Published online Mar 26, 2024. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v16.i3.104

Peer-review started: November 21, 2023

First decision: December 29, 2023

Revised: January 12, 2024

Accepted: February 18, 2024

Article in press: February 18, 2024

Published online: March 26, 2024

Processing time: 120 Days and 16 Hours

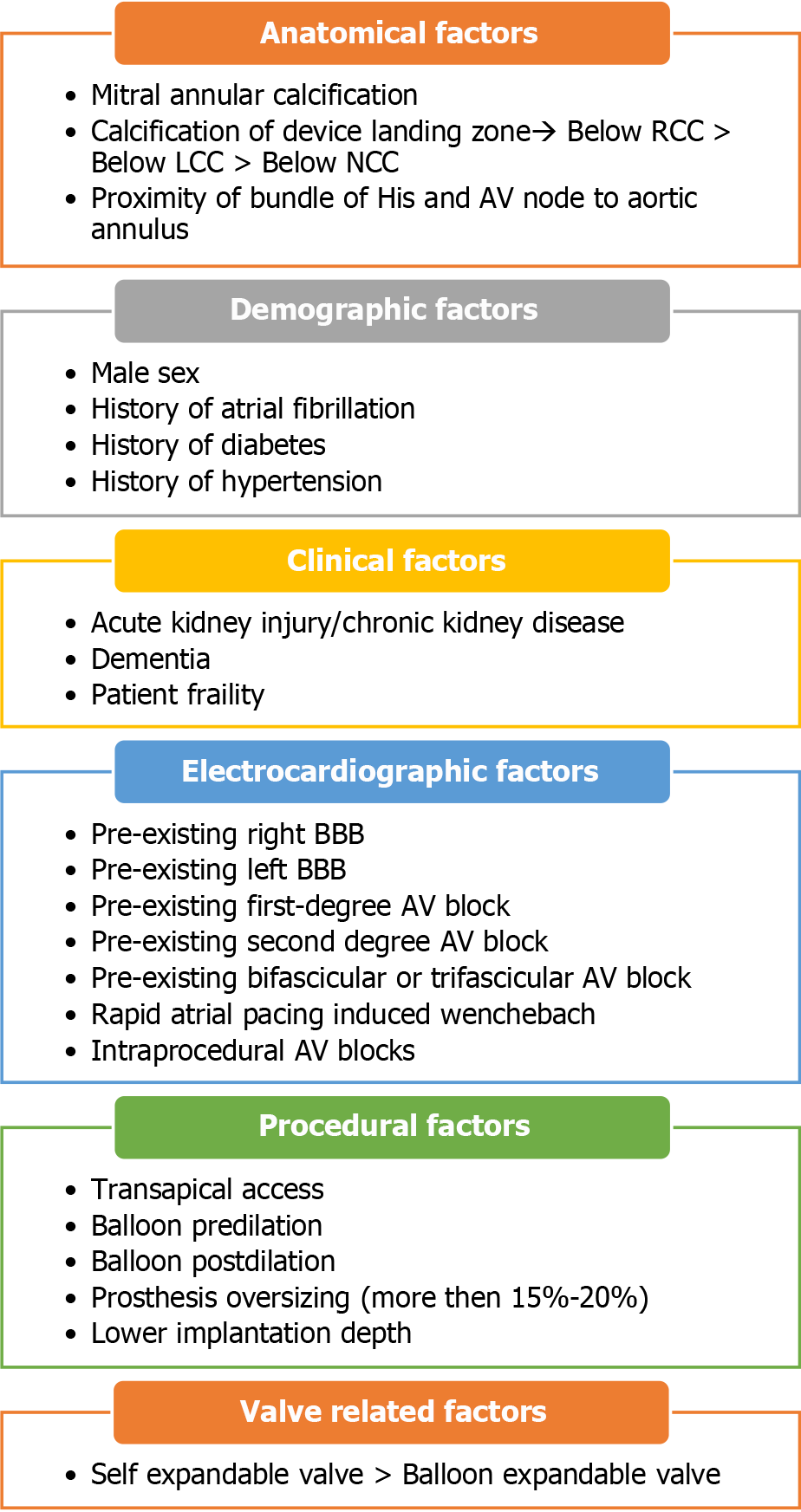

Several anatomical, demographic, clinical, electrocardiographic, procedural, and valve-related variables can be used to predict the probability of developing con

Core Tip: Several anatomical, demographic, clinical, electrocardiographic, procedural, and valve-related variables predict the probability of developing conduction abnormalities after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) that necessitate permanent pacemaker placement. The current study reinforces the existing literature by demonstrating that type 2 diabetes mellitus and baseline right bundle branch block are significant predictors of pacemaker implantation post-TAVR. The study investigators also revealed a novel linear relationship between the post-TAVR incidence of pacemaker implantation with every 20 ms increase in baseline QRS duration. Interestingly, pacemaker implantation following TAVR was predictive of future cardiovascular events at 1 year.

- Citation: Prajapathi S, Pradhan A. Predictors of permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement-the search is still on! World J Cardiol 2024; 16(3): 104-108

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v16/i3/104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v16.i3.104

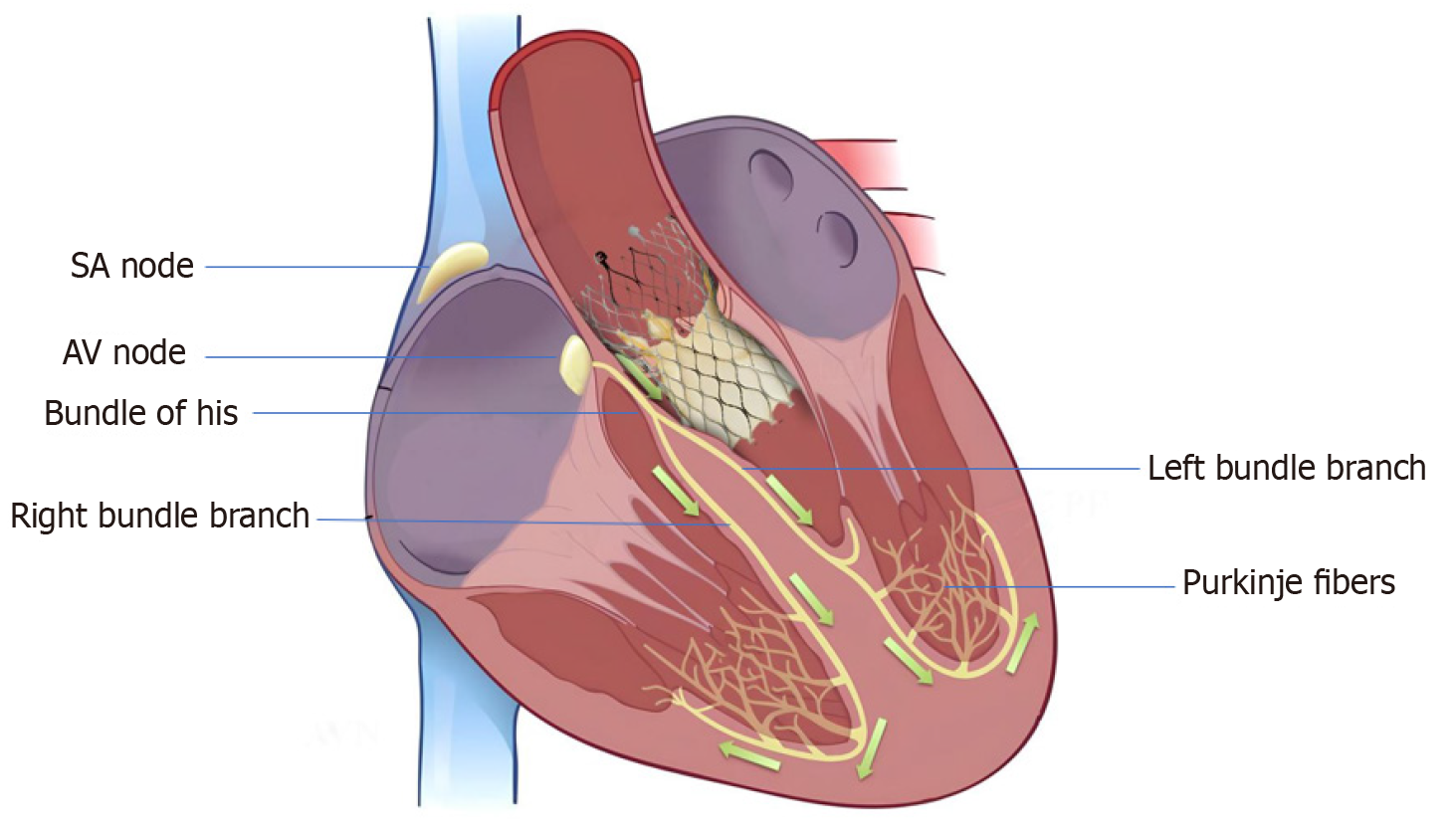

High-grade atrioventricular (AV) block and new-onset left bundle branch block (BBB) are the most common conduction abnormalities that occur after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). However, almost 50% of these may improve with the resolution of perivalvular edema and inflammation post-TAVR. Previous studies have demonstrated that approximately 60%–96% and 2%–7% of patients develop high-degree AV block within 24 and 48 h, respectively[1]. At present, a trend toward early discharge from the hospital post-TAVR (median day 2) has led to an increase in the incidence of permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation post-TAVR. However, the overall rates of PPM implantation within 30 d of TAVR have remained constant (11%) since 2012[2]. Various anatomical, demographic, clinical, electrocardiographic, procedural, and valve-related factors contribute to post-TAVR conduction blocks and have been previously reported. The anatomical proximity of the bundle of His and AV nodes to the aortic valve (Figure 1) and the direct mechanical injury to this conduction system during valve deployment, along with individual variation in the anteroposterior positioning of the AV node and His bundle close to the AV valve, increase the risk of developing post-TAVR heart block[3]. Mitral annular calcifications and calcifications near the device landing zone further increase this risk[4]. In addition, pre-existing electrocardiographic abnormalities, such as right and left BBB, first- and second-degree AV blocks, as well as bifascicular and trifascicular blocks, increase the necessity for PPM implantation during or after the procedure. Anatomically, the left bundle is anterior and closer to the aortic annulus and is prone to injury during valve deployment; this makes pre-existing right BBB among the most significant risk factors[4], aside from the patients’ clinical and demographic traits. A study that analyzed 62083 patients who underwent TAVR from 2012 to 2017 reported that male sex, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, history of atrial fibrillation (AF), renal dysfunction, and dementia were significant predictors of PPM implantation within 30 d post-TAVR[2,5]. Both a history of AF and new-onset AF were found to be independently associated with an increased risk of PPM implantation post-TAVR. A meta-analysis revealed that new-onset AF is associated with mortality, stroke, major bleeding, PPM implantation, and longer in-hospital stay[6]. The use of self-expandable valves (SEV) was also found to pose a higher risk of conduction abnormalities post-TAVR than the use of balloon-expandable valves (BEV). In previous studies, the incidence rate of new-onset left BBB was found to be higher in patients who received a self-expandable CoreValve (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, United States) (27%, range 9%–65%) than those who received the balloon-expandable Sapien valve (Edwards Lifesciences Inc., Irvine, CA, United States) (11%, range 4%–18%)[4]. However, there is a scarcity of data to compare new-generation SEVs with BEVs. A recent trial that compared the two valves demonstrated equivalence for primary valve-related efficacy endpoints of all-cause mortality, stroke, moderate or severe prosthetic valve regurgitation, and PPM implantation within 30 d post-TAVR[7].

Various procedural factors such as transapical access, balloon pre- and post-dilation, prosthesis oversizing (more than 15%–20%), and lower implantation depth also add to the risk (Figure 2)[4].

In a retrospective cohort study published in the journal by Nwaedozie et al[8], patients undergoing TAVR between 2012 and 2019, were followed for 1 year. The effect of baseline DM, supraventricular arrhythmia, and pre-existing nonspecific interventricular conduction delay (QRS duration > 120 ms without any right BBB or left BBB morphology) on the incidence of PPM implantation post-TAVR was analyzed[8]. The study included 357 patients with a mean age of 80 years. Of these patients, 57 (16%) required PPM implantation post-TAVR whereas the remainder did not. With the exception of type 2 DM, which predominated in the pacemaker group, baseline variables such as cardiac risk factors and valve type were similar across the two groups. In this study, the frequency of pacemaker implantation was significantly greater in individuals with pre-existing DM, pre-existing right BBB, QRS duration > 120 ms, and prolonged QTc interval. Furthermore, the incidence of pacemaker implantation continuously increased for every 20-ms increase in duration of baseline QRS segment (above 100 ms). A marginally significant finding was the association between preoperative supraventricular arrhythmia (AF, atrial flutter, junctional rhythm) and a higher incidence of PPM implantation. The association between DM and the risk of PPM implantation post-TAVR was also previously reported, although not extensively studied. The present study reported baseline DM as a significant predictor of pacemaker implantation post-TAVR [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 2.16]. Furthermore, a previous study has reported that pre-existing right BBB and QRS duration > 120 ms predict the need for PPM implantation post-TAVR[4]. However, this study vehemently indicated the increasing OR for the incidence of pacemaker implantation for every 20-ms increase in duration of QRS segment greater than 100 ms. No previous study has demonstrated such a collinear association between QRS duration and an increased risk of PPM implantation post-TAVR. Moreover, only a few studies in the literature have demonstrated the association of pre-existing nonspecific interventricular conduction delay, defined as QRS duration > 120 ms without any right BBB or left BBB morphology, with the risk of PPM implantation post-TAVR. Patients with a longer QTC interval had an OR of 2.94 for PPM placement compared with those with a normal QTc interval due to the collinearity between the QRS and QTc intervals. The authors reported that QTc intervals and PPM implantation did not significantly correlate after stratification by abnormal QRS intervals. In previous studies, a history of AF was found to be consistently associated with the incidence of PPM implantation post-TAVR. However, the present study reported that a history of supraventricular arrhythmia (composite of AF, atrial flutter, and junctional rhythm) is marginally associated with the risk of PPM implantation post-TAVR (P = 0.54), which appears to be a novel finding in the existing literature. This finding in the present study seems to have been driven by a higher number of patients with AF than those with atrial flutter and junctional rhythm in the supraventricular arrhythmia group. Contrary to the existing literature, this study did not show a statistically significant increase in the risk of PPM implantation with SEVs compared with BEVs. The authors owe this to the long experience of operators with SEV in their institution. Additionally, manufacturer-assisted changes in SEV implantation techniques such as usage of cusp overlap technique and shallower implantation of TAVR valve in the left ventricular outflow tract possibly avoid the anatomical proximity with the conduction system during TAVR. The investigators reported a higher incidence of hospitalization for heart failure and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) at 1-year follow-up in the PPM cohort, with no difference in mortality. As this study is a retrospective review conducted in a single center, it might not accurately represent the situation in other geographical areas. Furthermore, the valves were not randomly assigned to the patients according to any predetermined criteria; rather, the assignment was decided by the multidisciplinary TAVR team. Although an equal distribution of valves in both groups was observed, the author claimed that this factor might not have affected the study results. This study supports the existing literature by demonstrating that type 2 DM and baseline right BBB are significant predictors of PPM implantation post-TAVR. For the first time, this study demonstrated a linear association between the incidence of PPM implantation post-TAVR and every 20-ms increase in duration of baseline QRS segment (above 100 ms). Thus, regardless of the side of BBB morphology, patients with a QRS duration above 100 ms are more likely to require permanent PPM implantation post-TAVR. The post-TAVR PPM cohort was also reported to have a higher rate of hospitalization for heart failure and nonfatal MI at 1-year follow-up, although no significant difference in mortality was observed. However, future studies are warranted to validate these findings, and the pathophysiological basis needs to be elucidated.

In summary, this study adds several unique predictors to the existing ones, such as a history of supraventricular arrhythmia and increased QRS duration above 100 ms. Interestingly, the use of SEV in this study did not result in a higher risk of PPM implantation compared with BEV, as previously reported. This could be due to manufacture-assisted changes in SEV implantation techniques, allowing shallow implantation depth. The present study supports the existing literature by demonstrating that type 2 DM and baseline right BBB are significant predictors of PPM implantation post-TAVR.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Heart Association; American College of Cardiology.

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Demola P, Italy; Inoue N, Japan S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Mazzella AJ, Arora S, Hendrickson MJ, Sanders M, Vavalle JP, Gehi AK. Evaluation and Management of Heart Block After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Card Fail Rev. 2021;7:e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Mazzella AJ, Hendrickson MJ, Arora S, Sanders M, Li Q, Vavalle JP, Gehi AK. Shifting Trends in Timing of Pacemaker Implantation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:232-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (18)] |

| 3. | Young Lee M, Chilakamarri Yeshwant S, Chava S, Lawrence Lustgarten D. Mechanisms of Heart Block after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement - Cardiac Anatomy, Clinical Predictors and Mechanical Factors that Contribute to Permanent Pacemaker Implantation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2015;4:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Sammour Y, Krishnaswamy A, Kumar A, Puri R, Tarakji KG, Bazarbashi N, Harb S, Griffin B, Svensson L, Wazni O, Kapadia SR. Incidence, Predictors, and Implications of Permanent Pacemaker Requirement After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:115-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 5. | Abu Rmilah AA, Al-Zu'bi H, Haq IU, Yagmour AH, Jaber SA, Alkurashi AK, Qaisi I, Kowlgi GN, Cha YM, Mulpuru S, DeSimone CV, Deshmukh AJ. Predicting permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: A contemporary meta-analysis of 981,168 patients. Heart Rhythm O2. 2022;3:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | Ryan T, Grindal A, Jinah R, Um KJ, Vadakken ME, Pandey A, Jaffer IH, Healey JS, Belley-Coté ÉP, McIntyre WF. New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:603-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 7. | Thiele H, Kurz T, Feistritzer HJ, Stachel G, Hartung P, Eitel I, Marquetand C, Nef H, Doerr O, Lauten A, Landmesser U, Abdel-Wahab M, Sandri M, Holzhey D, Borger M, Ince H, Öner A, Meyer-Saraei R, Wienbergen H, Fach A, Frey N, König IR, Vonthein R, Rückert Y, Funkat AK, de Waha-Thiele S, Desch S. Comparison of newer generation self-expandable vs. balloon-expandable valves in transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the randomized SOLVE-TAVI trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1890-1899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nwaedozie S, Zhang H, Najjar Mojarrab J, Sharma P, Yeung P, Umukoro P, Soodi D, Gabor R, Anderson K, Garcia-Montilla R. Novel predictors of permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. World J Cardiol. 2023;15:582-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |