Published online Nov 26, 2023. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v15.i11.599

Peer-review started: July 5, 2023

First decision: August 31, 2023

Revised: September 12, 2023

Accepted: November 2, 2023

Article in press: November 2, 2023

Published online: November 26, 2023

Processing time: 141 Days and 3.9 Hours

Heart failure (HF) causes extracardiac organ congestion, including in the hepatic portal system. Reducing venous congestion is essential for HF treatment, but evaluating venous congestion is sometimes difficult in patients with chronic HF. The portal vein (PV) flow pattern can be influenced by right atrial pressure. Ultrasound images of the PV are quite easy to obtain and are reproducible among sonographers. However, the association between PV pulsatility and the condition of HF remains unclear. We hypothesize that PV pulsatility at discharge reflects the condition of HF.

To evaluate the usefulness of PV pulsatility as a prognostic marker for hospitalized patients with acute HF.

This observational study was conducted from April 2016 to January 2017 and April 2018 to April 2019 at Shinko Hospital. We enrolled 56 patients with acute HF, and 17 patients without HF served as controls. PV flow velocity was mea

On admission, the PVPR was significantly higher in patients with acute HF than controls (HF: 0.29 ± 0.20 vs controls: 0.08 ± 0.07, P < 0.01). However, the PVPR was significantly decreased after the improvement in HF (admission: 0.29 ± 0.20 vs discharge: 0.18 ± 0.15, P < 0.01) due to the increase in minimum velocity (admission: 12.6 ± 4.5 vs discharge: 14.6 ± 4.6 cm/s, P = 0.03). To elucidate the association between the PVPR and cardiovascular outcomes, the patients were divided into three groups according to the PVPR tertile at discharge (PVPR-T1: 0 ≤ PVPR ≤ 0.08, PVPR-T2: 0.08 < PVPR ≤ 0.21, PVPR-T3: PVPR > 0.21). The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that patients with a higher PVPR at discharge had the worst prognosis among the groups.

PVPR at discharge reflects the condition of HF. It is also a novel prognostic marker for hospitalized patients with acute HF.

Core Tip: Although reducing venous congestion is essential for heart failure (HF) treatment, the assessment of venous congestion is sometimes difficult, especially in patients with recurrent HF. Interestingly, a previous study demonstrated a correlation between right atrial pressure and portal vein (PV) flow pattern. However, the association between PV flow and the condition of HF remains unclear. Therefore, we investigated the clinical usefulness of PV pulsatility in hospitalized patients with HF. We found that PV pulsatility reflected not only the condition of HF but also cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, PV pulsatility may be a novel prognostic marker for hospitalized patients with HF.

- Citation: Kuwahara N, Honjo T, Sone N, Imanishi J, Nakayama K, Kamemura K, Iwahashi M, Ohta S, Kaihotsu K. Clinical impact of portal vein pulsatility on the prognosis of hospitalized patients with acute heart failure. World J Cardiol 2023; 15(11): 599-608

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v15/i11/599.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v15.i11.599

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) is increasing worldwide, especially in the aging population. Previous studies have reported that patients with HF have more severe frailty and a poorer prognosis than patients with several common diseases, including cancer[1,2]. Therefore, prevention of recurrent acute decompensated HF is of paramount importance.

Extracardiac organ congestion is seen in the advanced stages of chronic HF[3]. When severe right-sided HF is present, liver congestion develops followed by an increase in serum liver aminotransferase and total bilirubin concentrations, indicating a poor prognosis[3]. Thus, reducing venous congestion is essential for HF treatment. However, the assessment of venous congestion is sometimes difficult, especially in patients with recurrent HF.

To evaluate venous congestion, right atrial pressure (RAP) measured by right heart catheterization (RHC) is the most reliable parameter. RHC is difficult to repeat because the process is invasive and costly[4]. For non-invasive assessment, measuring the inferior vena cava (IVC) using ultrasound is the standard method. However, the ultrasound image quality of the IVC is often poor in patients with obesity[4]. Although a previous study reported that intrarenal venous flow has been proposed as venous congestion, reproducible images are difficult to obtain[5]. Therefore, there is a strong demand for a non-invasive and easy-to-use technique for reliable measurement of venous congestion.

The portal vein (PV) is interposed between the capillary network of the splanchnic circulation and the hepatic sinusoids[6]. Ultrasound images of the PV are quite easy to obtain and reproducible among sonographers. Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between RAP and PV flow[7,8]. However, the association between PV flow and the condition of HF remains unclear.

In this study, we aimed to identify the changes in PV flow pattern by the condition of HF and to evaluate the ability of PV pulsatility as a prognostic marker for hospitalized patients with acute HF.

This study was conducted with hospitalized patients with acute HF starting in April 2016, with the total of 56 enrolled by April 2019. The European Society of Cardiology guideline was used to confirm the diagnosis of HF[9]. We also included 17 patients without HF, such as patients with urinary tract infection, dehydration, and other conditions, who were admitted during the same follow-up period as the acute HF patients and who served as controls. Patients in the control group were always in sinus rhythm. We excluded patients with liver cirrhosis, acute coronary syndrome, carbon dioxide narcosis due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a malignant tumor diagnosed in the past 5 years, and renal replacement therapy.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shinko Hospital, and all requirements for written informed consent were waived for the use of the patients’ clinical and imaging data.

All of the patients underwent blood tests and ultrasonography on admission and at discharge. The patients with HF were treated according to current guidelines[9]. The treatment goal was to improve clinical HF symptoms and physical examination findings. The primary endpoint was cardiac death and unexpected re-hospitalization for recurrent HF. The observation period was 1 year from discharge. We investigated the prognosis of all patients by outpatient clinic visit and by telephone conversation.

Ultrasound examinations were performed using ultrasound devices (Vivid S5; GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, United States). Doppler images of PV flow were obtained from right-sided intercostal scanning using a 1.9-6-MHz convex array, and the waveform of PV flow was assessed from the right portal branch (Supplementary Figure 1)[6]. Doppler traces were recorded at the end of expiration. We calculated the PV pulsatility ratio (PVPR) by dividing the difference between the peak velocity and minimum velocity by the peak velocity [(peak velocity - minimum velocity)/peak velocity]. In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), PV velocity was measured for five heartbeats, and the mean value was used for the analysis.

Continuous variables are reported as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables are reported as number and percentage. For comparisons between groups, we used the Student’s t-test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine the stratified composite event-free rates, and the log-rank test was used for comparisons between groups. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc statistical software, version 19.2.6 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium).

Table 1 shows that there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the HF group and the control group, except for age and duration of hospital stay. Among the patients with HF, 32% had a history of HF and 89% had severe symptoms and were classified as New York Heart Association functional class III or IV. Regarding the etiology of HF, 23% of patients with HF had ischemic cardiomyopathy, 25% had non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (including tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and cardiac sarcoidosis), and 20% had valvular heart disease.

| Characteristic | HF | Control | P value |

| No. of patients | 56 | 17 | |

| Age (yr) | 78.1 ± 13.1 | 70.3 ± 12.8 | 0.03 |

| Male | 36 (66) | 12 (70) | 0.85 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.8 ± 4.5 | 24.4 ± 3.7 | 0.18 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 138.9 ± 33.3 | 132.2 ± 26.2 | 0.45 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 84.1 ± 22.3 | 87 ± 21.3 | 0.18 |

| Duration of hospital stay (d) | 16.9 ± 8.5 | 8.1 ± 5.2 | < 0.01 |

| NYHA classification | |||

| Class II | 1 (2) | - | - |

| Class III | 35 (65) | - | - |

| Class IV | 13 (24) | - | - |

| Atrial fibrillation | 29 (51) | 0 (0) | - |

| Etiology of HF | |||

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 13 (23) | - | - |

| Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy | 14 (25) | - | - |

| Valvar heart disease | 11 (20) | - | - |

| Other | 18 (32) | - | - |

| History of HF | 18 (32) | - | - |

| In-hospital death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

PV flow reflects RAP[7,8,10]; therefore, we preliminarily confirmed that the minimum PV velocity was negatively correlated with RAP assessed by RHC (data not shown). As shown in Figure 1A and B, the HF group had a pulsatile PV flow waveform, whereas the control group had a continuous PV flow waveform because of the higher minimum PV velocity, indicating a low RAP. Regarding the PVPR, the control group had a significantly lower PVPR than the HF group (Table 2; control: 0.08 ± 0.07 vs HF: 0.29 ± 0.20, P < 0.01).

| Parameter | Control (admission) | HF (admission) | P value |

| Minimal velocity (cm/s) | 14.4 ± 2.3 | 12.6 ± 4.5 | < 0.01 |

| Peak velocity (cm/s) | 15.7 ± 2.5 | 18.6 ± 6.2 | 0.12 |

| PVPR | 0.08 ± 0.07 | 0.29 ± 0.2 | < 0.01 |

Next, we investigated how AF affected venous congestion in the setting of HF because AF was a major baseline characteristic in the HF group. There were no significant differences in the tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient (TRPG), IVC diameter, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and PVPR at admission between the HF group in sinus rhythm and those with AF (TRPG: 29.8 ± 12.5 mmHg vs 32.3 ± 10.6 mmHg, respectively, P = 0.66; IVC diameter: 15.6 ± 4.1 mm vs 17.5 ± 4.3 mm, respectively, P = 0.15; tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion: 17.9 ± 5.1 mm vs 16.1 ± 3.4 mm, respectively, P = 0.18; PVPR: 0.27 ± 0.19 vs 0.28 ± 0.23, respectively, P = 0.43).

In all patients with HF, clinical symptoms and physical examination findings improved after optimal treatment. At discharge, blood tests showed that total bilirubin and brain natriuretic peptide concentrations were significantly decreased. Transthoracic echocardiography also demonstrated that right heart overload findings, such as the TRPG and IVC diameter, improved significantly after HF treatment (TRPG: 31.3 ± 12.1 mmHg vs 25.2 ± 8.9 mmHg, respectively, P < 0.01; IVC diameter: 16.5 ± 4.2 mm vs 14.2 ± 2.9 mm, respectively, P < 0.01) (Table 3).

| Parameter | Admission | Discharge | P value |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 0.14 |

| AST (IU/L) | 61.4 ± 17.8 | 23.8 ± 15.0 | 0.06 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 46 ± 12.4 | 19 ± 2.0 | 0.06 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | < 0.01 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 28.3 ± 12.1 | 28.4 ± 12.4 | 0.50 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5 ± 1.4 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.30 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 43.7 ± 18.1 | 43.7 ± 18.5 | 0.99 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.8 ± 2.5 | 11.6 ± 2.4 | 0.30 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 1010 ± 1181 | 396 ± 626 | < 0.01 |

| TTE | |||

| EF (%) | 42 ± 16 | 44 ± 14 | 0.51 |

| TRPG (mmHg) | 31.3 ± 12.1 | 25.2 ± 8.9 | < 0.01 |

| TAPSE (mmHg) | 16.5 ± 4.9 | 17.4 ± 3.7 | 0.43 |

| IVC (mm) | 16.5 ± 4.2 | 14.2 ± 2.9 | < 0.01 |

Figure 1B and C depicts the representative PV flow waveforms of patients with HF before and after optimal treatment, respectively. Figure 2 shows the changes in the PVPR from admission to discharge in patients with HF. The PVPR decreased after the improvement in HF (admission: 0.29 ± 0.20 vs discharge: 0.18 ± 0.15, P < 0.01) due to the increase in minimum velocity (admission: 12.6 ± 4.5 cm/s vs discharge: 14.6 ± 4.6 cm/s, P = 0.03). The minimum velocity was negatively correlated with RAP; therefore, RAP also decreased. However, 14% of patients with HF did not demonstrate an improvement in the PVPR, even after HF treatment.

To elucidate the association between the PVPR at discharge and cardiovascular outcomes, we divided the patients with HF into three groups according to the PVPR tertile at discharge (PVPR-T1: 0 ≤ PVPR ≤ 0.08, PVPR-T2: 0.08 < PVPR ≤ 0.21, PVPR-T3: PVPR > 0.21). Surprisingly, the Kaplan–Meier analysis found that patients with a high PVPR at discharge had a significantly worse prognosis than patients with a low PVPR (P < 0.05; Figure 3). There were no significant differences in the biochemical and echocardiographic data among the tertiles (Table 4).

| Parameter | PVPR-T1 | PVPR-T2 | PVPR-T3 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 81.3 ± 11.6 | 78.7 ± 13.7 | 76.6 ± 14.8 | 0.54 |

| Male | 11 (55) | 8 (61) | 14 (56) | 0.92 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 0.84 |

| AST (IU/L) | 24 ± 8.7 | 22.1 ± 6.5 | 25.2 ± 24.5 | 0.85 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 20.6 ± 17.1 | 19.6 ± 11.1 | 17.2 ± 27.4 | 0.86 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.08 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 31.2 ± 13.1 | 24.8 ± 12.2 | 29.0 ± 14.0 | 0.34 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 0.52 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 39.4 ± 15.3 | 48.2 ± 15.6 | 46.9 ± 23.7 | 0.28 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.5 ± 2.4 | 13.0 ± 2.5 | 10.6 ± 2.0 | 0.08 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 200 ± 178 | 350 ± 342 | 682 ± 1030 | 0.12 |

| TTE | ||||

| EF (%) | 48 ± 13 | 42 ± 15 | 42 ± 17 | 0.40 |

| TRPG (mmHg) | 22.1 ± 5.2 | 27 ± 7.3 | 26.1 ± 10.9 | 0.24 |

| TAPSE (mmHg) | 22 ± 5.2 | 22.2 ± 7.5 | 21.9 ± 10.8 | 0.84 |

| IVC (mm) | 13.3 ± 2.6 | 14.7 ± 3.0 | 14.9 ± 3.1 | 0.21 |

In this study, we showed that the PV flow pattern differed between the control group and the HF group. The high PVPR pulsatile pattern was often seen in the HF group but not in the control group. The PVPR was significantly decreased after the improvement in HF and venous congestion. Furthermore, patients with a high PVPR at discharge had a significantly worse prognosis than patients with a low PVPR.

Patients with HF had a high RAP and hepatic venous pressure, representing venous congestion[11]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the PV flow pattern is affected by not only hepatic venous pressure but also RAP[7,8,12,13]. These findings are consistent with our preliminary data showing that the minimum PV velocity was negatively correlated with the RAP assessed by RHC. In this study, patients in the control group had a low PVPR with a high minimum PV velocity, whereas patients with congestive HF had a high PVPR with a low minimum PV velocity at admission. After the improvement in HF, the PVPR was significantly decreased due to the increase in the minimum PV velocity, indicating a decrease in RAP. We also found that there was no significant difference in the PVPR between patients with HF in sinus rhythm and patients with AF. This indicated that there was no correlation between AF and high RAP, which is in agreement with the findings of a previous study[14].

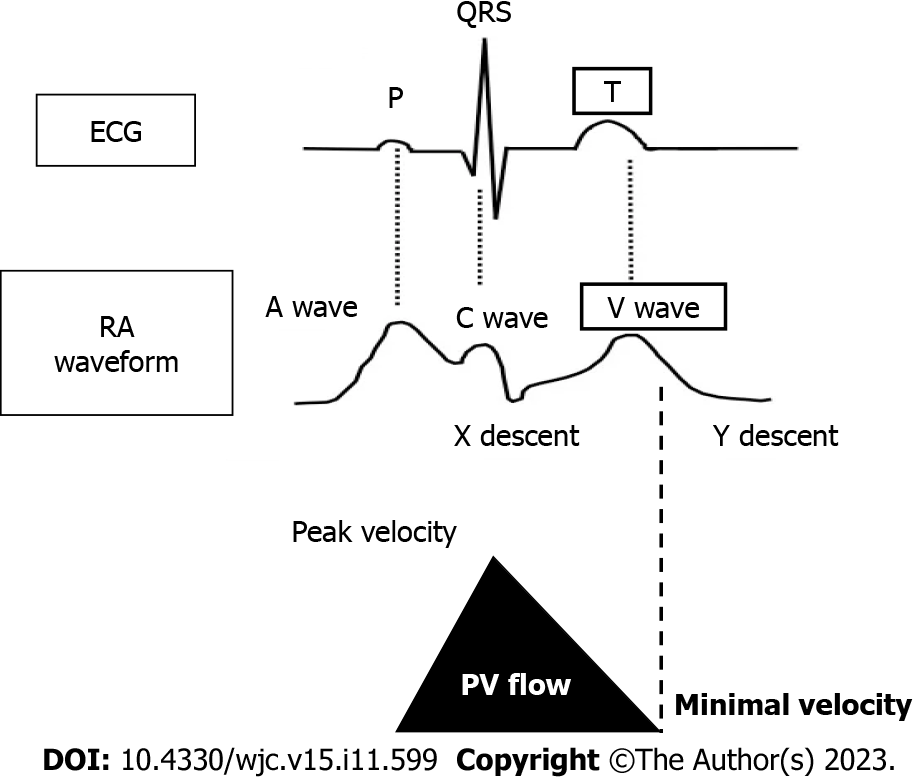

The timing of the minimum PV velocity was synchronized with the peak of the v-wave in the right atrium (RA) (Figure 4). The v-wave represents passive venous filling of the RA when the tricuspid valve is closed. In patients with congestive HF, a high RAP obstructs passive venous blood return into the RA. As a result, we speculate that the velocity of venous blood return from the PV and the IVC decreases. Thus, the minimum PV velocity would be low in patients with congestive HF. When RAP decreases along with HF treatment, the velocity of passive venous return from the PV increases, followed by a continuous PV flow pattern. Given that the PV flow pattern reflects RAP, the PVPR would be a promising marker for evaluating the condition of HF.

The PVPR decreased significantly after HF treatment due to the increase in the minimum PV velocity. However, 14% of the patients with HF did not demonstrate an improvement in the PVPR, even at discharge. In other words, a decrease in the PVPR was not seen in every patient with HF. Given that a high PVPR with a low minimum velocity would indicate a high RAP, we compared the cardiovascular outcomes among the PVPR tertiles. Interestingly, patients with a high PVPR at discharge had a significantly poorer prognosis than patients with a low PVPR (Figure 3). This indicated that patients with a high PVPR still had venous congestion at discharge, even after guideline-based optimal treatment.

IVC diameter and TRPG measurements are standard methods for evaluation for venous congestion and RAP. However, our study demonstrated that the IVC diameter and TRPG did not correlate with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with HF (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). These findings suggest that the PVPR is a simpler and more reliable non-invasive method to identify the condition of HF than traditional measurements.

This study had some limitations. This was a retrospective study that was performed without randomization of patient selection. Moreover, although the two groups of patients demonstrated no significant differences in terms of sex, body mass index, and blood pressure, undetermined factors could have influenced the results.

The PVPR at discharge in hospitalized patients with acute HF reflected venous congestion and the condition of HF. Therefore, the PVPR may be a novel prognostic marker for hospitalized patients with acute HF. We also propose that hospitalized patients with acute HF with a low PVPR at discharge require more careful treatment and close follow-up (Figure 5).

Heart failure (HF) causes extracardiac organ congestion, including in the hepatic portal system. Reducing venous congestion is essential for HF treatment, but evaluating venous congestion is sometimes difficult in patients with chronic HF.

The portal vein (PV) flow pattern can be influenced by right atrial pressure. Ultrasound images of the PV are quite easy to obtain and are reproducible among sonographers. However, the association between PV pulsatility and the condition of HF remains unclear. We hypothesize that PV pulsatility at discharge reflects the condition of HF.

To evaluate the usefulness of PV pulsatility as a prognostic marker for hospitalized patients with acute HF.

This observational study was conducted from April 2016 to January 2017 and April 2018 to April 2019 at Shinko Hospital. We enrolled 56 patients with acute HF, and 17 patients without HF served as controls. PV flow velocity was measured by ultrasonography on admission and at discharge. We calculated the PV pulsatility ratio (PVPR) as the ratio of the difference between the peak and minimum velocity to the peak velocity. The primary endpoint was cardiac death and HF re-hospitalization. The observation period was 1 year from the first hospitalization. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine the stratified composite event-free rates, and the log-rank test was used for comparisons between groups.

On admission, the PVPR was significantly higher in patients with acute HF than controls (HF: 0.29 ± 0.20 vs controls: 0.08 ± 0.07, P < 0.01). However, the PVPR was significantly decreased after the improvement in HF (admission: 0.29 ± 0.20 vs discharge: 0.18 ± 0.15, P < 0.01) due to the increase in minimum velocity (admission: 12.6 ± 4.5 vs discharge: 14.6 ± 4.6 cm/s, P = 0.03). To elucidate the association between the PVPR and cardiovascular outcomes, the patients were divided into three groups according to the PVPR tertile at discharge (PVPR-T1: 0 ≤ PVPR ≤ 0.08, PVPR-T2: 0.08 < PVPR ≤ 0.21, PVPR-T3: PVPR > 0.21). The Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that patients with a higher PVPR at discharge had the worst prognosis among the groups.

The PVPR at discharge reflects the condition of HF.

The PVPR is also a novel prognostic marker for hospitalized patients with acute HF.

We thank Emily Woodhouse, PhD, for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ong H, Malaysia S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Mamas MA, Sperrin M, Watson MC, Coutts A, Wilde K, Burton C, Kadam UT, Kwok CS, Clark AB, Murchie P, Buchan I, Hannaford PC, Myint PK. Do patients have worse outcomes in heart failure than in cancer? A primary care-based cohort study with 10-year follow-up in Scotland. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1095-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Weng SC, Lin CS, Tarng DC, Lin SY. Physical frailty and long-term mortality in older people with chronic heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: a retrospective longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zaghla H, Sabawy ME, Gomma M, Abbass S, Sameea EA. Changes of portal flow inpatients with an acute exacerbation of heart failure and liver congestion. J Med Sci Clin Res. 2015;3:8545-8559. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Szymczyk T, Sauzet O, Paluszkiewicz LJ, Costard-Jäckle A, Potratz M, Rudolph V, Gummert JF, Fox H. Non-invasive assessment of central venous pressure in heart failure: a systematic prospective comparison of echocardiography and Swan-Ganz catheter. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36:1821-1829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Argaiz ER, Rola P, Gamba G. Dynamic Changes in Portal Vein Flow during Decongestion in Patients with Heart Failure and Cardio-Renal Syndrome: A POCUS Case Series. Cardiorenal Med. 2021;11:59-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goncalvesova E, Lesny P, Luknar M, Solik P, Varga I. Changes of portal flow in heart failure patients with liver congestion. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2010;111:635-639. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hu JT, Yang SS, Lai YC, Shih CY, Chang CW. Percentage of peak-to-peak pulsatility of portal blood flow can predict right-sided congestive heart failure. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1828-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Shih CY, Yang SS, Hu JT, Lin CL, Lai YC, Chang CW. Portal vein pulsatility index is a more important indicator than congestion index in the clinical evaluation of right heart function. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:768-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3599-3726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8225] [Cited by in RCA: 7188] [Article Influence: 1797.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoshihisa A, Ishibashi S, Matsuda M, Yamadera Y, Ichijo Y, Sato Y, Yokokawa T, Misaka T, Oikawa M, Kobayashi A, Yamaki T, Kunii H, Takeishi Y. Clinical Implications of Hepatic Hemodynamic Evaluation by Abdominal Ultrasonographic Imaging in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moriyasu F, Nishida O, Ban N, Nakamura T, Sakai M, Miyake T, Uchino H. "Congestion index" of the portal vein. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:735-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ikeda Y, Ishii S, Yazaki M, Fujita T, Iida Y, Kaida T, Nabeta T, Nakatani E, Maekawa E, Yanagisawa T, Koitabashi T, Inomata T, Ako J. Portal congestion and intestinal edema in hospitalized patients with heart failure. Heart Vessels. 2018;33:740-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moriyasu F, Nishida O, Ban N, Nakamura T, Miura K, Sakai M, Miyake T, Uchino H. Measurement of portal vascular resistance in patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fletcher AJ, Robinson S, Rana BS. Echocardiographic RV-E/e' for predicting right atrial pressure: a review. Echo Res Pract. 2020;7:R11-R20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |