Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.104000

Revised: January 27, 2025

Accepted: February 21, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 105 Days and 0.7 Hours

Up to one-third of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have an indication for oral anticoagulation (OAC), primarily due to underlying atrial fibrillation. The optimal approach concerning periprocedural continuation vs interruption of OAC in patients undergoing TAVR remains uncertain, which our meta-analysis aims to address.

To explore safety and efficacy outcomes for patients undergoing TAVR, comparing periprocedural continuation vs interruption of OAC therapy.

A literature search was conducted across major databases to retrieve eligible studies that assessed the safety and effectiveness of TAVR with periprocedural continuous vs interrupted OAC. Data were pooled using a random-effects model with risk ratio (RR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI) as effect measures. All statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Four studies were included, encompassing a total of 1813 patients with a mean age of 80.6 years and 49.8% males. A total of 733 patients underwent OAC interruption and 1080 continued. Stroke incidence was significantly lower in the OAC continuation group (RR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.40-0.94; P = 0.03). No significant differences in major vascular complications were found between the two groups (RR = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.77-1.16; P = 0.60) and major bleeding (RR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.72-1.12; P = 0.33). All-cause mortality was non-significant between the two groups (RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.57-1.20; P = 0.32).

Continuation of OAC significantly reduced stroke risk, whereas it showed trends toward lower bleeding and mortality that were not statistically significant. Further large-scale studies are crucial to determine clinical significance.

Core Tip: Periprocedural continuation of oral anticoagulation (OAC) in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) significantly reduces stroke risk (risk ratio = 0.62, P = 0.03) without increasing the incidence of major bleeding or vascular complications. Although no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality was observed, the results suggest a favorable safety and efficacy profile for OAC continuation. These findings underscore the need for further large-scale, randomized trials to establish definitive guidelines for periprocedural anticoagulation management in patients undergoing TAVR.

- Citation: Goyal A, Shoaib A, Fareed A, Jawed S, Khan MT, Salim N, Zameer U, Siddiqui A, Thakur T, Sulaiman SA. Outcomes of periprocedural continuation vs interruption of oral anticoagulation in transcatheter aortic valve replacement. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(3): 104000

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i3/104000.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.104000

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is a widely accepted treatment in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (AS) regardless of surgical risk[1,2]. Patients with AS experience a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) due to the resultant pressure overload in the left heart chambers[3] due to AF, about 33% of patients undergoing TAVR need long-term anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolic events and bleeding complications[4-6].

According to the 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide and the 2022 American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline, interrupting oral anticoagulation (OAC) in patients undergoing interventions with a high risk of bleeding is recommended[7,8]. However, prior published observational studies on this topic, which had small sample sizes, have suggested that the continuation of OAC is associated with a lower incidence of periprocedural stroke[9,10]. By contrast, a recent trial: The Periprocedural Continuation vs Interruption of Oral Anticoagulant Drugs during Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (POPular PAUSE TAVI), which included 858 participants, revealed that patients in the interruption group were associated with significantly lower rates of major bleeding compared to those participants in the periprocedural continuation group[11].

Therefore an appropriate OAC strategy for patients undergoing TAVR has shown conflicting results.

This study followed the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines[12]. Our protocol was registered with PROSPERO, The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews with registration No. CRD42024597411.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Clinical trials.gov, and Cochrane Library databases until September 2024 to identify relevant studies. We created search strings using boolean operators

The inclusion criteria for the studies followed the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome framework which is commonly applied in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Following this framework, ‘P’ refers to the adult patients (18-72 years old) on OAC therapy (either vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) or direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs]) who underwent TAVR, ‘I’ refers to the continuation of OAC therapy throughout the procedure, ‘C’ refers to the interruption of OAC therapy 2-4 days before the procedure, and ‘O’ includes the incidence of stroke as the primary outcome, while major vascular complications, major bleeding, and mortality as secondary outcomes. Thus the detailed inclusion criteria consisted of: (1) Studies involving patients on OAC therapy who underwent TAVR; (2) Studies comparing OAC continuation with interruption in these patients; and (3) Studies reporting any of the outcomes of interest.

Exclusion criteria consisted of single-arm studies, clinical trials with unavailable results, review articles, nonhuman studies, case reports, case series, editorials, abstracts, reviews, comments, letters, expert opinions, studies lacking original data, and duplicate publications.

The literature search results were imported into EndNote X9 software (Clarivate Analytics, Alexandria, VA, United States), where duplicates were removed. Two authors (Khan MT and Salim N) independently screened the studies by evaluating the titles and abstracts, followed by a thorough review of the full-text articles. In cases of disagreement, a third author (Fareed A) was consulted for resolution. The article with the highest relevance or the largest sample size was selected in cases with overlapping populations. Data extraction was also performed by two authors (Khan MT and Salim N) using a pre-tested Excel sheet and including the study details such as first author, publication year, country, sample size, study type, and baseline characteristics of participants. Any discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third author (Goyal A).

We evaluated randomized clinical trials (RCTs) using the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool 2.0[13]. Five components were assessed: (1) Random sequence generation; (2) Blinding of participants and personnel; (3) Blinding of outcome assessment; (4) Incomplete outcome data; and (5) Selective reporting. Each item was scored as low, unclear, or high risk of bias. For the observational studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for quality assessment was utilized[14]. The studies were stratified according to their quality ratings based on the total score. “High” quality was defined as a score of 6-9, “moderate” quality as a score of 3-5, and “low” quality as a score of 2 or less.

We conducted statistical analyses using Review Manager (version 5.4). Pooled risk ratio (RR) with their 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for dichotomous variables using the Mantel-Haenszel random effects model, and the results were illustrated through forest plots. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. To assess the potential heterogeneity among studies, Higgins I2 statistics were used[15], with values classified as low (< 25%), moderate (25%-75%), or high (> 75%). An additional subgroup analysis was performed for RCTs and observational studies. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots.

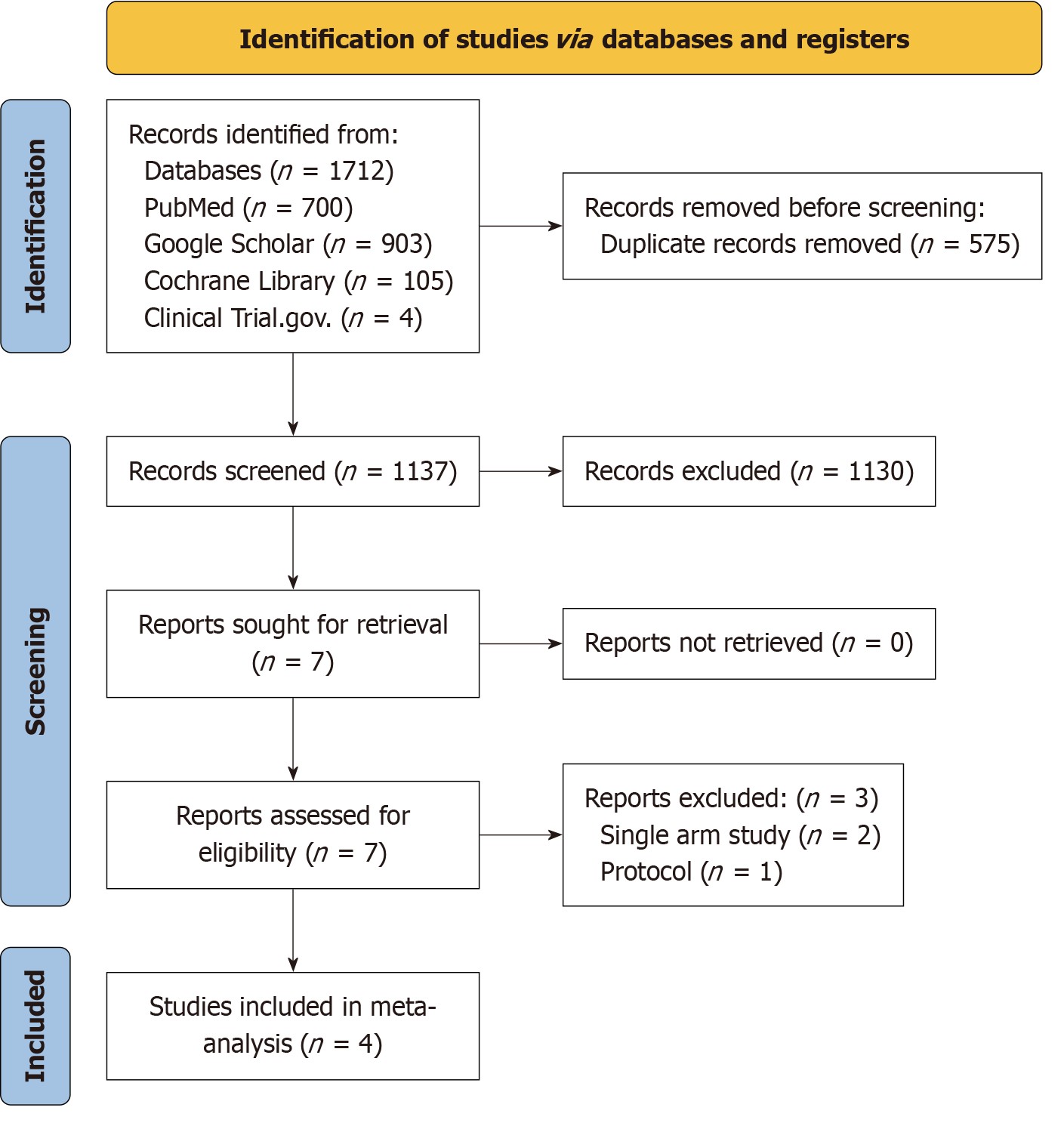

In an initial literature search, 1712 articles were identified. After exclusions, four studies[9-11,16] were deemed appropriate for inclusion in this meta-analysis. The detailed steps of literature search and study selection are shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Among the four studies included, three were observational and one was an RCT. The pooled population across the studies examining the effects of interrupting or continuing OAC consisted of 1813 patients, including 733 patients receiving OAC interruption and 1080 patients receiving OAC continuation. The overall mean age of the population was approximately 80.6 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.7). All of the studies were conducted in Europe. Male patients constituted approximately 49.8% of the overall population pooled. The detailed study and baseline characteristics of the included studies are presented in Supplementary Table 2 and Table 1, respectively[9-11,16].

| Intervention | Mangner et al[16], 2019 | Brinkert et al[10], 2019 | Brinkert et al[9], 2021 | van Ginkel et al[11], 2025 | ||||

| Interruption of OAC (n = 299) | Continuation of OAC (n = 299) | Interruption of OAC (n = 185) | Continuation of OAC (n = 186) | Interruption of OAC (n = 733) | Continuation of OAC (n = 584) | Interruption of OAC (n = 427) | Continuation of OAC (n = 431) | |

| Interruption period | NA | 48-96 hours prior to TAVR | 48-96 hours prior to TAVR | DOACs: 48 hours prior to TAVR, except for those with glomerular filtration rate 50-80 mL/minute per 1.73 m3 and 30-50 mL/minute per 1.73 m3 on Dabigatran, who stopped 72 hours and 96 hours prior, respectively | ||||

| Acenocoumarol 72 hours prior | ||||||||

| Phenprocoumon or warfarin 120 hours prior | ||||||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 80 (76-83) | 80 (77-84) | NA | NA | 82 (78–86) | 82 (78–85) | 80.9 (SD = 6.2) | 81.4 ± 5.6 |

| Male | 127 (42.5) | 135 (45.2) | NA | NA | 351 (48) | 297 (51) | 289 (68) | 273 (63) |

| Median body-mass index | 27.9 (25.0-32.0) | 27.7 (24.5-31.5) | NA | NA | 27.1 (24.0–30.8) | 27.1 (24.0–30.8) | 26.9 (IQR = 24.3–30.8) | 26.5 (IQR = 24.2–29.7) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 299 (100) | 299 (100) | 95% of total sample size | 95% of total sample size | 644 (94) | 500 (97) | 406 (95.1) | 414 (96.1) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 6 (5-6) | 5 (5-6) | 5.1 (SD = 1.5) | 5.1 (SD = 1.5) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 4.4 (SD = 1.4) | 4.5 ± 1.4 |

| Hypertension | 289 (96.7) | 291 (97.3) | NA | NA | 664 (91) | 525 (90) | 322 (75.4) | 339 (78.7) |

| Previous coronary artery disease | 131 (43.8) | 126 (42.3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 206 (48.2) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 162 (54.2) | 126 (42.3) | NA | NA | 277 (38) | 204 (35) | 206 (48.2) | 207 (48.0) |

| Previous cerebrovascular incident | 39 (13.0) | 48 (16.1) | 45 (24) | 26 (14) | 118 (16) | 90 (15) | 101 (24) | 88 (20) |

| Peripheral arterial vascular disease | NA | NA | NA | NA | 88 (12) | 75 (13) | 85 (19.9) | 79 (18.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 47 (15.7) | 47 (15.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 221 (51.8) | 213 (49.4) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 101 (33.9) | 95 (32.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 49 (11.5) | 68 (15.8) |

| Previous pacemaker implantation | NA | NA | NA | NA | 101 (14) | 114 (20) | 88 (20.6) | 75 (17.4) |

| Type of anticoagulation | VKA: 299 (100) | VKA: 117 (39). DOACs: 182 (61) | VKA: 100 (54). DOACs: 85 (46) | VKA: 131 (70). DOACs: 55 (30) | VKA: 511 (70). DOACs: 222 (30) | VKA: 294 (50). DOACs: 290 (50) | Multicentric study, with variations among different trial sites | Multicentric study, with variations among different trial sites |

The included RCT was found to have a “low” risk of bias, in addition to all of the observational studies being rated as “good” quality. A detailed evaluation is presented in Supplementary Table 3[9,10,16] and Supplementary Figure 1[11]. Visual inspection of funnel plots showed a low risk of publication bias, as presented in Figure 2[9-11,16].

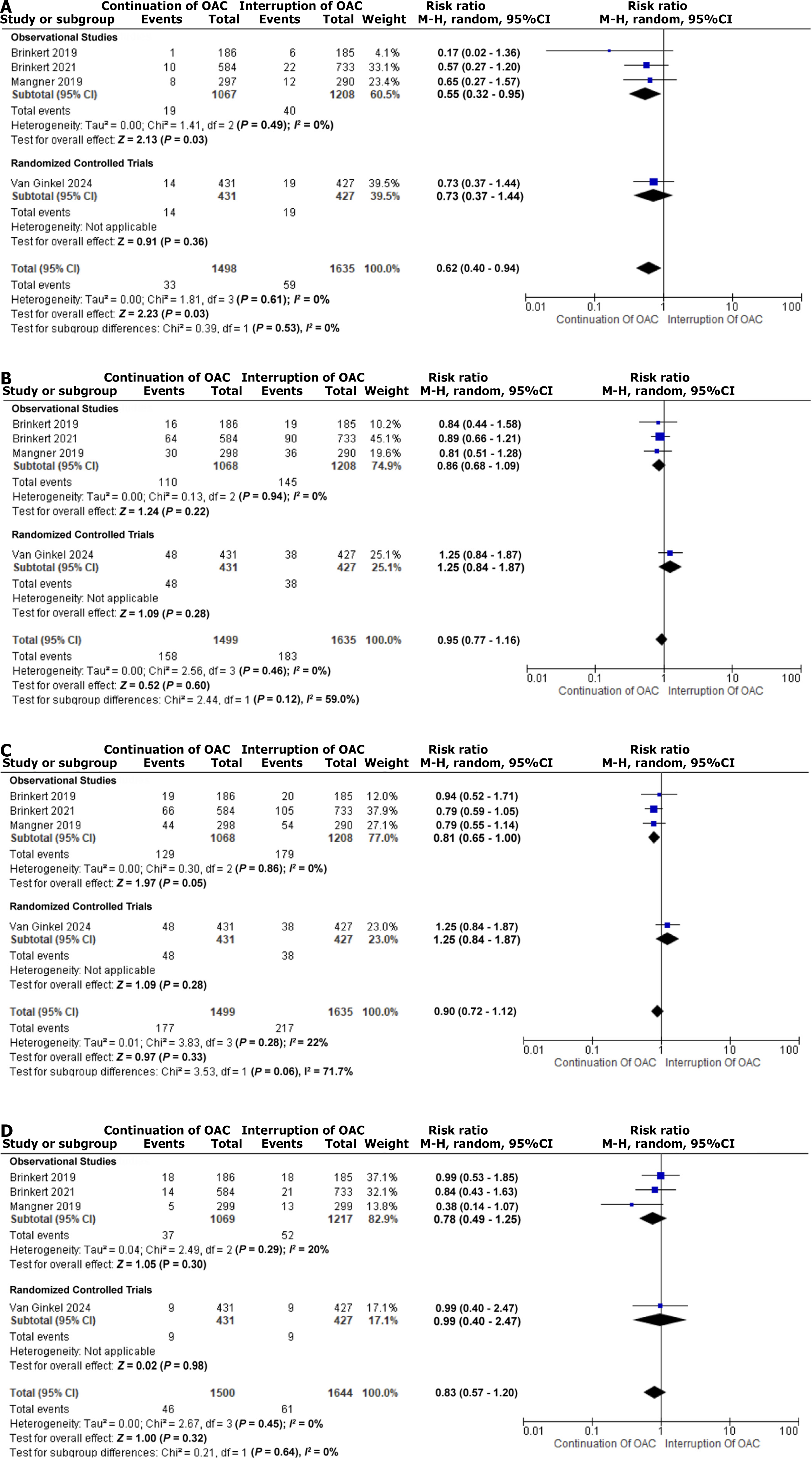

The pooled analysis of the four included studies demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of stroke in the OAC continuation group compared to the OAC interruption group (RR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.40-0.94; P = 0.03), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). This significant reduction was also observed in the subgroup analysis of observational studies (RR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.32-0.95; P = 0.03; I2 = 0%). By contrast, the included RCT showed a non-significant difference in stroke incidence (RR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.37-1.44). The pooled and subgroup analyses of stroke incidence are presented in Figure 2A[9-11,16].

The incidence of major vascular complications was similar between the OAC continuation and OAC interruption groups, with non-significant results (RR = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.77-1.16; P = 0.60) and zero heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), as shown in Figure 2B[9-11,16]. A pooled analysis of four studies also demonstrated that the incidence of major bleeding was comparable between the two groups (RR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.72-1.12; P = 0.33), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 22%) as presented in Figure 2C[9-11,16]. Similarly, the outcome of all-cause mortality revealed non-significant differences between the OAC continuation and interruption groups (RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.57-1.20; P = 0.32), with zero heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), as illustrated in Figure 2D[9-11,16].

The current meta-analysis involving 1813 patients undergoing TAVR demonstrates that compared to patients who interrupted their anticoagulant medication, those who continued OAC during the procedure were associated with a significantly decreased incidence of stroke events (P = 0.03), with no increased risk of major vascular or bleeding events. The risk of mortality was comparable between the two groups. These findings indicate that continued OAC may be used in patients undergoing TAVR who have an increased risk of stroke occurrence, particularly those with a prior history of stroke or AF, high CHA2DS2-VASc scores, and are at high risk for thromboembolism such as patients with mitral stenosis and prosthetic valves.

TAVR has revolutionized the management of severe AS irrespective of surgical risk. While overall outcomes have improved, a notable subset of patients derive limited benefit from the intervention[17-19]. Despite patient variables such as comorbidities, frailty, and advanced age[17,19] as well as the psychological and demographic factors playing a significant role in the unfavorable outcomes following TAVR, complications are likely to hinder the period of recovery. Nevertheless, current research consistently shows that periprocedural complications can arise, influencing survival outcomes following TAVR to varying degrees, with bleeding and thromboembolic events remaining common occurrences[20-22]. In this setting, the management of periprocedural anticoagulation is critical to mitigate these complications. Thus, the perioperative management of OAC represents a significant concern in the context of an improved TAVR strategy designed to enhance rapid recovery and lessen procedural difficulties[23]. Approximately one-third of patients receiving TAVR for the treatment of severe AS have an indication of OAC[24-27]. In these cases, OAC with a VKA or a DOAC is indicated. The debate surrounding the management of OAC during TAVR persists, with studies investigating the merits of continued vs periprocedural interruption of OAC yielding inconsistent conclusions[9-11,16].

Given the conflicting outcomes in the observational studies and the RCT, the current meta-analysis intended to eliminate this uncertainty by pooling the results to offer a robust analysis of the results in this patient group. In comparison to the interruption of OAC, this meta-analysis demonstrates that continuing OAC therapy is associated with a lower risk of stroke without raising the risk of major vascular complications, severe bleeding, or all-cause death. This result aligns with previous observational studies[9,10,16]. However, the current Popular Pause TAVI trial did not reciprocate the same result[11]. The fact that the POPULAR PAUSE TAVI study was not intended to evaluate the advantages of continued OAC concerning thromboembolic events could account for some of the contradictory results and thus, the results should not be taken as definitive evidence, but rather as a stimulus for ongoing research into the nuanced interactions between OAC continuation or interruption and clinical outcomes in TAVR. Future RCTs aimed at a larger population should prioritize thromboembolic event reduction as a primary endpoint to clarify the optimal OAC management strategy for patients with TAVR. Our results, which highlight the advantages of continued OAC, are consistent with RCTs evaluating the safety and effectiveness of continued OAC in patients from various demographic backgrounds. The Role of Coumadin in Preventing Thromboembolism in AF Patients Undergoing Catheter Ablation (COMPARE) trial, which included 1584 patients with AF revealed that maintaining warfarin therapy after catheter ablation for AF was linked to a decreased risk of stroke and mild hemorrhage compared to stopping warfarin therapy and bridging with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin[28]. Similarly, in the Randomized Evaluation of Dabigatran Etexilate Compared to Warfarin in Pulmonary Vein Ablation: Assessment of an Uninterrupted Periprocedural Anticoagulation Strategy (RECRUIT) trial with 704 patients, Calkins et al[29] demonstrated that continued dabigatran use was linked to fewer bleeding problems than continued warfarin use in patients undergoing ablation for AF. Furthermore, the What is the Optimal Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapy in Patients with OAC and Coronary Stenting trial, which included 573 patients undergoing coronary angiography, concluded that continued OAC was safe and not associated with an increased risk of bleeding or major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events[30]. Given that our results are primarily derived from observational studies that are subject to bias, they should be viewed as hypothesis-generating and these results warrant rigorous validation through RCTs to account for potential confounders, confirm observed associations, and guide clinical decision-making.

There is still a great deal of uncertainty around the administration of OAC in patients having TAVR, mostly because there is a dearth of strong data from RCTs. Clinical protocols vary greatly throughout institutions; some choose to discontinue anticoagulation for variable periods, while others continue it for the entire process. The type of anticoagulant being used affects these strategies; while DOACs have a rapid onset and known pharmacokinetics that make short-term control easier, they are frequently stopped over a brief period. Conversely, due to their longer half-lives and the availability of reversal agents, which are more readily available for VKAs than for DOACs in many clinical settings, VKAs tend to be prolonged[10,31]. Furthermore, past research on the treatment of OAC in patients with TAVR did not fairly depict actual interruption or continuation techniques[10]. Heparin bridging was given to a significant number of patients in the interruption groups; however, this procedure does not entirely stop anticoagulant medication and raises the risk of bleeding. Moreover, continuation tactics often featured short-term breaks rather than actual therapeutic continuity. This disparity highlights the need for more accurate assessments of OAC control during TAVR procedures and raises questions about how these techniques can be classified. Such assessments are necessary to more accurately evaluate the safety and effectiveness of various anticoagulation methods in this patient population.

This meta-analysis is the first to compare patient outcomes regarding continuation vs interruption of OAC during the periprocedural period in TAVR candidates. The credibility of our conclusions is strengthened by the strong quality ratings and overall low risk of bias across the studies. Moreover, the consistent outcomes of our research in various contexts are reinforced by the low heterogeneity identified (I2 = 0% for stroke).

Future studies should include a larger sample size to enhance the precision of clinical event rate estimates. Subsequent investigations should focus on identifying patient-specific factors that may affect the delivery of anticoagulation, such as distinct risk profiles and concurrent medical conditions. Analyzing these details can aid in developing tailored strategies that improve outcomes and patient safety for this vulnerable population. Researchers should focus on specific patient populations that would benefit most from continued usage of OACs in addition to plausible explanations for observed differences in thromboembolic and bleeding risks. A comprehensive surveillance research study is required to determine if the benefits of continuous vs interrupted OAC therapy endure after the peri-procedural interval. Understanding the long-term impact on thromboembolic events, bleeding complications, and mortality is important. Subgroup analysis could be useful in future meta-analyses to pinpoint particular populations (such as individuals with high-risk AF) that may benefit more from either strategy. This could be useful for tailored anticoagulant regimens.

The results of this analysis should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, the meta-analysis may be underpowered, with the sample size potentially insufficient to detect statistically significant differences for many outcomes, which likely contributed to the non-significant findings. Second, in the future, collaborating with multiple centers around the globe to conduct studies with larger and more diverse populations is important, as including patients from various geographical locations, healthcare systems, and analyzing variations in demographic and clinical characteristics could offer more comprehensive results. This also includes expanding studies to analyze specific groups according to their CHA2DS2-VASc scores, type of OAC, and comorbidities as well as long-term outcomes including mortality, thromboembolism, and bleeding events, which are of clinical relevance in the management of patients. Third, only four studies were included, limiting the generalizability of the results and increasing the risk of random error. Additionally, there were differences in the definition of interrupted anticoagulation and the outcome measures (stroke, vascular complications major, and bleeding) across studies. For instance, Brinkert et al[10] have reported that anticoagulation was interrupted 48-96 hours prior to TAVI while van Ginkel[11] have reported that oral anticoagulants were interrupted 48 hours prior to TAVI except for patients with glomerular filtration rate 50-80 mL/minute per 1.73 m3 and 30-50 mL/minute per 1.73 m3 on dabigatran, who stopped 72 hours and 96 hours prior, respectively. They also reported that VKA acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon or warfarin were interrupted 72 hours and 120 hours before TAVI, respectively[11]. This warrants further prospective research with standardized definitions. Fourth, despite including RCTs to minimize bias and confounding, most of the included studies were observational, which have an inherent risk for confounding bias. Fifth, several studies lacked details on the type of anticoagulation used and the presence of AF, both of which are crucial for interpreting the results, particularly in high-risk populations. Future research could address this gap by conducting larger, longer trials that specifically evaluate different types of anticoagulation within subgroup analyses, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of their impact across diverse patient groups. Lastly, all the studies were conducted in Europe, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other geographic regions or healthcare settings.

Compared to periprocedural interruption of OAC, the continuation of OAC during TAVR was associated with a significantly decreased incidence of stroke events without compromising patient safety in terms of major vascular complications, major bleeding, or death. Our findings emphasize the need for shared decision-making regarding the optimal OAC therapy for this patient population. Future large-scale and well-powered RCTs are warranted to validate these findings and guide clinical decision-making.

| 1. | Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Kodali SK, Thourani VH, Tuzcu EM, Miller DC, Herrmann HC, Doshi D, Cohen DJ, Pichard AD, Kapadia S, Dewey T, Babaliaros V, Szeto WY, Williams MR, Kereiakes D, Zajarias A, Greason KL, Whisenant BK, Hodson RW, Moses JW, Trento A, Brown DL, Fearon WF, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Jaber WA, Anderson WN, Alu MC, Webb JG; PARTNER 2 Investigators. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3232] [Cited by in RCA: 3819] [Article Influence: 424.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Williams M, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Babaliaros V, Thourani VH, Corso P, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock SJ; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187-2198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4547] [Cited by in RCA: 4933] [Article Influence: 352.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Steine K, Rossebø AB, Stugaard M, Pedersen TR. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in asymptomatic patients with moderate aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:897-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sannino A, Gargiulo G, Schiattarella GG, Perrino C, Stabile E, Losi MA, Galderisi M, Izzo R, de Simone G, Trimarco B, Esposito G. A meta-analysis of the impact of pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:e1047-e1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tarantini G, Mojoli M, Urena M, Vahanian A. Atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: epidemiology, timing, predictors, and outcome. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1285-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Nieuwkerk AC, Aarts HM, Hemelrijk KI, Cantón T, Tchétché D, de Brito FS Jr, Barbanti M, Kornowski R, Latib A, D'Onofrio A, Ribichini F, Maneiro Melón N, Dumonteil N, Abizaid A, Sartori S, D'Errigo P, Tarantini G, Fabroni M, Orvin K, Pagnesi M, Vicaino Arellano M, Dangas G, Mehran R, Voskuil M, Delewi R. Bleeding in Patients Undergoing Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Incidence, Trends, Clinical Outcomes, and Predictors. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:2951-2962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Murad MH, Arcelus JI, Dager WE, Dunn AS, Fargo RA, Levy JH, Samama CM, Shah SH, Sherwood MW, Tafur AJ, Tang LV, Moores LK. Perioperative Management of Antithrombotic Therapy: An American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Chest. 2022;162:e207-e243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, Albaladejo P, Antz M, Desteghe L, Haeusler KG, Oldgren J, Reinecke H, Roldan-Schilling V, Rowell N, Sinnaeve P, Collins R, Camm AJ, Heidbüchel H; ESC Scientific Document Group. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1330-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1188] [Cited by in RCA: 1370] [Article Influence: 228.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brinkert M, Mangner N, Moriyama N, Keller LS, Hagemeyer D, Crusius L, Lehnick D, Kobza R, Abdel-Wahab M, Laine M, Stortecky S, Pilgrim T, Nietlispach F, Ruschitzka F, Thiele H, Linke A, Toggweiler S. Safety and Efficacy of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement With Continuation of Vitamin K Antagonists or Direct Oral Anticoagulants. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:135-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brinkert M, Keller LS, Moriyama N, Cuculi F, Bossard M, Lehnick D, Kobza R, Laine M, Nietlispach F, Toggweiler S. Safety and Efficacy of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement With Continuation of Oral Anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2004-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Ginkel DJ, Bor WL, Aarts HM, Dubois C, De Backer O, Rooijakkers MJP, Rosseel L, Veenstra L, van der Kley F, van Bergeijk KH, Van Mieghem NM, Agostoni P, Voskuil M, Schotborgh CE, IJsselmuiden AJJ, Van Der Heyden JAS, Hermanides RS, Barbato E, Mylotte D, Fabris E, Frambach P, Dujardin K, Ferdinande B, Peper J, Rensing BJWM, Timmers L, Swaans MJ, Brouwer J, Nijenhuis VJ, Overduin DC, Adriaenssens T, Kobari Y, Vriesendorp PA, Montero-Cabezas JM, El Jattari H, Halim J, Van den Branden BJL, Leonora R, Vanderheyden M, Lauterbach M, Wykrzykowska JJ, van 't Hof AWJ, van Royen N, Tijssen JGP, Delewi R, Ten Berg JM; POPular PAUSE TAVI Investigators; POPular PAUSE TAVI Investigators. Continuation versus Interruption of Oral Anticoagulation during TAVI. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:438-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 40600] [Article Influence: 10150.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 15283] [Article Influence: 2547.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wells GA. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics. 2014. Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. |

| 15. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 25813] [Article Influence: 1122.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mangner N, Crusius L, Haussig S, Woitek FJ, Kiefer P, Stachel G, Leontyev S, Schlotter F, Spindler A, Höllriegel R, Hommel J, Thiele H, Borger MA, Holzhey D, Linke A. Continued Versus Interrupted Oral Anticoagulation During Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation and Impact of Postoperative Anticoagulant Management on Outcome in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:1134-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Arnold SV, Afilalo J, Spertus JA, Tang Y, Baron SJ, Jones PG, Reardon MJ, Yakubov SJ, Adams DH, Cohen DJ; U. S. CoreValve Investigators. Prediction of Poor Outcome After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1868-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Vemulapalli S, Li Z, Matsouaka RA, Baron SJ, Vora AN, Mack MJ, Reynolds MR, Rumsfeld JS, Cohen DJ. Quality-of-Life Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in an Unselected Population: A Report From the STS/ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arnold SV, Reynolds MR, Lei Y, Magnuson EA, Kirtane AJ, Kodali SK, Zajarias A, Thourani VH, Green P, Rodés-Cabau J, Beohar N, Mack MJ, Leon MB, Cohen DJ; PARTNER Investigators. Predictors of poor outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: results from the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) trial. Circulation. 2014;129:2682-2690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van Ginkel DJ, Bor WL, Veenstra L, van 't Hof AWJ, Fabris E. Evolving concepts in the management of antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;101:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vlastra W, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Tchétché D, Chandrasekhar J, de Brito FS Jr, Barbanti M, Kornowski R, Latib A, D'Onofrio A, Ribichini F, Baan J, Tijssen JGP, De la Torre Hernandez JM, Dumonteil N, Sarmento-Leite R, Sartori S, Rosato S, Tarantini G, Lunardi M, Orvin K, Pagnesi M, Hernandez-Antolin R, Modine T, Dangas G, Mehran R, Piek JJ, Delewi R. Predictors, Incidence, and Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Complicated by Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Piccolo R, Pilgrim T, Franzone A, Valgimigli M, Haynes A, Asami M, Lanz J, Räber L, Praz F, Langhammer B, Roost E, Windecker S, Stortecky S. Frequency, Timing, and Impact of Access-Site and Non-Access-Site Bleeding on Mortality Among Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1436-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Auffret V, Leurent G, Le Breton H. Oral Anticoagulation Continuation Throughout TAVR: High Risk-High Reward or Marginal Gains? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:145-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Brown DL, Block PC, Guyton RA, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Douglas PS, Petersen JL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock S; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5086] [Cited by in RCA: 5506] [Article Influence: 367.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Möllmann H, Hengstenberg C, Hilker M, Kerber S, Schäfer U, Rudolph T, Linke A, Franz N, Kuntze T, Nef H, Kappert U, Walther T, Zembala MO, Toggweiler S, Kim WK. Real-world experience using the ACURATE neo prosthesis: 30-day outcomes of 1,000 patients enrolled in the SAVI TF registry. EuroIntervention. 2018;13:e1764-e1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nuis RJ, Van Mieghem NM, Schultz CJ, Moelker A, van der Boon RM, van Geuns RJ, van der Lugt A, Serruys PW, Rodés-Cabau J, van Domburg RT, Koudstaal PJ, de Jaegere PP. Frequency and causes of stroke during or after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1637-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Stortecky S, Windecker S, Pilgrim T, Heg D, Buellesfeld L, Khattab AA, Huber C, Gloekler S, Nietlispach F, Mattle H, Jüni P, Wenaweser P. Cerebrovascular accidents complicating transcatheter aortic valve implantation: frequency, timing and impact on outcomes. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Di Biase L, Burkhardt JD, Santangeli P, Mohanty P, Sanchez JE, Horton R, Gallinghouse GJ, Themistoclakis S, Rossillo A, Lakkireddy D, Reddy M, Hao S, Hongo R, Beheiry S, Zagrodzky J, Rong B, Mohanty S, Elayi CS, Forleo G, Pelargonio G, Narducci ML, Dello Russo A, Casella M, Fassini G, Tondo C, Schweikert RA, Natale A. Periprocedural stroke and bleeding complications in patients undergoing catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation with different anticoagulation management: results from the Role of Coumadin in Preventing Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Patients Undergoing Catheter Ablation (COMPARE) randomized trial. Circulation. 2014;129:2638-2644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Calkins H, Willems S, Gerstenfeld EP, Verma A, Schilling R, Hohnloser SH, Okumura K, Serota H, Nordaby M, Guiver K, Biss B, Brouwer MA, Grimaldi M; RE-CIRCUIT Investigators. Uninterrupted Dabigatran versus Warfarin for Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1627-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dewilde WJ, Janssen PW, Kelder JC, Verheugt FW, De Smet BJ, Adriaenssens T, Vrolix M, Brueren GB, Van Mieghem C, Cornelis K, Vos J, Breet NJ, ten Berg JM. Uninterrupted oral anticoagulation versus bridging in patients with long-term oral anticoagulation during percutaneous coronary intervention: subgroup analysis from the WOEST trial. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:381-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nijenhuis VJ, Stella PR, Baan J, Brueren BR, de Jaegere PP, den Heijer P, Hofma SH, Kievit P, Slagboom T, van den Heuvel AF, van der Kley F, van Garsse L, van Houwelingen KG, Van't Hof AW, Ten Berg JM. Antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing TAVI: an overview of Dutch hospitals. Neth Heart J. 2014;22:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |