Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.102104

Revised: December 14, 2024

Accepted: February 18, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 163 Days and 2.1 Hours

Cases of esophageal, airway, and pericardial perforations caused by chicken bone ingestion are rare worldwide, but their incidence has shown an upward trend in recent years. Injuries caused by chicken bones are often more severe, leading to infections and, in extreme cases, perforation of the common carotid artery, peri

We present a case of a patient who sustained combined esophageal and pericar

The patient’s symptoms and signs were not entirely consistent with myocardial infarction. Chest computed tomography played a crucial role in clarifying the etiology and provided critical evidence for devising an effective treatment stra

Core Tip: This case report presents a rare case of esophageal perforation and pericardial injury caused by chicken bone ingestion. The patient exhibited chest pain and pericardial effusion, with the diagnosis confirmed through computed tomography imaging. A multidisciplinary approach was adopted, involving surgical repair of the esophagus and pericardium. This case emphasizes the significance of rapid imaging diagnostics, multidisciplinary collaboration, and timely surgical management in addressing complex thoracic injuries.

- Citation: Ma N, Li ZW. Identification and management of esophageal and pericardial perforations: A case report. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(3): 102104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i3/102104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.102104

Esophageal perforation caused by fish bone ingestion is relatively common, whereas combined esophageal and peri

Intermittent epigastric pain with sweating and dizziness for 3 days.

The patient reported that 3 days prior he had accidentally ingested a chicken bone while eating, which had led to upper abdominal discomfort, sweating, dizziness, and headache. He reported having no experience of syncope, cough, sputum, nor diarrhea. A gastroscopy at a local county hospital had revealed a large food residue obstructing the esophagus at 23 cm from the incisor teeth. The endoscope had passed through, however, and the mucosa had appeared normal. The preliminary diagnosis was gastric retention and atrophic gastritis (C1 type), with an electrocardiogram indicating acute anterior myocardial infarction.

The patient was previously in good health with no history of illness. The patient's psycho-social history was unremar

The patient had no relevant family medical history. Detailed inquiry into the patient's medical history revealed that he had been in generally good health with a history of a previous left rib fracture. He did not have a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, or diabetes, and he had not experienced recurrent symptoms of chest tightness, shortness of breath, or chest pain. The current episode had begun acutely following the ingestion of a chicken bone, with symptoms worsening progressively.

The patient presented with temperature of 36.6 °C, pulse of 103 beats/min, respirations of 20 breaths/min, and blood pressure of 75/52 mmHg.

The chest was symmetrical, with diminished breath sounds in both lungs. No dry or wet rales were heard. No bulging was noted in the precordial area, and no thrills or pericardial friction rubs were palpated. Cardiac percussion revealed normal heart borders, with muffled heart sounds and a regular rhythm at 103 beats/min. There was no evidence of murmurs in the auscultation areas of the heart valves, and peripheral vascular signs were negative. The abdomen was soft with tenderness in the upper abdomen but no rebound tenderness. There was no edema in the lower extremities.

Upon admission, the patient underwent urgent laboratory tests, including complete blood count, blood biochemistry, coagulation function, bacterial infection markers, and blood gas analysis. The results are presented in Table 1.

| Parameter | Data finding | Normal range |

| C-reactive protein | 224.2 mg/L | < 10.00 mg/L |

| Serum amyloid A | > 320 mg/L | < 10.00 mg/L |

| White blood cell count | 14.7 × 109/L | 3.5-9.5 × 109/L |

| Neutrophils | 92.2% | 50%-75% |

| Lymphocytes | 3.3% | 20%-40% |

| Neutrophil count | 13.53 × 109/L | 1.2-7.0 × 109/L |

| Red blood cell count | 3.68 × 1012/L | 4-5.5 × 1012/L |

| Hemoglobin | 121 g/L | 120-160 g/L |

| Hematocrit | 35.7% | 40%-50% |

| Interleukin-6 | 510 pg/mL | < 7 pg/mL |

| Procalcitonin | 14.236 ng/mL | < 0.065 ng/mL |

| NT-proBNP | 670 pg/mL | < 125 pg/mL |

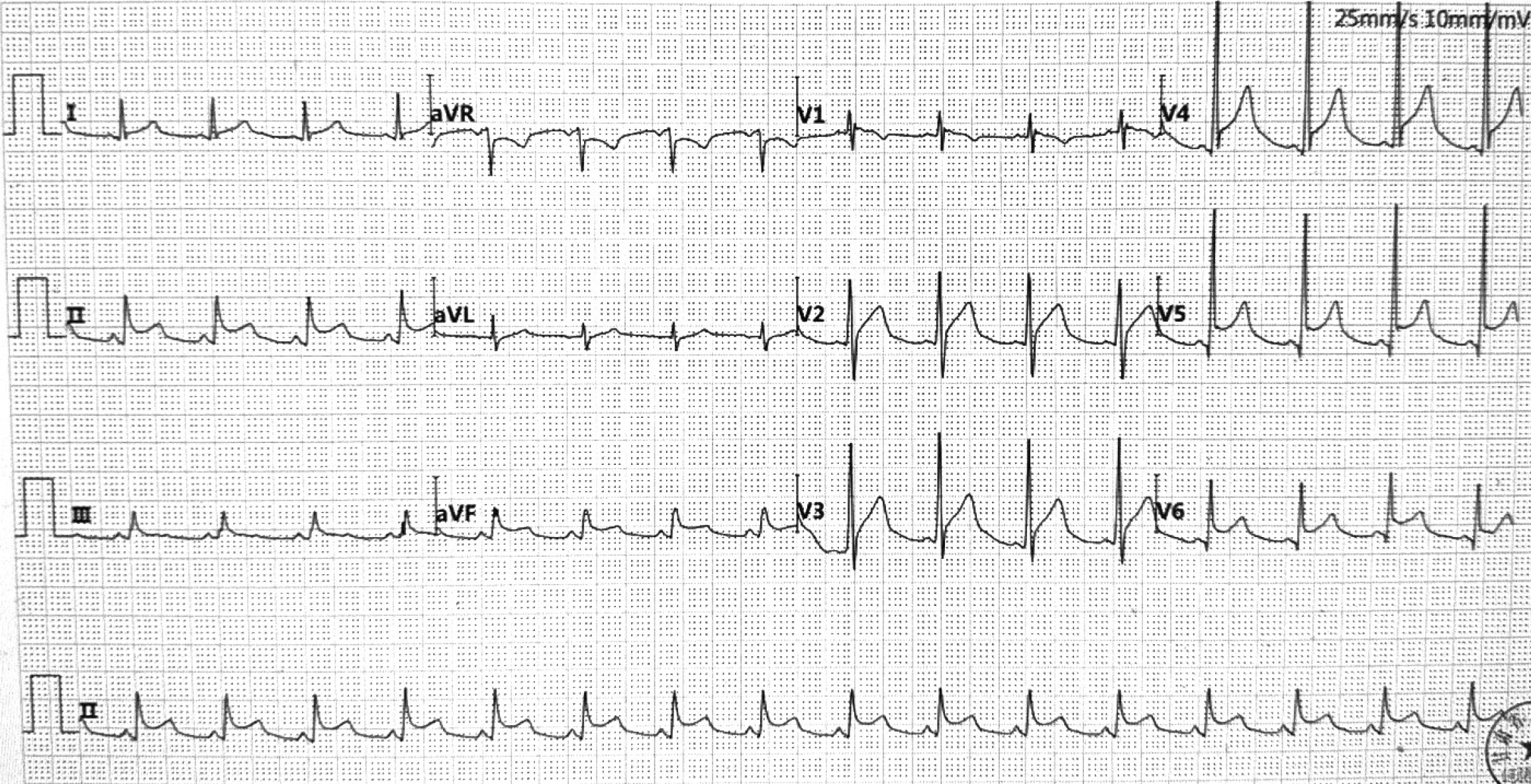

The findings were consistent with severe infection, most likely of bacterial origin. Furthermore, the patient had a reduced red blood cell count, raising concerns of potential bleeding. Although the electrocardiogram performed at the local county hospital had indicated extensive anterior and inferior myocardial infarctions (Figure 1), there was no significant elevation in cardiac enzymes detected. Considering that the patient’s upper abdominal pain had persisted for 3 days, there were no indications for emergency surgery and urgent coronary artery intervention was not performed. The lack of significant cardiac enzyme elevation indicated the possibility of myocardial infarction leading to a severe infection was unlikely, requiring further investigation into the infection risk.

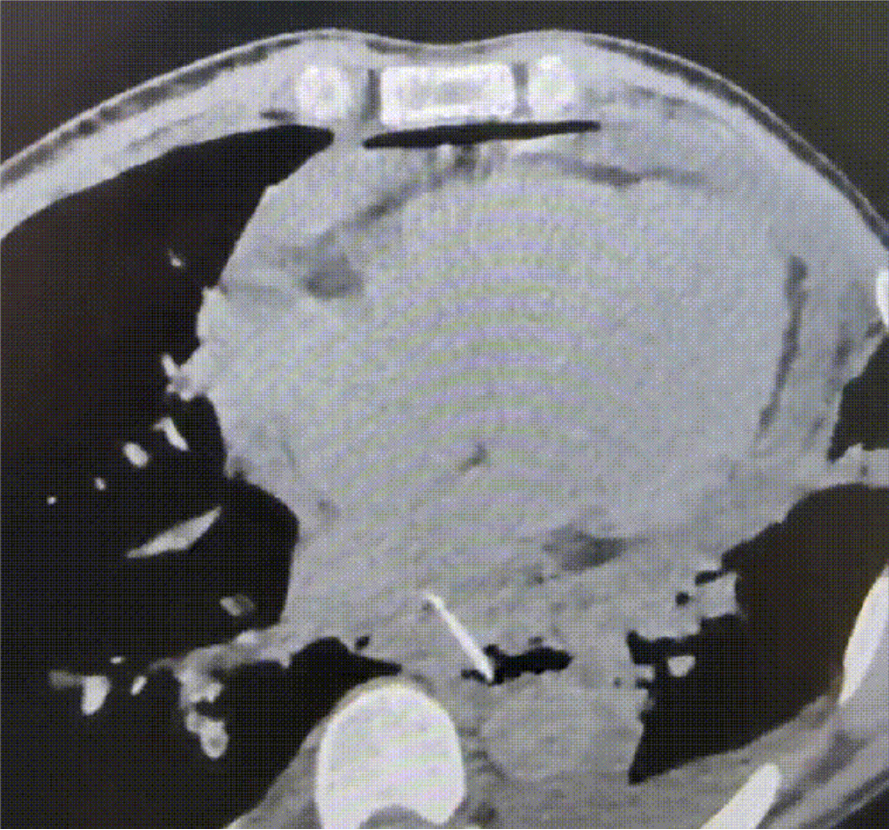

Considering the patient's history of chicken bone ingestion, acute complications related to esophageal perforation were suspected. To further evaluate the condition, cardiac echocardiography and chest/abdominal computed tomography (CT) were performed (Figure 2). CT imaging revealed a foreign body in the lower esophagus near the inferior border of the left atrium near the right anterior wall of the descending aorta. There was evidence of mediastinal and pericardial air, and a local irregularity was noted in the right posterior wall of the trachea at the carina level, raising suspicion of a perforation.

Cardiac echocardiography revealed segmental wall motion abnormalities, suggestive of myocardial ischemia, along with mild tricuspid and mitral valve regurgitation. Left ventricular systolic function was normal, and a small amount of pericardial effusion was present.

Chicken bone ingestion, causing injury to the esophageal and pericardial tissues.

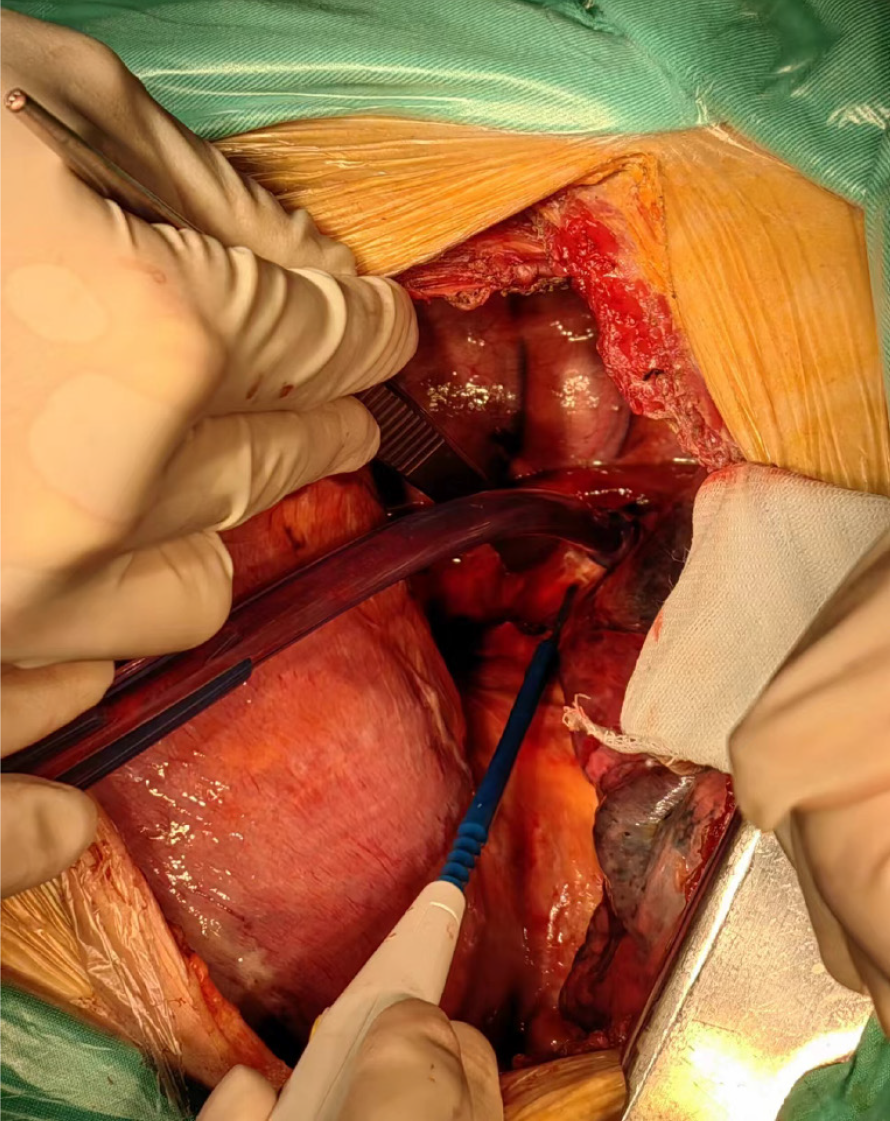

During surgery (Figure 3), a foreign body was found to have penetrated the esophagus and pierced the pericardium along the margin of the inferior pulmonary vein. Approximately 400 mL of pericardial effusion was observed, and the chicken bone was successfully removed (Figure 4).

Following surgery, the patient's condition improved and he was discharged in stable condition on postoperative Day 10 with recommendations for a liquid diet and follow-up imaging in 1 month to ensure complete healing of the esophagus and pericardium. However, the patient instead provided off-site reporting of significant symptom improvement and did not return for further follow-up.

The patient initially presented with intermittent upper abdominal pain, and electrocardiogram showed significant ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V3-V6, raising suspicion of acute myocardial infarction. However, the patient's blood tests suggested a severe infection, and negative cardiac enzyme results indicated that myocardial infarction was unlikely. Upon re-evaluating the patient's history, the possibility of a foreign body in the esophagus and perforating the pericardium was considered. Urgent chest CT and full aortic CT were performed, which confirmed the presence of a foreign body in the esophagus, trachea, and pericardium, thereby confirming the diagnosis.

In daily clinical practice, a thorough medical history should be obtained alongside a comprehensive physical examination, including inquiries about the timing of chicken bone ingestion, subsequent symptom changes, and whether the patient has a history of cardiac, pulmonary, thoracic soft tissue, skin, or gastrointestinal diseases. Differential diagnosis should be performed accordingly.

When suspecting this condition, a thorough evaluation with cervical and thoracic CT scans should be performed, as bones may often perforate the cervical esophagus, and CT imaging can help clarify the relationship between the foreign body and surrounding structures. Blind removal of foreign bodies under endoscopy should be avoided, as it may lead to multi-organ perforations with life-threatening consequences.

CT imaging has increasingly replaced endoscopy in diagnosing esophageal, tracheal, pericardial, and pulmonary injuries caused by swallowed foreign bodies, offering a more accurate and non-invasive method for identifying such injuries. CT scanning is considered to have 100% sensitivity, offering clear advantages over endoscopy[3]. First, CT is a non-invasive approach to assess the extent of the patient's injuries, clarify the relationship between the foreign body and adjacent structures, and evaluate the risk of involvement of major blood vessels or visceral organs[3]. Additionally, CT can identify complications such as soft tissue gas, fluid accumulation, and abscess formation caused by perforation. In contrast, endoscopy is limited to visualizing only the esophagus and stomach, and it cannot definitively determine whether the ingested foreign body has penetrated surrounding tissues. At times, the foreign body can even be mistaken for food residue, and blind forceps retrieval can worsen the patient’s condition. Therefore, CT imaging is increasingly preferred in the diagnosis of foreign body-induced esophageal, tracheal, pericardial, and pulmonary injuries, as it offers a more accurate and comprehensive assessment.

For patients with esophageal perforations, a retrospective analysis of 62 cases was performed to evaluate the associated causes, symptoms, treatment strategies, complications, and mortality rates. The study demonstrated that prompt surgical removal of the foreign body and repair of the damaged tissues is the preferred treatment approach for critically ill patients[4]. In a separate case report, Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (commonly known as REBOA) was successfully employed to control hemorrhage and minimize dissection around the aorta, thereby reducing surgical complexity and risks[2].

For complex cases of esophageal perforation involving thoracic organ injuries, rapid CT imaging and multidisciplinary collaboration play a pivotal role in achieving timely and accurate diagnosis. When aortic involvement is confirmed, utilizing REBOA as part of the management strategy offers a potential avenue for improving patient outcomes, parti

The patient’s symptoms and signs were not entirely consistent with myocardial infarction. Chest CT played a crucial role in clarifying the etiology and provided critical evidence for devising an effective treatment strategy.

| 1. | Aronberg RM, Punekar SR, Adam SI, Judson BL, Mehra S, Yarbrough WG. Esophageal perforation caused by edible foreign bodies: a systematic review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:371-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | El-Matbouly M, Suliman AM, Massad E, Albahrani A, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H. Triple Thoracic Injury Caused by Foreign Body Ingestion: A New Approach for Managing an Unusual Case. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e929119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koltka K, Sungur Z, İlhan M, Gök AFK, Bingül ES. Airway management of major blunt tracheal and esophageal injury: A case report. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022;28:120-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schmidt SC, Strauch S, Rösch T, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Jonas S, Pratschke J, Weidemann H, Neuhaus P, Schumacher G. Management of esophageal perforations. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2809-2813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |