Published online Feb 27, 2017. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i2.68

Peer-review started: October 8, 2016

First decision: November 14, 2016

Revised: December 4, 2016

Accepted: December 28, 2016

Article in press: December 28, 2016

Published online: February 27, 2017

Processing time: 144 Days and 17.4 Hours

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma (ESOS) is an uncommon tumor that accounts for 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas and 4% of all osteosarcomas. Its presentation may be atypical, while pain has been described as the most common symptom. Radiological findings include a large mass in the soft-tissues with massive calcifications, but no attachment to the adjacent bone or periosteum. We present the case of a 73-year-old gentle man who presented with a palpable, tender abdominal mass and symptoms of bowel obstruction. Computer tomography images revealed a large space-occupying heterogeneous, hyper dense soft tissue mass involving the small intestine. Explorative laparotomy revealed a large mass in the upper mesenteric root of the small intestine, measuring 22 cm × 12 cm × 10 cm in close proximity with the cecum, which was the cause of the bowel obstruction. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of an ESOS. ESOS is an uncommon malignant soft tissue tumor with poor prognosis and a 5-year survival rate of less than 37%. Regional recurrence and distant metastasis to lungs, regional lymph nodes and liver can occur within the first three years of diagnosis in a high rate (45% and 65% respectively). Wide surgical resection of the mass followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy has been the treatment of choice.

Core tip: We present the case of an elderly man who presented with a palpable abdominal mass and signs of intestinal obstruction. Intra-operative findings revealed a mass in the right abdomen involving the small intestine, which was widely resected. A diagnosis of soft tissue osteosarcoma was confirmed by pathology; further treatment with chemotherapy followed. To our knowledge it has never been reported a case of abdominal obstruction due to soft tissue sarcoma in the literature. Due to its rarity, we strongly believe that the presentation of this case would contribute to further understanding of the biology and management of this tumor.

- Citation: Diamantis A, Christodoulidis G, Vasdeki D, Karasavvidou F, Margonis E, Tepetes K. Giant abdominal osteosarcoma causing intestinal obstruction treated with resection and adjuvant chemotherapy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 9(2): 68-72

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v9/i2/68.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v9.i2.68

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma (ESOS) is a rare mesenchymal malignant soft tissue neoplasm. It constitutes 1%-2% of all soft-tissue sarcomas and 4%-5% of all osteosarcomas, while it is considered to be an aggressive tumor with an overall 5 year mortality rate up to 60%[1-3]. Patients are usually affected in the 6th decade of life and men are affected with a slightly higher frequency than women[4,5]. Their exact pathogenesis is not clear; even though there is some evidence that ESOS can be associated with trauma, radiation and radiotherapy[2,4]. The most common location includes the deep soft tissue of the thigh (47%), the upper extremity (20%) and the peritoneum (17%)[4].

We present a unique case of intestinal obstruction due to a giant abdominal osteosarcoma treated with resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A 73-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with a two-week history of abdominal pain, progressive appetite loss, vomiting and constipation, with no reported weight loss. There was no history of pathological fractures. Physical examination revealed a palpable, tender mass in the central abdomen without any signs of acute abdomen or ascites.

Standard blood tests showed a mild increase in inflammatory markers (white blood cells, C-reactive protein), while tumor markers (CEA, CA19-9, AFP, PSA) were within normal limits.

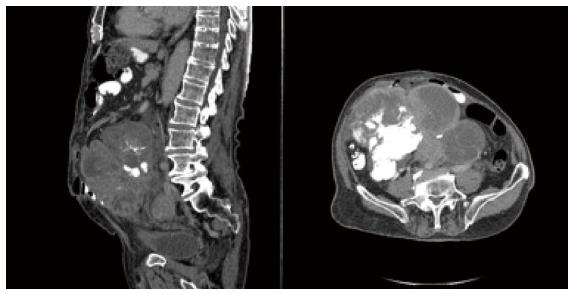

Abdominal radiograph revealed air-fluid levels, as well as a rounded, densely calcified mass mainly occupying the right abdomen. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a large space occupying, heterogeneous soft tissue mass with cystic spaces involving the small intestine, surrounded by multiple massively enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 1).

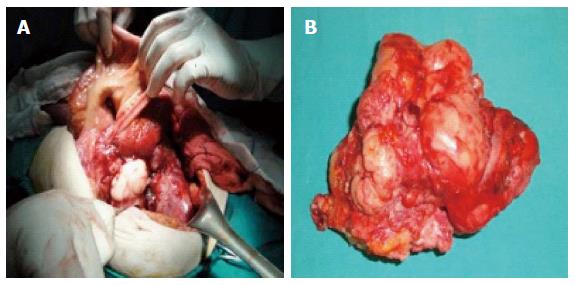

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy. The intraoperative findings included a large mass in the upper mesenteric root of the small intestine, measuring 22 cm × 12 cm × 10 cm, occupying the right abdomen (Figure 2A). The tumor was in close proximity with the cecum, the right kidney and the urinary bladder and there were no signs of invasion to the surrounding organs or distant metastasis. There were also enlarged lymph nodes in proximity to the lesion. The tumor was excised en bloc with a 40 cm part of the ileum and lymph nodes of the mesenteric (Figure 2B).

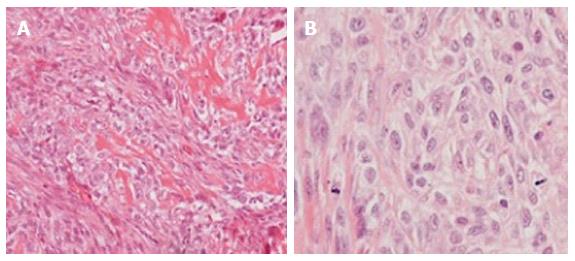

Microscopic examination, with the use of Haematoxylin and Eosin stain, confirmed the diagnosis of soft tissue osteosarcoma (Figure 3).

In the multidisciplinary team meeting was decided that the oncologists should follow up the patient. The patient was furthermore treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (Adriamycin and Ifosfamide) and three years after surgery he remained disease free.

ESOS is an uncommon tumor that accounts for 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas and 4% of all osteosarcomas. It affects most commonly individuals older than 30 years. It has a mesenchymal origin that produces osseous components such as bone, osteoid and chondroid without being attached to the bone or the periosteum. History of trauma is related with soft tissue osteosarcoma as well as former radiotherapy especially in the breast region[1,6,7]. The most common sites where the soft-tissue osteosarcoma may arise are the deep tissue of the thigh, the upper and lower extremity and the retroperitoneum. However, few cases of ESOS have been reported arising in unusual sites, such as the larynx, kidney, esophagus, small intestine, liver, heart, urinary bladder, parotid, and breast[8].

The main symptoms include a slowly enlarging and painful mass while in some cases ulceration of the mass has been reported. To our knowledge a case report of intestinal obstruction due to a giant ESOS has never been reported in literature before.

These tumors are usually large at the time of diagnosis, with an average diameter of 9 cm. The size of the tumor constitutes a significant prognostic factor. Patients with a tumor size > 5 cm have usually a worse outcome despite the radical treatment. However, in some studies, the small size of the tumor did not result in a better prognosis or a long-term survival[7].

According to Allan et al[1], the diagnostic criteria of ESOS are the presence of a major morphological pattern of sarcomatous tissue and the production of malignant bone or osteoid, whose origin is not osseous. The microscopic examination reveals atypical spindled and epithelioid mesenchymal cells that produce a lace-like, abnormal osteoid. There is an increase of mitoses with pleomorphic cells, with or without deposition of hyaline cartilage. The tumor osteoid and bone is centrally located with a lucent edge, which is the reverse zonation from that seen in myositis ossificans[1]. Various types of soft-tissue osteosarcoma are reported, each of which follows a different histological pattern. The usual patterns include the chondroblastic, fibroblastic, telangiectatic, and small cell. Although a tumor can include more than 2 histological patterns, in case the major histological pattern represents 75% or more of the tumor, this specific type characterizes the lesion.

The immunohistochemical search usually shows that the neoplastic cells are positive for vimentin, alpha smooth muscle actin and osteonectin, CD99, S100 but are negative for c-kit, CD34, cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, and desmin.

The radiological images of ESOS often present similarities with the images of parosteal osteosarcoma, however the parosteal osteosarcoma has a broad attachment to thickened cortical bone. The radiographs and the CT present ESOS as a large mass in the soft-tissues with massive calcifications, with no attachment to the adjacent bone or periosteum. The MRI images present a nonspecific intermediate signal on T1-weighted imaging and high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging, which is enhanced by the administration of gadolinium. The presence of a pseudocapsule has also been reported. The tumor presents an increased radiotracer uptake in scintigraphy. Finally, the ESOS is presented as a multilobulated large mass with mineralized components and abnormal uptake on F-18-FDG PET/CT fusion images.

The diagnosis of ESOS should be made using the combination of the atypical clinical manifestations, the radiographical findings and the pathological verification. The differential diagnosis of the soft-tissue osteosarcoma includes various malignant and benign entities of soft-tissue origin[5], such as myositis ossificans, liposarcoma and histiocytoma.

ESOS has a high rate of regional recurrence (45%) and distant metastasis (65%). Common sites of involvement are the lungs (80%), the regional lymph nodes and the liver. Recurrence and/or metastasis usually occur within the first three years of the diagnosis[5].

Treatment of ESOS consists of wide surgical resection of the tumor or amputation combined with adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. Even though ESOS is considered to be of low responsiveness to radiotherapy and/or to chemotherapy, with a response rate to chemotherapy up to 45%, the survival and recurrence rate may be reduced by postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, while radiotherapy is still questioned for its results[9-11]. Goldstein-Jackson et al[12] recommend that all ESOS should be treated like conventional osteosarcoma with a combination of multiagent chemotherapy and surgery.

Finally, the prognosis is quite poor and a large percentage of the cases succumb to metastatic disease or recurrence within 2-3 years of the diagnosis with an overall 5-year mortality up to 60%.

In conclusion, ESOS is an unusual high-grade malignant soft tissue neoplasm with a poor prognosis and a 5-year survival rate less than 37%. Multiagent chemotherapy following radical surgery seems to be the best choice to treat these patients while radiation may also contribute in some cases. A careful follow-up of patients with soft-tissue osteosarcoma is required because of the high rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis despite the radical treatment.

A 73-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a two-week history of abdominal pain, progressive appetite loss, vomiting and constipation, with no reported weight loss.

Physical examination revealed a palpable, tender mass in the central abdomen without any signs of acute abdomen or ascites.

The diagnosis of extraskeletal osteosarcoma (ESOS) should be made using the combination of the atypical clinical manifestations, the radiographical findings and the pathological verification.

Standard blood tests showed a mild increase in inflammatory markers (white blood cells, C-reactive protein), while tumor markers (CEA, CA19-9, AFP, PSA) were within normal limits.

An abdominal radiograph and a computed tomography of the abdomen were performed with the findings discussed in the text.

Microscopic examination, with the use of haematoxylin and eosin stain, confirmed the diagnosis of soft tissue osteosarcoma.

Wide surgical excision of the lesion and the involved intestine.

ESOS is an uncommon mesenchymal tumor that produces osseous components such as bone, osteoid and chondroid without being attached to the bone or the periosteum and accounts for 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas and 4% of all osteosarcomas.

Multiagent chemotherapy following radical surgery seems to be the best choice to treat these patients while radiation also may contribute in some cases. A careful follow-up of patients with soft-tissue osteosarcoma is required because of the high rates of local recurrence.

This is a well written case report.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cibor D, Ciccone MM, Mitsui K, Okello M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Allan CJ, Soule EH. Osteogenic sarcoma of the somatic soft tissues. Clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of literature. Cancer. 1971;27:1121-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chung EB, Enzinger FM. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1987;60:1132-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McCarter MD, Lewis JJ, Antonescu CR, Brennan MF. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma: analysis of outcome of a rare neoplasm. Sarcoma. 2000;4:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee JS, Fetsch JF, Wasdhal DA, Lee BP, Pritchard DJ, Nascimento AG. A review of 40 patients with extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1995;76:2253-2259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sordillo PP, Hajdu SI, Magill GB, Golbey RB. Extraosseous osteogenic sarcoma. A review of 48 patients. Cancer. 1983;51:727-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bane BL, Evans HL, Ro JY, Carrasco CH, Grignon DJ, Benjamin RS, Ayala AG. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma. A clinicopathologic review of 26 cases. Cancer. 1990;65:2762-2770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alpert LI, Abaci IF, Werthamer S. Radiation-induced extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1973;31:1359-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Olgyai G, Horváth V, Banga P, Kocsis J, Buza N, Oláh A. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma located to the gallbladder. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8:65-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ahmad SA, Patel SR, Ballo MT, Baker TP, Yasko AW, Wang X, Feig BW, Hunt KK, Lin PP, Weber KL. Extraosseous osteosarcoma: response to treatment and long-term outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:521-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Torigoe T, Yazawa Y, Takagi T, Terakado A, Kurosawa H. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma in Japan: multiinstitutional study of 20 patients from the Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12:424-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sio TT, Vu CC, Sohawon S, Van Houtte P, Thariat J, Novotny PJ, Miller RC, Bar-Sela G. Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma: An International Rare Cancer Network Study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:32-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Goldstein-Jackson SY, Gosheger G, Delling G, Berdel WE, Exner GU, Jundt G, Machatschek JN, Zoubek A, Jürgens H, Bielack SS. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma has a favourable prognosis when treated like conventional osteosarcoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:520-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |