Published online Mar 27, 2017. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i3.82

Peer-review started: August 27, 2016

First decision: September 27, 2016

Revised: December 28, 2016

Accepted: January 16, 2017

Article in press: January 18, 2017

Published online: March 27, 2017

Processing time: 209 Days and 15.9 Hours

To benchmark severity of complications using the Accordion Severity Grading System (ASGS) in patients undergoing operation for severe pancreatic injuries.

A prospective institutional database of 461 patients with pancreatic injuries treated from 1990 to 2015 was reviewed. One hundred and thirty patients with AAST grade 3, 4 or 5 pancreatic injuries underwent resection (pancreatoduodenectomy, n = 20, distal pancreatectomy, n = 110), including 30 who had an initial damage control laparotomy (DCL) and later definitive surgery. AAST injury grades, type of pancreatic resection, need for DCL and incidence and ASGS severity of complications were assessed. Uni- and multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied.

Overall 238 complications occurred in 95 (73%) patients of which 73% were ASGS grades 3-6. Nineteen patients (14.6%) died. Patients more likely to have complications after pancreatic resection were older, had a revised trauma score (RTS) < 7.8, were shocked on admission, had grade 5 injuries of the head and neck of the pancreas with associated vascular and duodenal injuries, required a DCL, received a larger blood transfusion, had a pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) and repeat laparotomies. Applying univariate logistic regression analysis, mechanism of injury, RTS < 7.8, shock on admission, DCL, increasing AAST grade and type of pancreatic resection were significant variables for complications. Multivariate logistic regression analysis however showed that only age and type of pancreatic resection (PD) were significant.

This ASGS-based study benchmarked postoperative morbidity after pancreatic resection for trauma. The detailed outcome analysis provided may serve as a reference for future institutional comparisons.

Core tip: Pancreatic injuries result in considerable morbidity and mortality rates if the injury is inadequately treated. This analysis benchmarked the severity of complications after pancreatic resection for trauma using the Accordion Severity Grading System. By applying univariate logistic regression analysis, the mechanism of injury, a revised trauma score < 7.8, shock on admission to hospital, the need for an initial damage control laparotomy, an increasing pancreatic injury grade and the type of pancreatic resection were found to be significant variables for complications. However, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that only age and the type of pancreatic resection were significant. Post-operative morbidity after pancreatic resection for trauma in this study was substantial and an increasing complication severity grade, as measured by the Accordion severity scale, required escalation of intervention and prolonged hospitalisation.

- Citation: Krige JE, Jonas E, Thomson SR, Kotze UK, Setshedi M, Navsaria PH, Nicol AJ. Resection of complex pancreatic injuries: Benchmarking postoperative complications using the Accordion classification. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 9(3): 82-91

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v9/i3/82.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v9.i3.82

Major pancreatic resections are technically complex procedures, especially so when performed as an emergency in severely injured patients who also have multiple other injuries[1,2]. There are wide-ranging disparities in the reported overall postoperative morbidity rates after pancreatic injuries due to non-standardised analyses and a lack of comprehensive datasets which specifically document outcome after resection of complex pancreatic injuries[3-5]. The absence of an appropriate and defined methodology to measure and register peri-operative outcome, precludes the generation of validated outcome data, fundamental to accurate benchmarking of surgical performance and internal quality control[6]. Both the number and severity of postoperative complications are recognised key short-term surrogate markers of the quality of operative intervention and surgical outcome[7].

The development and application of internationally accepted and validated International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definitions of complications in elective pancreatic surgery has provided accurate, robust and consistent data which has allowed reliable comparisons of, for example, the incidence of post-operative pancreatic fistulas[8], bleeding[9] and delayed gastric emptying (DGE)[10]. Similarly, the 6-scale Accordion Severity Grading System (ASGS) which discriminates post-operative complication severity following elective surgery on the basis of escalating interventional criteria, is now widely accepted as a credible, scoring system which is easy to apply and is reproducible with minimal inter-observer variability[11].

Earlier studies assessing outcome after pancreatic resections for major pancreatic injuries have applied unqualified primary endpoints with differing descriptions and definitions which consequently have resulted in flawed conclusions. Our group has previously evaluated other aspects of pancreatic trauma and, as one of the world’s busiest high volume academic trauma centers, has sufficient prospective granular data available to investigate organ-specific research questions[12-15]. The aim of this research project was to provide a detailed analysis to benchmark the severity of complications after pancreatic resection for severe trauma in a civilian patient population using the ASGS.

Groote Schuur Hospital is a high-volume, integrated academic referral centre serving a population of 3 million people with an annual operative trauma volume averaging 13000 patients. All HPB trauma is managed in the Level 1 Trauma Centre in conjunction with the Hepatopancreatobiliary and Surgical Gastroenterology units. A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data derived from a comprehensive and dedicated institutional pancreatic trauma database which includes clinical, operative and postoperative information on all patients treated for pancreatic trauma was performed of all adult patients who had a resection for a pancreatic injury between January 1990 and April 2015. Current guidelines of good clinical practice were followed and data collection and analysis were approved by the departmental, institutional and university research and ethics review boards. A statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

The medical records including operative, intensive care, radiology and endoscopy reports were reviewed and data abstracted were entered by a specially trained nurse reviewer and recorded using a standardised data form after affirmation by a senior study surgeon. Details of the methodology used to record the variables for each patient have previously been published[12-17]. A comprehensive data set of complications and related key variables were recorded.

Postoperative complications were scored using the expanded ASGS[11] (Table 1). In this study grade 1 and 2 complications were regarded as minor, grade 3 as moderate, 4 as serious and grade 5 complications as life-threatening. Grade 6 complications resulted in the death of the patient and included death from any cause within 30 d of surgery. The overall complication rate was reported as the number of patients with at least one complication. In patients with several complications, the highest graded complication was used for analysis of the complication severity.

| Expanded Accordion Classification (levels of severity) | |

| Mild | Requires only minor invasive procedures that can be done at the bedside physiotherapy and the following drugs are allowed: Antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics and electrolytes |

| Moderate | Requires pharmacologic treatment with drugs other than such allowed for minor complications, for instance antibiotics |

| Blood transfusions and total parenteral nutrition are also included | |

| Severe | Invasive procedure/no GA, requires management by an endoscopic, interventional procedure or re-operation without general anesthesia |

| Severe | Invasive procedure under GA or single organ system failure requires management by an operation under general anesthesia or results in single organ system failure |

| Severe | Organ system failure and invasive procedure under GA or multisystem organ failure, such complications would normally be managed in an increased acuity setting but in some cases patients with complications of lower severity might also be admitted to an ICU |

| Deaths | Postoperative death |

Shock was defined as a systolic blood pressure less < 90 mm Hg pre- or intra-operatively. Pancreatic injury grade[18], pancreatic fistula[8], organ dysfunction[19], infectious complications and septic shock[20] were defined and graded according to internationally consensus guidelines.

Initial resuscitation was implemented using Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines. Emergency surgery was undertaken in patients who had an acute abdomen with clinical signs of peritonitis or evidence of major intra-abdominal bleeding. From 1995 onwards hemodynamically unstable patients who had major associated organ and visceral vascular injuries had an initial damage control laparotomy (DCL) before later definitive intervention[21]. Patients in whom imaging revealed the need for intervention or had a high clinical suspicion of a major pancreatic injury underwent urgent exploration.

Operative management of the pancreatic injury was based on our institutional trauma protocol, based on the hemodynamic stability of the patient, the magnitude and extent of associated injuries and the location and severity of the pancreatic injury[12,22]. In brief, major lacerations of the body or tail of the pancreas with likely duct injury were treated by distal pancreatectomy. Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) was restricted to patients with non-salvageable injuries who had disruption of the ampulla of Vater or major devitalising injuries of the pancreatic head and duodenum and was done as a primary procedure during the initial operation if the patient was stable or as a secondary staged procedure after the DCL. A pylorus-preserving PD was the preferred pancreatic head resection[16]. All pancreatic resections were drained intra-operatively.

DCL was applied in critically injured patients with severe metabolic acidosis as indicated by a pH < 7.2, hypothermia with a core temperature < 35 °C or coagulopathy[21]. This involved an abbreviated laparotomy for rapid control of intra-abdominal bleeding, closure of visceral perforations and temporary abdominal wall closure. Patients were transferred to an intensive care unit for invasive monitoring, cardiopulmonary support and urgent volume replacement to correct acidosis, coagulopathy and hypothermia and restore normal physiology[23].

Postoperative intra-abdominal collections were drained percutaneously using ultrasound- or CT-guided catheter placement. Endoscopic therapy techniques were used to treat persistent pancreatic and duodenal fistulas and pancreatic fluid collections[24,25].

The data were analysed using Stata version 11 (Stata Corp. 2009. Stata: Release 11. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). For bivariate analysis the Pearson chi-square or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for categorical variables, and the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test for numerical variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals of clinical variables (while excluding collinearity). All statistical tests were two-tailed and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between January 1990 and April 2015 a total of 461 patients were treated for pancreatic injuries of whom 130 had a pancreatic resection for either grade 3, 4 or 5 injuries. Most patients were men and 74% had sustained penetrating injuries, predominantly gunshot wounds (GSW) (Table 2). One third of patients were shocked on admission and 30 patients (23.1%) had an emergency operation.

| Total (n = 130) | Those with complications (n = 95) | Those without complications (n = 35) | P-value | |

| Age (yr), median (range) | 26 (13-73) | 28 (13-73) | 24 (15-59) | 0.0064a |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| GSW | 88 (67.7%) | 63 (66.3%) | 25 (71.43%) | 0.6490c |

| Stab | 7 (5.4%) | 6 (6.3%) | 1 (2.86%) | |

| Blunt | 35 (26.9%) | 26 (27.3%) | 9 (25.71%) | |

| Hospital stay, median (range) | 8 (1-255) | 23 (1-255) | 9 (5-58) | 0.0000a |

| ICU stay | 77 (59.23%) | 68 (71.58%) | 9 (25.71%) | 0.0000b |

| Number ICU days, median (range) | 3 (0-153) | 4 (0-153) | 3 (0-7) | 0.0000a |

| RTS | ||||

| < 7.8 | 49 (37.69%) | 44 (46.32%) | 5 (14.29%) | 0.001b |

| 7.8 | 81 (62.3%) | 51 (53.68%) | 30 (85.71%) | |

| Patients shocked on admission (n, %) | 46 (35.4%) | 42 (44.21%) | 4 (11.43%) | 0.001b |

| Patients who received a blood transfusion (n, %) | 103 (79.2%) | 79 (83.16%) | 24 (68.57%) | 0.069b |

| Units of blood transfused, median units (range) | 84.5 (0-124a) | 8 (0-124) | 2 (0-28) | 0.0000a |

| Damage control surgery | 30 (23.1%) | 27 (28.42%) | 3 (8.57%) | 0.0176b |

| Pancreatic injury site | ||||

| Head and neck of pancreas | 24 (18.5%) | 20 (21.05%) | 4 (11.43%) | 0.0443c |

| Body of pancreas | 57 (43.8%) | 44 (46.32%) | 13 (37.14%) | |

| Tail of pancreas | 49 (37.7%) | 31(32.63%) | 18 (51.43%) | |

| AAST | ||||

| Grade 3 | 107 (82.3%) | 74 (77.89%) | 33 (94.28%) | 0.0297c |

| Grade 4 | 4 (3.1%) | 3 (3.16%) | 1 (2.86%) | |

| Grade 5 | 19 (14.6%) | 18 (18.95%) | 1 (2.86%) | |

| Associated abdominal injuries | ||||

| Nil (isolated injury) | 14 (10.8%) | 10 (10.53%) | 4 (11.43%) | 0.8833c |

| 1 or 2 organs injured | 51 (39.2%) | 37 (38.95%) | 14 (40%) | |

| 3 or more injured | 65 (50%) | 48 (50.53%) | 17 (48.57%) | |

| Associated injured organs | ||||

| Liver | 53 (40.7%) | 40 (42.11%) | 13 (37.14%) | 0.6109 |

| Kidney | 53 (40.7%) | 34 (35.79%) | 19 (54.29%) | 0.0579 |

| Spleen | 52 (40%) | 39 (41.05%) | 13 (37.14%) | 0.6876 |

| Stomach | 49 (37.7%) | 32 (33.68%) | 17 (48.57%) | 0.1217 |

| Diaphragm | 38 (29.2%) | 28 (29.47%) | 10 (28.57%) | 0.9204 |

| Colon | 32 (24.6%) | 27 (28.42%) | 5 (14.29%) | 0.0983 |

| Duodenum | 22 (16.9%) | 20 (21.05%) | 2 (5.71%) | 0.0393a |

| Pancreatic resection type | ||||

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 20 (15.4%) | 19 (20%) | 1 (2.86%) | 0.0004c |

| Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy | 95 (73%) | 70 (73.68%) | 25 (71.4%) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy with spleen preservation | 15 (11.5%) | 6 (6.32%) | 9 (25.7%) | |

| Associated vascular injuries | 24 (18.5%) | 24 (25.26%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001b |

| Patients who had a repeat laparotomy (n, %) | 58 (44.6%) | 55 (57.89%) | 3 (8.57%) | 0.0000b |

| No. of repeat laparotomies done, median (range) | 0 (1-10) | 1 (0-10) | 0 (0-1) | 0.0000a |

| Death | 19 (14.62%) | 19 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0.004b |

One-fifth of patients had pancreatic head or neck injuries and four-fifths had injuries involving either the pancreatic body or tail. More than 80% sustained AAST grade 3 injuries and 18% had grade 4 or grade 5 injuries (Table 2).

Fifty-two patients (40%) had 77 extra-abdominal injuries of whom 65 (50%) had three or more associated adjacent organ injuries, predominantly involving the liver and spleen. Fourteen patients had an isolated pancreatic injury. Twenty-four patients (18%) had associated vascular injuries, of whom 15 had an IVC injury. The presence of an associated vascular injury correlated significantly (P = 0.007) with shock at presentation.

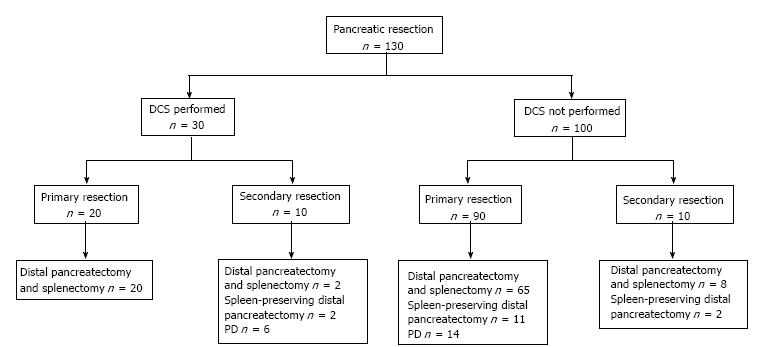

The 130 patients underwent a total of 287 laparotomies. Their surgical therapy is detailed in Figure 1. Thirty of the 130 patients (23%) had an initial DCL. Twenty patients had a PD, 14 of which were completed during the index laparotomy and 6 at a second laparotomy. Thirteen patients underwent a pylorus-preserving PD, and 7 had a conventional PD. Fifty-eight patients (44.6%) had a repeat laparotomy (range 1-10), 25 following an initial DCL, 16 for intra-abdominal infection unresolved by percutaneous catheter drainage, 10 for control of intra-abdominal bleeding and 7 for small bowel obstruction. Ninety five patients (73.1%) had a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy, and 15 (11.5%) had a spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy.

Of the 130 patients who had a pancreatic resection, 35 made an uneventful recovery without any postoperative complications. A total of 238 complications occurred in the remaining 95 patients. The severity of postoperative complications as classified using the ASGS is summarized in Table 3. Twenty-nine events were related to bleeding (intra-abdominal bleeding: n = 11, DIC: n = 18), 52 patients had respiratory related complications (21.8% of all events) and 20 had renal complications (8.4% of all events). Systemic sepsis occurred in 19 patients, intra-abdominal infections in 42 and wound infection in nine. Overall complications occurred in 95% of patients who had a PD compared to 69% who had a distal pancreatectomy (P = 0.0004).

| Accordion Severity Grade | Mild | Moderate | Severe: Invasive/no GA | Severe: Invasive/GA | Severe: Organ failure | Death | Total |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | n = 130 | |

| Surgical complications | |||||||

| Pancreatic | |||||||

| Fistula | 1 | 11 | 6 | 6a | -- | -- | 24 (18.5%) |

| Peri-pancreatic collection | -- | 3 | 4 | 1 | -- | -- | 8 (6.6%) |

| Pseudocyst | -- | -- | 1 | 1 | -- | -- | 2 (1.5%) |

| Pancreatic necrosis | 2 | 2 (1.5%) | |||||

| Intra-abdominal | |||||||

| Postoperative ileus | 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2 (1.5%) |

| Intra-abdominal infection | -- | 9 | 17 | 16 | -- | -- | 42 (32.3%) |

| Biliary fistula | -- | 1 | -- | 1 | -- | -- | 2 (1.5%) |

| Small bowel obstruction | -- | 1 | -- | 7 | -- | -- | 8 (6.6%) |

| Enterocutaneous fistula | -- | 9 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 9 (6.9%) |

| Anastomotic leak | -- | -- | -- | 3 | -- | -- | 3 (2.3%) |

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | -- | -- | -- | 3 | -- | -- | 3 (2.3%) |

| Wound | |||||||

| Wound infection | -- | 7 | -- | 2b | -- | -- | 9 (6.9%) |

| Wound dehiscence | -- | 1 | -- | 1 | -- | -- | 2 (1.5%) |

| Bleeding | |||||||

| Intra-abdominal | -- | 4 | -- | 6 | -- | 1 | 11 (8.5%) |

| DIC | -- | 7 | -- | -- | 6 | 5 | 18 (13.8%) |

| Non-surgical complications | |||||||

| Respiratory | |||||||

| Pleural effusion | 9 | 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 11 (8.5%) |

| Atelectasis | 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Pneumonia | -- | 14 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 14 (10.7%) |

| Respiratory failure | -- | -- | -- | 10 | 6 | 9 | 25 (19.2%) |

| Renal | |||||||

| Renal failure | -- | -- | -- | 8 | 10 | 1 | 19 (14.6%) |

| Intra-abdominal urine leak | -- | -- | -- | 1 | -- | -- | 1 (0.8%) |

| Systemic sepsis | -- | 12 | -- | -- | 4 | 3 | 19 (14.6%) |

| Other | 1c | 1d | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2 (1.5%) |

| Total | 15 (6.3%) | 82 (34.5%) | 28 (11.8%) | 68 (28.6%) | 26 (10.9%) | 19 (8.0%) | 238 |

Thirty-three patients had a total of 36 pancreatic complications following pancreatic resection (Table 4). Twenty-four patients developed a pancreatic fistula, 15 of which resolved on conservative management alone. Nine patients with persistent fistulae had ERCP with sphincterotomy and pancreatic duct stenting (n = 7) or pancreatic duct sphincterotomy only (n = 2). Two patients developed symptomatic pseudocysts which were treated with endoscopic ultrasound-guided transgastric stent drainage. Eight patients had peri-pancreatic fluid collections of which seven were successfully drained percutaneously. One patient with a complex pancreato-colo-cutaneous fistula underwent a left hemicolectomy. Three of 20 patients (15%) developed a pancreatic fistula after PD compared to 21 of 110 (19%) after a distal pancreatectomy (Table 4).

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 20) | Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (n = 95) | Distal pancreatectomy with spleen preservation (n = 15) | P-value1 | |

| No. of patients with any complication | 19 (95%) | 70 (73.7%) | 6 (40%) | 0.0014 |

| Complications non-surgical | 15 (75%) | 58 (61.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.0006 |

| Complications surgical (Other) | 12 (60%) | 37 (38.9%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0.1111 |

| Complications pancreatic | 3 (15%) | 25 (26.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 0.4339 |

| Days in hospital, median (range) | 22 (3-94) | 17 (1-255) | 15 (5-58) | 0.1797 |

| ICU admissions | 19 (95%) | 55 (57.9%) | 3 (20%) | 0.0001 |

| Days in ICU, median (range) | 4 (1-20) | 7 (1-153) | 7, 9, 16 respectively | 0.0099 |

| Outcome died | 4 (20%) | 14 (14.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0.5445 |

Duration of hospital stay was analysed for the different ASGS grades. In patients with more than one complication the highest grade was used. Those with no post-operative complications (grade 0, n = 35) had a median 9 (range: 5-58) day post-resection hospital stay. Grade 1 patients (n = 3) spent 14, 23 and 34 d in hospital, grade 2 (n = 14, median 22, range 6-94 d), grade 3 (n = 17, median 24, range: 9-58 d), grade 4 (n = 40, median 33, range: 7-255 d), grade 5 (n = 2, 9 and 19 d) and grade 6 (n = 19, median 14, range: 1-52).

Nineteen patients (14.6%) died post-operatively (GSW 15, blunt 3, stab 1) of whom 13 were shocked on admission, 10 had major vascular injuries, 11 had 3 or more associated abdominal organ injuries required a median of 25 units of blood (range 4-89). Five deaths occurred within the first 24 h as a result of complications related to bleeding, DIC and shock due to a combination of complex peri-pancreatic visceral vascular injuries. Fourteen patients died after 24 h (median 17 d, range 2-52 d) of multi-organ failure (MOF), respiratory failure (n = 9), DIC (n = =5), septic shock (n = 3), renal failure (n = 1) and abdominal bleeding (n = 1). Four patients (20%) died after PD, including two of the six patients who underwent a delayed PD and reconstruction after DCL (Table 4).

Patients who were older, those who had a RTS ≥ 7.8, were shocked on admission, had grade 5 injuries with associated vascular or duodenal injuries, required a DCL, received a larger blood transfusion, had a PD or repeat laparotomies were more likely to have complications after pancreatic resection (Table 2). Applying univariate logistic regression analysis mechanism of injury, RTS ≥ 7.8, shock on admission, DCL, greater AAST grade and type of pancreatic resection (PD) were significant variables for complications (Table 5). Multivariate logistic regression analysis, however showed only age and type of pancreatic resection (PD) to be significant (Table 5).

| Risk factor | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | ||||

| Odds ratio | 95%CI | P-value | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Age median, range | 0.9 | 0.58-1.43 | 0.699 | 0.9 | 0.82-0.99 | 0.031 |

| Mechanism of injury | 0.9 | 0.89-0.98 | 0.017 | 0.4 | 0.12-1.39 | 0.155 |

| RTS (< 7.8) | 5.1 | 1.85-14.5 | 0.002 | 10.8 | 0.15-788 | 0.277 |

| No. of patients shocked on admission | 6.1 | 2.0-18.8 | 0.001 | 0.5 | 0.00-30.2 | 0.728 |

| No. of patients who received a blood transfusion | 2.3 | 0.93-5.53 | 0.073 | 0.5 | 0.00-3.64 | 0.486 |

| Damage control surgery | 1.6 | 1.18-2.2 | 0.030 | 1.36 | 0.68-2.69 | 0.373 |

| Pancreatic injury site | 1.8 | 0.99-3.15 | 0.050 | 2.4 | 0.57-100 | 0.231 |

| AAST | 0.5 | 0.23-0.92 | 0.028 | 3.8 | 0.67-21.9 | 0.131 |

| Pancreatic resection type | 4.8 | 1.91-12.0 | 0.001 | 65.7 | 3.13-1381 | 0.007 |

| Associated abdominal injuries | 1.1 | 0.32-3.7 | 0.883 | 12.9 | 0.39-423 | 0.152 |

The present study is the largest series to date of consecutive patients undergoing a major pancreatic resection for trauma and represents a select cohort of severe pancreatic injuries with the common denominator a main pancreatic duct injury. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine ASGS metrics to assess the usefulness of the scoring system to benchmark the spectrum and severity of complications after pancreatic resection for trauma. Unlike the planning and precision of elective pancreatic resections performed under controlled conditions with prior knowledge of co-morbidities, extent of pathology and anatomical considerations, the complexities and unpredictable operative demands surgeons are faced with during a pancreatic resection for trauma frequently require flexible or innovative strategies[22]. There seldom is the opportunity to evaluate and study the details of the injury pre-operatively and resection is often undertaken under unfavourable circumstances when other competing life-threatening injuries are present and take precedence[16].

The accurate intra-operative assessment of major pancreatic injuries may be complex and the surgeon may be faced with a range of uncertainties, some of which only become apparent during the procedure[16,17,22]. When major blood loss and shock occur, strategies including rapid haemostasis and damage control intervention become imperative, necessitating deferred resection and/or reconstruction at a more opportune time when abnormal physiological parameters have been restored[17,26]. After resection, technical difficulties may arise in the reconstruction of the pancreatic and biliary anastomoses due to a mismatch in size with non-dilated biliary and pancreatic ducts, often aggravated by gross edema of the jejunum and small bowel mesentery and soft pancreatic parenchyma[12,16]. Although 20 patients in our study had a PD for grade 5 injuries, a procedure of this magnitude is seldom necessary and should only be undertaken in stable patients when lesser operations are not feasible[16]. Although pancreas-specific complications were surprisingly low after PD, the overall complication rate in this category of resection was high. This emphasizes the need for combined and integrated involvement of both trauma and HPB surgeons familiar with the full spectrum and exigencies of pancreatic trauma[17].

The salient features of this study are the high proportion of patients who required a pancreatic resection for major injuries and the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with it. Major injuries to the pancreas remain a significant source of morbidity even when treated in well-resourced high-volume specialist trauma referral centers[21,22,27]. Outcome is influenced by the mechanism, anatomical location, grade and complexity of the pancreatic injury, the amount of blood lost, duration of hypovolemic shock, the quality of resuscitation, number of associated injuries and the appropriateness and quality of surgical intervention[3,15,27,28]. Overall reported morbidity rates following pancreatic injury range from 30% to 70% with the higher reported percentages generally being the result of severe trauma with higher AAST grades, associated injuries, diagnostic delay and inadequate or inappropriate initial treatment[15,27,28]. In the current study the number and severity of post-operative complications reflect the consequences of surgery in severe multiply injured patients. Associated injuries were common, in keeping with collateral damage seen with abdominal gunshot injuries. One half of patients had three or more associated injuries and the complexities of management were further compounded by associated vascular injuries present in one of every five patients. The dominant complications were infective, both intra-abdominal and systemic, respiratory, renal and related to bleeding. A substantial number of patients required a repeat laparotomy either for definitive management following an initial DCL (i.e., delayed resection) or for intra-abdominal infection unresolved after percutaneous catheter drainage, control of intra-abdominal bleeding, or for small bowel obstruction.

A variety of factors specifically contribute to the development of pancreas-related complications following trauma, including the mechanism and grade of the injury, especially GSWs and associated vascular, hollow viscus and solid organ injuries[29] and neglect of a main pancreatic duct injury may lead to local complications including pseudocysts, fistulas, sepsis and secondary hemorrhage[29]. Pancreatic fistulas occur in up to 38% of patients and intra-abdominal abscesses in 34%[29]. In a study from Los Angeles County Hospital pancreas-related complications developed in 27.9%, including pseudocysts in 14.9% and fistulas 1.9%[29].

Our data concur with the findings of others in that early deaths after major pancreatic trauma are related to the number and severity of associated injuries[30]. Overall mortality in this study was 14.6% with the presence of shock, due to associated vascular injuries being significantly related to early mortality. Late deaths were due to sepsis and MOF. Deaths specifically related to the pancreas were uncommon. A substantial number of patients required a repeat laparotomy either for definitive management following an initial DCL or for postoperative complications that could not be managed by percutaneous or endoscopic intervention. The DCL patients had a mortality of 31%. In a two-centre study from Philadelphia and Columbus, Ohio which sought to determine the optimal initial operative management in damage control operations, 42 patients with pancreatic injuries underwent either packing, drainage or resection. Mortality in their study population was substantial (packing only, 70%; packing with drainage, 25%, distal pancreatectomy, 55%)[30].

Although this study represents the largest detailed analysis of major pancreatic resections for trauma to date, there are several specific limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the data and outcome. The most substantial concern is that this is a single centre study in a high-volume tertiary referral centre and although these results may be similar to other major academic institutions, the data are not valid for community-based hospitals with lesser resources. The study design sought to avoid possible non-measurable biases that may result from patient selection, referral patterns and local differences in treatment policies by using complications and death as the main outcomes to provide consistent and objective end-points. A further concern is that the ASGS scores only the highest grade complication, without considering the burden of multiple but lesser complications in the same patient[31]. Specific strengths of the current study and of our analysis are the size of the cohort and the use of validated ISGPS definitions to score postoperative complications which have provided dependable and robust data and allowed reliable comparisons[8-11].

In conclusion, postoperative morbidity after pancreatic resection for trauma in this study was substantial and an increasing complication severity grade, as measured by the ASGS, required escalation of intervention and prolonged hospitalisation. The injured pancreas is an unforgiving organ, especially if severely damaged. Accurate intraoperative decision-making is crucial for a favourable outcome. A wide spectrum of options need to be considered, including initial damage control with delayed resection and/or reconstruction which is applicable as the default option in a select group of unstable patients. In applying the ASGS, we have established a benchmark for pancreatic resections for trauma by using current standardized definitions for grading severity of pancreatic complication. This will facilitate future comparative assessments and serve as a reference for improving outcome. Benchmarking is not restricted to comparative analyses of outcome, but should serve as a mechanism for transforming surgical practice and enhancing quality of care. To further develop this, future studies should include the calculation of the total burden of multiple complications in individual patients by utilising the comprehensive complication index, a factor which is relevant in trauma patients with several injured organs[32].

The pancreas is the least injured of the intra-abdominal solid organs but results in considerable morbidity and mortality rates if the injury is incorrectly assessed or inadequately treated. Outcome is influence by the complexity of the pancreatic injury, the number and severity of associated vascular and visceral injuries, the duration of shock and the quality and nature of surgical intervention. Two-thirds of patients who survive more than 48 h have major complications as a result of the pancreatic and associated injuries, and the one third of patients who die later do so because of intra-abdominal or systemic septic complications or multi-organ failure. Despite the substantial morbidity no studies have previously performed a detailed analysis of complications after pancreatic resection for trauma using standardized methodology.

There is consensus that the modern management of complex pancreatic trauma is best achieved by collaborative team work between trauma and pancreatic surgeons. However, the optimal management of complex pancreatic injuries remains undefined due to the lack of high quality evidence. Despite a plethora of papers on pancreatic trauma, none have specifically addressed the spectrum of complications as patterns of injury and methods of intervention have progressed. Earlier studies assessing outcome after pancreatic resections for major pancreatic injuries have applied unqualified primary endpoints with differing descriptions and definitions which consequently have resulted in flawed conclusions. This analysis evaluated post-resection complications by applying robust and reliable methodology and objective and reproducible end-points in a large cohort of consecutive patients treated at a tertiary referral center. Internationally accepted and validated definitions of complications and grading scores including the 6-scale Accordion Severity Grading System (ASGS) were used to benchmark the severity of complications.

The present study represents the largest single center series of patients undergoing pancreatic resection for trauma. The number and severity of post-operative complications reflect the consequences of surgery in severe multiply injured patients. Associated injuries were common, in keeping with collateral damage seen with abdominal gunshot injuries. One half of patients had three or more associated injuries and the complexities of management were further compounded by associated vascular injuries present in one of every five patients. The dominant complications were infective, both intra-abdominal and systemic, respiratory, renal and related to bleeding. A substantial number of patients required a repeat laparotomy either for definitive management following an initial damage control laparotomy (i.e., delayed resection) or for intra-abdominal infection unresolved after percutaneous catheter drainage, control of intra-abdominal bleeding, or for small bowel obstruction. Overall 73% of patients had complications of which three quarters were Accordion grades 3-6. Patients more likely to have complications after pancreatic resection were older, had a revised trauma score < 7.8, were shocked on admission, had grade 5 injuries of the head and neck of the pancreas with associated vascular and duodenal injuries, required a damage control laparotomy, received a larger blood transfusion, had a pancreatoduodenectomy and repeat laparotomies. Applying univariate logistic regression analysis, mechanism of injury, revised trauma score < 7.8, shock on admission, damage control laparotomy, increasing AAST grade and type of pancreatic resection were significant variables for complications. Multivariate logistic regression analysis however showed that only age and type of pancreatic resection were significant.

Postoperative morbidity after pancreatic resection for trauma in this study was considerable and an increasing complication severity grade, as measured by the ASGS, required escalation of intervention and prolonged hospitalisation. Accurate intraoperative decision-making is crucial for a favourable outcome. A wide spectrum of options need to be considered, including initial damage control with delayed resection and/or reconstruction which is applicable as the default option in a select group of unstable patients. In applying the Accordion scale, the authors have established a benchmark for pancreatic resections for trauma by using current standardized definitions for grading severity of pancreatic complication. This will facilitate future comparative assessments and serve as a reference for improving outcome. Benchmarking is not restricted to comparative analyses of outcome, but should serve as a mechanism for transforming surgical practice and enhancing quality of care. To further develop this, future studies should include the calculation of the total burden of multiple complications in individual patients by utilising the comprehensive complication index, a factor which is relevant in trauma patients with several injured organs.

The validated International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery definitions of complications after pancreatic surgery provided an accurate, robust and consistent method to allow reliable comparisons of the incidence of post-operative pancreatic fistulas, bleeding and delayed gastric emptying. Similarly, the 6-scale Accordion Severity Grading System which discriminates post-operative complication severity following elective surgery on the basis of escalating interventional criteria, is now widely accepted as a credible, scoring system which is easy to apply and is reproducible with minimal inter-observer variability.

This is an interesting article based on the management of complex pancreatic injuries in 461 patients over a twenty five-year period containing a lot of important data. It is a well-written paper, documented and with acceptable outcome in such severe injuries.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Africa

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Giger UF, Pavlidis TE, Ribeiro MAF S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | van der Wilden GM, Yeh D, Hwabejire JO, Klein EN, Fagenholz PJ, King DR, de Moya MA, Chang Y, Velmahos GC. Trauma Whipple: do or don’t after severe pancreaticoduodenal injuries? An analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB). World J Surg. 2014;38:335-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Thompson CM, Shalhub S, DeBoard ZM, Maier RV. Revisiting the pancreaticoduodenectomy for trauma: a single institution’s experience. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:225-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Antonacci N, Di Saverio S, Ciaroni V, Biscardi A, Giugni A, Cancellieri F, Coniglio C, Cavallo P, Giorgini E, Baldoni F. Prognosis and treatment of pancreaticoduodenal traumatic injuries: which factors are predictors of outcome? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharpe JP, Magnotti LJ, Weinberg JA, Zarzaur BL, Stickley SM, Scott SE, Fabian TC, Croce MA. Impact of a defined management algorithm on outcome after traumatic pancreatic injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Scollay JM, Yip VS, Garden OJ, Parks RW. A population-based study of pancreatic trauma in Scotland. World J Surg. 2006;30:2136-2141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yoon PD, Chalasani V, Woo HH. Use of Clavien-Dindo classification in reporting and grading complications after urological surgical procedures: analysis of 2010 to 2012. J Urol. 2013;190:1271-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Martin RC, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Quality of complication reporting in the surgical literature. Ann Surg. 2002;235:803-813. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3512] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 9. | Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1411] [Cited by in RCA: 1946] [Article Influence: 108.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2328] [Article Influence: 129.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:177-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Farrell RJ, Krige JE, Bornman PC, Knottenbelt JD, Terblanche J. Operative strategies in pancreatic trauma. Br J Surg. 1996;83:934-937. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Krige JE, Kotze UK, Hameed M, Nicol AJ, Navsaria PH. Pancreatic injuries after blunt abdominal trauma: an analysis of 110 patients treated at a level 1 trauma centre. S Afr J Surg. 2011;49:58, 60, 62-64 passim. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Chinnery GE, Krige JE, Kotze UK, Navsaria P, Nicol A. Surgical management and outcome of civilian gunshot injuries to the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2012;99 Suppl 1:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Krige JE, Kotze UK, Setshedi M, Nicol AJ, Navsaria PH. Prognostic factors, morbidity and mortality in pancreatic trauma: a critical appraisal of 432 consecutive patients treated at a Level 1 Trauma Centre. Injury. 2015;46:830-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Krige JE, Nicol AJ, Navsaria PH. Emergency pancreatoduodenectomy for complex injuries of the pancreas and duodenum. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:1043-1049. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Krige JE, Kotze UK, Setshedi M, Nicol AJ, Navsaria PH. Surgical Management and Outcomes of Combined Pancreaticoduodenal Injuries: Analysis of 75 Consecutive Cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:737-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, Jurkovich GJ, Champion HR, Gennarelli TA, McAninch JW, Pachter HL, Shackford SR, Trafton PG. Organ injury scaling, II: Pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J Trauma. 1990;30:1427-1429. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644-1655. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296-327. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Krige JE, Kotze UK, Setshedi M, Nicol AJ, Navsaria PH. Management of pancreatic injuries during damage control surgery: an observational outcomes analysis of 79 patients treated at an academic Level 1 trauma centre. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016; Mar 14; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Krige JE, Thomson SR. Operative strategies in pancreatic trauma - keep it safe and simple. S Afr J Surg. 2011;49:106-109. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Navsaria PH, Bunting M, Omoshoro-Jones J, Nicol AJ, Kahn D. Temporary closure of open abdominal wounds by the modified sandwich-vacuum pack technique. Br J Surg. 2003;90:718-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Thomson DA, Krige JE, Thomson SR, Bornman PC. The role of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in pancreatic trauma: a critical appraisal of 48 patients treated at a tertiary institution. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1362-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chinnery GE, Bernon M, Krige JE, Grotte A. Endoscopic stenting of high-output traumatic duodenal fistula. S Afr J Surg. 2011;49:88-89. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Roberts DJ, Bobrovitz N, Zygun DA, Ball CG, Kirkpatrick AW, Faris PD, Brohi K, D’Amours S, Fabian TC, Inaba K. Indications for Use of Damage Control Surgery in Civilian Trauma Patients: A Content Analysis and Expert Appropriateness Rating Study. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1018-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kao LS, Bulger EM, Parks DL, Byrd GF, Jurkovich GJ. Predictors of morbidity after traumatic pancreatic injury. J Trauma. 2003;55:898-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hwang SY, Choi YC. Prognostic determinants in patients with traumatic pancreatic injuries. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Recinos G, DuBose JJ, Teixeira PG, Inaba K, Demetriades D. Local complications following pancreatic trauma. Injury. 2009;40:516-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Seamon MJ, Kim PK, Stawicki SP, Dabrowski GP, Goldberg AJ, Reilly PM, Schwab CW. Pancreatic injury in damage control laparotomies: Is pancreatic resection safe during the initial laparotomy? Injury. 2009;40:61-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee MK, Lewis RS, Strasberg SM, Hall BL, Allendorf JD, Beane JD, Behrman SW, Callery MP, Christein JD, Drebin JA. Defining the post-operative morbidity index for distal pancreatectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:915-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Slankamenac K, Nederlof N, Pessaux P, de Jonge J, Wijnhoven BP, Breitenstein S, Oberkofler CE, Graf R, Puhan MA, Clavien PA. The comprehensive complication index: a novel and more sensitive endpoint for assessing outcome and reducing sample size in randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2014;260:757-762; discussion 762-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |