Copyright

©The Author(s) 2018.

World J Cardiol. Nov 26, 2018; 10(11): 201-209

Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v10.i11.201

Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v10.i11.201

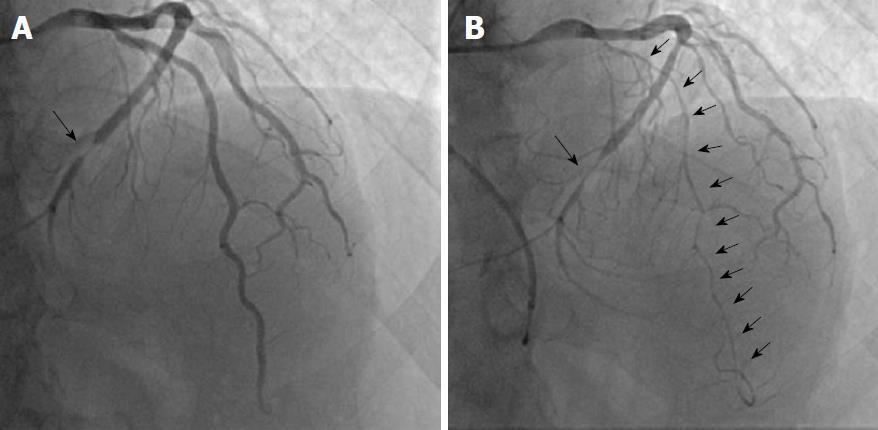

Figure 1 A representative case with coronary spasm and coronary stenosis.

The patient, who had chest symptoms for 20 min at rest, accompanied with cold sweating, was admitted to our institution for the evaluation of his chest symptoms. A: Coronary angiography showed coronary stenosis at the distal segment of the left circumflex coronary artery, which cannot be considered as the cause of his chest symptoms; B: The spasm provocation test using 100 µg of acetylcholine showed diffuse coronary spasm throughout the left anterior descending coronary artery, accompanied with usual chest pain, which had been restored after nitroglycerin injection. Coronary stenosis and spastic segments were indicated by bold arrow and plain arrows, respectively.

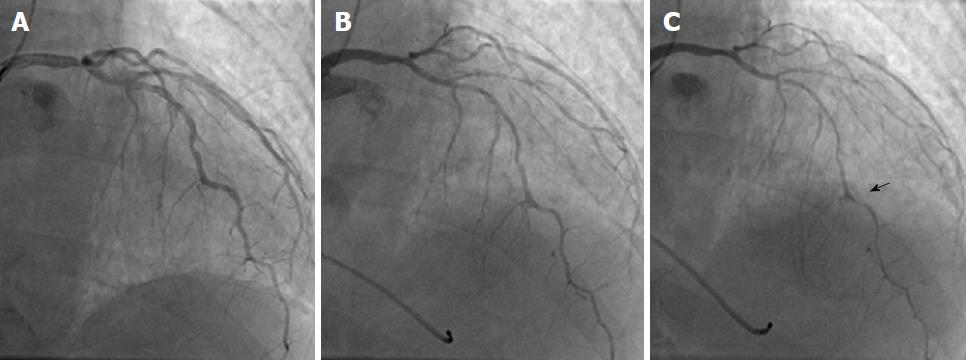

Figure 2 A case of coronary spasm, which was documented by sequential spasm provocation test, which was performed after the routine coronary angiography, vasodilator administration, and preprocedural infusion of nitroglycerin.

A: The patient had chest symptoms at exercise early in the morning. Coronary computed tomography angiography showed stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. However, the coronary angiography showed no significant coronary stenosis; B: Because the presence of vasospastic angina was suspicious, the spasm provocation test was performed despite the intracoronary infusion of nitroglycerin and calcium channel blocker intake. The standard doses of acetylcholine (ACh, up to maximal 200 μg) did not cause coronary spasm; C: Consequently, we performed the sequential spasm provocation test: 120 μg of ergonovine maleate was infused first followed by 200 μg of ACh, showing the presence of coronary spasm (right panel) and obtained the diagnosis of vasospastic angina. The spastic site was indicated by an arrow. Ach: Acetylcholine; EM: Ergonovine maleate.

- Citation: Teragawa H, Oshita C, Ueda T. Coronary spasm: It’s common, but it’s still unsolved. World J Cardiol 2018; 10(11): 201-209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v10/i11/201.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v10.i11.201