Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v12.i11.526

Peer-review started: June 24, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: July 28, 2020

Accepted: October 5, 2020

Article in press: October 5, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 154 Days and 16.2 Hours

Vascular endothelial dysfunction is an underlying pathophysiological feature of chronic heart failure (CHF). Patients with CHF are characterized by impaired vasodilation and inflammation of the vascular endothelium. They also have low levels of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). EPCs are bone marrow derived cells involved in endothelium regeneration, homeostasis, and neovascularization. Exercise has been shown to improve vasodilation and stimulate the mobilization of EPCs in healthy people and patients with cardiovascular comorbidities. However, the effects of exercise on EPCs in different stages of CHF remain under investigation.

To evaluate the effect of a symptom-limited maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) on EPCs in CHF patients of different severity.

Forty-nine consecutive patients (41 males) with stable CHF [mean age (years): 56 ± 10, ejection fraction (EF, %): 32 ± 8, peak oxygen uptake (VO2, mL/kg/min): 18.1 ± 4.4] underwent a CPET on a cycle ergometer. Venous blood was sampled before and after CPET. Five circulating endothelial populations were quantified by flow cytometry: Three subgroups of EPCs [CD34+/CD45-/CD133+, CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 and CD34+/CD133+/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)] and two subgroups of circulating endothelial cells (CD34+/CD45-/CD133- and CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2). Patients were divided in two groups of severity according to the median value of peak VO2 (18.0 mL/kg/min), predicted peak VO2 (65.5%), ventilation/carbon dioxide output slope (32.5) and EF (reduced and mid-ranged EF). EPCs values are expressed as median (25th-75th percentiles) in cells/106 enucleated cells.

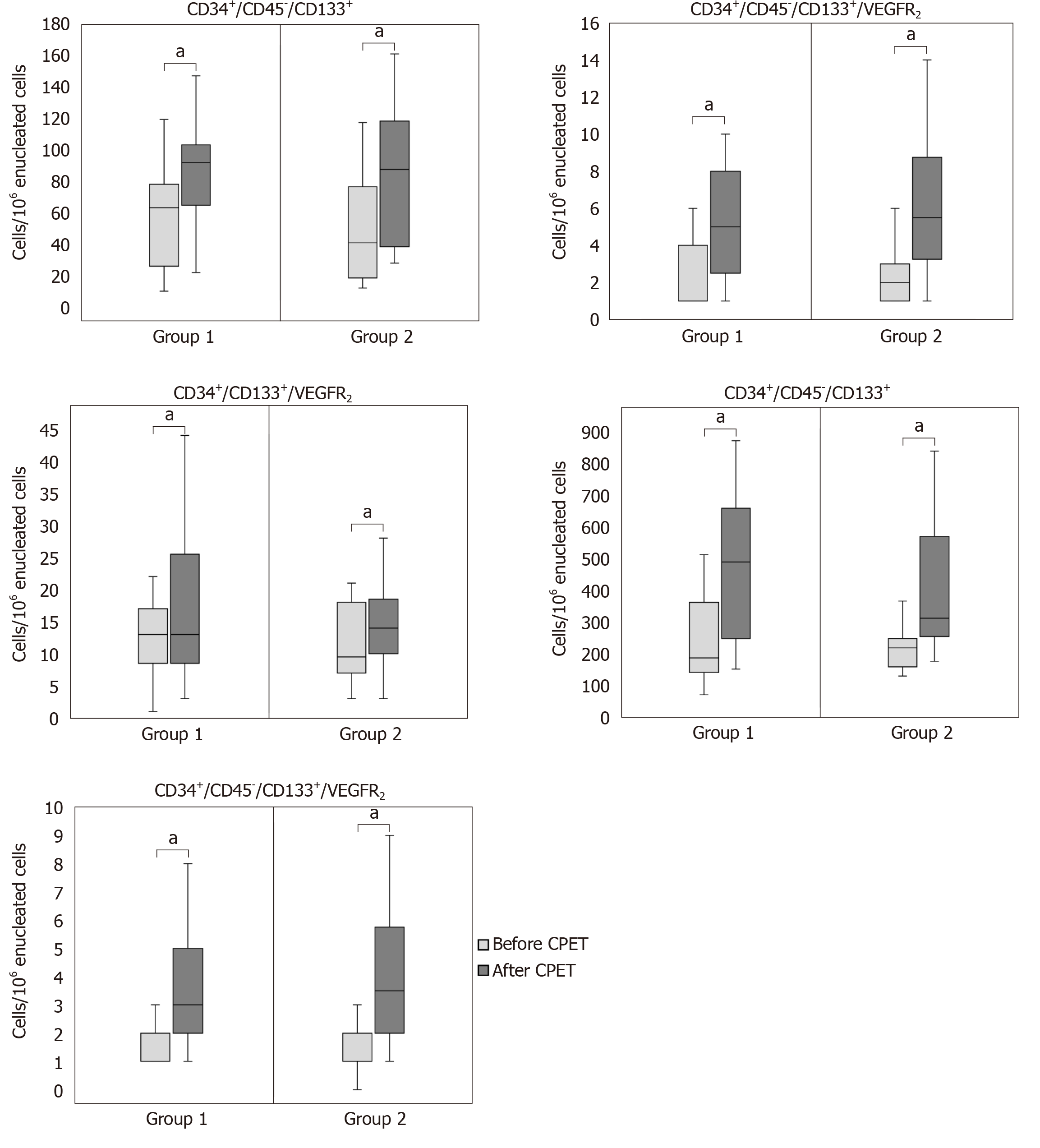

Patients with lower peak VO2 increased the mobilization of CD34+/CD45-/CD133+ [pre CPET: 60 (25-76) vs post CPET: 90 (70-103) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001], CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 [pre CPET: 1 (1-4) vs post CPET: 5 (3-8) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001], CD34+/CD45-/CD133- [pre CPET: 186 (141-361) vs post CPET: 488 (247-658) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001] and CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 [pre CPET: 2 (1-2) vs post CPET: 3 (2-5) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001], while patients with higher VO2 increased the mobilization of CD34+/CD45-/CD133+ [pre CPET: 42 (19-73) vs post CPET: 90 (39-118) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001], CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 [pre CPET: 2 (1-3) vs post CPET: 6 (3-9) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001], CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 [pre CPET: 10 (7-18) vs post CPET: 14 (10-19) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.01], CD34+/CD45-/CD133- [pre CPET: 218 (158-247) vs post CPET: 311 (254-569) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001] and CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 [pre CPET: 1 (1-2) vs post CPET: 4 (2-6) cells/106 enucleated cells, P < 0.001]. A similar increase in the mobilization of at least four out of five cellular populations was observed after maximal exercise within each severity group regarding predicted peak, ventilation/carbon dioxide output slope and EF as well (P < 0.05). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the mobilization of endothelial cellular populations between severity groups in each comparison (P > 0.05).

Our study has shown an increased EPCs and circulating endothelial cells mobilization after maximal exercise in CHF patients, but this increase was not associated with syndrome severity. Further investigation, however, is needed.

Core Tip: Vascular endothelial dysfunction is an underlying pathophysiological feature of chronic heart failure (CHF). Exercise has been proven to increase the mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), which are involved in vascular endothelial restoration and neo-vascularization, in healthy people and patients with co-morbidities. However, the effect of exercise on EPCs in patients with CHF of different severity remains unknown. In the present study, we compared the mobilization of EPCs in CHF patients of different severity, according to functional markers, after a symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise testing. No differences were found between severity groups, indicating thus the beneficial effect of exercise in these patients.

- Citation: Kourek C, Karatzanos E, Psarra K, Georgiopoulos G, Delis D, Linardatou V, Gavrielatos G, Papadopoulos C, Nanas S, Dimopoulos S. Endothelial progenitor cells mobilization after maximal exercise according to heart failure severity. World J Cardiol 2020; 12(11): 526-539

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v12/i11/526.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v12.i11.526

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a multifactorial clinical syndrome with an incidence between 1% and 2% per year in developed countries in all age categories, while increasing to > 10% in the age category > 70 years[1]. Prognosis of patients with CHF is poor as the survival rates do not exceed 50% within 4 years and 26.7% within 10 years from the diagnosis[2,3].

A characteristic pathophysiological feature of CHF is vascular endothelial dysfunction[4] and microcirculation abnormalities associated with CHF severity[5]. Systemic inflammation caused by secretion of cytokines leads to disruption of the vascular endothelial barrier and causes acute endothelitis[6]. Vessels show impaired vasodilation due to increased degradation and reduced bioavailability of the nitric oxide (NO)[6,7].

Exercise has a beneficial impact in the function of the vascular endothelium. It has been shown that it suppresses the generation of free radicals and oxidative stress, increases the bioavailability of NO and induces vasodilation, thereby improving the aerobic capacity[8,9]. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have been proven to be involved in the shielding of vascular protection, the restoring of dysfunctional and injured endothelium, the promotion of angiogenesis and the regulation of vascular homeostasis[10,11]. The level of EPCs seem to predict the occurrence of cardiovascular events and death from cardiovascular causes and may help to identify patients at increased cardiovascular risk[12]. Low counts of EPCs have been shown to be strongly and independently predictive of mortality in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities[13].

Regular aerobic exercise induces the mobilization of EPCs from the bone marrow, not only in the healthy population but also in populations with comorbidities and increased risk factors[14,15]. However, the effect of maximal exercise on EPCs in patients with CHF, and especially in patients of different severity, remains under investigation.

We hypothesized that maximal exercise has a beneficial effect on vascular endothelial function in patients with CHF irrespectively of their severity. The aim of the study was to assess, quantify and compare the acute mobilization of EPCs after maximal exercise in patients with CHF of both lower and higher severity.

This interventional clinical study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Administration Board and the Ethics Committee of “Evaggelismos General Hospital” in Athens, Greece (Approval No. 117/3-7-2017). All of the patients signed an informed consent form in order to participate in the study. This is a post-hoc analysis study of a previous conducted research study published recently aiming to assess EPCs mobilization after exercise in patients with CHF[16]. Patients were referred for assessment to the “Clinical Ergospirometry, Exercise and Rehabilitation Laboratory” of “Evaggelismos General Hospital” by heart failure outpatient clinics of Athens. The diagnosis of CHF was based on personal history forms, clinical evaluation and laboratory testing of every patient.

The population of the study consisted of 49 consecutive patients with stable CHF and a reduced or mid-ranged ejection fraction (EF) who underwent a single session of symptom limited maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (Ergoline 800; SensorMedics Corporation, Anaheim, CA, United States). Inclusion criteria were stable CHF at maximum tolerated medication and EF ≤ 49%. Exclusion criteria were severe valvulopathy, uncontrolled arterial hypertension, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, severe peripheral angiopathy, neuromuscular diseases and contraindications for maximum cardiopulmonary stress testing[17].

Patients were divided in groups according to syndrome severity. CPET indices [peak oxygen uptake (VO2), predicted peak VO2 and ventilation (VE)/carbon dioxide output (VCO2)] were used in order to divide these patients in two groups for each parameter. Cut off values (medians) were set for each of these parameters; a value of 18.0 mL/kg/min was set for peak VO2, a value of 65.5% for predicted peak VO2 and a value of 32.5 for VE/VCO2. The demographic and exercise characteristics between severity groups divided by peak VO2 are shown in Table 1 and for the other parameters in Supplementary Tables 1-3).

| Demographic characteristics | Group 1 | Group 2 |

| Patients, n | 25 | 24 |

| Gender, males/females | 21/4 | 20/4 |

| Age in yr1 | 57 ± 10 | 55 ± 9 |

| Height in cm1 | 174 ± 11 | 175 ± 9 |

| Weight in kg1 | 92 ± 25 | 87 ± 21 |

| NYHA stage, class II/III | 16/9 | 18/6 |

| EF, %1 | 32 ± 9 | 32 ± 8 |

| Type of CHF | ||

| Dilated cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 7 (28) | 5 (21) |

| Ischemic, n (%) | 14 (56) | 15 (63) |

| Other, i.e. valvulopathy, etc., n (%) | 4 (16) | 4 (17) |

| Medication | ||

| Diuretics, n (%) | 19 (76) | 13 (54) |

| ACE inhibitors, n (%) | 11 (44) | 13 (54) |

| ARBs, n (%) | 5 (20) | 2 (8) |

| β-Blockers, n (%) | 25 (100) | 23 (96) |

| Aldosterone antagonists, n (%) | 19 (76) | 18 (75) |

| Cardiopulmonary exercise testing parameters | ||

| Peak VO2 in mL/kg/min1 | 14.5 ± 2.5 | 21.8 ± 2.4a |

| Predicted peak VO2, %1 | 52 ± 13 | 74 ± 11a |

| VE/VCO2 slope1 | 34 ± 5 | 33 ± 4 |

| Peak WR in watts1 | 75 ± 34 | 118 ± 34a |

| Endothelial cellular populations | Group 1 of n = 25, peak VO2 < 18.0 mL/kg/min | Group 2 of n = 24, peak VO2 ≥ 18.0 mL/kg/min | P value between groups | ||

| Before CPET | After CPET | Before CPET | After CPET | ||

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133+ | 60 (25-76) | 90 (70-103)e | 42 (19-73) | 90 (39-118)e | 0.329 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 | 1 (1-4) | 5 (3-8)e | 2 (1-3) | 6 (3-9)e | 0.075 |

| CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 | 13 (9-17) | 13 (9-26) | 10 (7-18) | 14 (10-19)b | 0.257 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133- | 186 (141-361) | 488 (247-658)e | 218 (158-247) | 311 (254-569)e | 0.101 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 | 2 (1-2) | 3 (2-5)e | 1 (1-2) | 4 (2-6)e | 0.471 |

Patients were also divided in two groups according to their EF. The first group consisted of patients with CHF with a reduced EF (< 40%), while the second group included patients with CHF with a mid-ranged EF (40%-49%).

Patient performed a ramp-incremental exercise test, using the Hansen et al[18] equation for individual work rate increments, so as to aim for a test of 8-12 min duration. The nose of the patients was clamped, and they breathed through a special mask with a low resistance valve and a known gas mixture. Breathing parameters such as VO2, VCO2 and VE were measured in each breath by the software, and their values were recorded at the monitor of the computer system (Vmax 229, Sensor Medics). The gas exchanges of each patient were also recorded in order to calculate more specific values such as resting VO2, VO2 at peak exercise (peak VO2), predicted VO2 at peak exercise (predicted peak VO2) and VE/VCO2 slope.

All of the measurements were usually recorded in four time points; the first was for 2 min at rest (baseline values), the second for 2 min of unloaded pedaling before the beginning of the exercise, the third during exercise and the last for 5 min during the recovery point. A 12-lead electrocardiogram system was also attached on the patient’s body in order to monitor the heart rate and the heart rhythm, a pulse oxymeter on the patient’s finger measured the saturation and blood pressure was measured very 2 min. The end point of the session was due to electrocardiogram abnormal rhythm at the monitor, dyspnea or leg fatigue of the patient.

The peak values for VO2, VCO2 and VE were calculated as the average of measurements made during the 20-s period before the end of exercise[19]. Peak work rate was defined as the highest work rate reached and maintained at a pedaling frequency of no less than 65 revolutions per min. The ventilatory response to exercise was calculated as the slope by linear regression of VE vs VCO2 from the beginning of exercise to anaerobic threshold, where the relationship was linear[19].

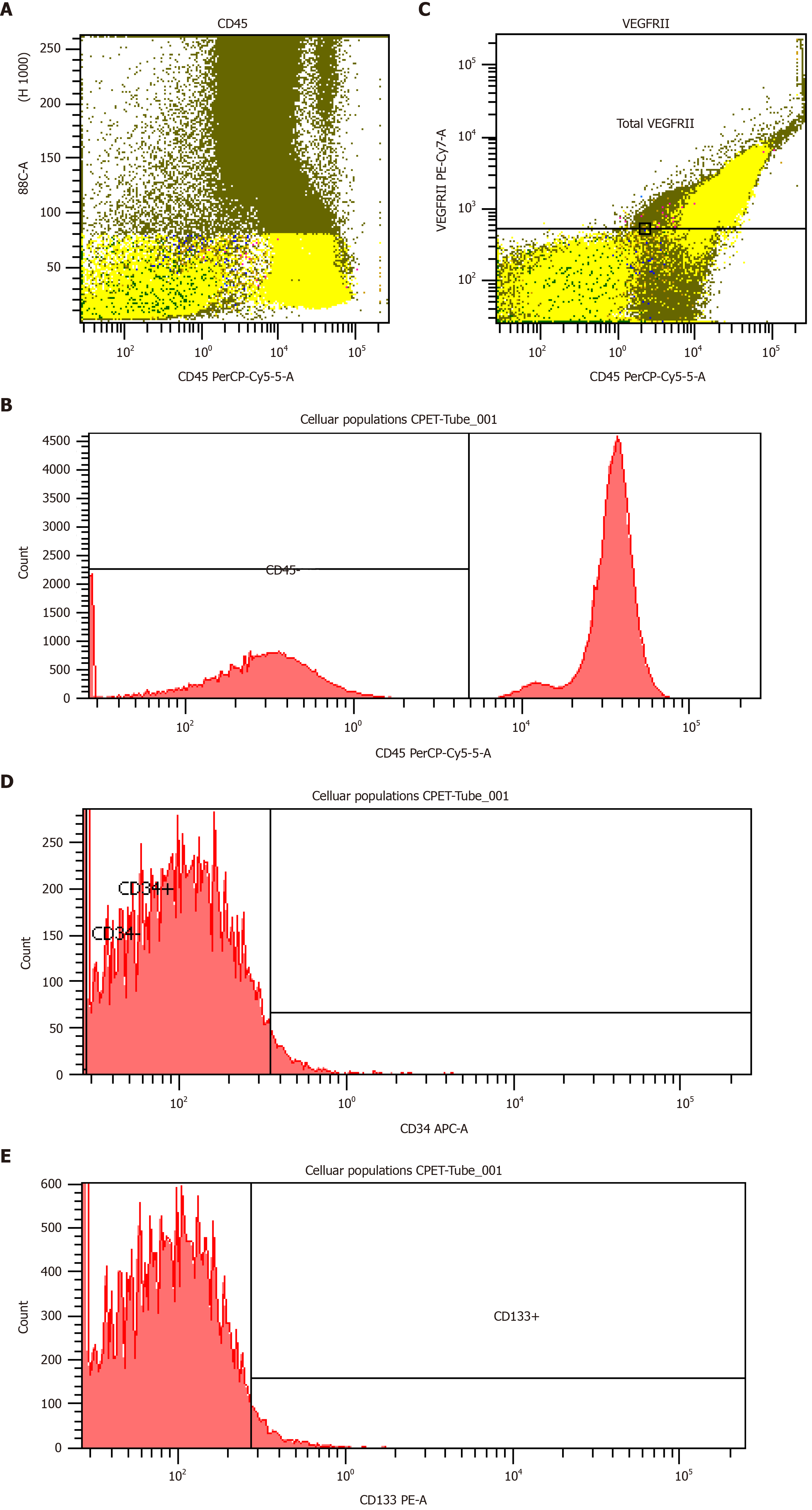

For evaluation of EPCs, blood samples were drawn from a peripheral vein of each patient, once before the CPET at rest and once just after the CPET. Venous blood was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes. Blood samples were taken to the immunology laboratory within the first hour after the collection where they were measured with the use of flow cytometry. The protocol that we implemented was the Duda et al[20] protocol, where four types of monoclonal antibodies were used; CD45, CD34, CD133 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2, CD309). In the meantime, five different cellular populations, three subgroups of EPCs and two subgroups of circulating endothelial cells (CECs) were defined; these were CD34+/CD45-/CD133+, CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2, CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 (EPCs subgroups), CD34+/CD45-/CD133- and CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 (CECs subgroups).

Four-color flow cytometry was performed in the Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory with BD FACSCantoII (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) flow cytometer. Each analysis on the flow cytometer included 1 × 106 events. The number of EPCs was expressed as absolute number of cells/106 enucleated cells (Figure 1).

Patients were divided according to CHF severity based on CPET assessment, and results are presented according to severity groups. Descriptive characteristics are expressed as mean ± standard deviation while values of cellular populations belong to non-normal distribution, and they are expressed in median (25th-75th percentiles). All categorical variables are presented as absolute and percentage values. Normality of distribution was checked with the Shapiro-Wilk test. We used the Spearman’s correlation coefficient to assess the direction and the magnitude of the association between the absolute and percentage differences of each endothelial cellular population and the values of CPET parameters and EF. Unpaired two sample Student’s t test analyzed differences in demographics and CPET parameters between severity groups. Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-parametric data analyzed differences between cellular populations within severity groups. Differences between severity groups were assessed with factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) 2 × 2 (time × group). Dependent variables were transformed with the natural logarithm when deviating from normality prior to entering the ANOVA models. All tests were two-tailed, and level of observed statistical significance was adjusted to 0.05. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed as ANOVA analyses assessed independent outcomes. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 25 Statistics software (Armonk, NY, United States).

Both severity groups, which were divided according to the median value of peak VO2, increased the mobilization of their endothelial cellular populations after a symptom-limited CPET (Table 2). In group 1 (peak VO2 < 18.0 mL/kg/min), all endothelial cellular populations increased except for the CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 EPCs population, while in group 2 (peak VO2 ≥ 18.0 mL/kg/min) all endothelial cellular populations increased (Table 2). No differences in the mobilization of endothelial cellular populations between the two severity groups were observed (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the difference between the two groups.

Regarding severity groups divided according to the median value of predicted peak VO2, they both increased the mobilization of their endothelial cellular populations after maximal CPET (Supplementary Table 4). In group 1 (predicted peak VO2 < 65.5%), all endothelial cellular populations increased, while in group 2 (predicted peak VO2 ≥ 65.5%) all endothelial cellular populations increased except for the CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 EPCs population (Supplementary Table 4). No differences in the mobilization of endothelial cellular populations between the two severity groups were observed (Supplementary Table 4).

As far as severity groups divided according to the median value of VE/VCO2 slope are concerned, they both increased the mobilization of their endothelial cellular populations after maximal CPET (Table 3). In group 1 (VE/VCO2 < 32.5), all endothelial cellular populations increased except for the CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 EPCs population, while in group 2 (VE/VCO2 ≥ 32.5) all endothelial cellular populations increased (Table 3). No differences in the mobilization of endothelial cellular populations between the two severity groups were observed (Table 3).

| Endothelial cellular populations | Group 1 of n = 27, VE/VCO2 slope < 32.5 | Group 2 of n = 22, VE/VCO2 slope ≥ 32.5 | P value between groups | ||

| Before CPET | After CPET | Before CPET | After CPET | ||

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133+ | 62 (41-81) | 95 (81-118)e | 31 (18-66) | 70 (33-99)e | 0.711 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 | 1 (1-3) | 5 (3-8)e | 2 (1-4) | 5 (3-8)e | 0.311 |

| CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 | 10 (7-16) | 13 (10-18) | 12 (8-18) | 16 (9-29)b | 0.134 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133- | 222 (147-287) | 419 (267-576)e | 198 (152-376) | 382 (249-794)e | 0.540 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 | 1 (1-2) | 3 (2-5)e | 1 (1-2) | 4 (3-6)e | 0.464 |

Finally, for severity groups divided according to their EF, they both increased the mobilization of their endothelial cellular populations after maximal CPET (Table 4). In group 1 (EF < 40%), all endothelial cellular populations increased, while in group 2 (EF ≥ 40%) all endothelial cellular populations increased except for the CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 EPCs population (Table 4). No differences in the mobilization of endothelial cellular populations between the two severity groups were observed (Table 4).

| Endothelial cellular populations | Group 1 of n = 37, EF < 40% | Group 2 of n = 12, EF ≥ 40% | P value between groups | ||

| Before CPET | After CPET | Before CPET | After CPET | ||

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133+ | 42 (22-75) | 90 (37-106)e | 63 (40-76) | 90 (65-103)b | 0.888 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 | 2 (1-3) | 5 (3-8)e | 2 (1-4) | 8(4-8)b | 0.507 |

| CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2 | 11 (7-17) | 14 (10-23)b | 15 (9-20) | 13 (9-22) | 0.473 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133- | 200 (152-279) | 427 (260-626)e | 227 (135-372) | 336 (214-624)b | 0.702 |

| CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 | 1 (1-2) | 3 (2-6)e | 1 (1-2) | 3 (2-5)b | 0.828 |

A positive correlation between percentage difference in CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 population and peak VO2 was observed (r = 0.341, P = 0.017), while the numeric difference in the same population tended also to correlate positively (r = 0.252, P = 0.081, Supplementary Table 5). We defined new groups of patients according to the median value of the percentage increase of each endothelial cellular population’s mobilization. It was revealed that demographics and CPET indices did not differ between the two groups for all endothelial cellular populations except for CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 EPCs. Patients with greater increase of this latter EPC population after exercise were younger, had higher peak VO2 and work rate peak and lower VE/VCO2 slope (Supplementary Table 6).

Our present study demonstrated that a symptom-limited maximal CPET exercise stimulates the mobilization of EPCs and CECs in patients with CHF. However, the results of our study did not show any clear association of EPCs and CECs mobilization and CHF severity.

Attenuated endothelial function has been previously associated with decreased EPCs[21], and EPCs have been linked to the repair mechanism of endothelial damage[10,11].

To our knowledge only one single study has been conducted so far investigating the acute effect of maximal exercise on vascular endothelial function in patients with CHF and most specifically on the EPC populations[22]. This was the study of Van Craenenbroeck et al[22], who has investigated the effect of a single exercise bout in reversing endothelial dysfunction in CHF patients. Although Van Craenenbroeck et al[22] have shown a significant improvement in circulating angiogenic cell migratory capacity after exercise, they did not notice a significant increase in EPCs. In the present study, we extend previous findings showing that there is a significant EPCs mobilization after a symptom-limited maximal CPET in patients with CHF, but there was no significant difference between CHF severity groups. An explanation of these differences between the two studies may be the fact that we used different inclusion criteria and parameters for patient severity. In contrast with Van Craenenbroeck et al[22], who divided patients according to N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels, in our study, we divided patients according to strong prognostic indicators such as peak VO2, predicted peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope and EF. Another possible explanation of the differences might be the methodology used in our study for the EPC quantification. In our study, we have used a more analytic EPC quantification with five endothelial populations defined with the use of four monoclonal antibodies, whereas Van Craenenbroeck et al[22] used two populations of endothelial cells for their determination (defined as CD34+/KDR+/CD3- and CD34+/CD3- progenitor cells).

In a previous study from our institute, Stefanou et al[23] quantified three populations of EPCs in critically ill patients with sepsis including CD34+/CD45-/CD133+, CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 and CD34+/CD45-/VEGFR2. In that study, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, considered as an alternative method of exercise, was applied to these patients showing that it could stimulate the mobilization of EPCs in all of the cellular populations mentioned. The findings of the Stefanou et al[23] study is in agreement with our findings as we also observed a mobilization of EPCs in all cellular populations after a single session of exercise training.

The novel insight of our study, in comparison with previous studies, is the assessment of the acute mobilization of EPCs after maximal exercise according to CHF severity by using strong prognostic CPET parameters such as peak VO2 and VE/VCO2 slope. An interesting finding from our study was that those patients who had a greater increase in a single EPCs population (i.e. CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2 cells population) were younger and had better CPET performance. The underlying mechanism of this finding cannot be discerned from the present study; secreting cytokines such as VEGF might interact more with this particular EPC population, and its secretion might be related with the degree of endothelium damage and the exercise stimuli. However, further study is needed to investigate this finding.

The present study has also introduced a more analytic methodology to quantify and define EPCs and CECs compared to previous studies. EPCs and CECs are being used as an index of the endothelium restoration potential and to reflect vascular endothelial function[10]. In our study, a large number of endothelial cellular populations was defined and quantified: Three groups of EPCs (CD34+/CD45-/CD133+, CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2 and CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2) and two groups of CECs (CD34+/CD45-/CD133- and CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2) broadened our knowledge of the phenotype of endothelial cellular populations. Monoclonal antibodies such as CD45, CD34, CD133 and VEGFR2 (CD309) are the most widely used for the definition of EPC and CEC phenotypes[20,24,25]. Other monoclonal antibodies such as CD146, CD105 and CD144 have been previously used, however, without providing more information or specialization in EPC or CEC phenotypes[24,26].

CHF is characterized by increased inflammatory status, endothelial dysfunction and impaired microcirculation, which are crucially involved in development and progression of the disease[27]. Impaired endothelium dependent vasodilatation, in addition to impaired cardiac function, is a main determinant of exercise intolerance in patients with CHF, limiting physical exercise capacity and deteriorating peak aerobic capacity[6,7,27]. Exercise has been reported to increase blood flow and shear stress, therefore increasing endothelial NOS activity and NO production and reducing inflammation[28]. Patients with CHF usually have a different level of deterioration of their vascular endothelium. However, through the present study, exercise was shown to enhance the acute mobilization of EPCs and CECs in these patients in a similar beneficial way, irrespectively of their severity. Targeting endothelial dysfunction could be a breakthrough therapy as endothelial function is recognized as a crucial component underlying HF.

Regarding the potential mechanisms of the mobilization of EPCs, shear stress could be suggested as a triggering factor for their release after a symptom limited maximal CPET. Shear stress seems to upregulate the activity of endothelial NO synthase and increase the production of NO[29,30]. Moreover, the activation of ion, cation and stretch sensitive channels and a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ have been observed in endothelial cells immediately after exposure to shear stress[29,30]. All these endothelial functions contribute to the amplified number and activity of circulating EPCs, and they could play a role in signaling to the cell that it is under shear and eliciting a response[29,30].

Another possible mechanism that may be suggested is the ischemic/hypoxic stimulus. Ischemic/hypoxic stimulus has been shown to increase EPCs count in short-term studies enrolling patients with cardiovascular disease[31] and in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease[32]. Exercise has the potential to induce hypoxic stimuli, as suggested by alterations in microcirculation indices during exercise sessions in healthy populations and patients with cardiovascular comorbidities[33,34]. These mechanisms may relate to up-regulation of transcriptional factors, such as matrix metalloproteinases, stromal cell-derived factor 1 and vascular endothelial growth factor, which mediate processes to promote proliferative and migratory capacities of circulating EPCs[22,32,34].

Our study had certain limitations. This was a post-hoc analysis study not designed to compare CHF groups, making our analysis underpowered for group comparison. However, this is the larger sample size tested and analyzed to date and provides significant results according to CHF severity. Our results cannot be generalized to all CHF populations. We excluded patients with unstable and/or decompensated heart failure due to the inability to perform maximal CPET ,and for this reason our findings cannot be applied in such cohort of patients.

On the other hand, our study broadens horizons for future fields of research. The function and role of each cellular population in the vascular endothelium, the relationship between cellular populations, local and systemic neurohumoral factors and cytokines or other vascular endothelium factors and exercise modalities (type, intensity, duration, volume) merits further investigation. Furthermore, other non-invasive methodologies reflecting endothelium function and microcirculation such as flow mediated dilation and near-infrared spectroscopy should be tested and investigated in relationship to EPC measurements to provide potential indirect evaluation of bone marrow response.

In conclusion, a single symptom-limited maximal CPET induces a significant mobilization of EPCs and CECs in CHF patients, but there was no significant association with disease severity.

Vascular endothelial dysfunction is an underlying pathophysiological feature of chronic heart failure (CHF). Patients with CHF are characterized by impaired vasodilation and inflammation of the vascular endothelium. They also have low levels of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). EPCs have been used as an index of the endothelium restoration potential, therefore reflecting the vascular endothelial function. Exercise has a beneficial impact in the function of the vascular endothelium and EPCs.

Despite the proven beneficial effect of exercise training in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, the effect of maximal exercise on EPCs in patients with CHF, and especially in patients of different severity, remains under investigation.

This study was conducted to assess, quantify and compare the acute mobilization of EPCs after maximal exercise in patients with CHF of both lower and higher severity.

Forty-nine consecutive patients with stable CHF underwent a cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) on a cycle ergometer. Venous blood was sampled before and after CPET. Five circulating endothelial populations were quantified by flow cytometry. Patients were divided in two groups of severity according to the median value of peak oxygen uptake (VO2), predicted peak VO2, ventilation (VE)/carbon dioxide output (VCO2) slope and ejection fraction (EF).

Patients with lower peak VO2 increased the mobilization of CD34+/CD45-/CD133+, CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2, CD34+/CD45-/CD133- and CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2, while patients with higher VO2 increased the mobilization of CD34+/CD45-/CD133+, CD34+/CD45-/CD133+/VEGFR2, CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2, CD34+/CD45-/CD133- and CD34+/CD45-/CD133-/VEGFR2. A similar increase in the mobilization of at least four out of five cellular populations was observed after maximal exercise within each severity group regarding predicted peak, VE/VCO2 slope and EF, as well (P < 0.05). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the mobilization of endothelial cellular populations between severity groups in each comparison (P > 0.05).

Our study has shown an increased EPC and CEC mobilization after maximal exercise in CHF patients, but this increase was not associated with syndrome severity.

EPCs could be the cornerstone to the treatment of CHF. Understanding their possible mechanisms of action on vascular endothelial function through exercise would create innovative ideas regarding their distribution and proliferation in these patients in order to take advantage of their beneficial effects on the endothelium and reverse cardiac remodeling.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pan SL S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Ceia F, Fonseca C, Mota T, Morais H, Matias F, de Sousa A, Oliveira A; EPICA Investigators. Prevalence of chronic heart failure in Southwestern Europe: the EPICA study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4:531-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Taylor CJ, Roalfe AK, Iles R, Hobbs FD. Ten-year prognosis of heart failure in the community: follow-up data from the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening (ECHOES) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:176-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4368] [Cited by in RCA: 4921] [Article Influence: 546.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Kovačić S, Plazonić Ž, Batinac T, Miletić D, Ružić A. Endothelial dysfunction as assessed with magnetic resonance imaging - A major determinant in chronic heart failure. Med Hypotheses. 2016;90:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Manetos C, Dimopoulos S, Tzanis G, Vakrou S, Tasoulis A, Kapelios C, Agapitou V, Ntalianis A, Terrovitis J, Nanas S. Skeletal muscle microcirculatory abnormalities are associated with exercise intolerance, ventilatory inefficiency, and impaired autonomic control in heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1403-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | MacIver DH, Dayer MJ, Harrison AJ. A general theory of acute and chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Bailey DM, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: effects of antioxidants and exercise training in elderly men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H671-H678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Koutroumpi M, Dimopoulos S, Psarra K, Kyprianou T, Nanas S. Circulating endothelial and progenitor cells: Evidence from acute and long-term exercise effects. World J Cardiol. 2012;4:312-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sawyer BJ, Tucker WJ, Bhammar DM, Ryder JR, Sweazea KL, Gaesser GA. Effects of high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training on endothelial function and cardiometabolic risk markers in obese adults. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2016;121:279-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Morrone D, Felice F, Scatena C, De Martino A, Picoi MLE, Mancini N, Blasi S, Menicagli M, Di Stefano R, Bortolotti U, Naccarato AG, Balbarini A. Role of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in the reparative mechanisms of stable ischemic myocardium. Int J Cardiol. 2018;257:243-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chan KH, Simpson PJ, Yong AS, Dunn LL, Chawantanpipat C, Hsu C, Yu Y, Keech AC, Celermajer DS, Ng MK. The relationship between endothelial progenitor cell populations and epicardial and microvascular coronary disease-a cellular, angiographic and physiologic study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujisue K, Sugiyama S, Matsuzawa Y, Akiyama E, Sugamura K, Matsubara J, Kurokawa H, Maeda H, Hirata Y, Kusaka H, Yamamoto E, Iwashita S, Sumida H, Sakamoto K, Tsujita K, Kaikita K, Hokimoto S, Matsui K, Ogawa H. Prognostic Significance of Peripheral Microvascular Endothelial Dysfunction in Heart Failure With Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Circ J. 2015;79:2623-2631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen YC, Ho CW, Tsai HH, Wang JS. Interval and continuous exercise regimens suppress neutrophil-derived microparticle formation and neutrophil-promoted thrombin generation under hypoxic stress. Clin Sci (Lond). 2015;128:425-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Werner N, Kosiol S, Schiegl T, Ahlers P, Walenta K, Link A, Böhm M, Nickenig G. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:999-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1596] [Cited by in RCA: 1591] [Article Influence: 79.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Samman Tahhan A, Hammadah M, Sandesara PB, Hayek SS, Kalogeropoulos AP, Alkhoder A, Mohamed Kelli H, Topel M, Ghasemzadeh N, Chivukula K, Ko YA, Aida H, Hesaroieh I, Mahar E, Kim JH, Wilson P, Shaw L, Vaccarino V, Waller EK, Quyyumi AA. Progenitor Cells and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kourek C, Karatzanos E, Psarra K, Ntalianis A, Mitsiou G, Delis D, Linardatou V, Pittaras T, Vasileiadis I, Dimopoulos S, Nanas S. Endothelial progenitor cells mobilization after maximal exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2020;Online ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | American Thoracic Society; American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:211-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2035] [Cited by in RCA: 2313] [Article Influence: 105.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hansen JE, Sue DY, Wasserman K. Predicted values for clinical exercise testing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:S49-S55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 654] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nanas S, Anastasiou-Nana M, Dimopoulos S, Sakellariou D, Alexopoulos G, Kapsimalakou S, Papazoglou P, Tsolakis E, Papazachou O, Roussos C, Nanas J. Early heart rate recovery after exercise predicts mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:393-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Duda DG, Cohen KS, Scadden DT, Jain RK. A protocol for phenotypic detection and enumeration of circulating endothelial cells and circulating progenitor cells in human blood. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:805-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu J, Hu DJ, Yan H, Liu J, Ai X, Ren Z, Zeng H, He H, Yang Z. Attenuated endothelial function is associated with decreased endothelial progenitor cells and nitric oxide in premenopausal diabetic women. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:4666-4674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Van Craenenbroeck EM, Beckers PJ, Possemiers NM, Wuyts K, Frederix G, Hoymans VY, Wuyts F, Paelinck BP, Vrints CJ, Conraads VM. Exercise acutely reverses dysfunction of circulating angiogenic cells in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1924-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stefanou C, Karatzanos E, Mitsiou G, Psarra K, Angelopoulos E, Dimopoulos S, Gerovasili V, Boviatsis E, Routsi C, Nanas S. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation acutely mobilizes endothelial progenitor cells in critically ill patients with sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huizer K, Mustafa DAM, Spelt JC, Kros JM, Sacchetti A. Improving the characterization of endothelial progenitor cell subsets by an optimized FACS protocol. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fadini GP, Losordo D, Dimmeler S. Critical reevaluation of endothelial progenitor cell phenotypes for therapeutic and diagnostic use. Circ Res. 2012;110:624-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Djohan AH, Sia CH, Lee PS, Poh KK. Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Heart Failure: an Authentic Expectation for Potential Future Use and a Lack of Universal Definition. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2018;11:393-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shirazi LF, Bissett J, Romeo F, Mehta JL. Role of Inflammation in Heart Failure. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2017;19:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pearson MJ, Smart NA. Aerobic Training Intensity for Improved Endothelial Function in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiol Res Pract. 2017;2017:2450202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tao J, Yang Z, Wang JM, Tu C, Pan SR. Effects of fluid shear stress on eNOS mRNA expression and NO production in human endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiology. 2006;106:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang Z, Wang JM, Chen L, Luo CF, Tang AL, Tao J. Acute exercise-induced nitric oxide production contributes to upregulation of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in healthy subjects. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:452-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sandri M, Adams V, Gielen S, Linke A, Lenk K, Kränkel N, Lenz D, Erbs S, Scheinert D, Mohr FW, Schuler G, Hambrecht R. Effects of exercise and ischemia on mobilization and functional activation of blood-derived progenitor cells in patients with ischemic syndromes: results of 3 randomized studies. Circulation. 2005;111:3391-3399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sandri M, Beck EB, Adams V, Gielen S, Lenk K, Höllriegel R, Mangner N, Linke A, Erbs S, Möbius-Winkler S, Scheinert D, Hambrecht R, Schuler G. Maximal exercise, limb ischemia, and endothelial progenitor cells. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tzanis G, Manetos C, Dimopoulos S, Vasileiadis I, Malliaras K, Kaldara E, Karatzanos E, Nanas S. Attenuated Microcirculatory Response to Maximal Exercise in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2016;36:33-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ross MD, Wekesa AL, Phelan JP, Harrison M. Resistance exercise increases endothelial progenitor cells and angiogenic factors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |