxins present in the snake venom. Among these are metalloproteinases, serine proteinases, phospholipase A2, lectin C-type toxins, integrin antagonists, and secretion proteins rich in cysteine and L-amino acid oxidases. The clinical course may vary depending on the Bothrops species and the amount of venom[14]. Although the patient’s symptoms and course were compatible with a bothropic accident, the species responsible for the bite could not be identified with certainty.

Initially, this case was classified as a mild Bothrops envenomation. Six hours after the bite, the patient’s reaction was limited to localized edema without systemic involvement or significant alterations in laboratory tests. However, there were subsequent alterations in coagulation tests, and unexpected cardiovascular findings such as asymptomatic sinus bradycardia and QTc prolongation prompted further evaluation. Direct alterations in cardiac electrophysiology due to bothropic accidents have not been documented. However, the literature describes exceptional cardiovascular manifestations. Cases of heart failure[13,14], cardiomyopathy[13,19,20], and cardiac arrhythmias have been reported in other genera of the Viperidae[20-23], highlighting the need for further research on the cardiovascular effects of these snakebite envenomings. A review by Averin and Utkin[24] emphasized that certain venom-derived peptides, such as bradykinin-potentiating peptides and phospholipase A2, have the potential to cause direct cardiotoxic effects by altering vascular tone, membrane stability, and intracellular calcium handling.

Specific electrophysiological alterations as well as coronary and myocardial involvement are not yet fully understood. Several mechanisms have been identified to explain these complications. Direct damage to myocardial cell membranes may lead to myocarditis. There is evidence of toxin-induced arrhythmias and hypercoagulable states predisposing patients to coronary thrombosis. Coronary vasospasm due to direct toxic effects and inflammatory processes related to hypersensitivity to the poison have also been identified. Likewise, acute renal insufficiency may contribute to severe hyperkalemia that exacerbates cardiovascular alterations[14,22,25]. In particular cardiotoxins, hemorrhagic factors, and vasoactive peptides found in Viperidae venom may act synergistically to induce hypotension, arrhythmias, or myocardial dysfunction through a combination of vasodilation, endothelial disruption, and neurohumoral imbalance[16].

In addition, the venom of snakes of the Viperidae family contains proteins that activate factors V and X, thereby altering the balance between coagulation and anticoagulation[14,26]. Although these alterations typically do not generate thrombosis in humans following subcutaneous or intramuscular administration of the venom, the injection of large volumes with high intravascular penetration significantly increases the risk of thrombosis in the coronary, cerebral, and pulmonary vessels[14].

Recent studies have explored Bothrops venom-induced cardiotoxicity. In experiments on human cardiac tissue, B. lanceolatus venom has been shown to affect mitochondrial function by reducing the efficiency of oxidative phos

Furthermore, Sartim et al[30] evaluated markers of myocardial damage in patients with B. atrox envenomation. They found elevated troponin I and FABP3 levels in a significant proportion of patients and suggested an association with venom-induced coagulopathy. Myocardial injury may occur even in the absence of overt clinical manifestations and may be underdiagnosed in bothropic accidents.

Phospholipase A2 is present in the venom of Bothrops snakes. It can produce cardiotoxicity by inducing damage to cell membranes and altering intracellular calcium regulation[22,24]. These toxins cause bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and myocardial contractures and contribute to cardiac alterations observed in this type of poisoning[24].

Although no long-term follow-up data were available for the present case, published reports suggest that patients with venom-induced cardiac complications, including arrhythmias and myocarditis, experience favorable outcomes following timely intervention. In the case series by Florentin et al[29], both patients recovered fully with no neurological or cardiological sequelae after cardiac MRI-confirmed myocarditis due to B. lanceolatus envenomation. Similarly, Virmani[17] described the resolution of rhythm disturbances within 48 hours in a patient with transient echocardiogram abnormalities after envenomation. These findings underscore the potential for reversibility in venom-related cardiac injury and highlight the importance of early detection and management.

There were several limitations inherent to the management of toxicological emergencies in rural areas, including the lack of specific identification of the Bothrops species involved and the absence of previous studies of the patient’s baseline cardiovascular status. Moreover, no long-term follow-up was available to assess the persistence or resolution of cardiac conduction abnormalities after discharge. The available literature on specific cardiovascular alterations related to bothropic envenomation is limited and further investigation is required. Despite these limitations, this case highlighted the importance of a multidisciplinary approach and continuous cardiovascular monitoring in patients with Bothrops envenomation, particularly in those with atypical clinical findings.

Although a definitive causal relationship between Bothrops envenomation and cardiac alterations observed in this patient cannot be conclusively established, this case underscored the potential for serious cardiovascular complications even when the initial envenomation is mild. It highlighted the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and ensuring close cardiovascular monitoring in patients with Bothrops bites. This is particularly relevant given the variability in venom composition and individual susceptibility. Advancing research into the pathophysiological mechanisms of venom-induced cardiotoxicity remains essential to improve early detection, guide monitoring protocols, and optimize therapeutic strategies to prevent adverse outcomes.

| 1. | Instituto Nacional de Salud. 1.546 accidentes ofídicos han sido reportados en 2024 en el país. 2024. [cited 7 March 2025]. Available from: www.ins.gov.co/Noticias/Paginas/1.546-accidentes-ofídicos-han-sido-reportados-en-2024-en-el-país.aspx#:~:text=Según%20cifras%20del%20INS%2C%20en,1.529%20ocurrieron%20en%20territorio%20colombiano. |

| 2. | Instituto Nacional de Salud. Informe de evento. Accidente Ofídico. Periodo epidemiológico 06 2024. [cited 7 March 2025]. Available from: www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/Informesdeevento/ACCIDENTE%20OFÍDICO%20PE%20VI%202024.pdf. |

| 3. | Sevilla-Sánchez MJ, Mora-Obando D, Calderón JJ, Guerrero-Vargas JA, Ayerbe-González S. Snakebite in the department of Nariño, Colombia: a retrospective analysis, 2008-2017. Biomedica. 2019;39:715-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Estrada-Gómez S, Vargas-Muñoz LJ, Higuita-Gutiérrez LF. Epidemiology of Snake Bites Linked with the Antivenoms Production in Colombia 2008-2020: Produced Vials Do Not Meet the Needs. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2022;14:171-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Otero-Patiño R. Snake Bites in Colombia. In: Vogel CW, Seifert S, Tambourgi D, editors. Clinical Toxinology in Australia, Europe, and Americas. Berlin: Springer, 2018: 3-50. |

| 6. | Gutiérrez JM, Calvete JJ, Habib AG, Harrison RA, Williams DJ, Warrell DA. Snakebite envenoming. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 78.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Harrison RA, Hargreaves A, Wagstaff SC, Faragher B, Lalloo DG. Snake envenoming: a disease of poverty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | León-Núñez LJ, Camero-Ramos G, Gutiérrez JM. Epidemiology of snakebites in Colombia (2008-2016). Rev Salud Publica (Bogota). 2020;22:280-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | World Health Organization. Snakebite envenoming: a strategy for prevention and control. 2019. [cited 7 March 2025]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/324838. |

| 10. | Chippaux JP. Snakebite envenomation turns again into a neglected tropical disease! J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2017;23:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gutiérrez JM. Reducing the impact of snakebite envenoming in Latin America and the Caribbean: achievements and challenges ahead. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:530-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Isbister GK, Brown SG, Page CB, McCoubrie DL, Greene SL, Buckley NA. Snakebite in Australia: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Med J Aust. 2013;199:763-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chara K, Baccouche N, Turki O, Regaig K, Chaari A, Bahloul M, Bouaziz M. A rare complication of viper envenomation: cardiac failure. A case report. Med Sante Trop. 2017;27:52-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Restrepo Bastidas AA, Aguirre-Flórez M, Hoyos Muñoz JA, Gonzales Ramírez M, Echeverry Piedrahita DR. Heart failure secondary to a snake bite. The intensivist's vision: Case Report. Rev Fac Med Humana. 2024;24:158-162. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Sano-Martins IS, Fan HW, Castro SC, Tomy SC, Franca FO, Jorge MT, Kamiguti AS, Warrell DA, Theakston RD. Reliability of the simple 20 minute whole blood clotting test (WBCT20) as an indicator of low plasma fibrinogen concentration in patients envenomed by Bothrops snakes. Butantan Institute Antivenom Study Group. Toxicon. 1994;32:1045-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | C. , Kanattu PS. A Study of Cardiac Profile in Patients with Snake Envenomation and Its Complications. Int J Clin Med. 2017;08:167-177. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Virmani SK. Cardiac Involvement In Snake Bite. Med J Armed Forces India. 2002;58:156-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Azuara Antonio O, Ortiz MI, Mateos Mauricio FA, Madrigal Anaya JDC, Hernández-ramírez L. Fisiopatología de Accidente Ofídico por Bothrops (Bothrópico). Educación Y Salud Boletín Científico Instituto De Ciencias De La Salud Universidad Autónoma Del Estado De Hidalgo. 2024;12:40-46. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Palomo SA, Medina CM, Carvajal MM, Sandoval M. Envenenamiento ofídico por el género bothrops complicado con miocardiopatía tóxica: a propósito de un caso. CIMEL. 2014;19:1. |

| 20. | Sunil KK, Joseph JK, Joseph S, Varghese AM, Jose MP. Cardiac Involvement in Vasculotoxic and Neurotoxic Snakebite - A not so Uncommon Complication. J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68:39-41. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Virmani S, Bhat R, Rao R, Kapur R, Dsouza S. Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation due to Venomous Snake Bite. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:OD01-OD02. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liblik K, Byun J, Saldarriaga C, Perez GE, Lopez-Santi R, Wyss FQ, Liprandi AS, Martinez-Sellés M, Farina JM, Mendoza I, Burgos LM, Baranchuk A; Neglected Tropical Diseases and other Infectious Diseases affecting the Heart (the NET-Heart project). Snakebite Envenomation and Heart: Systematic Review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022;47:100861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Agarwal A, Kumar T, Ravindranath KS, Bhat P, Manjunath CN, Agarwal N. Sinus node dysfunction complicating viper bite. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2015;23:212-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Averin AS, Utkin YN. Cardiovascular Effects of Snake Toxins: Cardiotoxicity and Cardioprotection. Acta Naturae. 2021;13:4-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Monteiro WM, Contreras-Bernal JC, Bisneto PF, Sachett J, Mendonça da Silva I, Lacerda M, Guimarães da Costa A, Val F, Brasileiro L, Sartim MA, Silva-de-Oliveira S, Bernarde PS, Kaefer IL, Grazziotin FG, Wen FH, Moura-da-Silva AM. Bothrops atrox, the most important snake involved in human envenomings in the amazon: How venomics contributes to the knowledge of snake biology and clinical toxinology. Toxicon X. 2020;6:100037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sarmiento K, Torres I, Guerra M, Ríos C, Zapata C, Suárez F. Epidemiological characterization of ophidian accidents in a Colombian tertiary referral hospital. Retrospective study 2004-2014. Rev Fac Med. 2018;66:153-158. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cano-Sanchez M, Ben-Hassen K, Louis OP, Dantin F, Gueye P, Roques F, Mehdaoui H, Resiere D, Neviere R. Bothrops lanceolatus snake venom impairs mitochondrial respiration and induces DNA release in human heart preparation. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:e0010523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rodrigues MA, Dias L, Rennó AL, Sousa NC, Smaal A, da Silva DA, Hyslop S. Rat atrial responses to Bothrops jararacussu (jararacuçu) snake venom. Toxicology. 2014;323:109-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Florentin J, Farid K, Kallel H, Neviere R, Resiere D. Case Report: Acute myocarditis and cerebral infarction following Bothrops lanceolatus envenomation in Martinique: a case series. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1421911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sartim MA, Raimunda da Costa M, Bentes KO, Mwangi VI, Pinto TS, Oliveira S, Mota Cordeiro JS, Wilson do Nascimento Corrêa J, Ferreira JMBB, Cardoso de Melo G, Sachett J, Monteiro WM. Myocardial injury and its association with venom-induced coagulopathy following Bothrops atrox snakebite envenomation. Toxicon. 2025;258:108312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |