Published online Dec 26, 2022. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v14.i12.640

Peer-review started: August 28, 2022

First decision: October 24, 2022

Revised: November 2, 2022

Accepted: November 30, 2022

Article in press: November 30, 2022

Published online: December 26, 2022

Processing time: 113 Days and 7.7 Hours

Home telemonitoring has been used as a modality to prevent readmission and improve outcomes for patients with heart failure. However, studies have produced conflicting outcomes over the years.

To determine the aggregate effect of telemonitoring on all-cause mortality, heart failure-related mortality, all-cause hospitalization, and heart failure-related hospitalization in heart failure patients.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 home telemonitoring randomized controlled trials involving 14993 patients. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of telemonitoring duration, recent heart failure hospitalization, and age on telemonitoring outcomes.

Our study demonstrated that home telemonitoring in heart failure patients was associated with reduced all-cause [relative risk (RR) = 0.83, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.75-0.92, P = 0.001] and cardiovascular mortality (RR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.54-0.81, P < 0.001). Additionally, telemonitoring decreased the all-cause hospitalization (RR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.80-0.94, P = 0.002) but did not decrease heart failure-related hospitalization (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.77-1.01, P = 0.066). However, prolonged home telemonitoring (12 mo or more) was associated with both decreased all-cause and heart failure hospitalization, unlike shorter duration (6 mo or less) telemonitoring.

Home telemonitoring using digital/broadband/satellite/wireless or blue-tooth transmission of physiological data reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in heart failure patients. In addition, prolonged telemonitoring (≥ 12 mo) reduces all-cause and heart failure-related hospitalization. The implication for practice is that hospitals considering telemonitoring to reduce heart failure readmission rates may need to plan for prolonged telemonitoring to see the effect they are looking for.

Core Tip: Home telemonitoring has been used as a modality to prevent readmission and improve outcomes for patients with heart failure. However, studies have produced conflicting outcomes over the years. This meta-analysis aims to determine the aggregate effect of telemonitoring on all-cause mortality, heart failure-related mortality, all-cause hospitalization, and heart failure-related hospitalization in heart failure patients. This study found that home telemonitoring using digital/broadband/satellite/wireless or blue-tooth transmission of physiological data reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in heart failure patients. Additionally, prolonged home telemonitoring (12 mo or more) led to both decreased all-cause and heart failure hospitalization, unlike shorter duration (6 mo or less) telemonitoring. The implication for practice is that hospitals considering telemonitoring to reduce heart failure readmission rates may need to plan for prolonged telemonitoring to see the effect they are looking for.

- Citation: Umeh CA, Torbela A, Saigal S, Kaur H, Kazourra S, Gupta R, Shah S. Telemonitoring in heart failure patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Cardiol 2022; 14(12): 640-656

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v14/i12/640.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v14.i12.640

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome in which patients develop signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, fatigue, and/or fluid retention due to cardiac dysfunction or abnormality in cardiac structure[1]. Heart failure is classified as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (EF) (< 40%), heart failure with mildly reduced EF (41% to 49%), or heart failure with preserved EF (> 50%)[1]. Heart failure has become the primary cause of hospitalization in the United States in the elderly[2,3]. The prevalence increases with increasing age, and affected individuals significantly consume healthcare resources. It has significant public health implications, with an estimated cost of about $30.7 billion in the United States in 2012, with the projected total rise in cost up to $69.7 billion by 2030[2,4]. Additionally, heart failure is associated with high morbidity and mortality, with a readmission rate during six months following discharge as high as 50%[5]. Heart failure is not just a problem in the United States but a global disease, with its prevalence increasing across the globe[1,2].

As the survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction improves and with a population that continues to age, we will continually see a rise in patients with heart failure and, thus, more rehospitalizations. Various modalities have been in the works to improve outcomes for patients with heart failure to prevent readmission. One of these modalities, termed home telemonitoring, involves tracking patients’ health status using electronic devices at home[6-10]. Healthcare providers can obtain patients’ vital signs, weight, and other parameters recorded and transmitted through communication technology and contact the patients if abnormalities are noted. In this way, deteriorations in patients’ conditions are detected early, resulting in early interventions. A review of randomized controlled trials of noninvasive home telemonitoring compared to standard practice for people with heart failure has shown a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, heart failure-related hospitalizations, and improvement in quality of life and heart failure knowledge and self-care behaviors in some studies[6].

Though using home telemonitoring to monitor patients remotely has been going on for a while, further evaluation is needed as studies have reported inconsistent results over the years. While telemonitoring was beneficial in reducing hospital admission, all-cause mortality, and emergency room visits in some studies, others did not show such benefits[7-10]. These differences in outcomes from multiple studies suggest that careful analysis of study outcomes is needed to determine its aggregate benefit to heart failure patients. This meta-analysis aims to determine the aggregate effect of telemonitoring on all-cause mortality, heart failure-related mortality, all-cause hospitalization, and heart failure-related hospitalization in heart failure patients. We also conducted sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of telemonitoring duration, recent heart failure hospitalization, and age on telemonitoring outcome.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis was designed according to the guidelines included in the PRISMA statement[11].

Our primary outcomes were all-cause and heart failure-related mortality and all-cause and heart failure-related hospitalizations.

We included only randomized controlled trials of home telemonitoring in heart failure patients that reported mortality or readmissions as the outcome measure. We defined home telemonitoring as patients self-measuring their vital signs (such as pulse, weight, blood pressure) at home and using a digital/broadband/satellite/wireless or blue-tooth device to transmit the data to healthcare professionals. The healthcare professionals reviewed the transmitted data and instructed the patient on the next steps if the values were abnormal, including medication adjustment. We excluded studies not written in English. Two authors independently reviewed the abstracts after our literature search to assess if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria to be included in the study.

Articles were obtained by searching the PubMed, Embase, Google scholar, Reference Citation Analysis and Cochrane databases with the term heart failure, combined with the following terms: “telemonitoring”, “telehealth”, “home monitoring”, and “remote monitoring”. In PubMed and Embase, we used a filter to limit our search to randomized controlled trials conducted between January 1, 2000, and September 2021. In the Google scholar search, we restricted the search to the article titles that contain the search terms.

Information on study participants, methods, interventions, and outcomes, including hospitalization and death, was extracted onto a data-sheet in Excel (Microsoft Corporation, 2018). We reported only the result of the heart failure patients for articles that included heart failure patients and patients with other illnesses but reported separate results.

We assessed the risk of bias using the methods presented in the Cochrane handbook[12]. First, the risk of bias was evaluated independently by two authors. In case of disagreement between the two authors, the matter was discussed and decided by consensus. The presence of publication bias for each outcome was assessed using funnel plots.

The study’s primary endpoints are the effect of telemonitoring on all-cause mortality, heart failure-related mortality, all-cause hospitalization, and heart failure-related hospitalization in heart failure patients. We calculated the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each outcome in each study. We used the random effect model and tested the null hypothesis using Z-score. A P value of < 0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant. We tested heterogeneity in study outcomes using the χ2 test and the I2 statistic.

To assess the outcomes in different sub-groups, we performed a series of subgroup analyses: (1) Comparison of cumulative outcomes in the telemonitoring and usual care approach, according to the duration of follow-up (≤ 6 mo and ≥ 12 mo). The median and modal duration of follow-up in the studies was six months, and most of the studies that extended beyond six months lasted for at least 12 mo. Thus, we decided to compare studies with a duration of ≤ 6 mo with those ≥ 12 mo; (2) Comparison of cumulative outcomes in the telemonitoring and usual care approach, in studies of patients with recent heart failure hospitalization, which we defined as heart failure hospitalization within six weeks before the study, and those that did not; and (3) Comparison of cumulative outcomes in the telemonitoring and usual care approach, in studies that recruited patients ≥ 65 years. The analysis was done using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.

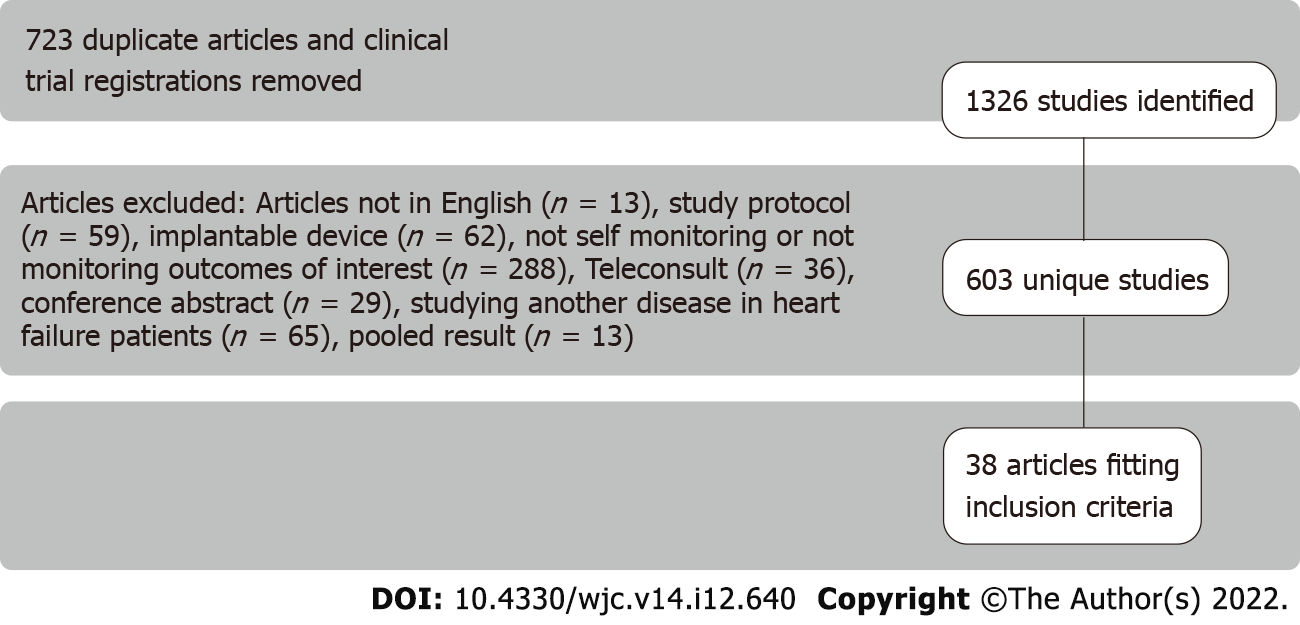

Our search produced 1326 articles, of which 603 were unique articles after removing duplicate publications and clinical trial registrations. Two researchers independently reviewed the 603 abstracts to assess if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the review. We excluded papers not in English (n = 13), papers that used implantable devices such as pacemakers (n = 62), papers on telemonitoring study protocol (n = 59), papers on teleconsulting (n = 36), conference abstracts (n = 29), papers that did not measure heart failure patients’ hospitalization or mortality or did not include self-monitoring (n = 288), papers studying another disease in heart failure patients (n = 65), and papers that joined the results of patients with heart failure and patients with other illnesses (n = 13) (Figure 1).

Our study included 38 randomized controlled trials on telemonitoring in heart failure patients between January 1, 2000, and October 3, 2021[7-10,13-46] (Table 1). Fourteen thousand nine hundred and ninety-three patients were recruited in the 38 studies, with a mean of 394 and a range of 48 to 1653. The mean duration of the studies was 9.4 mo and a range of 1 to 32 mo in Table 1. Forty-seven percent of the studies were done in North America (the United States of America and Canada), and the majority of the remaining were done in Europe. All the studies involved patients measuring their vital signs and weight and using digital/broadband/satellite/wireless or blue-tooth to transmit the data to the healthcare providers. The patients transmitted their data daily in 92% of the studies and weekly in 8% of studies (Table 1). The nurses were the primary healthcare professionals that monitored the patients’ data and informed the physicians of abnormal values in 79% of the studies. They also contacted the patient if there were abnormal values with instructions on what to do next. Physicians led the process in 6 studies (16%), where the physicians reviewed the transmitted patients’ data and contacted them if values were abnormal with instructions on what to do next. A case manager led the process in one of the studies, and a non-clinician led one study (Table 1).

| Ref. | Number of patients | Duration of follow-up (mo) | Country | Person responsible for monitoring telemedicine data | Frequency of measuring and transmitting vital signs | Frequency of clinicians reviewing data | Included telemonitoring patients’ education | Included control group patient education | Recruited patients ≥ 65 yr | Recruited recently discharged patients | Recruited frequently hospitalized patients |

| Nouryan et al[15], 2019 | 89 | 6 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Seto et al[16], 2012 | 100 | 6 | Canada | Physician | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Weintraub et al[17], 2010 | 188 | 3 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Blum and Gottlieb[18], 2014 | 156 | 27 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dansky et al[19], 2008 | 284 | 4 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kashem et al[20], 2008 | 48 | 12 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Benatar et al[21], 2003 | 216 | 12 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Pedone et al[22], 2015 | 96 | 6 | Italy | Physician | Daily | Daily | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Wade et al[23], 2011 | 316 | 6 | United States | Case manager | Daily | Daily | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Comín-Colet et al[24], 2016 | 178 | 6 | Spain | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Olivari et al[25], 2018 | 339 | 12 | Italy | Non-clinician | Daily | Daily | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Lyngå et al[26], 2012 | 319 | 12 | Sweden | Nurse | Daily | 3 d a week | No | No | No | No | No |

| Scherr et al[27], 2009 | 120 | 6 | Austria | Physician | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Antonicelli et al[28], 2008 | 57 | 12 | Italy | Nurse | Weekly | Weekly | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Giordano et al[29], 2009 | 460 | 12 | Italy | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ong et al[30], 2016 | 1437 | 6 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Kalter-Leibovici et al[10], 2017 | 1360 | 32 | Isreal | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Mortara et al[31], 2009 | 461 | 12 | United Kingdom, Poland, and Italy | Nurse | Weekly | Weekly | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dar et al[32], 2009 | 182 | 6 | United Kingdom | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Vuorinen et al[33], 2014 | 94 | 6 | Finland | Nurse | Weekly | Weekly | No | No | No | No | No |

| Goldberg et al[34], 2003 | 280 | 6 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Soran et al[35], 2008 | 315 | 6 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Chaudhry et al[36], 2010 | 1653 | 6 | United States | Physician | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Koehler et al[13], 2018 | 1571 | 12 | Germany | Physician | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Cleland et al[14], 2005 | 418 | 8 | Germany, Netherlands, and United Kingdom | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Koehler et al[7], 2011 | 710 | 26 | Germany | Physician | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kotooka et al[8], 2018 | 181 | 15 | Japan | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Pekmezaris et al[9], 2019 | 104 | 3 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Villani et al[37], 2014 | 80 | 12 | Italy | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dendale et al[38], 2012 | 160 | 6 | Belgium | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Woodend et al[39], 2007 | 121 | 3 | Canada | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Galinier et al[40], 2020 | 937 | 18 | France | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Capomolla et al[41], 2004 | 133 | 12 | Italy | Nurse | Daily | Daily | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kulshreshtha et al[42], 2010 | 150 | 6 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Kenealy et al[43], 2015 | 98 | 6 | New Zealand | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dawson et al[44], 2021 | 1380 | 1 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Delaney et al[45], 2013 | 100 | 3 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | No | No | No |

| Schwarz et al[46], 2008 | 102 | 3 | United States | Nurse | Daily | Daily | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

There was a low risk of bias in the randomization process, measurement of outcome data, or missing outcome data in the studies included in the meta-analysis. However, the intervention was not blinded in any of the primary studies because of the nature of the studies. Additionally, many of the studies did not provide information on whether outcome assessors were aware of the intervention received by study participants. Thus, it is unclear how these affected the study outcomes. Furthermore, many studies did not indicate if the data was analyzed per a pre-specified plan that was finalized before unblinded outcome data were available for analysis. Thus, we did not have information to assess the risk of bias in selecting the reported result. Table 2 shows the bias assessment in each of the primary studies. The heterogeneity within the studies ranged from low (for cardiovascular mortality, I2= 0%) to substantial (for all-cause hospitalizations, I2= 69%). The funnel plots did not show any major publication bias in the primary outcomes assessed (Supplementary Figures 1-3).

| Ref. | The allocation sequence was random | The allocation sequence was adequately concealed | Participants aware of their assigned intervention | Interventions implementors were aware of participants’ assigned groups | Outcome data were available for all, or nearly all, participants randomized | Outcome measurement could have differed between groups | Outcome assessors were aware of the intervention received by participants | Data analysis plan was finalized before data were available for analysis |

| Nouryan et al[15], 2019 | Yes | Probably yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Seto et al[16], 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Weintraub et al[17], 2010 | Probably yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Blum and Gottlieb[18], 2014 | Probably yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Dansky et al[19], 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Kashem et al[20], 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Benatar et al[21], 2003 | Probably yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Probably yes | No | No information | No information |

| Pedone et al[22], 2015 | Probably yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Wade et al[23], 2011 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information | No information |

| Comín-Colet et al[24], 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information |

| Olivari et al[25], 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | Yes |

| Lyngå et al[26], 2012 | Probably yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Scherr et al[27], 2009 | Probably yes | No information | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information | No information |

| Antonicelli et al[28], 2008 | Probably yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Probably yes | No | No information | No information |

| Giordano et al[29], 2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Ong et al[30], 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Probably yes | No | No | Yes |

| Kalter-Leibovici et al[10], 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Mortara et al[31], 2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Dar et al[32], 2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Vuorinen et al[33], 2014 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Goldberg et al[34], 2003 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information | No information |

| Soran et al[35], 2008 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Chaudhry et al[36], 2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Koehler et al[13], 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | Yes |

| Cleland et al[14], 2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | Yes |

| Koehler et al[7], 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | Yes |

| Kotooka et al[8], 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Pekmezaris et al[9], 2019 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Villani et al[37], 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Dendale et al[38], 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information |

| Woodend et al[39], 2007 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Galinier et al[40], 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Capomolla et al[41], 2004 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information | No information |

| Kulshreshtha et al[42], 2010 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information | No information |

| Kenealy et al[43], 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information |

| Dawson et al[44], 2021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No information | No information |

| Delaney et al[45], 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

| Schwarz et al[46], 2008 | Yes | No information | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No information | No information |

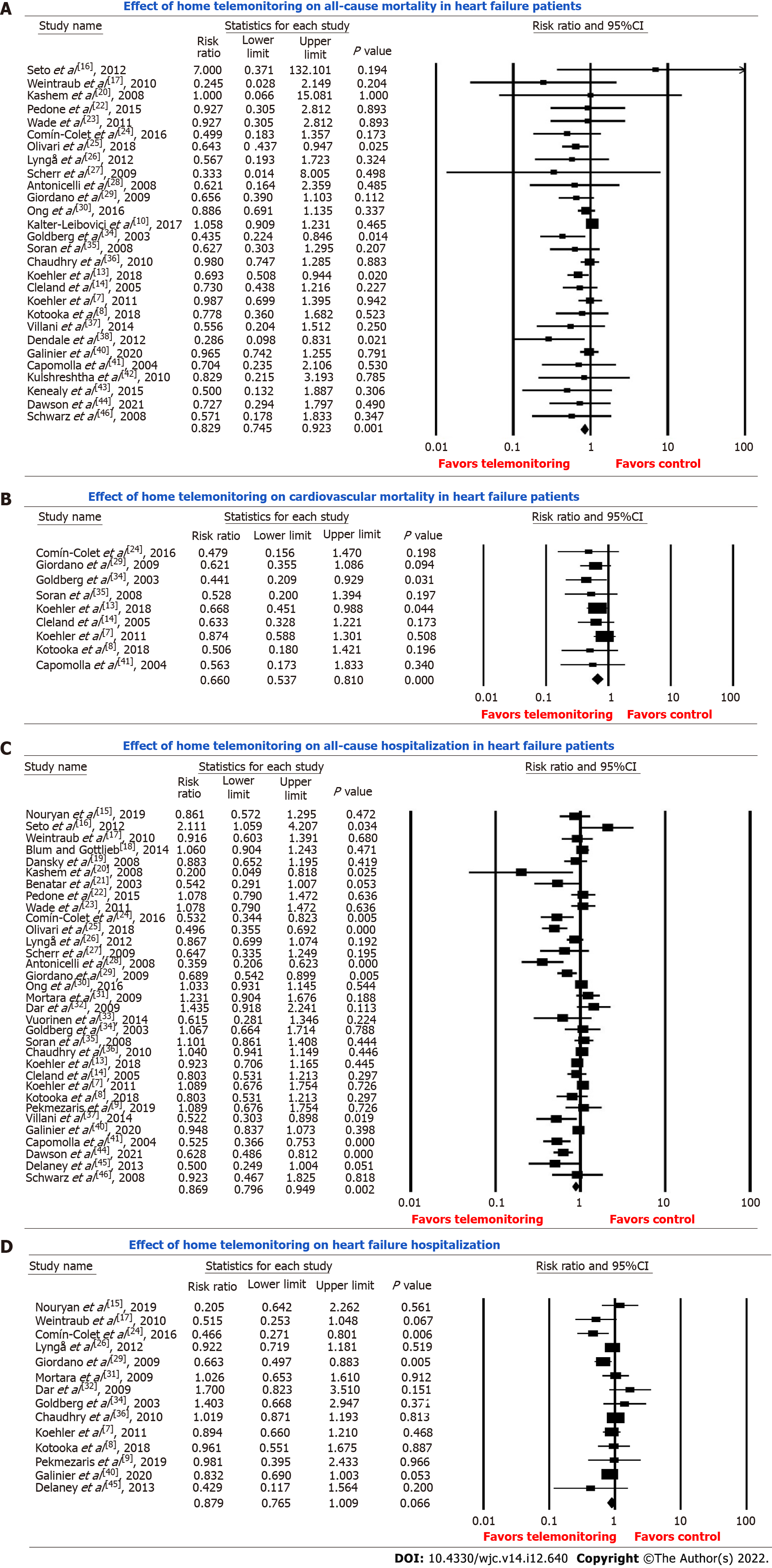

The pooled estimate of the effect of telemonitoring on all-cause death in comparison with standard care in 28 studies with 13188 patients showed that telemonitoring was associated with reduced all-cause mortality in heart failure patients (RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.75-0.92, P = 0.001) (Figure 2A). Our sensitivity analysis showed that the duration of telemonitoring did not influence all-cause mortality in heart failure patients. Analysis of 15 studies of six months or less duration showed reduced all-cause mortality (RR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.65-0.94, P = 0.009). Similarly, analysis of 12 studies of 12 mo or more months duration also showed reduced all-cause mortality (RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.74-0.99, P = 0.032) (Table 3).

| All-cause mortality | Cardiovascular mortality | All-cause hospitalization | Heart failure hospitalization | |||||||||

| No of studies | Number of patients | Effect | No of studies | Number of patients | Effect | No of studies | Number of patients | Effect | No of studies | Number of patients | Effect | |

| Follow up ≤ 6 mo | 15 | 6781 | Reduced | 3 | 773 | Reduced | 19 | 7442 | No effect | 8 | 2774 | No effect |

| Follow up ≥ 12 mo | 12 | 6159 | Reduced | 5 | 3022 | Reduced | 13 | 5360 | Reduced | 6 | 2962 | Reduced |

| Recent hospitalization | 12 | 5865 | Reduced | 3 | 607 | Reduced | 13 | 6057 | Reduced | 6 | 2486 | No effect |

| No recent hospitalization | 16 | 7417 | Reduced | 6 | 3436 | Reduced | 20 | 6993 | Reduced | 8 | 3250 | Reduced |

| Patients ≥ 65 yr | 7 | 1522 | Reduced | - | - | - | 8 | 1611 | No effect | - | - | - |

Furthermore, our sensitivity analysis showed that being recently hospitalized for heart failure, which we defined as heart failure hospitalization within six weeks before the study, did not affect the telemonitoring outcome. The analysis of 12 studies that recruited patients recently hospitalized for heart failure showed reduced all-cause mortality in telemonitoring patients (RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.71-0.97, P = 0.021). Similarly, an analysis of 16 studies that recruited patients who were not recently hospitalized showed reduced all-cause mortality in telemonitoring patients (RR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.69-0.95, P = 0.01) (Table 3). Analysis of seven studies that recruited only patients 65 years or more showed that telemonitoring reduced all-cause mortality in this age group (RR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.50-0.87, P = 0.004).

The pooled estimate of the effect of telemonitoring on cardiovascular death in comparison with standard care in nine studies with 4043 patients showed that telemonitoring was associated with reduced cardiovascular mortality in heart failure patients (RR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.54-0.81, P < 0.001) (Figure 2B). Two studies were excluded from the analysis because they reported no cardiovascular deaths in the telemonitoring and usual care groups.

Our sensitivity analysis showed that the duration of telemonitoring did not influence cardiovascular mortality in heart failure patients. Analysis of 3 studies of 6 mo or less duration showed reduced cardiovascular mortality in telemonitoring patients (RR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.28-0.79, P = 0.005). Similarly, our analysis of 5 studies of 12 mo or more duration showed reduced cardiovascular mortality in telemonitoring patients (RR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.56-0.90, P = 0.005) (Table 3).

Furthermore, our sensitivity analysis showed that being recently hospitalized for heart failure, which we defined as heart failure hospitalization within six weeks before the study, did not affect the telemonitoring outcome. Analysis of 3 studies that recruited patients with recent hospitalization showed reduced cardiovascular mortality in telemonitoring patients (RR = 0.57, 95%CI: 0.35-0.94, P = 0.026). Similarly, our analysis of 6 studies that recruited patients with no recent hospitalization showed reduced cardiovascular mortality in telemonitoring patients (RR = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.54-0.85, P = 0.001) (Table 3).

The pooled estimate of the effect of telemonitoring on all-cause hospitalization in comparison with standard care in 33 studies with 13050 patients showed that telemonitoring was associated with reduced all-cause hospitalization in heart failure patients (RR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.80-0.94, P = 0.002) (Figure 2C).

Our sensitivity analysis showed that the duration of telemonitoring influenced all-cause hospitalization in heart failure patients. Analysis of 19 studies with six months or less duration showed no effect of telemonitoring on all-cause hospitalization (RR = 0.93, 95%CI: 0.83-1.04, P = 0.21). Conversely, our analysis of 13 studies with 12 mo or more duration showed that telemonitoring reduced all-cause hospitalization (RR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.68-0.92, P = 0.002) (Table 3).

Furthermore, our sensitivity analysis showed that being recently hospitalized for heart failure did not affect the all-cause hospitalization. Analysis of 13 studies that recruited recently hospitalized heart failure patients showed that telemonitoring reduced all-cause hospitalization (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.74-0.98, P = 0.03). Similarly, our analysis of 20 studies that recruited patients that were not recently hospitalized showed that telemonitoring also reduced all-cause hospitalization in this group (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.78-0.98, P = 0.03) (Table 3). Analysis of eight studies that recruited only patients 65 years or older showed that telemonitoring did not affect all-cause hospitalization in this age group (RR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.58-1.02, P = 0.071).

The pooled estimate of the effect of telemonitoring on heart failure hospitalization compared to standard care in 14 studies with 5736 patients showed that telemonitoring had no effect on heart failure hospitalization (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.77-1.01, P = 0.066) (Figure 2D). Our sensitivity analysis showed that the duration of telemonitoring influenced heart failure hospitalization. Analysis of 8 studies of six months or less duration showed no effect of telemonitoring on heart failure hospitalization (RR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.65-1.23, P = 0.50). Conversely, our analysis of 6 studies of 12 mo or more duration showed that telemonitoring reduced heart failure hospitalization (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.75-0.95, P = 0.004) (Table 3).

Sensitivity analysis showed that telemonitoring had no effect on heart failure hospitalization in patients recently discharged from the hospital. Analysis of 6 studies showed no effect on heart failure hospitalization (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.61-1.21, P = 0.37). Conversely, our analysis of 8 studies that recruited patients that were not recently hospitalized showed that telemonitoring reduced heart failure hospitalization (RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.76-0.98, P = 0.02) (Table 3).

Our study demonstrated that home telemonitoring in heart failure patients was associated with reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. These findings are consistent with previous meta-analyses of heart failure patients but inconsistent with some others[6,47-49]. Our sensitivity analysis showed that all-cause and cardiovascular mortality reduction was seen with short (six months or less) and longer (one year or more) telemonitoring. The decrease in mortality was also seen in studies that recruited recently hospitalized heart failure patients, which we defined as heart failure hospitalization within six weeks before the study, and those that did not. The decrease in mortality seen in-home telemonitoring could be due to early detection of clinical deterioration and early intervention.

Our study found that telemonitoring marginally decreased the all-cause hospitalization but did not decrease heart failure-related hospitalization. Some prior meta-analysis did not show reduced all-cause hospitalization[49-52] or heart failure-related hospitalization[52] with telemonitoring in heart failure patients. It is reasonable to expect that telemonitoring and early intervention will reduce hospitalization by detecting clinical deterioration early and early intervention. Conversely, telemonitoring could lead to more frequent hospitalization. This is because telemonitoring patients have more frequent contact with the healthcare system, and severe episodes of decompensation requiring hospitalization will be detected early. In this case, it will be expected that such patients will come to the hospital at the early stage of severe decompensation and that duration of hospitalization will be shorter. Unfortunately, length of hospital stay was inconsistently reported in the studies, preventing meta-analysis of telemonitoring on this outcome. However, our sensitivity analysis showed that while short-duration telemonitoring (6 mo or less) did not affect both all-cause hospitalization and heart failure hospitalization, long-duration telemonitoring (12 mo or more) showed a reduction in both all-cause and heart failure hospitalization. This may explain why some earlier meta-analyses with fewer studies showed a decrease in heart failure hospitalization with telemonitoring[49,53]. In the long run, telemonitoring may lead to early detection of clinical deterioration and early interventions that reduce hospitalization.

Some studies included scheduled nurse-led patient interaction or education as part of the intervention in addition to measuring and transmitting vital signs. The scheduled patient-nurse interactions included counseling if there is an acute change in health status, providing patient self-care education, adjusting medications using designated protocols, monitoring disease signs and symptoms, monitoring medication adherence, and addressing technical and social issues[10,13,14]. Three studies had the scheduled patient-nurse education and interaction in both the control and telemonitoring groups, while seven had the education and interaction in only the telemonitoring group. Thus, we thought that the additional intervention might partially explain the decrease in all-cause mortality with telemonitoring in those studies. However, our sensitivity analysis in the seven studies that received further intervention showed that telemonitoring with additional patient education did not affect heart failure hospitalization or mortality. This points that telemonitoring and not the additional interventions were likely responsible for the improved mortality seen in these studies.

Additionally, we had thought that home telemonitoring might be more helpful in reducing hospitalization and death in recently hospitalized or newly diagnosed heart failure patients who need support and education. However, our sensitivity analysis showed that home telemonitoring reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in both studies that recruited patients recently hospitalized for heart failure and those that did not. Similarly, telemonitoring reduced all-cause hospitalization in both studies that recruited patients who were recently hospitalized for heart failure and those who had not. However, contrary to our expectation, home telemonitoring did not affect heart failure hospitalization in studies that recruited patients recently hospitalized for heart failure. However, this might reflect the small number of trials and participants rather than an actual lack of effect.

There are certain limitations to this study. First, home telemonitoring organizations sponsored some of the studies included in this review. This may have introduced a conflict of interest and bias in the results that were published. Secondly, many of the studies had incomplete reporting of their study methodology, making it difficult to classify them as high or low bias studies. Thus, the risk of bias in some of the studies was unclear. Thirdly, some of the sensitivity analyses involved a combination of a few small-sized studies. The small number of studies and participants may make it difficult to detect an effect, even if one exists.

Prolonged home telemonitoring (12 mo or more) was associated with both decreased all-cause and heart failure hospitalization, unlike shorter duration (6 mo or less) telemonitoring. The implication for practice is that hospitals considering telemonitoring to reduce heart failure readmission rates may need to plan for prolonged telemonitoring to see the effect they are looking for. In addition, these hospitals or organizations will need to consider the cost of prolonged telemonitoring viz-a-viz the cost of rehospitalization. The opportunities for future research include a cost-benefit analysis of home telemonitoring in heart failure patients. There is also a need for more studies on the effect of telemonitoring on frequently hospitalized heart failure patients.

The results of this meta-analysis support the benefit of home telemonitoring using digital/broadband/ satellite/wireless or blue-tooth transmission of physiological data in reducing all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in heart failure patients. In addition, this analysis also shows the benefit of prolonged telemonitoring (≥ 12 mo) in reducing all-cause and heart failure-related hospitalization.

Home telemonitoring has been used as a modality to prevent readmission and improve outcomes for patients with heart failure.

However, while telemonitoring was beneficial in reducing hospital admission, all-cause mortality, and emergency room visits in some studies, others did not show such benefits. These differences in outcomes from multiple studies suggest that a careful analysis of study outcomes is needed to determine its aggregate benefit to heart failure patients.

This meta-analysis aims to determine the aggregate effect of telemonitoring on all-cause mortality, heart failure-related mortality, all-cause hospitalization, and heart failure-related hospitalization in heart failure patients.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 home telemonitoring randomized controlled trials involving 14993 patients.

Home telemonitoring in heart failure patients was associated with reduced cardiovascular [relative risk (RR) = 0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.54-0.81, P < 0.001] and all-cause mortality (RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.75-0.92, P = 0.001). Furthermore, telemonitoring was associated with decreased all-cause hospitalization (RR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.80-0.94, P = 0.002) but not heart failure-related hospitalization (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.77-1.01, P = 0.066). Interestingly, prolonged home telemonitoring (12 mo or more) was associated with both decreased all-cause and heart failure hospitalization, unlike shorter duration (6 mo or less) telemonitoring.

Home telemonitoring reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in heart failure patients. This study found that prolonged home telemonitoring (12 mo or more) led to both decreased all-cause and heart failure hospitalization, unlike shorter duration (6 mo or less) telemonitoring. The implication for practice is that hospitals considering telemonitoring to reduce heart failure readmission rates may need to plan for prolonged telemonitoring to see the effect they are looking for.

The opportunities for future research include a cost-benefit analysis of home telemonitoring in heart failure patients. There is also a need for more studies on the effect of telemonitoring on frequently hospitalized heart failure patients.

We will like to thank Dr. Hycienth Ahaneku for reviewing the data analysis and methods section.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lakusic N, Croatia; Su Q, China; Yang YQ, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Bozkurt B, Coats A, Tsutsui H. A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure Consensus Conference. European J Heart Fail. 2021;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 832] [Article Influence: 208.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Writing Committee Members; Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 795] [Cited by in RCA: 1565] [Article Influence: 130.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kolte D, Abbott JD, Aronow HD. Interventional Therapies for Heart Failure in Older Adults. Heart Fail Clin. 2017;13:535-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6-e245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2893] [Cited by in RCA: 3392] [Article Influence: 282.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3684] [Cited by in RCA: 3911] [Article Influence: 244.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Inglis SC, Clark RA, Dierckx R, Prieto-Merino D, Cleland JG. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD007228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koehler F, Winkler S, Schieber M, Sechtem U, Stangl K, Böhm M, Boll H, Baumann G, Honold M, Koehler K, Gelbrich G, Kirwan BA, Anker SD; Telemedical Interventional Monitoring in Heart Failure Investigators. Impact of remote telemedical management on mortality and hospitalizations in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure: the telemedical interventional monitoring in heart failure study. Circulation. 2011;123:1873-1880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 505] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kotooka N, Kitakaze M, Nagashima K, Asaka M, Kinugasa Y, Nochioka K, Mizuno A, Nagatomo D, Mine D, Yamada Y, Kuratomi A, Okada N, Fujimatsu D, Kuwahata S, Toyoda S, Hirotani SI, Komori T, Eguchi K, Kario K, Inomata T, Sugi K, Yamamoto K, Tsutsui H, Masuyama T, Shimokawa H, Momomura SI, Seino Y, Sato Y, Inoue T, Node K; HOMES-HF study investigators. The first multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of home telemonitoring for Japanese patients with heart failure: home telemonitoring study for patients with heart failure (HOMES-HF). Heart Vessels. 2018;33:866-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pekmezaris R, Nouryan CN, Schwartz R, Castillo S, Makaryus AN, Ahern D, Akerman MB, Lesser ML, Bauer L, Murray L, Pecinka K, Zeltser R, Zhang M, DiMarzio P. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Telehealth Self-Management to Standard Outpatient Management in Underserved Black and Hispanic Patients Living with Heart Failure. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25:917-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kalter-Leibovici O, Freimark D, Freedman LS, Kaufman G, Ziv A, Murad H, Benderly M, Silverman BG, Friedman N, Cukierman-Yaffe T, Asher E, Grupper A, Goldman D, Amitai M, Matetzky S, Shani M, Silber H; Israel Heart Failure Disease Management Study (IHF-DMS) investigators. Disease management in the treatment of patients with chronic heart failure who have universal access to health care: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2017;15:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 39703] [Article Influence: 9925.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2019. |

| 13. | Koehler F, Koehler K, Deckwart O, Prescher S, Wegscheider K, Kirwan BA, Winkler S, Vettorazzi E, Bruch L, Oeff M, Zugck C, Doerr G, Naegele H, Störk S, Butter C, Sechtem U, Angermann C, Gola G, Prondzinsky R, Edelmann F, Spethmann S, Schellong SM, Schulze PC, Bauersachs J, Wellge B, Schoebel C, Tajsic M, Dreger H, Anker SD, Stangl K. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1047-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 64.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cleland JG, Louis AA, Rigby AS, Janssens U, Balk AH; TEN-HMS Investigators. Noninvasive home telemonitoring for patients with heart failure at high risk of recurrent admission and death: the Trans-European Network-Home-Care Management System (TEN-HMS) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1654-1664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nouryan CN, Morahan S, Pecinka K, Akerman M, Lesser M, Chaikin D, Castillo S, Zhang M, Pekmezaris R. Home Telemonitoring of Community-Dwelling Heart Failure Patients After Home Care Discharge. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25:447-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Seto E, Leonard KJ, Cafazzo JA, Barnsley J, Masino C, Ross HJ. Mobile phone-based telemonitoring for heart failure management: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Weintraub A, Gregory D, Patel AR, Levine D, Venesy D, Perry K, Delano C, Konstam MA. A multicenter randomized controlled evaluation of automated home monitoring and telephonic disease management in patients recently hospitalized for congestive heart failure: the SPAN-CHF II trial. J Card Fail. 2010;16:285-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Blum K, Gottlieb SS. The effect of a randomized trial of home telemonitoring on medical costs, 30-day readmissions, mortality, and health-related quality of life in a cohort of community-dwelling heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2014;20:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dansky KH, Vasey J, Bowles K. Impact of telehealth on clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. Clin Nurs Res. 2008;17:182-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kashem A, Droogan MT, Santamore WP, Wald JW, Bove AA. Managing heart failure care using an internet-based telemedicine system. J Card Fail. 2008;14:121-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Benatar D, Bondmass M, Ghitelman J, Avitall B. Outcomes of chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:347-352. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pedone C, Rossi FF, Cecere A, Costanzo L, Antonelli Incalzi R. Efficacy of a Physician-Led Multiparametric Telemonitoring System in Very Old Adults with Heart Failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1175-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wade MJ, Desai AS, Spettell CM, Snyder AD, McGowan-Stackewicz V, Kummer PJ, Maccoy MC, Krakauer RS. Telemonitoring with case management for seniors with heart failure. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:e71-e79. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Comín-Colet J, Enjuanes C, Verdú-Rotellar JM, Linas A, Ruiz-Rodriguez P, González-Robledo G, Farré N, Moliner-Borja P, Ruiz-Bustillo S, Bruguera J. Impact on clinical events and healthcare costs of adding telemedicine to multidisciplinary disease management programmes for heart failure: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22:282-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Olivari Z, Giacomelli S, Gubian L, Mancin S, Visentin E, Di Francesco V, Iliceto S, Penzo M, Zanocco A, Marcon C, Anselmi M, Marchese D, Stafylas P. The effectiveness of remote monitoring of elderly patients after hospitalisation for heart failure: The renewing health European project. Int J Cardiol. 2018;137-142:CD007228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lyngå P, Persson H, Hägg-Martinell A, Hägglund E, Hagerman I, Langius-Eklöf A, Rosenqvist M. Weight monitoring in patients with severe heart failure (WISH). A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:438-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Scherr D, Kastner P, Kollmann A, Hallas A, Auer J, Krappinger H, Schuchlenz H, Stark G, Grander W, Jakl G, Schreier G, Fruhwald FM; MOBITEL Investigators. Effect of home-based telemonitoring using mobile phone technology on the outcome of heart failure patients after an episode of acute decompensation: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Antonicelli R, Testarmata P, Spazzafumo L, Gagliardi C, Bilo G, Valentini M, Olivieri F, Parati G. Impact of telemonitoring at home on the management of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:300-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Giordano A, Scalvini S, Zanelli E, Corrà U, Longobardi GL, Ricci VA, Baiardi P, Glisenti F. Multicenter randomised trial on home-based telemanagement to prevent hospital readmission of patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2009;131:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ong MK, Romano PS, Edgington S, Aronow HU, Auerbach AD, Black JT, De Marco T, Escarce JJ, Evangelista LS, Hanna B, Ganiats TG, Greenberg BH, Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Kimchi A, Liu H, Lombardo D, Mangione CM, Sadeghi B, Sarrafzadeh M, Tong K, Fonarow GC; Better Effectiveness After Transition–Heart Failure (BEAT-HF) Research Group. Effectiveness of Remote Patient Monitoring After Discharge of Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure: The Better Effectiveness After Transition -- Heart Failure (BEAT-HF) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:310-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mortara A, Pinna GD, Johnson P, Maestri R, Capomolla S, La Rovere MT, Ponikowski P, Tavazzi L, Sleight P; HHH Investigators. Home telemonitoring in heart failure patients: the HHH study (Home or Hospital in Heart Failure). Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:312-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dar O, Riley J, Chapman C, Dubrey SW, Morris S, Rosen SD, Roughton M, Cowie MR. A randomized trial of home telemonitoring in a typical elderly heart failure population in North West London: results of the Home-HF study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:319-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Vuorinen AL, Leppänen J, Kaijanranta H, Kulju M, Heliö T, van Gils M, Lähteenmäki J. Use of home telemonitoring to support multidisciplinary care of heart failure patients in Finland: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Goldberg LR, Piette JD, Walsh MN, Frank TA, Jaski BE, Smith AL, Rodriguez R, Mancini DM, Hopton LA, Orav EJ, Loh E; WHARF Investigators. Randomized trial of a daily electronic home monitoring system in patients with advanced heart failure: the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure (WHARF) trial. Am Heart J. 2003;146:705-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Soran OZ, Piña IL, Lamas GA, Kelsey SF, Selzer F, Pilotte J, Lave JR, Feldman AM. A randomized clinical trial of the clinical effects of enhanced heart failure monitoring using a computer-based telephonic monitoring system in older minorities and women. J Card Fail. 2008;14:711-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chaudhry SI, Mattera JA, Curtis JP, Spertus JA, Herrin J, Lin Z, Phillips CO, Hodshon BV, Cooper LS, Krumholz HM. Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2301-2309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 989] [Cited by in RCA: 870] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Villani A, Malfatto G, Compare A, Della Rosa F, Bellardita L, Branzi G, Molinari E, Parati G. Clinical and psychological telemonitoring and telecare of high risk heart failure patients. J Telemed Telecare. 2014;20:468-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Dendale P, De Keulenaer G, Troisfontaines P, Weytjens C, Mullens W, Elegeert I, Ector B, Houbrechts M, Willekens K, Hansen D. Effect of a telemonitoring-facilitated collaboration between general practitioner and heart failure clinic on mortality and rehospitalization rates in severe heart failure: the TEMA-HF 1 (TElemonitoring in the MAnagement of Heart Failure) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:333-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Woodend AK, Sherrard H, Fraser M, Stuewe L, Cheung T, Struthers C. Telehome monitoring in patients with cardiac disease who are at high risk of readmission. Heart Lung. 2008;37:36-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Galinier M, Roubille F, Berdague P, Brierre G, Cantie P, Dary P, Ferradou JM, Fondard O, Labarre JP, Mansourati J, Picard F, Ricci JE, Salvat M, Tartière L, Ruidavets JB, Bongard V, Delval C, Lancman G, Pasche H, Ramirez-Gil JF, Pathak A; OSICAT Investigators. Telemonitoring versus standard care in heart failure: a randomised multicentre trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:985-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Capomolla S, Pinna G, La Rovere MT, Maestri R, Ceresa M, Ferrari M, Febo O, Caporotondi A, Guazzotti G, Lenta F, Baldin S, Mortara A, Cobelli F. Heart failure case disease management program: a pilot study of home telemonitoring vs usual care. European Heart J Suppl. 2004;6:F91-F98. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kulshreshtha A, Kvedar JC, Goyal A, Halpern EF, Watson AJ. Use of remote monitoring to improve outcomes in patients with heart failure: a pilot trial. Int J Telemed Appl. 2010;2010:870959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kenealy TW, Parsons MJ, Rouse AP, Doughty RN, Sheridan NF, Hindmarsh JK, Masson SC, Rea HH. Telecare for diabetes, CHF or COPD: effect on quality of life, hospital use and costs. A randomised controlled trial and qualitative evaluation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dawson NL, Hull BP, Vijapura P, Dumitrascu AG, Ball CT, Thiemann KM, Maniaci MJ, Burton MC. Home Telemonitoring to Reduce Readmission of High-Risk Patients: a Modified Intention-to-Treat Randomized Clinical Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:3395-3401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Delaney C, Apostolidis B, Bartos S, Morrison H, Smith L, Fortinsky R. A randomized trial of telemonitoring and self-care education in heart failure patients following home care discharge. Home Health Care Management & Practice. 2013;25:187-195. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Schwarz KA, Mion LC, Hudock D, Litman G. Telemonitoring of heart failure patients and their caregivers: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:18-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yun JE, Park JE, Park HY, Lee HY, Park DA. Comparative Effectiveness of Telemonitoring Versus Usual Care for Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Card Fail. 2018;24:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Polisena J, Tran K, Cimon K, Hutton B, McGill S, Palmer K, Scott RE. Home telemonitoring for congestive heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Clarke M, Shah A, Sharma U. Systematic review of studies on telemonitoring of patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | McAlister FA, Stewart S, Ferrua S, McMurray JJ. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:810-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Clark RA, Inglis SC, McAlister FA, Cleland JG, Stewart S. Telemonitoring or structured telephone support programmes for patients with chronic heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334:942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Pekmezaris R, Tortez L, Williams M, Patel V, Makaryus A, Zeltser R, Sinvani L, Wolf-Klein G, Lester J, Sison C, Lesser M, Kozikowski A. Home Telemonitoring In Heart Failure: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:1983-1989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Inglis SC, Clark RA, McAlister FA, Stewart S, Cleland JG. Which components of heart failure programmes are effective? Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1028-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |