Published online Jun 26, 2024. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v16.i6.314

Revised: June 3, 2024

Accepted: June 13, 2024

Published online: June 26, 2024

Processing time: 57 Days and 12.1 Hours

Perforation of the right ventricle during placement of pacing wires is a well-documented complication and can be potentially fatal. Use of temporary pace

Core Tip: Early recognition and timely diagnosis using advanced multimodality imaging can guide surgical intervention and prevent unfavourable consequences of device-related complications.

- Citation: Acharya M, Kavanagh E, Garg S, Sef D, De Robertis F. Management of a patient with an unusual trajectory of a temporary trans-venous pacing lead. World J Cardiol 2024; 16(6): 314-317

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v16/i6/314.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v16.i6.314

Perforation of the right ventricle during placement of pacing wires is a well-documented complication and can be potentially fatal[1]. Up to 9% of patients can experience a variety of complications after permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation such as infections, battery or programming issues, lead migration, or lead fracture[2]. Pericardial effusion, consistent with cardiac perforation, can be detected in up to 1.2% of patients after the PPM implantation. Use of temporary pacemaker, helical screw leads and steroids use prior to implant are recognised as risk factors for development of post-PPM effusion[1].

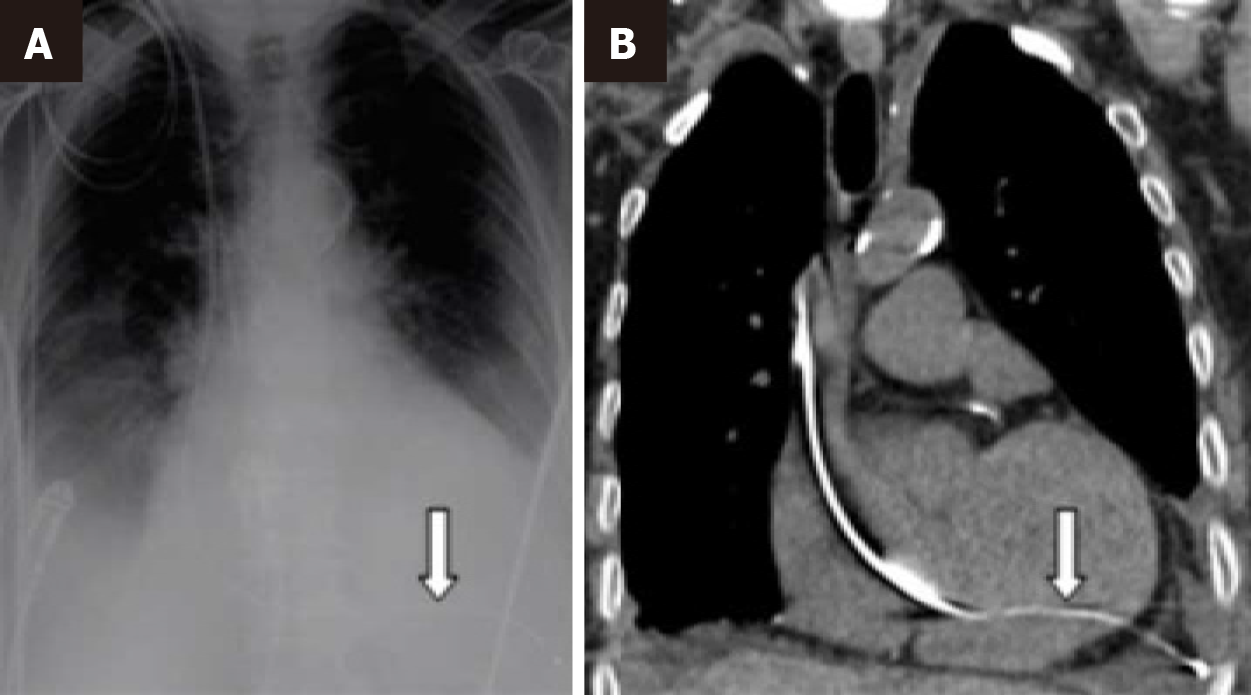

We reported an unusual case of pacing wire perforating interventricular septum into the left ventricle. An 81-year-old woman presenting at a district hospital in decompensated heart failure with fast atrial fibrillation and pleural effusions underwent emergency temporary trans-jugular venous pacing using passive leads for complete heart block after beta-blockade for rate control. On the next day, a loss of PPM capture was detected on monitoring and prompted further work-up. Chest radiography (Figure 1A, arrow) and computed tomography (Figure 1B, arrow) showed that the pacing wire had traversed from the inter-ventricular septum into the left ventricle, and through the left ventricular myocardium to lie within the left pleura.

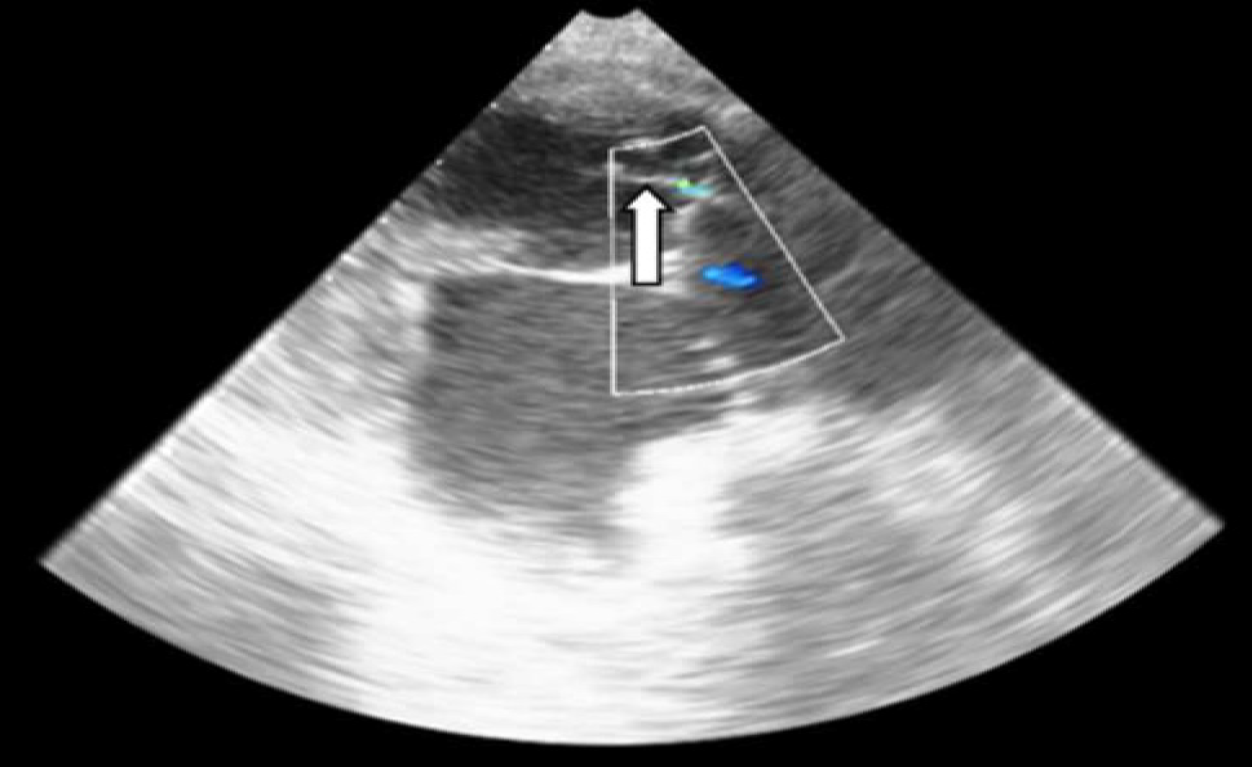

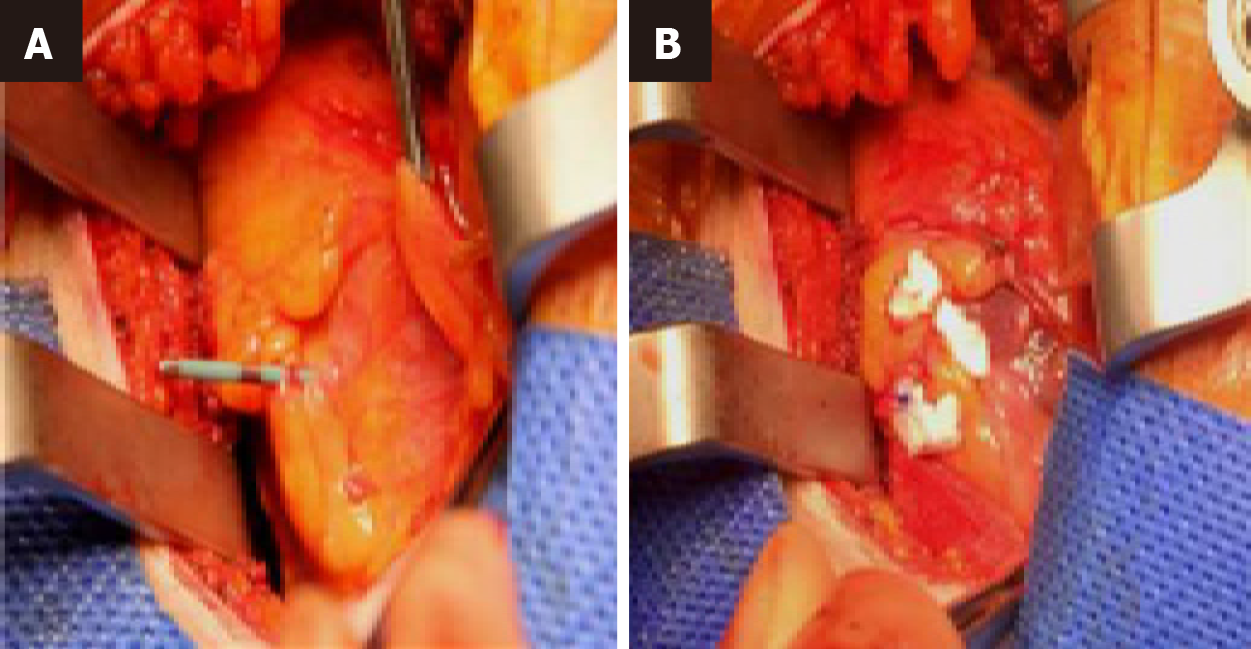

The patient was transferred to our tertiary cardiothoracic centre. Transoesophageal echocardiogram on admission demonstrated severe Carpentier IIIB mitral regurgitation from chordal entrapment by the pacing wire (Figure 2, arrow), without pericardial effusion. Multi-disciplinary team consensus was obtained for surgical pacing wire removal. Following left anterior thoracotomy in the 6th intercostal space, a Teflon-pledgeted 3-0 polypropylene purse-string suture was tied around the protruding pacing wire at the left ventricular apex (Figure 3) alongside transvenous lead withdrawal. The patient made a satisfactory recovery with only mild mitral regurgitation detected postoperatively.

Placement of temporary pacing leads has been associated with a 3-fold increased risk of cardiac perforation[1]. Therefore, in a Mayo Clinic study, which included more than 4200 patients who had PPM implantation, authors postulated that temporary pacemaker placement should be avoided unless essential[1]. In the case of symptomatic malpositioned pacing lead within the left ventricle, emergent surgical extraction is generally required[3]. Similarly, Mortensen et al[4] reported on a case of ventricular lead perforation late after PPM implantation with isolated haemothorax and no cardiac effusion or tamponade[4]. Definitive diagnosis was established only after fluoroscopy, and the surgical treatment included lead removal, repair suture of the right ventricle and placement of an epicardial electrode via thoracotomy. On the other hand, Otaal et al[5] reported a case of ventricular perforation in a patient who presented with mild left-sided chest pain 3 days after PPM implantation[5]. Diagnosis was confirmed with a computed tomography which detected hemopneumothorax[6]. The patient underwent successful surgical management with the placement of an epicardial pacemaker lead. For some of the above-mentioned reasons, leadless PPM is recently becoming an alternative form of transvenous pacing since it has been demonstrated that lead- and pocket-related complications can be reduced using this relatively novel approach[7]. However, the pacing position of leadless PPM can be more challenging as compared to conventional PPM, requiring careful preimplantation evaluation.

In our opinion, early recognition and timely diagnosis using advanced multimodality imaging can guide surgical intervention and prevent unfavourable consequences of device-related complications.

| 1. | Mahapatra S, Bybee KA, Bunch TJ, Espinosa RE, Sinak LJ, McGoon MD, Hayes DL. Incidence and predictors of cardiac perforation after permanent pacemaker placement. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:907-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kumar P, Skrabal J, Frasure SE, Pourmand A. Pacemaker lead related myocardial perforation. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;53:281.e1-281.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Iwata S, Hirose A, Furui I, Matsumoto T, Ozaki M, Nagasaka Y. Right ventricular perforation, pneumothorax, and a pneumatocele by a pacemaker lead: a case report. JA Clin Rep. 2021;7:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mortensen K, Aydin MA, Goldmann B, Deuse T, Willems S, Ventura R. Fluoroscopy to assess late heart and lung perforation by a permanent ventricular pacemaker lead. A case complicated by isolated hemothorax. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:104-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Otaal PS, Budakoty S, Kumar R, Singhal MK. Hemopneumothorax due to subacute right ventricular perforation by a pacemaker lead with subtle clinical presentation. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11:780-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sef D, Birdi I. Clinically significant incidental findings during preoperative computed tomography of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2020;31:629-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee JZ, Mulpuru SK, Shen WK. Leadless pacemaker: Performance and complications. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:130-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |