Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.100506

Revised: October 24, 2024

Accepted: March 13, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 214 Days and 19 Hours

The EuroSCORE II is a globally accepted tool for predicting mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. However, the discriminative ability of this tool in non-European populations may be inadequate, limiting its use in other regions.

To evaluate the performance of EuroSCORE II in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery at a hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

An observational, analytical study of a retrospective cohort was designed. All patients admitted to Hospital Universitario Mayor Méderi who underwent CABG between December 2015 and May 2020 were included. In-hospital mortality was the primary outcome evaluated. Furthermore, the performance of EuroSCORE II was assessed in this population.

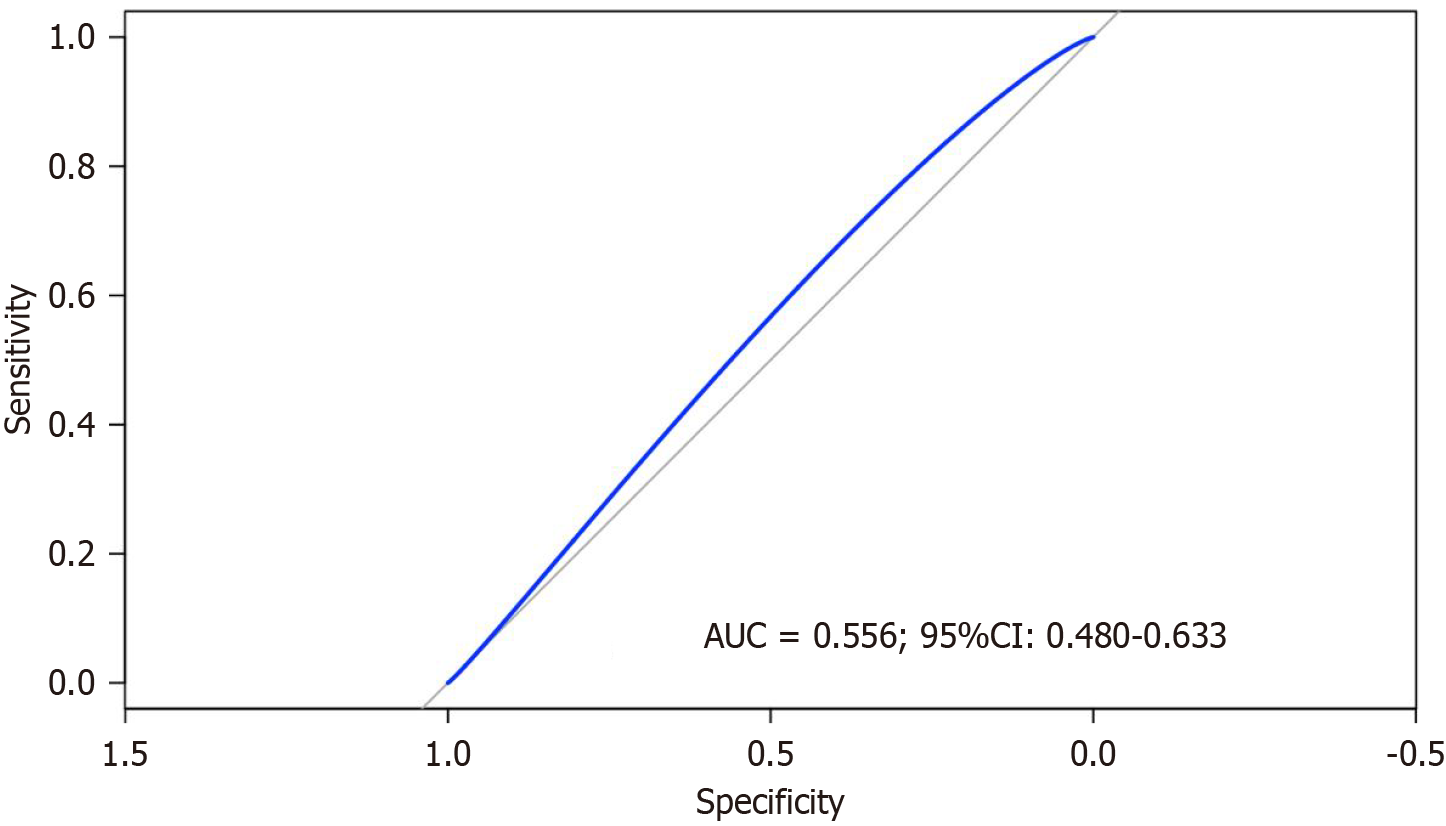

A total of 1009 patients were included [median age 66 years IQR = 59-72, 78.2% men]. The overall in-hospital mortality was 5.5% (n = 56). The median mortality predicted using EuroSCORE II was 1.29 (IQR = 0.92-2.11). Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was the most common preoperative diagnosis (54.1%), followed by ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (19.1%) and unstable angina (14.3%). Urgent surgery was performed in 87.3% of the patients (n = 881). Mortality rates in each group were as follows: Low risk 6.0% (n = 45, observed-to-expected (O/E) ratio, 5.6), moderate risk 3.0% (n = 5, O/E ratio 1.17), high risk 5.0% (n = 4, O/E ratio 0.94), and very high risk 7.6% (n = 2, O/E ratio 0.71). The overall O/E ratio was 4.2. The area under the curve of EuroSCORE II was 0.55 [95% confidence interval: 0.48-0.63]

EuroSCORE II exhibited poor performance in this population owing to its low discriminative ability. This finding may be explained by the fact that the population comprised older individuals with higher ventricular function impairment. Moreover, unlike the population in which this tool was originally developed, most patients were not electively admitted for the surgery.

Core Tip: Evaluating the EuroSCORE II in specific populations is crucial owing to the significant discrepancies reported between observed and expected mortality rates. Accurate assessment tools are essential for understanding and alleviating mortality rates in hospitals in developing countries. Tailoring EuroSCORE II to local contexts can facilitate informed public health decisions, optimize resource allocation, and ultimately enhance patient outcomes within healthcare systems.

- Citation: Rodríguez Lima DR, Rodríguez Aparicio EE, Otálora González L, Hernández DC, González-Muñoz A. Performance of the EuroSCORE in coronary artery bypass graft in Colombia, a middle-income country: A retrospective cohort. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(3): 100506

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i3/100506.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.100506

The EuroSCORE II is a globally accepted tool for predicting mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery[1,2]. Nonetheless, its predictive performance varies across different cohorts depending on age group, sex, and type of surgery[3-6]. Accurate mortality prediction and risk stratification of patients undergoing cardiac procedures remain challenging for physicians and healthcare systems, particularly when applying stratification scores to diverse populations. These variations can considerably affect decision-making and the definitive management of patients[7]. Risk models or scales must be calibrated based on specific characteristics of the population to which they are applied[7,8]. Adjusted mortality models, such as the risk-adjusted mortality ratio and the risk-adjusted mortality index (RAMI), augment the predictive ability of EuroSCORE II for individual centers or surgeons. These models achieve enhanced predictive capacity by dividing the actual (observed) mortality by the mortality estimated by the risk model[9]. A RAMI or observed-to-expected (O/E) mortality ratio of 1 signifies accurate estimation, a ratio of > 1 suggests an underestimation of mortality, and a ratio of < 1 indicates overestimation[10].

In Latin American countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, the tool has underestimated the mortality risk, with O/E mortality ratios reaching 2.46, despite maintaining acceptable discriminatory power, as indicated by an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.77 (0.76-0.81)[5]. Few studies have assessed the predictive capacity of EuroSCORE II in the Colombian population, showing an AUC of 0.75 and an O/E of 2.1[11]. Nevertheless, many patients presented characteristics beyond those included in the original score.

Estimating in-hospital death rates using available and/or billing data is essential for ranking hospitals according to their current rates of risk-adjusted predicted deaths. This evaluation is crucial for shaping health policies and informing public health decisions. In the cardiac surgery context, several scoring systems, including the Society of Thoracic Surgeons EuroSCORE I and EuroSCORE II, have demonstrated acceptable calibration and discrimination for predicting in-hospital mortality[12]. EuroSCORE II is commonly applied in our population.

This study aimed to describe the operative characteristics of EuroSCORE II in predicting in-hospital mortality for a large cohort of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures at a fourth-level hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

A retrospective cohort study with an observational and analytical design was conducted. The investigation included all patients aged ≥ 18 years who underwent CABG. Patients subjected to additional interventions besides revascularization during the same surgical procedure were excluded from the final analysis. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad del Rosario under reference number DVO005 2172-CV1656.

The study included all electronic medical records of patients admitted to Hospital Universitario Mayor Méderi who underwent CABG between December 2015 and May 2020. A convenience sampling method was adopted. Demographic variables were collected at hospital admission, including age, weight, height, and body mass index. In addition, preoperative status (comorbidities), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), EuroSCORE II, RAMI, diagnosis leading to surgical intervention, cardiac catheterization findings, and the urgency of the surgery (elective, urgent, or emergency) were recorded, along with the number of grafts and pump time. EuroSCORE II is a continuous variable that predicts in-hospital mortality risk and categorizes patients into four risk groups: Low (mortality 0%-2%), moderate (2.1%-4%), high (4.1%-8%), and very high (>8%). RAMI was calculated as the O/E mortality rates for the population and individual risk groups. The primary outcome evaluated was in-hospital mortality.

Mortality was classified as cardiac in origin if the treating physician attributed the death to pump failure or the progression of cardiogenic shock. Non-cardiac mortality was defined as that resulting from causes such as bleeding, vasoplegic shock, or cardiac tamponade. In addition, secondary clinical outcomes were documented, including reoperation for bleeding, stroke, surgical site infection/mediastinitis, length of hospital stay, and total days of hospitalization.

Demographic, clinical, surgical, and outcome variables were comprehensively described. The distribution of these variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were presented as rates, whereas continuous variables were reported as medians with their corresponding IQR or mean with standard deviations, depending on normality. Bivariate analyses were performed to explore the primary outcome of in-hospital mortality. Furthermore, the chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. In contrast, continuous variables were evaluated using either the t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test, depending on the normality of the data. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in determining between-group differences.

Mortality was assessed for each risk group classified according to EuroSCORE II (low, moderate, high, and very high). To evaluate the predictive performance of EuroSCORE II, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was employed, which plots the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1-specificity) at various threshold levels. The AUC was calculated to quantify the model’s ability to distinguish between survival and mortality for the entire population. Statistical analysis was performed using R software version 4.1.0 (Free Software Foundation’s GNU Public License).

The final analysis included 1009 patients who met the inclusion criteria, with a mean age of 66 years (IQR = 59-72). Men constituted 78.2% (n = 789) of the cohort. The overall mortality rate was 5.5% (n = 56), with a higher prevalence among men at 8.18% (n = 18). Cardiac-related mortality accounted for most deaths, comprising 34.7% (n = 35) compared with 2.0% (n = 21) deaths from non-cardiac causes. Hypertension was the most common clinical history, affecting 72.6% (n = 733) of the patients, followed by dyslipidemia in 36.5% (n = 369). The LVEF was slightly reduced among the survivors, with a mean of 45.5 (IQR = 34.7-55).

The median mortality rate predicted using EuroSCORE II was 1.29% (IQR = 0.92-2.11). Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction was the most frequent preoperative diagnosis, accounting for 54.1% (n = 546) of the cases, with a corresponding mortality rate of 6.2% (n = 34), followed by ST-elevation myocardial infarction, representing 19.1% (n = 193) of the cases, with a mortality rate of 6.7% (n = 13). Unstable angina comprised 14.3% (n = 145) of the cases, with a mortality rate of 4.1% (n = 6). Cardiac catheterization revealed that 62.8% (n = 634) of the patients had three compromised vessels, and the mortality rate was 5.6% (n = 36).

In this cohort, 87.3% (n = 881) of the patients underwent urgent surgery, with a mortality rate of 6.1% (n = 54), whereas 12.0% received elective surgery with no associated deaths. The CABG technique, involving the use of the internal mammary artery and the saphenous vein, was applied in 89% (n = 989) of the patients. Complete revascularization was achieved in 75.2% (n = 759) of the patients, whereas 24.7% (n = 250) experienced incomplete revascularization. The median perfusion time was 78 min (IQR = 60-93), and the median aortic clamp time was 58 min (IQR: 40-74).

Postoperative outcomes included coronary bridge dysfunction (16.8%, n = 17), sternal surgical site infection (7.1%, n = 72), and reintervention due to bleeding (4.1%, n = 42), all of which exhibited statistically significant differences between alive and dead patients. The mean length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) was 3 days (IQR = 2-5), and the overall in-hospital stay averaged 7 days (IQR = 5-9]. Readmission occurred in 5.3% (n = 54) of the patients. The key findings are summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | n = 1009 | Dead (n = 56) | Alive (n = 953) | P value |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (years) | 66 (59-72) | 71 (66.75-76) | 65 (59-72) | 1.02E-06 |

| Men | 789 (78.2) | 38 (4.82) | 751 (95.18) | 0.065912879 |

| Women | 220 (21.8) | 18 (8.18) | 202 (91.81) | 0.065912879 |

| Weight (kg) | 70 (64-77) | 66.5 (60-77.25) | 70 (64-77) | 0.087848882 |

| Height (kg) | 165 (160-170) | 163.5 (157.75-167) | 165 (160-170) | 0.014706242 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.64 (23.66-27.91) | 25.7 (23.3-29.08) | 25.6 (23.6-27.8) | 0.97572124 |

| Preoperative state | ||||

| Hypertension | 733 (72.6) | 51 (6.95) | 682 (93.04) | 0.000978778 |

| DM2 | 317 (31.4) | 20 (6.3) | 297 (93.69) | 0.462958515 |

| Hypothyroidism | 262 (25.9) | 17 (6.48) | 245 (93.51) | 0.435604718 |

| Smoking | 270 (26.76) | 11 (4.07) | 259 (95.92) | 0.27657479 |

| COPD | 86 (8.5) | 5 (5.81) | 81 (94.18) | 0.80753188 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 119 (11.79) | 15 (12.60) | 104 (87.4) | 0.001910342 |

| Dyslipidemia | 369 (36.57) | 14 (3.79) | 355 (96.20) | 0.08571374 |

| Peripheric arterial disease | 27 (2.6) | 4 (14.81) | 23 (85.18) | 0.057502526 |

| Stroke | 35 (3.47) | 2 (5.71) | 33 (94.28) | 1 |

| Obesity | 159 (15.76) | 9 (5.66) | 150 (94.33) | 1 |

| LVEF | 50 (41-57) | 45.5 (34.7-55) | 50 (42-57) | 0.017315231 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.29 (0.92-2.11) | 1.095 (0.88-1.84) | 1.31 (0.92-2.11) | 0.156214191 |

| RAMI | 4.26 (2.60-5.97) | 5.023 (2.99-6.25) | 4.19 (2.60-5.97) | 0.15 |

| Preoperatory diagnosis | ||||

| Unstable angina | 145 (14.37) | 6 (4.13) | 139 (95.86) | 0.511744128 |

| Stable angina | 78 (7.73) | 2 (2.56) | 76 (97.43) | |

| NSTEMI | 546 (54.11) | 34 (6.22) | 512 (93.77) | |

| STEMI | 193 (19.13) | 13 (6.73) | 180 (93.26) | |

| Other | 47 (4.66) | 1 (2.12) | 46 (97.87) | |

| Catheterization | ||||

| Compromised vessels | ||||

| 1 | 30 (2.97) | 0 | 30 (100) | 0.88005997 |

| 2 | 162 (16.06) | 10 (6.17) | 152 (93.82) | |

| 3 | 634 (62.83) | 36 (5.68) | 598 (94.32 | |

| 4 | 169 (16.75) | 10 (5.92) | 159 (94.08) | |

| 5 | 8 (0.079) | 0 | 8 (100) | |

| 6 | 6 (0.059) | 0 | 6 (100) | |

| Truncus | 232 (22.99) | 12 (5.17) | 220 (94.83) | 0.87104455 |

| Anterior descendent artery | 994 (98.51) | 56 (5.63) | 938 (94.37) | 1 |

| Circumflex artery | 809 (80.18) | 47 (5.80) | 762 (94.19) | 0.604726597 |

| Right coronary artery | 799 (79.19) | 47 (5.88) | 752 (94.12) | 0.497455644 |

| Ramus intermedius artery | 72 (7.14) | 4 (5.56) | 68 (94.44) | 1 |

| Surgery | ||||

| Elective surgery | 122 (12.09) | 0 | 122 (100) | 0.0010764 |

| Urgent surgery | 881 (87.31) | 54 (6.13) | 827 (93.87) | 0.036471079 |

| Emergency surgery | 46 (4.56) | 6 (13.04) | 40 (86.96) | 0.036994832 |

| Conventional (IMA + Saphenous vein) | 898 (89) | 52 (5.79) | 846 (94.21) | 0.23838081 |

| Arterial grafts | 54 (5.35) | 1 (1.85) | 53 (98.15) | |

| Venous grafts | 29 (2.87) | 3 (10.35) | 26 (89.65) | |

| Mix | 28 (2.78) | 0 | 28 (100) | |

| Complete revascularization | 759 (75.22) | 37 (4.87) | 722 (95.12) | 0.111696542 |

| Incomplete revascularization | 250 (24.78) | 19 (7.6) | 231 (92.4) | |

| Perfusion time EC (minutes) | 78 (60-93) | 81 (65.25-107.25) | 78 (60-93) | 0.127448435 |

| Aortic clamp time (minutes) | 58 (40-74) | 54 (36.25-73.5) | 58 (40-74) | 0.824799635 |

| Postoperative and hospitalization outcomes | ||||

| Reintervention for bleeding | 42 (4.16) | 12 (28.57) | 30 (71.43) | 8.05E-07 |

| POP stroke | 22 (2.18) | 5 (22.72) | 17 (77.28) | 0.005604736 |

| POP kidney failure | 39 (3.87) | 20 (51.28) | 19 (48.72) | 6.77E-17 |

| Surgical site infection sternum | 72 (7.14) | 10 (13.89) | 62 (86.11) | 4.49E-03 |

| Surgical site infection saphenectomy | 33 (3.27) | 2 (6.06) | 31 (93.94) | 0.704578221 |

| Mediastinitis | 35 (3.47) | 11 (31.43) | 24 (68.57) | 8.56E-07 |

| POP MI | 16 (1.59) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 0.000116377 |

| Vascular bridge dysfunction | 17 (16.8) | 7 (41.18) | 10 (58.82) | 1.40734E-05 |

| ICU stay (days) | 3 (2-5) | 6 (2-12) | 3 (2-4) | 0.000279016 |

| Hospitalization days | 7 (5-9) | 7.5 (2.75-14) | 7 (5-9) | 0.840229356 |

| Re-admission | 54 (5.35) | 4 (7.41) | 50 (92.59) | 0.534747149 |

| Mortality | 56 (5.55) | |||

| Cardiac death cause | 35 (34.7) | 0.00049975 | ||

| Non cardiac death cause | 21 (2.08) | |||

In-hospital mortality risk, as measured using EuroSCORE II and RAMI, is presented in Table 2. According to mortality risk classification, 739 patients were categorized as low risk, 164 as moderate risk, 80 as high risk, and 26 as very high risk. Mortality rates were 6.0% (n = 45, O/E ratio 5.6) for the low-risk group, 3.0% (n = 5, O/E ratio 1.17) for the moderate-risk group, 5% (n = 4, O/E ratio 0.94) for the high-risk group, and 7.6% (n = 2, O/E ratio of 0.72) for the very high-risk group. The mean EuroSCORE II values differed between deceased and surviving patients, with an overall O/E ratio of 4.2. Figure 1 depicts the ROC curve for EuroSCORE II, with an AUC of 0.556, indicating poor discrimination between survivors and non-survivors. The 95% confidence interval (95%CI; 0.48-0.63) further suggested that the model’s predictive accuracy was only marginally better than that of random chance.

| Risk | Dead | Alive | P value | EuroSCORE II | RAMI |

| Low | 45 (6.09) | 694 (93.91) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (0.82-1.42) | 5.63 |

| Moderate | 5 (3.05) | 159 (96.95) | 2.6 (2.3-3.2) | 1.17 | |

| High | 4 (5) | 76 (95) | 5.27 (4.56-5.75) | 0.94 | |

| Very high | 2 (7.69) | 24 (92.31) | 10.61 (9.39-13.72) | 0.72 |

Over the past century, perioperative cardiac surgery mortality risk has been estimated to determine self and institutional decision-making[13] and improve treatment strategies for high-risk surgeries such as aortic valve procedures[14]. Since its original publication, EuroSCORE II, one of the most commonly calculated mortality risk scores, has been adapted for local populations. Over the last decade, these adaptations have highlighted discrepancies based on patients’ age and surgical type and urgency[15,16].

Kuplay et al[17] conducted a study involving 116 octogenarian patients, assessing mortality risk prediction using EuroSCORE II. However, their findings indicated suboptimal score performance in combined and urgent surgeries. Similarly, van Dijk et al[18] performed one of the largest trials to determine the operative characteristics of EuroSCORE II within a population of 103404 patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgeries in the Netherlands. These researchers reported one of the most favorable O/E ratios (0.5-0.95) among the studied cohorts, suggesting a tendency for EuroSCORE II to overestimate mortality risk in cases involving urgent, combined, and even repeat surgeries. EuroSCORE II demonstrated good accuracy among European and North American populations, with an AUC of 0.7-0.85[18,19]. However, a recent retrospective study performed in 2022 in Milan, Italy, by Mastroiacovo et al[20] revealed that EuroSCORE II underestimated mortality risk across all types of surgery. In contrast, Asian and Latin American populations consistently exhibited lower accuracy[5,21-24].

This study represents one of the largest cohorts in Latin America examining the performance of EuroSCORE II. In another investigation, Roberto Parga-Gómez et al[25] studied a Colombian population and reported an O/E ratio of 1.31, with a predicted mortality rate of 5.34% and an observed mortality of 7.03%. A higher discrepancy was observed among patients undergoing high-risk surgery, yielding an O/E ratio of 1.5. In another Colombian study by Castro[26], the performance was deemed acceptable, with an AUC of 0.76 and an O/E ratio of 1.10.

EuroSCORE II demonstrated an AUC of 0.55 in this cohort, indicating poor discriminative ability. Furthermore, the O/E ratio was 4.2, highlighting a significant overestimation of risk. These results suggest that EuroSCORE II lacks sufficient predictive accuracy for clinical use in this population.

While mortality was underestimated in low- and moderate-risk groups, it was overestimated in high- and very high-risk groups. Mastroiacovo et al[20] reported an inverse association between risk scores and mortality estimates, revealing that mortality was underestimated in high-risk patients and overestimated in low-risk patients. In our case, mortality underestimation might have led to the wrong selection of candidates for cardiovascular surgery, potentially resulting in increased costs.

Borracci et al[27] examined the performance of EuroSCORE II in patients with low-risk stratification, showing an O/E ratio of 1.17. This higher observed mortality among these patients could be ascribed to systematic errors and other preventable factors, which are considered unusual[28]. The FIASCO study conducted in 2009, one of the largest studies in low-risk patients, concluded that mortality should be rare. The research identified that most errors stemmed from surgical technique and postoperative care[29]. However, careful interpretation of this conclusion is warranted as the O/E ratios in these instances were relatively close to 1.

The misclassification of patients as low risk based on EuroSCORE II should be considered, especially in populations with significant risk factors such as age, type of surgery, and the urgency of the surgery[15]. Ranucci et al[30] established that a simplified scoring system that included age, LVEF, serum creatinine level, emergency operations, and non-isolated coronary operations accurately predicted mortality risk, achieving an AUC of 0.75 and an O/E ratio close to 1. This finding implies that the EuroSCORE II model may overfit if it includes more than five risk factors[30]. While our study focused only on CABG surgery, typically considered a low risk factor, most deaths occurred in patients with reduced LVEF, and urgent coronary syndromes necessitated most procedures.

The findings from this study indicate that older age, compromised LVEF, and the necessity for urgent surgery are key determinants of increased mortality risk. Moreover, the results emphasize that EuroSCORE II lacks accuracy in this high-risk population. As a single-center retrospective cohort study, inherent selection bias might have existed in the patient population. In this era of aging populations and socioeconomic changes, especially in Latin America, patients and therapies should be accurately selected based on success probabilities prepended by mortality risk estimation. Factors such as older age, compromised LVEF, and the need for urgent surgery must be considered during risk stratification and decision-making by the clinical team. The costs of cardiac surgery vary among healthcare centers and depend on patient conditions. Utilizing the correct risk score for mortality prediction may provide estimates of expected costs by deducing patient death probabilities and anticipated ICU stay[31]. In addition, this approach helps determine the most cost-effective therapy for each patient[32].

EuroSCORE II demonstrated limited effectiveness in the Colombian population owing to its low discriminative ability [O/E ratio of 4.2 and AUC of 0.55 (95%CI: 0.48-0.63)]. This finding could be attributed to the demographic characteristics of the cohort, which was older, with a mean age of 66 years (IQR = 59-72), and exhibited more significant ventricular function impairment [LVEF 50% (IQR: 41-57)]. Furthermore, unlike the population in which this assessment tool was initially developed, most patients were not electively admitted for surgery.

| 1. | Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, Nilsson J, Smith C, Goldstone AR, Lockowandt U. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:734-44; discussion 744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1572] [Cited by in RCA: 2125] [Article Influence: 163.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Di Dedda U, Pelissero G, Agnelli B, De Vincentiis C, Castelvecchio S, Ranucci M. Accuracy, calibration and clinical performance of the new EuroSCORE II risk stratification system. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koszta G, Sira G, Szatmári K, Farkas E, Szerafin T, Fülesdi B. Performance of EuroSCORE II in Hungary: a single-centre validation study. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23:1041-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu PH, Shih HH, Kang PL, Pan JY, Wu TH, Wu CJ. Performance of the EuroSCORE II Model in Predicting Short-Term Mortality of General Cardiac Surgery: A Single-Center Study in Taiwan. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2022;38:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cerda-Núnez C, Yánez-Lillo J, Seguel E, Guinez-Molinos S. [Performance of EuroSCORE II in Latin America: a systematic review]. Rev Med Chil. 2022;150:424-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Silverborn M, Nielsen S, Karlsson M. The performance of EuroSCORE II in CABG patients in relation to sex, age, and surgical risk: a nationwide study in 14,118 patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;18:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koo SK, Dignan R, Lo EYW, Williams C, Xuan W. Evidence-Based Determination of Cut-Off Points for Increased Cardiac-Surgery Mortality Risk With EuroSCORE II and STS: The Best-Performing Risk Scoring Models in a Single-Centre Australian Population. Heart Lung Circ. 2022;31:590-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sinha S, Dimagli A, Dixon L, Gaudino M, Caputo M, Vohra HA, Angelini G, Benedetto U. Systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality risk prediction models in adult cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021;33:673-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | DesHarnais SI, Chesney JD, Wroblewski RT, Fleming ST, McMahon LF Jr. The Risk-Adjusted Mortality Index. A new measure of hospital performance. Med Care. 1988;26:1129-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Álvarez-cabo R, Meana B, Díaz R, Hernández-vaquero D, Pizcoya C, Mencía P, Llosa JC, Morales C, Silva J. Utilidad de EuroSCORE-II en pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica. Cirugía Cardiovascular. 2017;24:56-62. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jaramillo JM. Capacidad predictiva del EuroSCORE II en una cohorte de pacientes de cirugía cardiovascular en una institución de cuarto nivel de Bogotá. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Rosario. 2015. Available from: https://repository.urosario.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/915ea35c-67de-4149-811d-acef413128ea/content. |

| 12. | Argus L, Taylor M, Ouzounian M, Venkateswaran R, Grant SW. Risk Prediction Models for Long-Term Survival after Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024;72:29-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sullivan PG, Wallach JD, Ioannidis JP. Meta-Analysis Comparing Established Risk Prediction Models (EuroSCORE II, STS Score, and ACEF Score) for Perioperative Mortality During Cardiac Surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1574-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hahn RT, Pibarot P, Stewart WJ, Weissman NJ, Gopalakrishnan D, Keane MG, Anwaruddin S, Wang Z, Bilsker M, Lindman BR, Herrmann HC, Kodali SK, Makkar R, Thourani VH, Svensson LG, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Leon MB, Douglas PS. Comparison of transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement in severe aortic stenosis: a longitudinal study of echocardiography parameters in cohort A of the PARTNER trial (placement of aortic transcatheter valves). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2514-2521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Grant SW, Hickey GL, Dimarakis I, Cooper G, Jenkins DP, Uppal R, Buchan I, Bridgewater B. Performance of the EuroSCORE models in emergency cardiac surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:178-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Politi MT, Di Benedetto S, Ferreyra R, Bortman G, Piazza A, Capurro C. [Characterization and risk prediction of cardiovascular surgeries with cardiopulmonary bypass: a cross-sectional study]. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba. 2024;81:233-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kuplay H, Bayer Erdoğan S, Baştopçu M, Karpuzoğlu E, Er H. Performance of the EuroSCORE II and the STS score for cardiac surgery in octogenarians. Turk Gogus Kalp Damar Cerrahisi Derg. 2021;29:174-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Dijk WB, Leeuwenberg AM, Grobbee DE, Siregar S, Houterman S, Daeter EJ, de Vries MC, Groenwold RHH, Schuit E; Cardiothoracic Surgery Registration Committee of the Netherlands Heart Registration. Dynamics in cardiac surgery: trends in population characteristics and the performance of the EuroSCORE II over time. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;64:; ezad301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stavridis G, Panaretos D, Kadda O, Panagiotakos DB. Validation of the EuroSCORE II in a Greek Cardiac Surgical Population: A Prospective Study. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2017;11:94-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mastroiacovo G, Bonomi A, Ludergnani M, Franchi M, Maragna R, Pirola S, Baggiano A, Caglio A, Pontone G, Polvani G, Merlino L. Is EuroSCORE II still a reliable predictor for cardiac surgery mortality in 2022? A retrospective study study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;64:ezad294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bai Y, Wang L, Guo Z, Chen Q, Jiang N, Dai J, Liu J. Performance of EuroSCORE II and SinoSCORE in Chinese patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;23:733-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kalender M, Adademir T, Tasar M, Ecevit AN, Karaca OG, Salihi S, Buyukbayrak F, Ozkokeli M. Validation of EuroSCORE II risk model for coronary artery bypass surgery in high-risk patients. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2014;11:252-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shan L, Ge W, Pu Y, Cheng H, Cang Z, Zhang X, Li Q, Xu A, Wang Q, Gu C, Zhang Y. Assessment of three risk evaluation systems for patients aged ≥70 in East China: performance of SinoSCORE, EuroSCORE II and the STS risk evaluation system. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zahara R, Soeharto DF, Widyantoro B, Sugisman, Herlambang B. Validation of EuroSCORE II Scoring System on Isolated CABG Patient in Indonesia. Egypt Heart J. 2023;75:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Parga-Gómez R, Buitrago-Gutiérrez G, Roldán-Henao J. Validación del euroSCORE en la valoración del riesgo quirúrgico en un centro de referencia cardiovascular en Colombia. Rev Mex Cardiol. 2013;24:138-143. |

| 26. | Castro E. Valor predictivo del modelo euroscore ii en cirugía cardiaca en el Hospital Universitario Mayor Mederi de la ciudad de Bogotá. [24 October 2024]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10654/12433. |

| 27. | Borracci RA, Rubio M, Baldi J Jr, Ahuad Guerrero RA, Mauro V. Mortality in low- and very low-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery: evaluation according to the EuroSCORE II as a new standard. Cardiol J. 2015;22:495-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lidén K, Ivert T, Sartipy U. Death in low-risk cardiac surgery revisited. Open Heart. 2020;7:e001244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Freed DH, Drain AJ, Kitcat J, Jones MT, Nashef SA. Death in low-risk cardiac surgery: the failure to achieve a satisfactory cardiac outcome (FIASCO) study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9:623-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ranucci M, Castelvecchio S, Menicanti L, Frigiola A, Pelissero G. Accuracy, calibration and clinical performance of the EuroSCORE: can we reduce the number of variables? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:724-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nilsson J, Algotsson L, Höglund P, Lührs C, Brandt J. EuroSCORE predicts intensive care unit stay and costs of open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1528-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | D'Errigo P, Marcellusi A, Biancari F, Barbanti M, Cerza F, Tarantini G, Ranucci M, Ussia GP, Costa G, Badoni G, Fraccaro C, Meucci F, Baglio G, Seccareccia F, Tamburino C, Rosato S; OBSERVANT II Research Group. Financial Burden of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2023;203:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |