Published online May 27, 2021. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v12.i3.38

Peer-review started: October 25, 2020

First decision: December 24, 2020

Revised: January 6, 2021

Accepted: February 25, 2021

Article in press: February 25, 2021

Published online: May 27, 2021

Processing time: 212 Days and 13.7 Hours

Tubulins, building blocks of microtubules, are modified substrates of diverse post-translational modifications including phosphorylation, polyglycylation and polyglutamylation. Polyglutamylation of microtubules, catalyzed by enzymes from the tubulin tyrosine ligase-like (TTLL) family, can regulate interactions with molecular motors and other proteins. Due to the diversity and functional importance of microtubule modifications, strict control of the TTLL enzymes has been suggested.

To characterize the interaction between never in mitosis gene A-related kinase 5 (NEK5) and TTLL4 proteins and the effects of TTLL4 phosphorylation.

The interaction between NEK5 and TTLL4 was identified by yeast two-hybrid screening using the C-terminus of NEK5 (a.a. 260–708) as bait and confirmed by immunoprecipitation. The phosphorylation sites of TTLL4 were identified by mass spectrometry and point mutations were introduced.

Here, we show that NEK5 interacts with TTLL4 and regulates its polygluta

Our results demonstrate, for the first time, the regulation of TTLL activity through phosphorylation, pointing to NEK5 as a potential effector kinase. We also suggest a general control of tubulin polyglutamylation through NEK family members in human cells.

Core Tip: Tubulins are modified extensively by post-translational processes such as polyglutamylation. Considering the diversity of microtubule polyglutamylation and the existence of many non-tubulin substrates, it is important to understand how the effector enzymes, the tubulin ligase-like (TTLL) proteins, are regulated. TTLL4 interacts with never in mitosis gene A (NIMA)-related kinase 5, a member of the mitotic NIMA-related kinases. We demonstrate that NIMA-related kinase 5 is a potential regulator of polyglutamylation through the control of TTLL4 activity. Here we show, for the time, the regulation of TTLL4 activity through phosphorylation, and demonstrate the potential control of polyglutamylation through NEK family members in human cells.

- Citation: Melo-Hanchuk TD, Kobarg J. Polyglutamylase activity of tubulin tyrosine ligase-like 4 is negatively regulated by the never in mitosis gene A family kinase never in mitosis gene A -related kinase 5. World J Biol Chem 2021; 12(3): 38-51

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8454/full/v12/i3/38.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v12.i3.38

The microtubule cytoskeleton is essential for the internal organization of eukaryotic cells and is involved in cell division, differentiation and active transport processes. The great diversity of tubulin inside the cells is due to the expression of tubulin isotypes and a large array of post-translational modifications including acetylation/deace

Polyglutamylation was initially discovered in tubulins and consists of the addition of glutamate side chains to acceptor glutamate residues in the main chain of the modified proteins[1,2]. Glutamylation is found on microtubules of cilia and flagella[6], centrioles, basal bodies and centrosomes[7]. The levels of glutamylated tubulin of the mitotic spindle are increased during cell division[8-10].

In vitro experiments have shown that polyglutamylation of α- or β-tubulin can act as a regulator of microtubule interactions with microtubule-associated proteins[11,12] and motor proteins[11,13-15]. The enzymes responsible for polyglutamylation are members of the tubulin ligase-like (TTLL) family[16,17]. Their name is derived from tubulin tyrosine ligase[18], a related tubulin-modifying enzyme[19], with which they share a strong sequence homology. A total of nine enzymes that can catalyze polyglutamylation have been identified[16,17]. TTLL4, 5, 6, 7, 11, and 13 generate tubulin glutamylation when overexpressed in mammalian cells. Studies of the catalytic activity of TTLL family members revealed that these enzymes have intrinsic preferences for either α- or β-tubulin and for the generation of either short or long glutamate chains[17]. Polyglutamylation is not restricted to tubulins. Several sub

Kinases are key regulators of many cellular processes, and could thus also be potential regulators of polyglutamylases. The never in mitosis gene A (NIMA)-related kinases (NEKs) are mammalian enzymes, which were identified by their high identity (40%-45%) to the Aspergillus nidulans mitotic protein NIMA within their catalytic domain[22-24]. In humans, the NEK family is represented by 11 members that have been functionally associated to one of the three core functions established for this family in mammals: (1) Centrioles/mitosis; (2) Primary ciliary function/ciliopathies; and (3) Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage response[25].

The participation of NEKs in the microtubule-related process is broadly described; however, the first link with polyglutamylation was identified during the purification of polyglutamylase from the protist Crithidia fasciculata[26]. Purified extracts of NIMA-related kinase were capable of glutamylating tubulins in vitro. The later discovery of TTLLs as tubulin polyglutamylases strongly suggested that extracts of NIMA-related kinase were associated with a Crithidia fasciculata TTLL enzyme.

Here, we describe the identification and confirmation of the interaction between NEK5 and TTLL4. This prompted us to investigate the activity of TTLL4. In a broader context, our analysis showed, for the first time, a mechanism for direct regulation of a glutamylase from the TTLL family through phosphorylation, pointing to NEK5 as a potential candidate as an effector kinase.

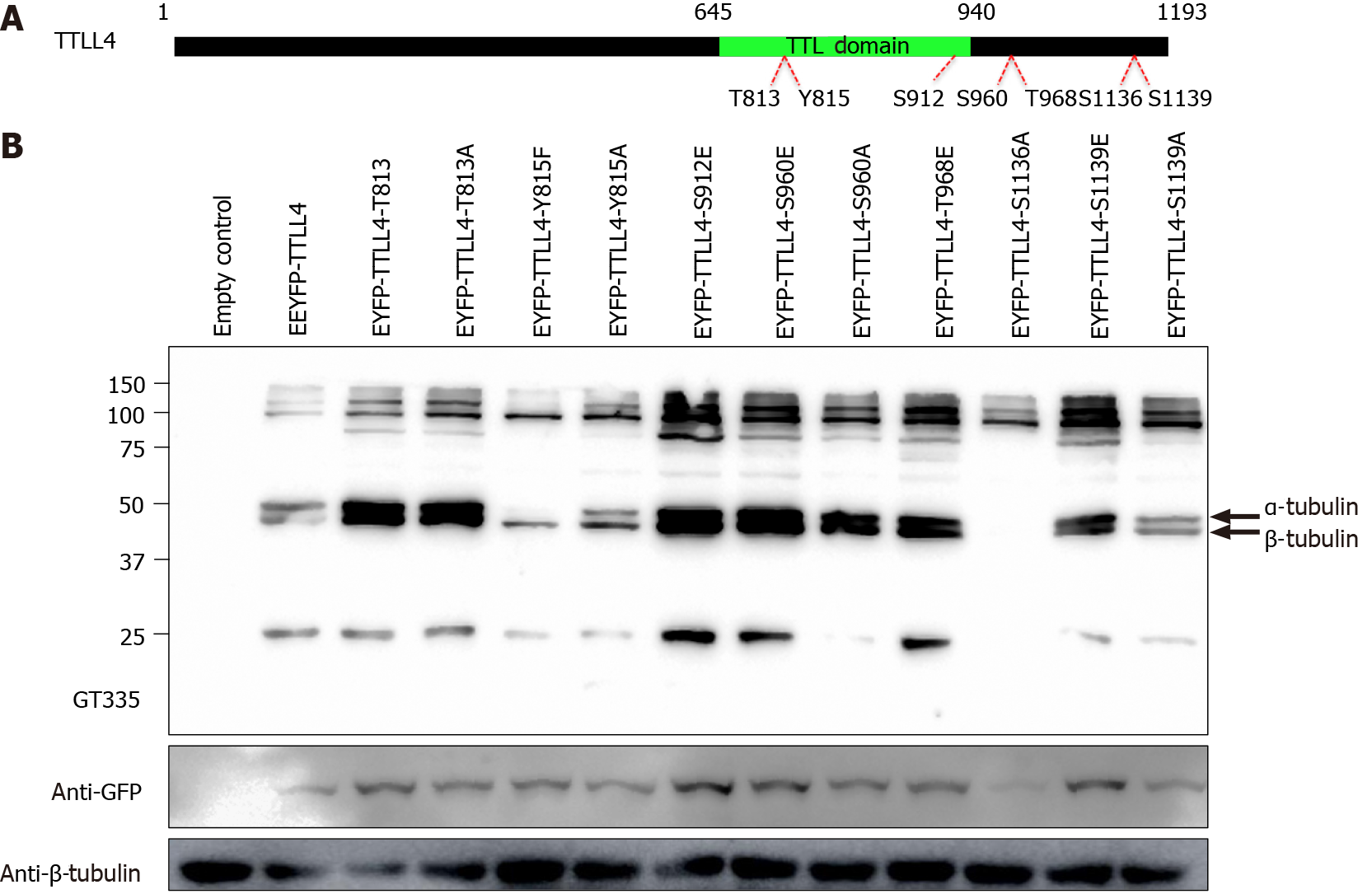

TTLL4 full size, TTLL4 C347-1193, TTLL4 C555-1193, TTLL4 C606-1193, TTLL5, TTLL5 N800 and TTLL7 genes were amplified from mouse brain or testis complementary DNA (cDNA) and previously cloned in a vector containing a C-terminal enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) tag[17]. The TLL domains of TTLL4, TTLL5 and TTLL7 have many conserved residues (Supplementary Figure 1). TTLL5 N800 corresponds to the first 800 N-terminal amino acids and TTLL5 is the full size, but both are active versions of TTLL5. Point mutations were introduced by the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA, United States) to generate the NEK5-kinase-dead (NEK5-KD) (K33A-inactive mutant of NEK5), TTLL4-T813E, TTLL4-T815A, TTLL4-Y815F, TTLL4-Y815A, TTLL4-S912E, TTLL4-S960E, TTLL4-S960A, TTLL4-T968E, TTLL4-S1136A, TTLL4-S1139E and TTLL4-S1136A. All mutants were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The production of HEK293 silenced for NEK5 was carried out by short hairpin ribonucleic acid (shRNA) lentiviral particles (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Incorporated). Stable cells were obtained with the Flp-In. System. The procedure to obtain all the cell lines has been described previously[27]. Stable cells expressing NEK5 were used as controls.

The following antibodies were used for both immunoprecipitation and Western blot assay: mouse anti-NEK5 (SC130492), mouse anti-green fluorescent proteins (GFP) (G1546), mouse GT335 (Adipogen) and anti-TTLL4 (Novus Biologicals).

The cDNA encoding the C-terminus of NEK5 (a.a. 260–708) was cloned in the pGBKT7. The yeast two-hybrid screen was performed following the Matchmaker™ Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System (Clontech Laboratories, Incorporated, Mountain View, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Selective medium without tryptophan, leucine, adenine and histidine but containing aureobasidin A antibiotic and X-α-Gal was used to screen interactors from the human universal cDNA library. To identify the “prey” genes, the DNA was extracted and sequenced.

TTLL genes amplified from mouse brain or testis cDNA were used because mouse proteins show a better expression level. Mouse and human TTLL4 protein are very similar and share 79.98% identity and 85.80% similarity (Supplementary Figure 2). Expression plasmids were transfected using JetPEI (Polyplus transfection) or homemade PEI.

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany), subjected to freeze/thaw, submitted to three cycles of 5 min in an ultrasound bath (UltraSonic Clear 750, UNIQUE) for complete pellet suspension and centrifuged at 20000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method[28]. The supernatants were used for immunoprecipitation. Briefly, the supernatant was added to GFP-Trap® (ChromoTek GmbH, Germany) coupled to agarose beads or anti-NEK5, previously coupled to G-sepharose beads and incubated overnight. The beads were collected, washed five times with wash buffer (10 mmol/L Tris/Cl pH: 7.5; 150 mmol/L NaCl; 0.5 mmol/L ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid) and then eluted with 2 × sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-sample buffer (120 mmol/L Tris/Cl pH: 6.8; 20% glycerol; 4% SDS, 0.04% bromophenol blue; 10%β-mercaptoethanol). The proteins were immunoblotted onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, United States) and probed with antibodies. Blots were developed using an emitter coupled logic (ECL) chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences).

50 µg of protein were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and blotted onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, United States). In the case of mammalian tubulin, a special protocol was used, as described in Eddé et al[1]. The protein bands were probed using the following primary antibodies diluted in 3% bovine serum albumin blocking solution: mouse anti-GFP (1:1000, Sigma), mouse anti-NEK5 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit anti-TTLL4 (1:500, Novus Biologicals). The monoclonal mouse GT335 (anti-polygluta

The proteins from the GFP affinity-purified fraction were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained using Colloidal blue. Protein bands at the expected size for TTLL4 and TTLL5 were excised from the gel and submitted to in-gel trypsin or chymotrypsin digestion. Peptides were concentrated and analyzed by MS/MS on a Q-TOF II mass spectrometer (Micromass Limited, Manchester, United Kingdom). Data analysis was performed with Mascot (Matrix Science Limited, London, United Kingdom) against the National Center for Biotechnology Information database.

Transfected control and shRNA-NEK5 cells were collected and dissociated using trypsin. Cells were suspended in saline solution, passed through a 0.45 µmol/L filter and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gates were created to separate single cells using the FSC and SSC parameters followed by a new gate for yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) positive cells. The sorting was performed by separation in positive and negative YFP cells on a binding domain-FACS Aria flow cytometer using FACS Diva 6.0 software and data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Incorporated, Ashland, OR, United States).

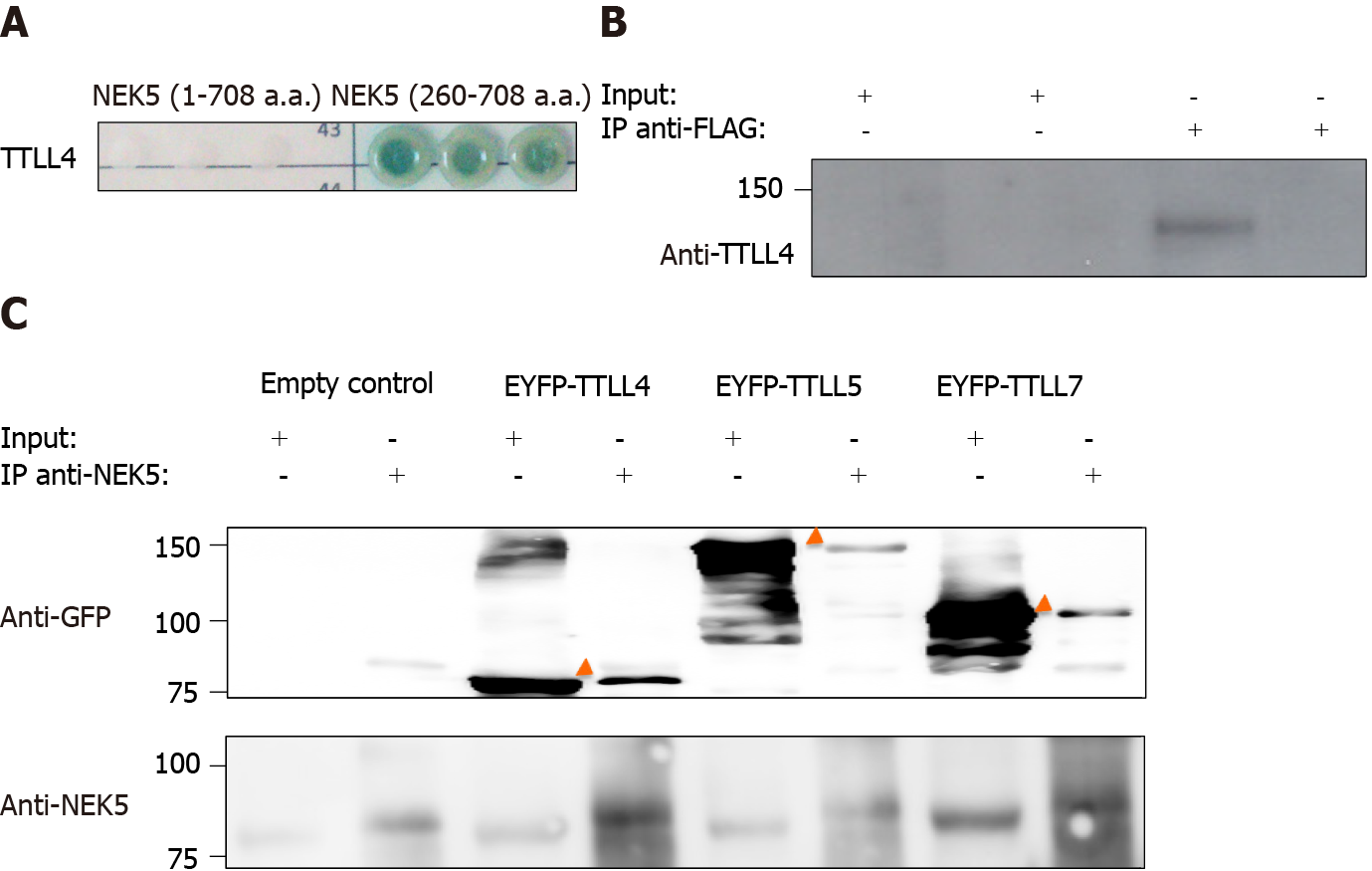

The molecular functions of NEK5 are still not fully elucidated. In order to identify putative functional partners of NEK5, the yeast two-hybrid experiment was performed. The C-terminal fragment of NEK5 (a.a. 260-708) was used as a bait protein fused to the Gal4-DNA binding domain against a human cDNA library. The prey proteins from the library were expressed as a fusion to a Gal4-activation domain (AD)[30,31]. In this stringent protein-protein interaction screen, four independent reporter genes must be activated (AUR1-C, ADE2, HIS3, and MEL1). The screening resulted in the identification of TTLL4 (amino acid residues 895 to 1189) as NEK5’s interactor (Figure 1A). The controls of yeast two-hybrid screening are presented in the supplementary material (Supplementary Figure 3). The interaction between endoge

Polyglutamylase from the TTLL enzyme family displays reaction preferences such as the length of side chains (long or short) and substrates (α- or β-tubulin)[17,32]. TTLL4, TTLL5 and TTLL7 are involved in the initiation of the polyglutamylation chain but with different substrate specificity. While TTLL4 has a preference for α-tubulin and NAP proteins, TTLL5 and TTLL7 have a preference for α- and β-tubulin, respective

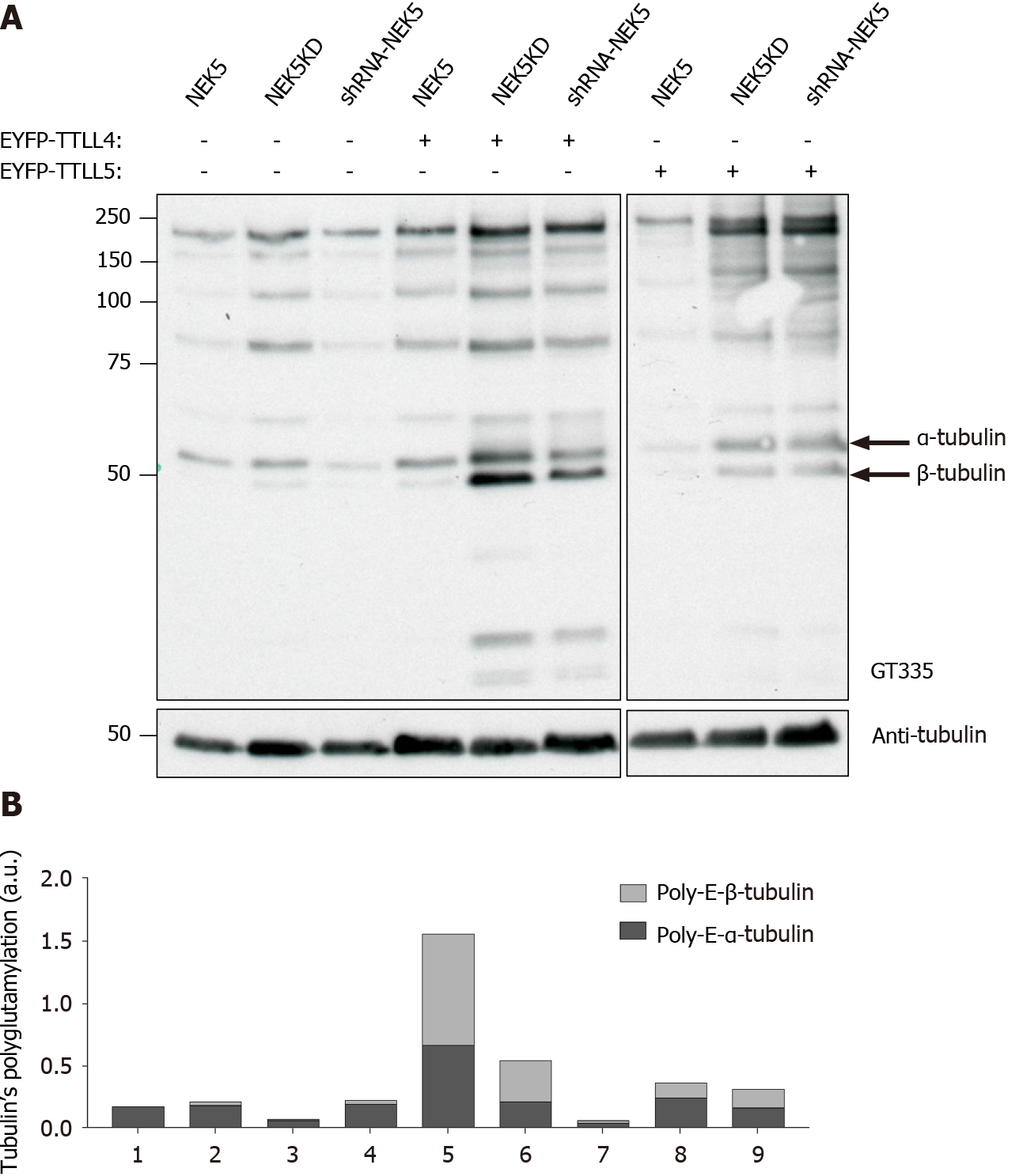

TTLLs are responsible for the polyglutamylation of tubulin as well as other proteins. As we have shown that NEK5 and TTL4 interact (Figure 1A and B), we hypothesized that NEK5 could regulate TTLL4 activity. To confirm this, cells stably expressing the inactive version of NEK5-KD, as well as cells silenced for NEK5 (shRNA-NEK5) and control cells were transfected with TTLL4 and TTLL5 and the polyglutamylation profiles of cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot using GT335, a glutamylation-specific antibody.

Cells expressing NEK5 were used as controls and showed low levels of all the polyglutamylated protein bands (Figure 2A, lane 1). The catalytically inactive NEK5-KD cells, on the other hand, showed increased levels of protein polyglutamylation (Figure 2A, lane 2). The difference in polyglutamylation status between controls vs either shNEK5 knockdown or NEK5-KD was more pronounced upon overexpression of TTLL4 (Figure 2A, compare lane 4 with lane 5 and 6) or TTLL5 (Figure 2A, compare lane 7 with lanes 8 and 9).

TTLL4 and TTLL5 have preferences for glutamylation of β and α-tubulin, respectively[17]. The ratio of α and β glutamylated-tubulin was also altered after TTLL4 and TTLL5 transfection in the presence or absence of functional NEK5. For example, despite the preference of TTLL5 for α-tubulins, upon decreased expression of functional NEK5, cells transfected with TTLL5 showed that not only the level of polyglutamylation of all protein substrates was increased, but β-tubulin also turned out to be an additional new target (Figure 2A, lanes 7 vs 9). TTLL4 on the other hand, even in the absence of NEK5 (Figure 2A, lane 5) or in the presence of catalytically non-functional NEK5 (lane 6) continued to prefer β-tubulin as substrate.

Although only TTLL4 has been identified as a NEK5 interactor in the yeast two-hybrid screen, the inhibitory effects of NEK5 on TTLL activity were also observed on TTLL5, suggesting that, NEK5 may play a regulatory role on more than one member of the TTLL family (Figure 2A). Polyglutamylation levels of other than tubulins have also been altered in the absence of functional NEK5 and upon overexpression of TTLL4 or TTLL5 (Figure 2A and B).

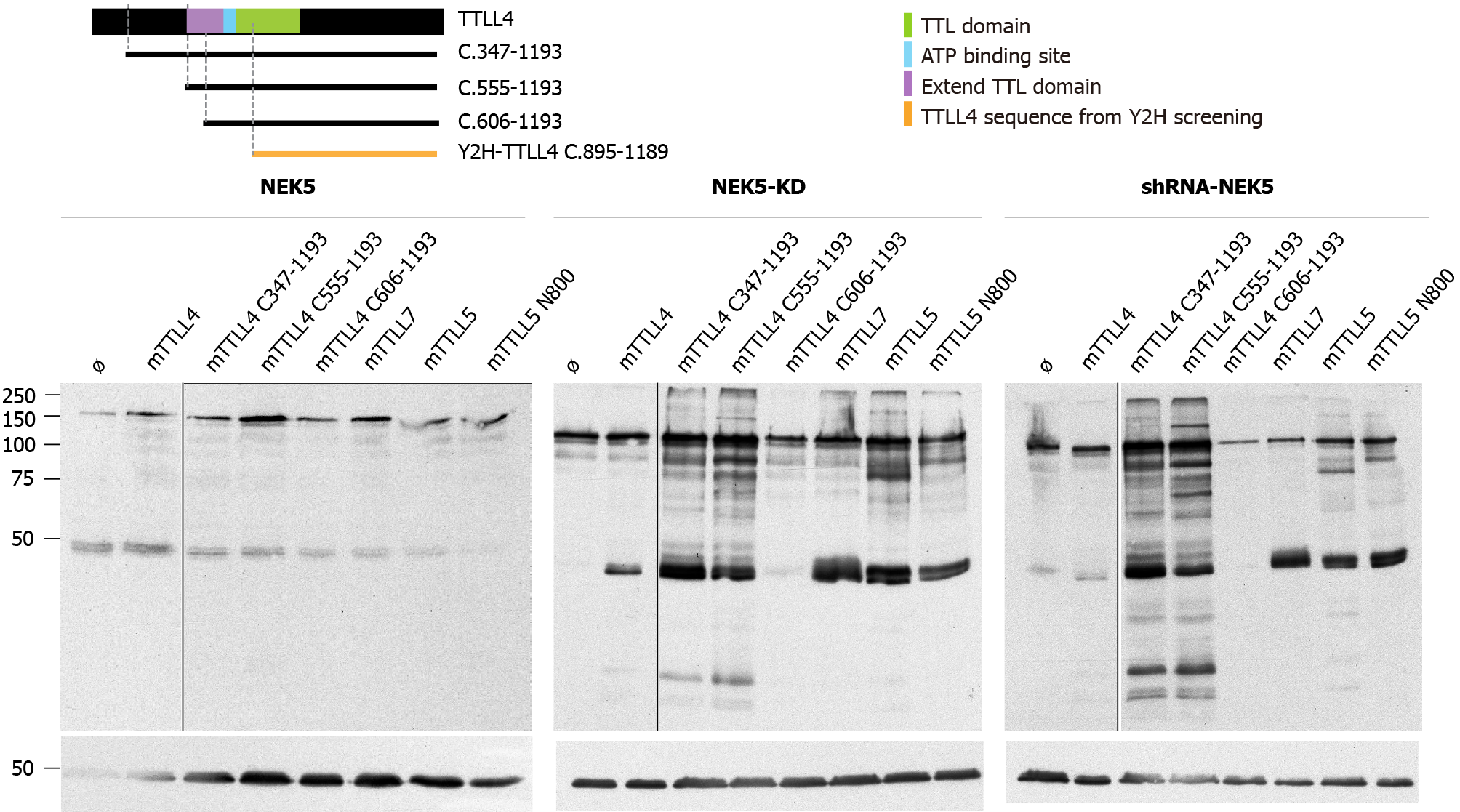

The putative catalytic region of TTLL4 is subdivided into two sub-domains: one common to all TTLLs and TTL, called “core TTL domain” (green region in Figure 3A) and a conserved bipartite upstream region called the “extended TTL domain” (purple and light blue regions in Figure 3A), which is necessary for TTLL4 activity[17].

The TTLL4 protein fragment found to interact with NEK5 in the yeast two-hybrid screen is localized in the C-terminal region between residues 895-1189. This suggests that the possible regulatory region of TTLL4 partially coincides with the catalytic TTL domain (a.a. 599-942). In order to map regions of TTLL4 required for its polygluta

Expression of the catalytically inactive NEK5 (Figure 3C) or the depletion of NEK5 expression (Figure 3D) resulted in an increased polyglutamylation activity for all TTLL4 truncated versions, except for the mutation C606-1193 (Figure 3C and D, lane 5), which is the inactive version, because it is missing the “extended domain” (Figure 3B-D, lane 5).

The overexpression of TTLL4 leads to the polyglutamylation of tubulin and many non-tubulin substrates in the presence of NEK5-KD and shRNA-NEK5. On the other hand, TTLL7, TTLL5 full size or its shortest version (TTLL5-N800) overexpression lead to more pronounced differences in polyglutamylation levels of tubulins (Figure 3C and D). The presence of NEK5 reduced the polyglutamylation of tubulins not only after TTLL4 transfection, but also TTLL7 and TTLL5, suggesting that the regulation by NEK5 may not be exclusive for TTLL4.

In order to confirm the regulatory role of NEK5 on the enzymatic activity of TTLL4 and TTLL5 toward tubulins, we performed an in vitro polyglutamylation assay. Purified tubulins from mouse brains were subjected to in vitro polyglutamylation assays with extracts from control and shRNA-NEK5 expressing cells, transiently transfected with EYFP-TTLL4 and EYFP-TTLL5. Once again the activity level of TTLL4 was increased in shRNA-NEK5-cell extract and reduced in the presence of NEK5 (Supplementary Figure 4). Inactive versions of TTLL4 and TTLL5 were used as a control in this experiment. Furthermore, NEK5 did not affect the activity level of TTLL5 using the in vitro assay (Supplementary Figure 4).

According to the Uniprot database, TTLL4 is phosphorylated on S691 and S696 residues and using the Kinase-specific Phosphorylation Site Prediction tool GPS 3.0[33] several other residues could also be phosphorylated. The amino acid residues with the highest score for phosphorylation were S1184, S1117, S1125 and S1151.

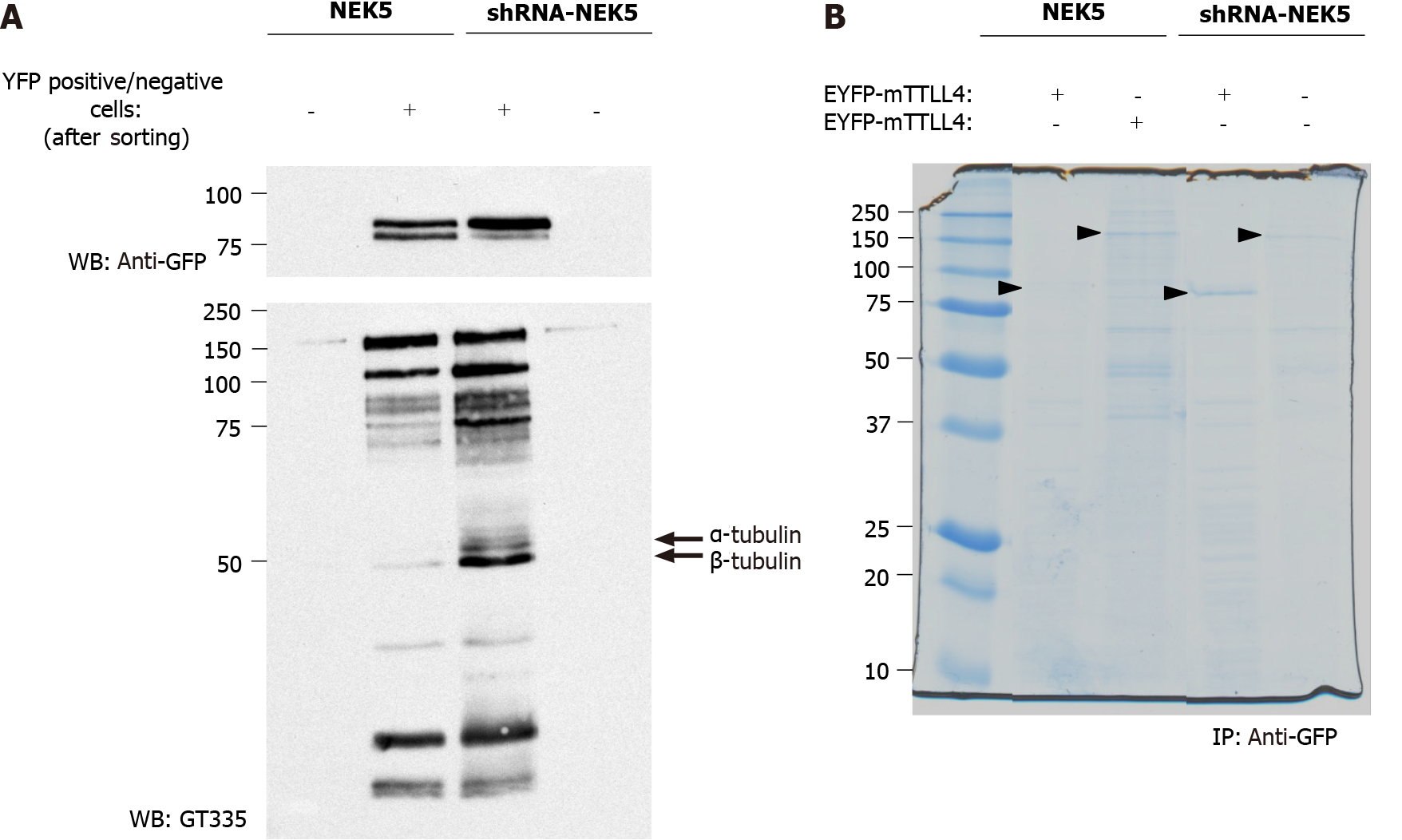

The prediction of TTLL4 phosphorylation sites associated with its inactivation in the presence of NEK5 suggests that NEK5 could phosphorylate TTLL4 directly or indirectly (through the phosphorylation/interaction with the effector kinase), thereby inhibiting its activity. To identify the possible phosphorylation sites in TTLL4 and TTLL5, stably NEK5-expressing cells and shRNA-NEK5 cells were transiently transfected with EYFP-TTLL4 or EYFP-TTLL5 (Figure 4A, only the TTLL4 experiment is shown). As the efficiency of the transfection is low, transfected cells were submitted to sorting by flow cytometry to enrich the cells expressing EYFP-TTLL4 or EYFP-TTLL5. The positive (TTLL4+ or TTLL5+) and negative (TTLL4- or TTLL5-) cells were collected in different tubes, lysed and the proteins separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for polyglutamylation levels by Western blot (Figure 4A).

TTLL4+ cells showed an increase in polyglutamylation levels, especially of tubulins, when NEK5 was depleted (Figure 4, compare lane 3 with lane 2). As expected, cells negative for YFP signal (TTLL4-) showed undetectable levels of polyglutamylation (Figure 4A, lanes 1 and 4). In the presence of NEK5, TTLL4, detected by the anti-GFP antibody, migrates as two bands, suggesting a phosphorylation event or another type of post-translational modification. The lower of those two bands is lost in cells in which NEK5 has been silenced (Figure 4A, upper panel, compare lanes 2 and 3). This could suggest the loss of phosphorylation of TTLL4 by NEK5.

In order to identify the phosphorylation sites in EYFP-TTLL4 and EYFP-TTLL5 proteins, the proteins of YFP positive cells were immunoprecipitated using anti-GFP beads and separated by SDS-PAGE (Figure 4B). The bands corresponding to the expected sizes of TTLL4 and TTLL5 (identified with the arrows in Figure 4B) were excised, submitted to trypsin and chymotrypsin digestion and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The analysis of the TTLL4 amino acid sequence allowed the identification of amino acid residues T813, S912, S960, T968, S1136 and S1139 as phos

To evaluate the polyglutamylation activity of phosphorylated TTLL4, the residues T813, S912, S960, T968 and S1139 of EYFP-TTLL4 were mutated to glutamic acid (E), mimicking phosphorylation. For inactivation of the phosphosites the residues T813, Y815, S960, S1136 and S1139 were mutated to alanine (A) or phenylalanine (F) for the residue Y815. The mutated residues, as well as their location in the full-length protein, are represented in Figure 5A. To investigate the in vivo enzyme activity of TTLL4 mutants, we expressed EYFP-tagged TTLL4 mutants in HEK293T cells and the levels of polyglutamylation were analyzed by Western blot using the GT335 antibody (Figure 5B).

The expression of unphosphorylated mutants TTLL4-Y815F, TTLL4-Y815A and TTLL4-S1136A in HEK293T cells caused an important decrease in the polyglutamy

Tubulin polyglutamylation has been suggested to regulate the interactions of some microtubule-associated proteins and molecular motors with microtubules, thus selectively controlling specific microtubule functions inside cells[32]. To control these complex modification patterns in time and space, strict control of the polyglu

Despite the importance of controlling polyglutamylation in cells, the regulatory mechanism that controls the activity of TTLL enzymes has not yet been identified. In this study we show that NEK5 interacts and has the potential to phosphorylate TTLL4, regulating its polyglutamylation activity. The expression of the enzymatically inactive version of NEK5 as well as shRNA-NEK5 cells showed increased levels of polyglu

NEK kinases have multiple biological functions but, until now, information regarding their substrates was scarce. Although they were first described as serine/threonine kinases, recent studies are classifying some members of the family as tyrosine-kinases as well[38]. The phosphorylation of TTLL4 at the tyrosine 815 site seems to control its activity and our data pointed to NEK5 as the potential effector kinase. Similar effects of enzyme inactivation by phosphorylation were observed for Protein-tyrosine Phosphatase 1B in response to insulin[39].

Our results indicate that the implications of NEKs in the regulation of TTLL enzymes could be of general importance for the control of tubulin glutamylation in cells. NEKs and TTLLs are often located or have functions in cilia, cytoplasmic microtubules or centrosomes. NEK kinases are extensively related to centrosomes and primary cilia[25,40-48]. Prosser et al[49] demonstrated that NEK5 is located at the centrosomes and is involved in ensuring its integrity during interphase and its separation during mitosis[49]. Centrosomes and basal bodies are highly polyglutamy

Strikingly, we found that interactions between NEK and TTLL family members are of a general nature, which implies that the NEK5 enzyme might be involved in regulation of the activity of different TTLL members. Thus, specific localization of the NEK kinases, together with locally-controlled interactions with TTLL is expected to control how and when a NEK kinase phosphorylates a TTLL enzyme.

Our work thus delivers a strong incentive to further explore the relationship between NEK kinases and members of the TTLL family. The centrosomal localization, the role of tubulin polyglutamylation in centrosome stability[7], associated with the fact that some kinases from different organisms are involved in centrosome maturation and integrity[51,52], all indicate that the relation between these two families need to be analyzed more profoundly especially in the cell cycle context, midbody formation and ciliary functions. Understanding the role of NEK kinases in the tubulin code will be essential in understanding the signaling networks controlling this complex regulatory mechanism.

In conclusion, our data suggest a mechanism for regulation of TTLL activity through phosphorylation by a member of the NEK family. shRNA knockdown of NEK5 or expression of a “KD” NEK5 in cells transfected with TTLL4 showed increased polyglutamylation levels, while HEK293T cells resulted in low polyglutamylation of proteins, especially tubulins. The regulation of TTLL4 occurs in the C-terminal region through the phosphorylation of its Y815 and S1136 residues and NEK5 emerged as the potential effector kinase.

Enzymes of the tubulin tyrosine ligase-like (TTLL) family are responsible for the polyglutamylation of tubulins and many other protein substrates. The never in mitosis gene A-related kinases (NEKs) are protein kinases involved in diverse aspects of regulation of the cell cycle, microtubules, primary cilia and the deoxyribonucleic acid damage response. Previous data from the literature and protein interaction data between TTLLs and NEKs suggested a possible crosstalk and regulatory connection between these two protein families.

In a yeast two-hybrid assay for protein interactors of human NEK5, TTLL4 was identified as a partner. Additionally, a previously report showed that purified extracts of NEK in Crithidia fasciculata was capable of glutamylating tubulins in vitro. Here, we set out to confirm the interaction between NEK5 and TTLL4 and to explore possible functional consequences of this interaction.

Confirm and map the interaction between TTLL4 and NEK5 proteins and explore a possible regulation mechanism of TTLL4 through phosphorylation.

We used transient transfection of full-length TTLL4, deletions and point mutants in cells with stable expression of NEK5 as well as knock down of NEK5 expression by short hairpin ribonucleic acid. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate a series of point mutants of TTLL4. The polyglutamylation activity of TTLL4 variants was assessed by Western blot, using antibody GT335, which detects polyglutamylation of protein substrates.

We confirmed the interaction between TTLL4 and NEK5 through yeast two hybrid screening and imunoprecipitation. Furthermore, we showed that expression of NEK5 interferes negatively in the polyglutamylation activity of TTLL4 towards tubulins and other protein substrates, whereas NEK5 knock down or over-expression of a kinase dead variant of NEK5 result in the contrary: An increase in TTLL4 activity. Mass spectrometry showed phosphorylation of TTLL4 on specific Thr, Ser and Tyr residues. Modification of some of these residues affected TTLL4 activity.

We describe, for the first time, the interaction between members of the NEK and TTLL families. A mechanism for regulation of TTLL4 activity through phosphorylation has emerged and NEK5 is a potential effector kinase, affecting polyglutamylation of many substrates.

This is the first evidence of a functional and regulatory crosstalk between TTLL and NEK protein families. Members of both families have localization and important functions at microtubules, primary cilia and centrosomes. The functional interplay of the protein families in the context of the cell cycle and microtubule functions should be explored in further detail. This work opens a new perspective of study on the NEK family, mainly in areas related to polyglutamylation, such as cilia, neuronal, blood and muscle disorders.

We would like to thanks Annemarie Wehenkel, Magiera MM and Janke C (Institut Curie, Orsay, France) for technical support, insightful suggestions and critical discussion of the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Biochemistry and molecular biology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Grawish M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Eddé B, Rossier J, Le Caer JP, Desbruyères E, Gros F, Denoulet P. Posttranslational glutamylation of alpha-tubulin. Science. 1990;247:83-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Redeker V, Levilliers N, Schmitter JM, Le Caer JP, Rossier J, Adoutte A, Bré MH. Polyglycylation of tubulin: a posttranslational modification in axonemal microtubules. Science. 1994;266:1688-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Piperno G, LeDizet M, Chang XJ. Microtubules containing acetylated alpha-tubulin in mammalian cells in culture. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:289-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Piras R, Piras MM. Changes in microtubule phosphorylation during cell cycle of HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1975;72:1161-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rodriguez JA, Borisy GG. Tyrosination state of free tubulin subunits and tubulin disassembled from microtubules of rat brain tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;89:893-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lechtreck KF, Geimer S. Distribution of polyglutamylated tubulin in the flagellar apparatus of green flagellates. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2000;47:219-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bobinnec Y, Khodjakov A, Mir LM, Rieder CL, Eddé B, Bornens M. Centriole disassembly in vivo and its effect on centrosome structure and function in vertebrate cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1575-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Regnard C, Desbruyères E, Denoulet P, Eddé B. Tubulin polyglutamylase: isozymic variants and regulation during the cell cycle in HeLa cells. J Cell Sci. 1999;112 (Pt 23):4281-4289. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Verhey KJ, Gaertig J. The tubulin code. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2152-2160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Janke C. The tubulin code: molecular components, readout mechanisms, and functions. J Cell Biol. 2014;206:461-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boucher D, Larcher JC, Gros F, Denoulet P. Polyglutamylation of tubulin as a progressive regulator of in vitro interactions between the microtubule-associated protein Tau and tubulin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12471-12477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Backer CB, Gutzman JH, Pearson CG, Cheeseman IM. CSAP localizes to polyglutamylated microtubules and promotes proper cilia function and zebrafish development. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2122-2130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bonnet C, Boucher D, Lazereg S, Pedrotti B, Islam K, Denoulet P, Larcher JC. Differential binding regulation of microtubule-associated proteins MAP1A, MAP1B, and MAP2 by tubulin polyglutamylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12839-12848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Larcher JC, Boucher D, Lazereg S, Gros F, Denoulet P. Interaction of kinesin motor domains with alpha- and beta-tubulin subunits at a tau-independent binding site. Regulation by polyglutamylation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22117-22124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sirajuddin M, Rice LM, Vale RD. Regulation of microtubule motors by tubulin isotypes and post-translational modifications. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:335-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Janke C, Rogowski K, Wloga D, Regnard C, Kajava AV, Strub JM, Temurak N, van Dijk J, Boucher D, van Dorsselaer A, Suryavanshi S, Gaertig J, Eddé B. Tubulin polyglutamylase enzymes are members of the TTL domain protein family. Science. 2005;308:1758-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van Dijk J, Rogowski K, Miro J, Lacroix B, Eddé B, Janke C. A targeted multienzyme mechanism for selective microtubule polyglutamylation. Mol Cell. 2007;26:437-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Goettler D, Rao AV, Bird RP. The effects of a “low-risk” diet on cell proliferation and enzymatic parameters of preneoplastic rat colon. Nutr Cancer. 1987;10:149-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ersfeld K, Wehland J, Plessmann U, Dodemont H, Gerke V, Weber K. Characterization of the tubulin-tyrosine ligase. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:725-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Regnard C, Desbruyères E, Huet JC, Beauvallet C, Pernollet JC, Eddé B. Polyglutamylation of nucleosome assembly proteins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15969-15976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | van Dijk J, Miro J, Strub JM, Lacroix B, van Dorsselaer A, Edde B, Janke C. Polyglutamylation is a post-translational modification with a broad range of substrates. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3915-3922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | O’Connell MJ, Krien MJ, Hunter T. Never say never. The NIMA-related protein kinases in mitotic control. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | O’regan L, Blot J, Fry AM. Mitotic regulation by NIMA-related kinases. Cell Div. 2007;2:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Belham C, Roig J, Caldwell JA, Aoyama Y, Kemp BE, Comb M, Avruch J. A mitotic cascade of NIMA family kinases. Nercc1/Nek9 activates the Nek6 and Nek7 kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34897-34909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Meirelles GV, Perez AM, de Souza EE, Basei FL, Papa PF, Melo Hanchuk TD, Cardoso VB, Kobarg J. “Stop Ne(c)king around”: How interactomics contributes to functionally characterize Nek family kinases. World J Biol Chem. 2014;5:141-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Westermann S, Weber K. Identification of CfNek, a novel member of the NIMA family of cell cycle regulators, as a polypeptide copurifying with tubulin polyglutamylation activity in Crithidia. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:5003-5012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Melo Hanchuk TD, Papa PF, La Guardia PG, Vercesi AE, Kobarg J. Nek5 interacts with mitochondrial proteins and interferes negatively in mitochondrial mediated cell death and respiration. Cell Signal. 2015;27:1168-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8015] [Cited by in RCA: 40252] [Article Influence: 821.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wolff A, de Néchaud B, Chillet D, Mazarguil H, Desbruyères E, Audebert S, Eddé B, Gros F, Denoulet P. Distribution of glutamylated alpha and beta-tubulin in mouse tissues using a specific monoclonal antibody, GT335. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;59:425-432. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Chien CT, Bartel PL, Sternglanz R, Fields S. The two-hybrid system: a method to identify and clone genes for proteins that interact with a protein of interest. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:9578-9582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 995] [Cited by in RCA: 1104] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4257] [Cited by in RCA: 4329] [Article Influence: 120.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Janke C, Bulinski JC. Post-translational regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton: mechanisms and functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:773-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Xue Y, Liu Z, Cao J, Ma Q, Gao X, Wang Q, Jin C, Zhou Y, Wen L, Ren J. GPS 2.1: enhanced prediction of kinase-specific phosphorylation sites with an algorithm of motif length selection. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2011;24:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kubo T, Yanagisawa HA, Yagi T, Hirono M, Kamiya R. Tubulin polyglutamylation regulates axonemal motility by modulating activities of inner-arm dyneins. Curr Biol. 2010;20:441-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Suryavanshi S, Eddé B, Fox LA, Guerrero S, Hard R, Hennessey T, Kabi A, Malison D, Pennock D, Sale WS, Wloga D, Gaertig J. Tubulin glutamylation regulates ciliary motility by altering inner dynein arm activity. Curr Biol. 2010;20:435-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pathak N, Obara T, Mangos S, Liu Y, Drummond IA. The zebrafish fleer gene encodes an essential regulator of cilia tubulin polyglutamylation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4353-4364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Rogowski K, van Dijk J, Magiera MM, Bosc C, Deloulme JC, Bosson A, Peris L, Gold ND, Lacroix B, Bosch Grau M, Bec N, Larroque C, Desagher S, Holzer M, Andrieux A, Moutin MJ, Janke C. A family of protein-deglutamylating enzymes associated with neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;143:564-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | van de Kooij B, Creixell P, van Vlimmeren A, Joughin BA, Miller CJ, Haider N, Simpson CD, Linding R, Stambolic V, Turk BE, Yaffe MB. Comprehensive substrate specificity profiling of the human Nek kinome reveals unexpected signaling outputs. Elife. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Tao J, Malbon CC, Wang HY. Insulin stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation and inactivation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29520-29525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Habbig S, Bartram MP, Sägmüller JG, Griessmann A, Franke M, Müller RU, Schwarz R, Hoehne M, Bergmann C, Tessmer C, Reinhardt HC, Burst V, Benzing T, Schermer B. The ciliopathy disease protein NPHP9 promotes nuclear delivery and activation of the oncogenic transcriptional regulator TAZ. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5528-5538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hilton LK, White MC, Quarmby LM. The NIMA-related kinase NEK1 cycles through the nucleus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389:52-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kim S, Kim S, Rhee K. NEK7 is essential for centriole duplication and centrosomal accumulation of pericentriolar material proteins in interphase cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3760-3770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Lee MY, Moreno CS, Saavedra HI. E2F activators signal and maintain centrosome amplification in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:2581-2599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mahjoub MR, Trapp ML, Quarmby LM. NIMA-related kinases defective in murine models of polycystic kidney diseases localize to primary cilia and centrosomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3485-3489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Patil M, Pabla N, Ding HF, Dong Z. Nek1 interacts with Ku80 to assist chromatin loading of replication factors and S-phase progression. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:2608-2616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sdelci S, Bertran MT, Roig J. Nek9, Nek6, Nek7 and the separation of centrosomes. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3816-3817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sdelci S, Schütz M, Pinyol R, Bertran MT, Regué L, Caelles C, Vernos I, Roig J. Nek9 phosphorylation of NEDD1/GCP-WD contributes to Plk1 control of γ-tubulin recruitment to the mitotic centrosome. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1516-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zalli D, Bayliss R, Fry AM. The Nek8 protein kinase, mutated in the human cystic kidney disease nephronophthisis, is both activated and degraded during ciliogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1155-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Prosser SL, Sahota NK, Pelletier L, Morrison CG, Fry AM. Nek5 promotes centrosome integrity in interphase and loss of centrosome cohesion in mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2015;209:339-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Geimer S, Teltenkötter A, Plessmann U, Weber K, Lechtreck KF. Purification and characterization of basal apparatuses from a flagellate green alga. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;37:72-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Fry AM, Mayor T, Meraldi P, Stierhof YD, Tanaka K, Nigg EA. C-Nap1, a novel centrosomal coiled-coil protein and candidate substrate of the cell cycle-regulated protein kinase Nek2. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1563-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Uto K, Nakajo N, Sagata N. Two structural variants of Nek2 kinase, termed Nek2A and Nek2B, are differentially expressed in Xenopus tissues and development. Dev Biol. 1999;208:456-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |