Published online Apr 26, 2022. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v14.i4.260

Peer-review started: October 29, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 5, 2022

Accepted: March 15, 2022

Article in press: March 15, 2022

Published online: April 26, 2022

Processing time: 171 Days and 4.8 Hours

Mechanical complications are a rare presentation in chronic coronary syndromes, which have significantly decreased in the primary coronary intervention era. Incomplete rupture may occur, resulting in pseudoaneurysms (PANs). Early reperfusion decreases the risk of this complication. Echocardiography is the method of choice for diagnosis.

A 54-year-old female hypertensive patient, with a history of non-revascularized inferior and anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (MI) 4 years prior, was admitted to the cardiac unit of the hospital with complaints of abdominal pain and dyspnea lasting 2 mo. The patient was hemodynamically stable, and 12-lead electrocardiogram showed persistent ST elevation and Q wave in the inferior and apical regions. Transthoracic echocardiogram in the two-chamber view showed a narrow neck of a wide PAN in the distal apical left ventricular inferior wall. In addition, the apical four-chamber and subcostal views revealed a second bulky PAN of the apical wall separated from the first by a common organizing thrombus. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the coexistence of more than one PAN. The patient received conservative medical treatment, and surgery was scheduled for outside the country. The patient had worsening multiple organ failure and died 4 wk after presentation.

Multifocal PANs rarely occur in chronic MI. Attention should be paid to patients with pain and cardiovascular risk factors.

Core Tip: Multiple left ventricular pseudoaneurysms are a rare complication following myocardial infarction (MI), which can be diagnosed years after the infarction. This case highlights the ultimate importance of appropriate early reperfusion of MI and the role of echocardiography and multimodal imaging for the diagnostic assessment of this lethal condition.

- Citation: Jallal H, Belabes S, Khatouri A. Uncommon post-infarction pseudoaneurysms: A case report. World J Cardiol 2022; 14(4): 260-265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v14/i4/260.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v14.i4.260

Left ventricular (LV) pseudoaneurysms (PANs) are rare mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction (MI). They are caused by rupture of the free wall, are composed of organizing thrombus due to hemorrhage into the pericardial space after cardiac rupture (CR), and involve various amounts of epicardium and parietal pericardium. As stated by Hung et al[1], “PAN following transmural infarction has a high mortality rate of up to 20%”. There have been few reports of LV PAN during the chronic phase of MI, and among them all have had a single localization. Although surgical repair is the treatment of choice, transcatheter intervention for PAN repair is feasible in selected cases.

Herein, we present the first case of uncommon CR manifested as multiple adjacent LV PANs, which occurred in a female patient with a history of MI.

A 54-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain and dyspnea.

The patient presented with recurrent episodes of epigastric pain and dyspnea, which began 2 mo prior and worsened 48 h before hospital admission.

The patient had a long history of untreated and advanced hypertension, as well as a history of inferior and anterior ST-segment elevation MI without revascularization, which had occurred 4 years prior.

The patient had no relevant family history.

The patient presented with hemodynamic stability, a heart rate of 96 beats/min, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air of 98%. Symptoms of acute heart failure were excluded by clinical cardiological examination. A painful and hard epigastric mass was detected upon abdominal examination.

Blood analysis revealed mild leukocytosis (12 × 109/L), with neutrophil predominance (80%) and normal hematocrit and platelet levels. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal, and troponin T was slightly increased at 1.2 ng/mL. Blood creatinine was increased at 435 mmol/L. The 12-lead electrocardiogram showed persistent ST elevation and Q wave in the inferior and apical territory. Chest X-ray revealed increased cardiothoracic ratio with rounded opacity along the left cardiac silhouette.

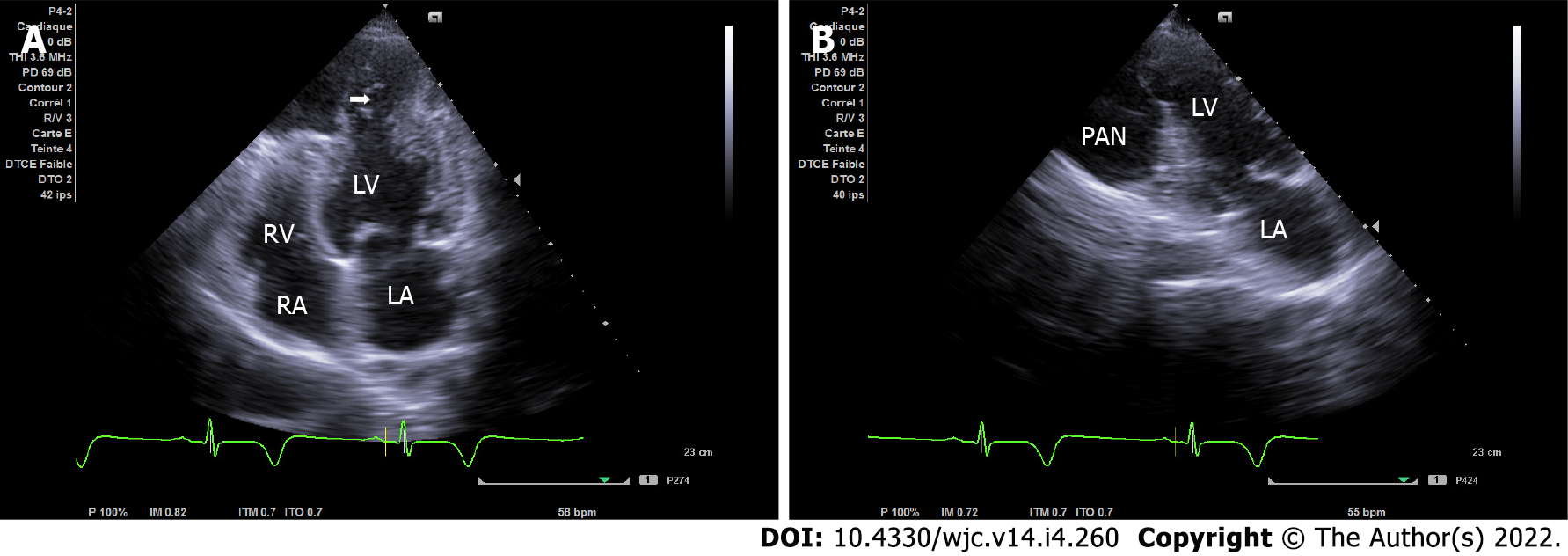

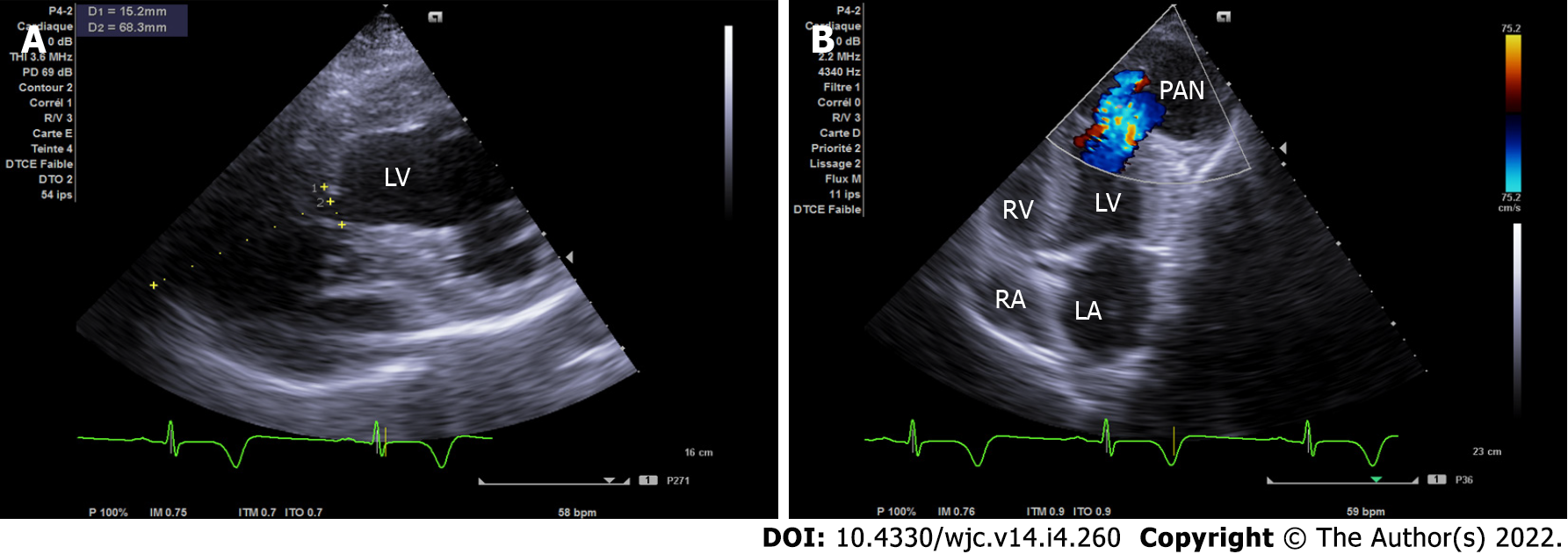

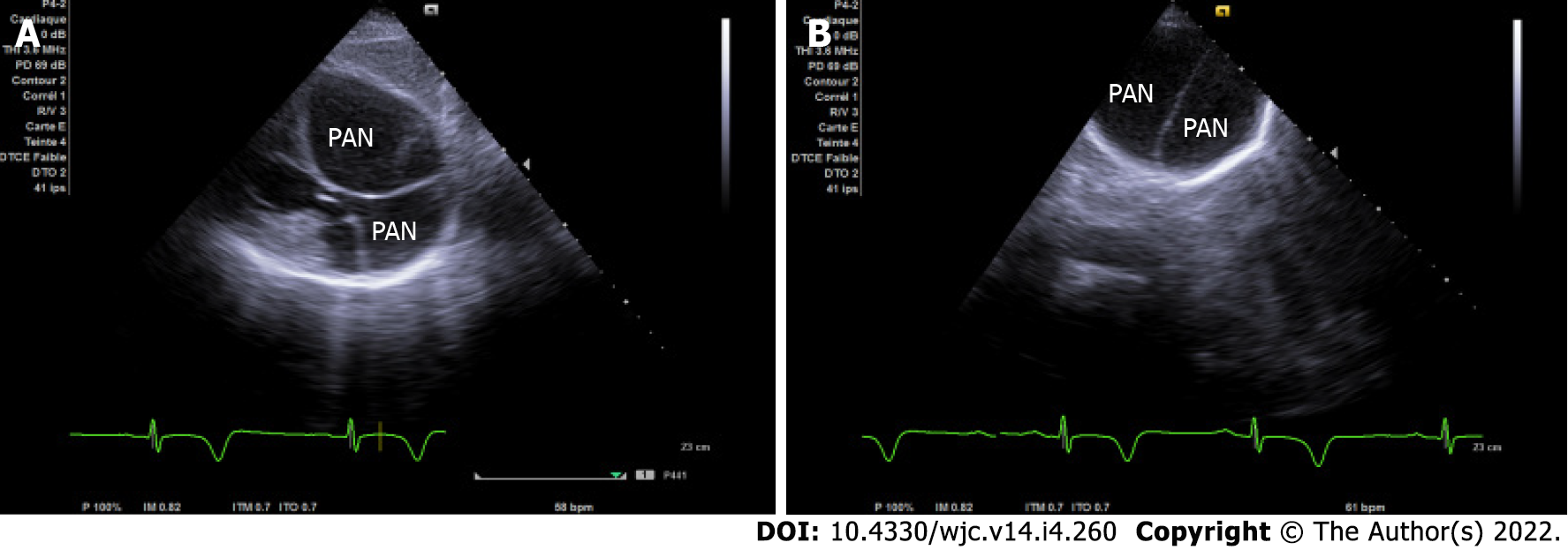

Echocardiography is the first test performed after admission because of its availability. In the four-chamber view, initial imaging evaluation with transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed the narrow neck of a large PAN in the LV apical wall (arrow) (Figure 1A), in the apical two-chamber view (Figure 1B) and modified short axis view (Figure 2A). TTE revealed a second PAN of the distal apical inferior wall, separated from the first PAN by a common organizing fibrous tissue, as detected in the subcostal view (Figure 3A) and apex view (Figure 3B), without pericardial effusion. Color Doppler imaging in the four-chamber view (Figure 2B) demonstrated flow in and out of the pericardial cavity at the site of the tear, as well as abnormal flow into the PAN without any shunt through the organizing thrombus. The LV communicated with the PAN via a narrow neck formed by the ruptured apical and inferior myocardium. The dimensions of the cavity (68/15 mm; Figure 2A) and imaging findings were indicative of a PAN; however, it is of great clinical importance to differentiate PANs, which have a high likelihood of spontaneous rupture, from a true aneurysm, which seldom ruptures.

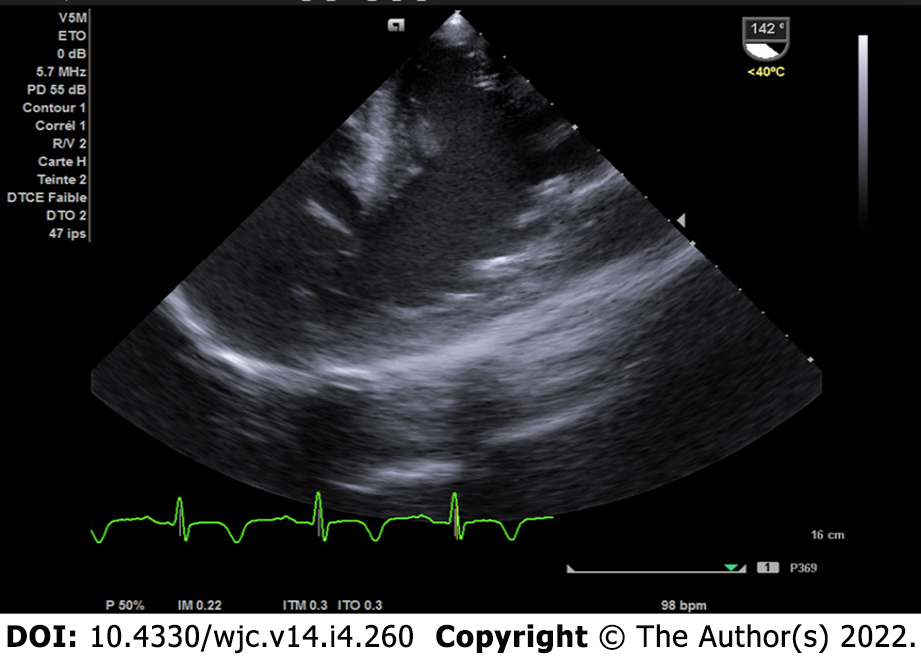

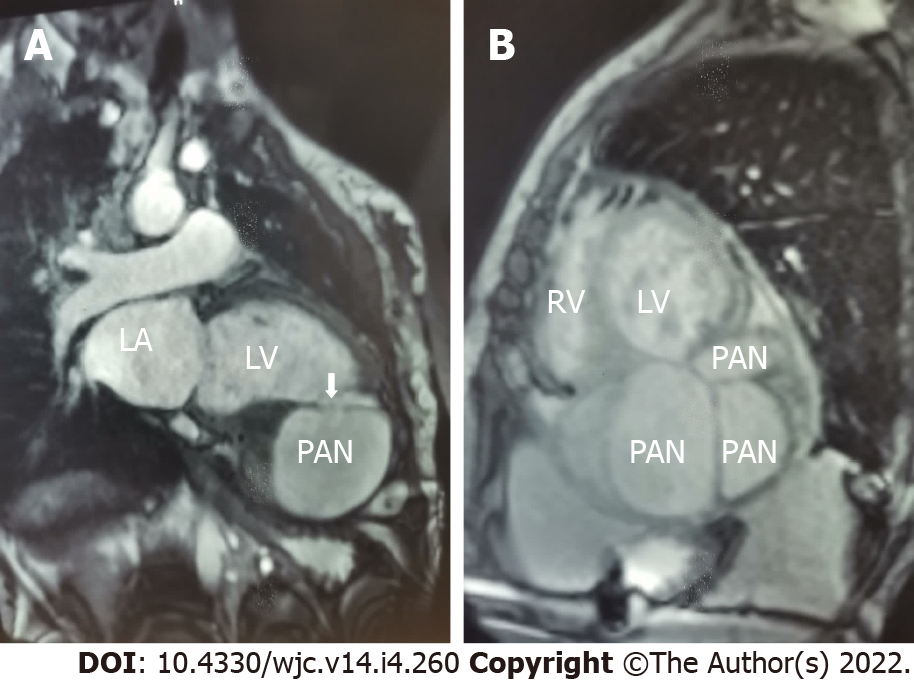

The patient was further evaluated with transesophageal echocardiogram, despite the difficulty in assessing the apical wall by this approach; however, the left ventricle communicated with the PANs via a narrow neck formed by the ruptured apical and inferior myocardium (Figure 4). To better characterize this finding, a cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) scan was performed since the severe chronic renal failure precluded evaluation by thoracic computed tomography angiography and to take advantage of the good non-invasive tissue characterization offered by CMR; the cine sequence images confirmed severe LV dysfunction and showed an apical PAN without an intracavitary thrombus in the two-chamber view (Figure 5A). Curiously, a larger and a small outpouching, separated by fibrous tissue, was revealed in the inferior apical wall (Figure 5B); the outpouchings were seen to be associated with disrupted myocardial wall, and they were surrounded only by pericardium.

Multiple adjacent LV PANs following chronic MI.

The patient was immediately started on conservative medical treatment, including a curative anticoagulant (acenocoumarolum at 4 mg/d), diuretic (furosemide at 40 mg/d), heart failure therapeutics (bisoprolol at 5 mg and ramipril 5 mg, both one pill per day) and coronary heart disease therapeutics (aspirin at 75 mg/d and atorvastatin at 20 mg/d). After collegial discussion among the care team, the decision was made to proceed with surgical repairs outside the country due to the lack of a cardiac surgery center.

The patient had an uneventful clinical course with medical treatment; surgery was delayed considering the suspension of air travel due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. The patient had multiple organ failure caused by acute free intrapericardial rupture, which usually causes cardiac tamponade and death, and died 4 wk after presentation.

PAN is a contained progressive rupture of the LV free wall. It is commonly caused by MI but may also occur after cardiac surgery, chest trauma or infection, and endocardial electrophysiologic procedures; “although in some cases the etiology may be unknown[2]”. Typically, LV PANs can also be identified by echocardiography and are typified by a PAN cavity that communicates with the LV chamber via a very narrow neck and frequently contains a thrombus. The characteristic to-and-fro blood flow through the site of rupture can be detected with Doppler and color flow imaging; however, “magnetic resonance imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis if echocardiography findings are atypical[3]”. While most PANs are located in the inferoposterior or inferolateral region, “some studies have concluded that the most typical location is the anterior or lateral wall[4].

In the last several years, the incidence of CR has decreased with the development of “primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI), which has been an important protective factor[5]”. Risk factors include advanced age, female sex, first infarction, large infarction, and delivery of fibrinolytic therapy more than 14 h after the onset of symptoms. Our patient was in the 5th decade of life, female sex, and hypertensive, with an untreated large anterior MI. Hence, our patient was at high risk of developing CR. “Early reperfusion and the presence of collateral circulation, which limit the extent of myocardial tissue damage, decrease the risk of free wall rupture[6]”.

To the best of our knowledge, the presented case is the first in the literature to show more than one PAN caused by MI with long-term evolution. In this case, the onset and progression were possibly influenced by the large extension of non-revascularized MI, and the severity of hypertension explained by the advanced stage of chronic kidney failure. The first evaluation by echocardiography in the early phase of acute MI did not show the development of dyskinesia or aneurysm. In acute LV PAN, once the diagnosis is confirmed, surgical repair is the preferred treatment, although conservative medical treatment for certain high-risk patients may be associated with a good outcome, “as has been described in some retrospective studies showing that patients with an incidental finding of chronic small LV PAN, less than 3 cm in size, and patients with increased surgical risk can be managed conservatively[7]”. However, the preferred approach remains surgical management. Our patient was primarily treated by medical treatment and was scheduled for surgery after discussion with the surgical team, but she died after 4 wk from acute free intrapericardial rupture, in accordance with the literature showing that “PANs have a high risk of rupture, occurring in 30% to 45% of cases[8]”. In patients treated conservatively, some complications may occur, such as thromboembolism, compression of adjacent structures, and infection.

PANs are caused by rupture of the myocardial wall and are an infrequent complication of acute MI that rapidly leads to death. However, some cases may take a subacute or chronic course when a small rupture is temporarily sealed by fibrinous pericardial adhesions or thrombus. No cases of multiple PANs of LV have been reported. The best weapon against this lethal complication is timely pharmacologic or mechanical reperfusion.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Gabon

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bairwa DBL, India; Wang Y, China S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Hung MJ, Wang CH, Cherng WJ. Unruptured left ventricular pseudoaneurysm following myocardial infarction. Heart. 1998;80:94-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ashraf T, Aziz R, Khuwaja AM. Left ventricular aneurysmectomy in a young female with pseudoaneurysm of unknown etiology. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2020;32: 110-113. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Caldeira A, Albuquerque D, Coelho M, Côrte-Real H. Left Ventricular Pseudoaneurysm: Imagiologic and Intraoperative Images. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e009500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abdelnaby M, Al-Maghraby A, Saleh Y, El-Amin A, Hammad B. Post-Myocardial Infarction Left Ventricular Free Wall Rupture: A Review. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2017;. |

| 5. | Honda S, Asaumi Y, Yamane T, Nagai T, Miyagi T, Noguchi T, Anzai T, Goto Y, Ishihara M, Nishimura K, Ogawa H, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Yasuda S. Trends in the clinical and pathological characteristics of cardiac rupture in patients with acute myocardial infarction over 35 years. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sulzgruber P, El-Hamid F, Koller L, Forster S, Goliasch G, Wojta J, Niessner A. Long-term outcome and risk prediction in patients suffering acute myocardial infarction complicated by post-infarction cardiac rupture. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:399-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yeo TC, Malouf JF, Oh JK, Seward JB. Clinical profile and outcome in 52 patients with cardiac pseudoaneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Frances C, Romero A, Grady D. Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:557-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |