Published online May 26, 2024. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v16.i5.217

Revised: April 18, 2024

Accepted: May 13, 2024

Published online: May 26, 2024

Processing time: 175 Days and 1.9 Hours

In this editorial, we comment on the article by Kong et al published in the recent issue of the World Journal of Cardiology. In this interesting case, the authors present the challenges faced in managing a 13-year-old patient with Down syndrome (DS) and congenital heart disease (CHD) associated with pulmonary arterial hyper

Core Tip: Addressing the health challenges of individuals with Down syndrome (DS) poses intricate challenges, with congenital heart disease (CHD) being notably prevalent. The complexity of managing DS and CHD is heightened by diagnostic delays and difficulties in symptom assessment due to intellectual disabilities. Incorporating this unique population into comprehensive studies and randomized trials, with careful consideration of informed consent and a multidisciplinary research framework, is crucial.

- Citation: Drakopoulou M, Vlachakis PK, Tsioufis C, Tousoulis D. Congenital heart “Challenges” in Down syndrome. World J Cardiol 2024; 16(5): 217-220

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v16/i5/217.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v16.i5.217

In this editorial we comment on the article by Kong et al[1] published in the recent issue of the World Journal of Cardiology[1]. In this interesting case, the Authors present the challenges faced in managing a 13-year-old patient with Down syndrome (DS) and congenital heart disease (CHD) associated with pulmonary hypertension (PH). In this article, the Authors underscore the high incidence of CHD in patients with DS and the need for early diagnosis and management. Indeed, about half of infants born with DS are identified with CHD, a stark contrast to the general population’s approximate 1% incidence[2]. Moreover, Authors, highlight the need of a multidisciplinary approach for decision making in this distinct population with DS and concomitant CHD associated with PH. Based on recently published European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, shunt closure (intracardiac and/or extracardiac) in the presence of pulmonary arterial hypertension seem not to be appropriate in patients with increased pulmonary vascular resistance (> 5 WU) and may only be considered after careful evaluation in specialized centers and individualization. Most importantly, in the aforementioned guidelines as well as current ESC guidelines in adult CHD there is no referral to patients with DS and data concerning this population management is limited[3].

It was in 1866 when Down[4] first described the features of DS, and in 1959 when Lejeune et al[5] linked the syndrome to the chromosomal abnormality of trisomy 21[1,4]. Since then, DS has constituted one of the most common chromosomal abnormalities, affecting nearly 11.8 per 10000 live births[6]. In tandem with the joy of these unique individuals comes the intricate challenge of managing associated health complications, with CHDs standing out prominently.

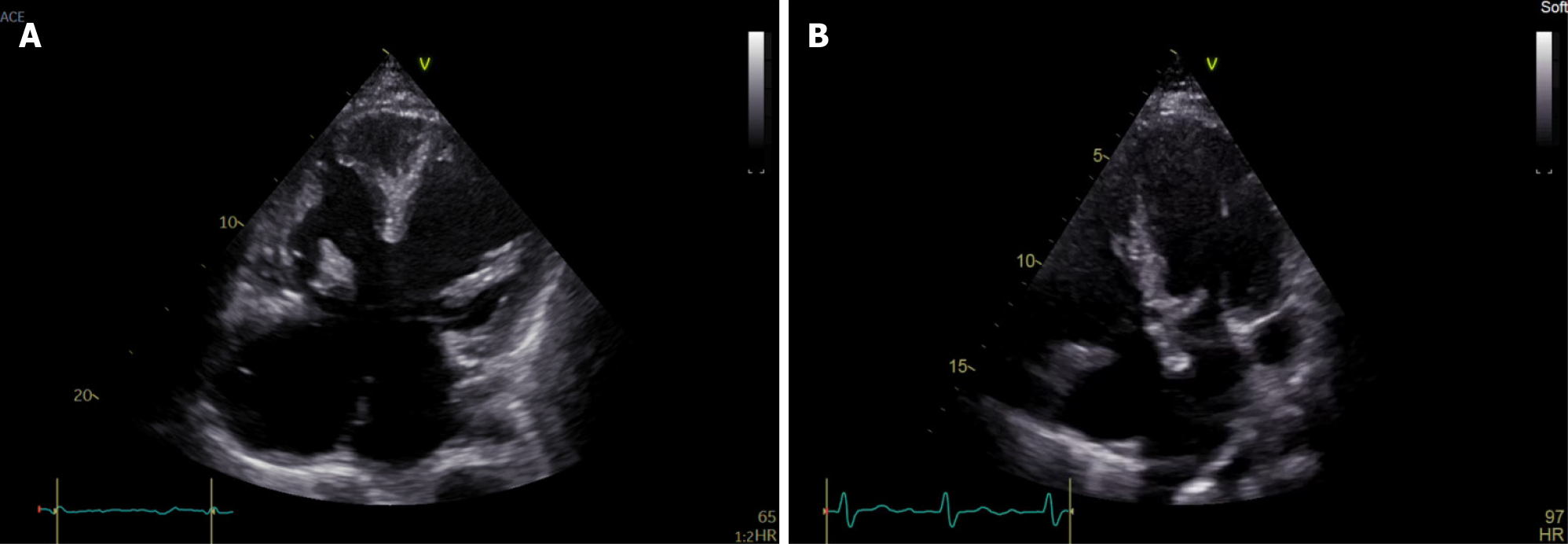

Recognition of the diverse clinical presentations of CHDs in DS is imperative for timely diagnosis and intervention. So far, atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) remains the most common CHD in this susceptible population (Figure 1)[7]. In a population-based study from 1985 to 2006 in northeastern England, 42% of infants with DS exhibited cardiovascular abnormalities. Among 821 infants, 23% had multiple anomalies, with atrial septal defect (ASD) or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) being common secondary lesions. Primary lesions included complete-AVSD (37%), ventricular septal defect (31%), ASD (15%), partial-AVSD (6%), Tetralogy of Fallot (5%), and PDA (4%). Miscellaneous anomalies constituted 2%[8]. Data revealed a shift in the distribution of CHD in DS over time, noting a tendency toward simpler lesions in recent years. One hypothesis is that this trend might be influenced by improved survival rates in simple lesions. Alternatively, it could indicate a higher incidence of prenatal diagnosis and an increased likelihood of terminating pregnancies involving more complex defects[9].

Diagnostic modalities tailored to the distinctive features of DS patients are pivotal. A consensus document recently published by Dimopoulos et al[9] on behalf of the DS international network supports systematic screening for the detection of CHDs in newborns diagnosed with or suspected of having DS[10]. This comprehensive screening involves clinical examination, electrocardiogram, and, where available, echocardiography. In health systems equipped with obstetric ultrasound screening, it is advisable to screen fetuses with suspected or confirmed DS during the second trimester[10]. Fetal echocardiography should be considered, particularly for women with conditions linked to high rates of CHD or when fetal ultrasound suggests a potential abnormality[11]. In cases of prenatal diagnosis of both CHD and DS, it is crucial to establish a delivery plan with expert support to effectively manage the complications arising from CHD and associated lesions.

The landscape of CHD treatment underwent a transformative shift in the 1960s and early 1970s with the widespread of open-heart surgery[12]. Initially excluded, DS patients gradually became candidates. Improved outcomes and successful cardiac repairs shifted societal attitudes, making surgery standard for DS patients with CHD. Referral to a specialized center for management is advised for all individuals with DS and CHD, with the timing and nature of repair contingent on CHD type, clinical presentation, and the specific risk of developing PH. For infants amenable to biventricular repair, early CHD repair is recommended, irrespective of DS presence, as DS doesn’t pose a higher perioperative risk for most CHD types[9]. Despite increased perioperative risk, individuals with DS and single ventricle physiology should be considered for Fontan palliation when suitable[13].

Regular assessment for PH is essential for all individuals with DS and CHD, both before CHD repair and at intervals thereafter. The management of individuals with DS and PH is often complicated, leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation or escalation. Defining symptomatology can be challenging due to intellectual disabilities, rendering traditional assessments like the 6-minute walk test less reliable[14]. Additionally, the higher prevalence of comorbidities in these individuals, such as obstructive sleep apnea, lung disease, and others, further complicates the clinical presentation and response to therapies. Limited data on the efficacy of PH therapy in DS individuals highlight the importance of their identification and referral to specialist centers for comprehensive care[15,16]. Diagnosing PH, identifying its causes, and determining optimal management require specialized expertise.

In conclusion, fostering multidisciplinary collaboration and advancing ongoing research initiatives are pivotal for a patient-centric approach to CHDs in individuals with DS. Unraveling the complexities of this intersection provides clinicians with the insights needed for optimal care. The imperative for research persists, focusing on early diagnosis, person-centered follow-up, health-related quality of life assessment, and the timing of interventions. Encouraging the inclusion of individuals with DS in randomized trials and comprehensive studies, supported by informed consent and a multidisciplinary research framework, is pivotal for addressing the unique challenges associated with intellectual disability in this population.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Nemes Attila A, Hungary S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Kong MW, Li YJ, Li J, Pei ZY, Xie YY, He GX. Down syndrome child with multiple heart diseases: A case report. World J Cardiol. 2023;15:615-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Stoll C, Dott B, Alembik Y, Roth MP. Associated congenital anomalies among cases with Down syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58:674-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, Budts W, Chessa M, Diller GP, Lung B, Kluin J, Lang IM, Meijboom F, Moons P, Mulder BJM, Oechslin E, Roos-Hesselink JW, Schwerzmann M, Sondergaard L, Zeppenfeld K; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:563-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 1170] [Article Influence: 292.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Down JL. Observations on an ethnic classification of idiots. 1866. Ment Retard. 1995;33:54-56. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lejeune J, Turpin R, Gautier M. Mongolism; a chromosomal disease (trisomy). Bull Acad Natl Med. 1959;143:256-265. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Shin M, Besser LM, Kucik JE, Lu C, Siffel C, Correa A; Congenital Anomaly Multistate Prevalence and Survival Collaborative. Prevalence of Down syndrome among children and adolescents in 10 regions of the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1565-1571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kidd SA, Lancaster PA, McCredie RM. The incidence of congenital heart defects in the first year of life. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993;29:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Irving CA, Chaudhari MP. Cardiovascular abnormalities in Down's syndrome: spectrum, management and survival over 22 years. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:326-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dimopoulos K, Constantine A, Clift P, Condliffe R, Moledina S, Jansen K, Inuzuka R, Veldtman GR, Cua CL, Tay ELW, Opotowsky AR, Giannakoulas G, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Cordina R, Capone G, Namuyonga J, Scott CH, D'Alto M, Gamero FJ, Chicoine B, Gu H, Limsuwan A, Majekodunmi T, Budts W, Coghlan G, Broberg CS; for Down Syndrome International (DSi). Cardiovascular Complications of Down Syndrome: Scoping Review and Expert Consensus. Circulation. 2023;147:425-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Velzen CL, Clur SA, Rijlaarsdam ME, Pajkrt E, Bax CJ, Hruda J, de Groot CJ, Blom NA, Haak MC. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects: accuracy and discrepancies in a multicenter cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:616-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cooper A, Sisco K, Backes CH, Dutro M, Seabrook R, Santoro SL, Cua CL. Usefulness of Postnatal Echocardiography in Patients with Down Syndrome with Normal Fetal Echocardiograms. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;40:1716-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sondheimer HM, Byrum CJ, Blackman MS. Unequal cardiac care for children with Down's syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:68-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Campbell RM, Adatia I, Gow RM, Webb GD, Williams WG, Freedom RM. Total cavopulmonary anastomosis (Fontan) in children with Down's syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:523-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vis JC, Thoonsen H, Duffels MG, de Bruin-Bon RA, Huisman SA, van Dijk AP, Hoendermis ES, Berger RM, Bouma BJ, Mulder BJ. Six-minute walk test in patients with Down syndrome: validity and reproducibility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1423-1427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Galiè N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis MA, Granton J, Berger RM, Lauer A, Chiossi E, Landzberg M; Bosentan Randomized Trial of Endothelin Antagonist Therapy-5 (BREATHE-5) Investigators. Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation. 2006;114:48-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 590] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Diller GP, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Dimopoulos K, Alvarez-Barredo M, Koo C, Kempny A, Harries C, Parfitt L, Uebing AS, Swan L, Marino PS, Wort SJ, Gatzoulis MA. Disease targeting therapies in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: response to treatment and long-term efficiency. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:840-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |