Copyright

©2014 Baishideng Publishing Group Inc.

World J Cardiol. Jun 26, 2014; 6(6): 478-494

Published online Jun 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i6.478

Published online Jun 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i6.478

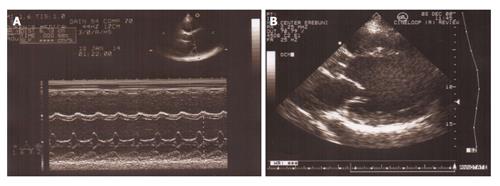

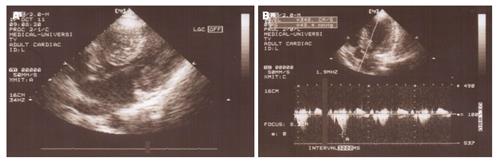

Figure 1 M mode and B mode echocardiogram of patient with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.

A: M mode echocardiogram shows dilated left ventricle with hypokinesis of interventricular septum and posterior wall; B: Parasternal long axis view of B mode echocardiogram showing remodeled left ventricular shape with loss of elliptical form.

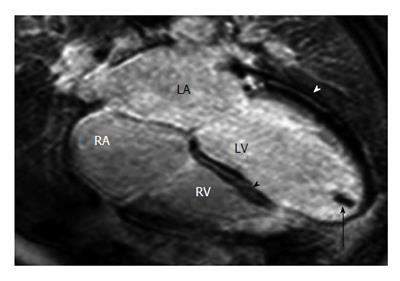

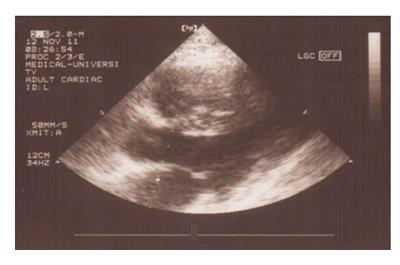

Figure 2 Dilated cardiomyopathy in a 36-year-old male soccer player with fatigue and a 3-5-d history of burning epigastric pain associated with nausea, vomiting, and early satiety[105].

Horizontal long-axis late contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging shows an apical thrombus (arrow) in the left ventricle (LV) and midwall enhancement in the lateral left ventricular wall (white arrowhead) and the interventricular septum (black arrowhead). RA: Right atrium; RV: Right ventricle; LA:Left atrium.

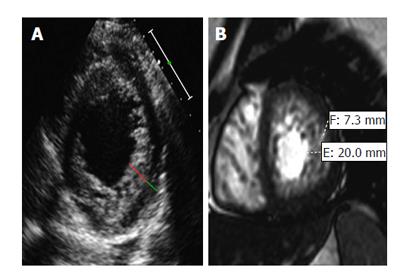

Figure 3 Non-compaction cardiomyopathy in two patients[105].

A: Dilated cardiomyopathy in a 60-year-old man with new-onset congestive heart failure. Short-axis echocardiogram obtained in systole at the level of the left ventricle (LV) shows a two-layered myocardium with a noncompacted (red line) and com¬pacted (green line) layer along the lateral, inferior, and anterior walls and a maximal end-systolic NC: C ratio > 2; B: Symptoms of New York Heart Association Class III heart failure and severely reduced (≤ 35%) LV ejection fraction in a 35-year-old woman. Short-axis 2D SSFP cardiac magnetic resonance imaging obtained in end diastole shows thickening of the noncompacted layer of the LV myocardium, with an NC: C ratio of 2.9. The patient underwent subsequent implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

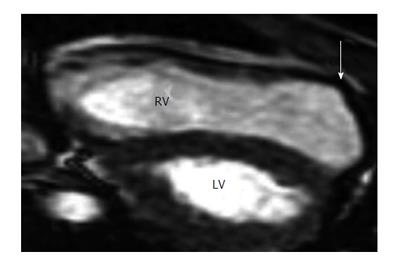

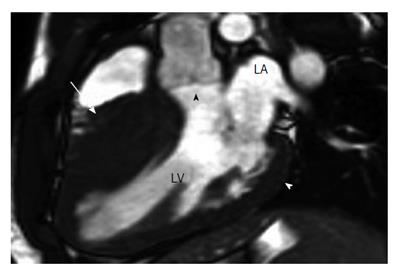

Figure 4 Arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy in a 17-year-old boy who experienced sudden cardiac death from sustained ventricular tachycardia during a soccer match and was revived with on-site defibrillation[105].

Parasternal long-axis 2D echocardiograms obtained in end systole show a dilated right ventricle (RV) and regional dyskinesis at the RV outlet tract (arrow). LV: left ventricle.

Figure 5 Patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and subaortic stenosis.

A: Parasternal long axis view showing expressed left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy at the region of the LV outflow tract; B: Doppler echocardiogram reveals the high subaortic gradient (ΔP = 48 mmHg).

Figure 6 Echocardiogram of a 35-year-old patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: massive hypertrophy of the interventricular septum with wall thickness 37 mm compared to posterior wall; hyperechogenic septal myocardium.

Figure 7 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy[105].

A: 2D SSFP cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, obtained in end diastole in the long-axis plane of the LV outflow tract (LVOT) in a 17-year-old boy with Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy found at family screening, shows marked asymmetric septal hypertrophy with a ratio of ventricular septal thickness (27 mm, arrow) to inferiolateral wall thickness (9 mm, white arrowhead) of 3:1. Note that the hypertrophied septum encroaches on the LV lumen, causing mild narrowing of the LVOT (black arrowhead). LA: Left atrium; LV: Left ventricle.

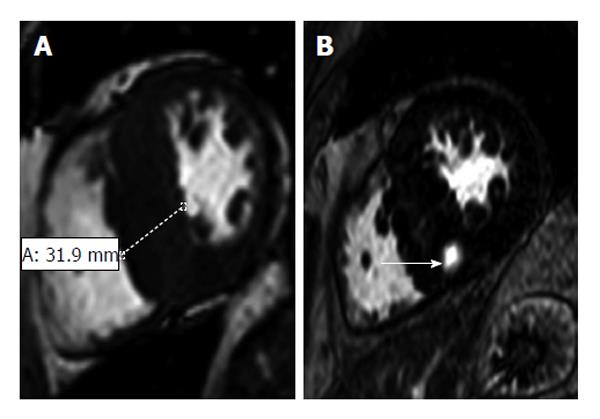

Figure 8 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a 57-year-old man with a 2-year history of exertional dyspnea and chest discomfort who underwent implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death[105].

A: Short-axis 2D SSFP magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed in end diastole shows asymmetric septal hypertrophy with a maximal thickness of 31.9 mm encroaching on the ventricular lumen; B: Short-axis late contrast-enhanced MRI shows a patchy nodular area of enhancement in the hypertrophied septum (arrow) that does not correspond to a coronary artery territory and, therefore, is distinctly different from an infarct scar.

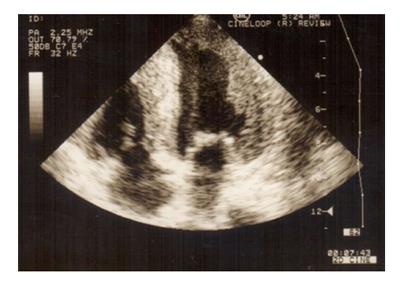

Figure 9 Patient with secondary cardiac amyloidosis due to familial Mediterranean fever.

Echocardiogram shows hypertrophic amyloid infiltration and increased hyperechogenic “granular sparkling” myocardium with increased myocardial wall thickness.

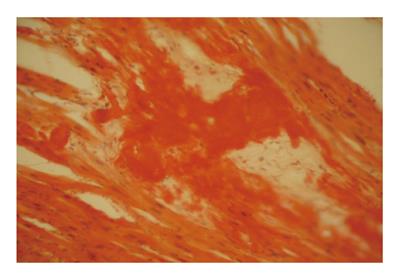

Figure 10 Amyloid deposits in myocardium in patient with secondary amyloidosis due to familial Mediterranean fever.

Autopsy study with Congo-Red-positive extracellular deposits, causing disorder of myocardial organization.

- Citation: Sisakian H. Cardiomyopathies: Evolution of pathogenesis concepts and potential for new therapies. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(6): 478-494

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i6/478.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i6.478