Published online Oct 27, 2017. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i10.209

Peer-review started: June 2, 2017

First decision: July 26, 2017

Revised: August 27, 2017

Accepted: September 5, 2017

Article in press: September 6, 2017

Published online: October 27, 2017

Processing time: 148 Days and 18.5 Hours

Pregnancy is an acquired hypercoagulable state. Most patients with thrombosis that develops during pregnancy present with deep vein leg thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism, whereas the development of mesenteric vein thrombosis (MVT) in pregnant patients is rare. We report a case of MVT in a 34-year-old woman who had achieved pregnancy via in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET). At 7 wk of gestation, the patient was referred to us due to abdominal pain accompanied by vomiting and hematochezia, and she was diagnosed with superior MVT. Following resection of the gangrenous portion of the small intestine, anticoagulation therapy with unfractionated heparin and thrombolysis therapy via a catheter placed in the superior mesenteric artery were performed, and the patient underwent an artificial abortion. Oral estrogen had been administered for hormone replacement as part of the IVF-ET procedure, and additional precipitating factors related to thrombosis were not found. Pregnancy itself, in addition to the administered estrogen, may have caused MVT in this case. We believe that MVT should be included in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant patient who presents with an acute abdomen.

Core tip: Pregnancy is a hypercoagulable state that can lead to mesenteric vein thrombosis (MVT). Those symptoms are often nonspecific. Certain signs of MVT can be interpreted as normal changes during the progression of pregnancy; therefore, it is important to recognize the possibility of the development of MVT in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant patient with an acute abdomen. Estrogen can also cause thrombosis and is often administered for hormone replacement as part of an assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedure, particularly in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. With further development of ART, the number of women taking oral estrogen during pregnancy may increase.

- Citation: Hirata M, Yano H, Taji T, Shirakata Y. Mesenteric vein thrombosis following impregnation via in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 9(10): 209-213

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v9/i10/209.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v9.i10.209

It is well known that pregnancy and estrogen are risk factors for thrombosis. The development of thrombosis during pregnancy is multifactorial, occurring due to physiological changes associated with pregnancy and the additional impact of inherited or acquired thrombophilia[1]. Deep vein leg thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism are the presentations of most events in affected patients. However, mesenteric vein thrombosis (MVT) that develops during pregnancy is rare; only 10 known cases involving this condition have previously been reported.

We present here a case of MVT in a 34-year-old pregnant woman at 7 wk of gestation. Pregnancy had been achieved via in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET), and oral estrogen had been administered for hormone replacement as part of that procedure. This is the first report of MVT that developed after impregnation achieved via IVF-ET.

At 7 wk of gestation, a 34-year-old Japanese woman, gravida 0, para 0, was referred to our emergency department from a reproductive clinic for abdominal pain that had lasted for 12 h and was accompanied by vomiting and hematochezia. Nausea had appeared 4 d prior and was treated as hyperemesis gravidarum. The patient had a history of infertility related to endometriosis, and pregnancy was achieved after her first IVF procedure with frozen-thawed embryo transfer. As part of that procedure, oral conjugated equine estrogen (3.75 mg/d) was administered for hormone replacement for 49 d; the patient also received intramuscular injections of progesterone (50 mg/4 d) and a vaginal progesterone suppository (800 mg/d). She was a nonsmoker and had no prior history suggestive of thrombosis. She had no family history of coagulopathies or thromboembolic events. The patient underwent a laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for endometriosis 4 years prior to her presentation at our hospital. Her body mass index was 24 kg/m2.

Upon arrival, the patient exhibited the following vital signs: A temperature of 36.8 °C, a heart rate of 119 beats/min, a blood pressure of 89/76 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 28/min, and oxygen saturation of 97% in room air. A physical examination showed tenderness without guarding, rigidity or rebound tenderness throughout the entire abdomen, and a hematologic examination revealed leukocytosis with a left shift (white blood cell count, 21000/μL; segmented neutrophils, 94.9%). The platelet count was 142000/μL. The patient had a C-reactive protein level of 5.13 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase level of 23 U/L (normal, 13-30 U/L), alanine aminotransferase level of 29 U/L (normal, 7-23 U/L), serum creatinine level of 0.58 mg/dL, and blood urea nitrogen level of 14.3 mg/dL. Her D-dimer level was elevated (46.8 μg/mL; normal, < 1.0 μg/mL), the prothrombin time was 13.4 s (normal, 10.2-13.6 s), and the activated partial thromboplastin time was 24.1 s (normal, 23.0-36.0 s). The findings of a hypercoagulability workup, including results for protein S, protein C, and antithrombin, were within normal limits. Anticardiolipin antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant were not detected. She refused screens of the FV Leiden mutation and FII G20210A mutations, which are not found in Japanese people. JAK2 V617F mutation was also not screened because hemoglobin and platelets were in the normal range.

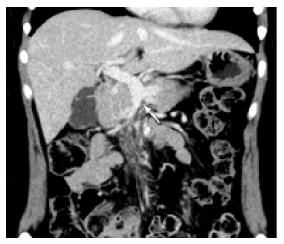

Obstetric ultrasound indicated that the embryo had a normal appearance compatible with its gestational age. Computed tomography (CT) scanning demonstrated thrombosis in the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) extending into the portal vein (Figure 1). A moderate amount of ascites was observed, and the affected small bowel had an edematous and thickened wall with decreased enhancement, which suggested bowel ischemia.

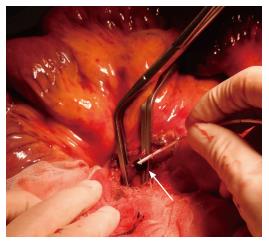

Emergency surgical exploration was performed; this exploration found hemorrhagic fluid and a gangrenous portion of the small intestine extending from 80 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz to 160 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve (Figure 2). After the surgical removal of SMV thrombi (Figure 3), the necrotic portion of the small bowel, which was approximately 170 cm in length, was resected, and end-to-end anastomosis was performed. Following surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, and anticoagulation therapy with unfractionated heparin was started immediately. We confirmed cardiac activity in the embryo by ultrasonography.

The subsequent postoperative course was not favorable. CT scanning on postoperative day 4 demonstrated re-occlusion of the SMV and portal vein and no improvement in small bowel congestion. Thrombolysis therapy via a catheter placed in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) was performed by continuously administering unfractionated heparin with urokinase via the SMA at a dose of 240000 units/d for 5 d. In addition to thrombolysis therapy, we discussed artificial abortion with the patient; after obtaining consent, we performed this procedure due to the early pregnancy stage and the recurrence of thrombosis despite heparin administration. Following the artificial abortion, the patient’s condition improved, and she was discharged on postoperative day 18 with bridging to warfarin from unfractionated heparin.

Four months later, the patient continued to receive anticoagulation therapy uneventfully, and a follow-up CT scan revealed complete recanalization of the portal vein, and the SMV was completely occluded from the distal to the first jejunal branches (Figure 4). The first jejunal vein was expanding and functioning as a collateral pathway. The follow-up laboratory data were as follows: Platelet count, 260000/μL; aspartate aminotransferase level, 19 U/L (normal, 13-30 U/L); alanine aminotransferase level, 17 U/L (normal, 7-23 U/L); serum creatinine level, 0.54 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen level, 11.1 mg/dL; D-dimer level, 0.5 μg/mL (normal, < 1.0 μg/mL); prothrombin time on warfarin, 19.3 s (normal, 10.2-13.6 s); and activated partial thromboplastin time, 31.5 s (normal, 23.0-36.0 s). She had normal liver function, no symptoms of portal hypertension, and had no ascites. We plan to continue anticoagulation therapy for one year.

This article provides the first description of MVT that developed following impregnation achieved via IVF-ET. We could not identify factors related to inherited or acquired thrombophilia in this case. We believe that the relative hypercoagulability induced by pregnancy, in addition to the administration of oral estrogen during hormone replacement as part of the IVF-ET procedure, may have caused MVT in this patient, who lacked other precipitating factors.

The overall rate of venous thromboembolic events during pregnancy is 200 per 100000 deliveries[2]. Deep vein leg thrombosis and pulmonary embolism have been recognized as related events, whereas MVT is rare, with only 10 previously documented cases of MVT occurring in pregnant patients.

MVT is a life-threatening form of bowel ischemia, with an estimated mortality rate ranging from 20%-50%[3]. Symptoms of MVT are often nonspecific and include colic, progressive abdominal pain, anorexia, and abdominal distention. In pregnant patients, signs related to MVT are most likely interpreted as normal changes associated with the progression of pregnancy; as a result, MVT is difficult to accurately diagnose. In the present case, nausea appeared 4 d prior to the development of abdominal pain and, might have been a prodromal symptom rather than an indication of hyperemesis gravidarum. For accurate diagnosis, careful observation is necessary with MVT in mind, and abdominal enhanced CT scanning is recommended[3]. A delay in diagnosis may lead to unfavorable results for both the mother and the fetus. Once a diagnosis of MVT is established, immediate treatment with anticoagulation therapy and/or surgical exploration is necessary if an ischemic bowel is suspected. Thrombolysis therapy via a catheter placed in the SMA may be managed if thrombosis worsens despite anticoagulation therapy with heparin, although urokinase carries the risk of fetal hemorrhagic complications. Thrombosis due to underlying prothrombotic states, including pregnancy, begins in small vessels and progresses to involve larger vessels. Considering this pathogenesis, thrombolysis therapy at the SMA may be recommended.

In this case, we also selected artificial abortion for the following three reasons. First, screens for inherited thrombotic disorders were negative, and pregnancy itself may have caused the thrombosis. Second, thrombosis may have recurred during pregnancy because of the diagnosis during early pregnancy. Third, the health of the mother is given priority.

Life-long anticoagulation is warranted in patients with inherited thrombophilia, whereas anticoagulation therapy for at least 6 mo to one year is recommended for patients with reversible predisposing causes, including pregnancy[3]. Therefore we planned to continue anticoagulation therapy for one year.

The development of MVT during pregnancy is multifactorial, occurring due to physiological changes related to pregnancy and the additional impact of inherited or acquired thrombophilia. Clinical features noted in the 10 previously reported cases and the present case of MVT in a pregnant patient are shown in Table 1. Causes of the development of MVT in these cases were pregnancy itself in 5 patients, hypercoagulopathy in 3 patients, and hemoglobinopathy in 1 patient. Oral estrogen was administered during pregnancy in 2 cases, including the present case.

| Case | Ref. | Year | Age | Gestation (wk) | Additional risk | Intestinal resection | Pregnancy outcome |

| 1 | Van Way et al[7] | 1970 | 33 | 12 | - | Yes | ND |

| 2 | Graubard et al[8] | 1987 | 30 | 14 | Oral contraceptives by mistake | Yes | ND |

| 3 | Engelhardt et al[9] | 1989 | 32 | ND | - | Yes | Live birth |

| 4 | Foo et al[10] | 1996 | 27 | 6 | - | − | Artificial abortion |

| 5 | Sönmezer et al[11] | 2004 | 32 | 27 | Factor V Leiden mutation | − | Live birth |

| 6 | Terzhumanov et al[12] | 2005 | 33 | ND | Hemoglobinopathy | Yes | Miscarriage |

| 7 | Atakan et al[13] | 2009 | 35 | 20 | Protein S deficiency | Yes | Maternal death |

| 8 | Lin et al[14] | 2011 | 31 | 34 | - | Yes | Live birth |

| 9 | García-Botella et al[15] | 2016 | 29 | 7 | Antithrombin deficiency | Yes | Live birth |

| 10 | Reiber et al[16] | 2016 | 30 | ND | - | Yes | Live birth |

| 11 | Present case | 2017 | 34 | 7 | Oral estrogen associated with IVF-ET | Yes | Artificial abortion |

MVT development in our patient was associated with pregnancy achieved via IVF-ET, which is the most common assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedure used for infertility. In this case, IVF and frozen-thawed embryo transfer were performed; during this process, exogenous steroids (estrogen and progesterone) are often administered to prepare the endometrium to receive the thawed embryos and to ensure that the timing of endometrial preparation and embryo development coincide. Among steroids, oral contraceptives (OC) are known to be a risk factor for MVT[3], and OC accounts for 9%-18% of episodes of MVT in young women[4,5]. It is difficult to compare the effects of conjugated equine estrogen with those of OC because of differences in dosage and biological effects. However, in the present case, the administration of conjugated equine estrogen, in addition to pregnancy itself, might have caused similar MVT-related effects to those observed for OC. With the development of ART, the number of pregnant women taking estrogen during pregnancy may increase, which could lead to the more frequent development of thrombosis, including MVT.

Antepartum thrombo-prophylaxis is generally recommended for pregnant women with prior thrombosis[6]. However, findings regarding the risk of thrombosis in women with prior thrombosis who undergo ART are lacking, and dosage and thrombo-prophylaxis duration after ART have not been well investigated. For the present patient, another pregnancy may be difficult to achieve because infertility treatment without estrogen will be necessary.

In conclusion, pregnancy can increase the risk of MVT, which should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant patient with an acute abdomen. In cases of pregnancy achieved via IVF-ET, particularly frozen-thawed embryo transfer, the risk of thrombosis, including MVT, may be further increased due to the administration of estrogen for hormone replacement.

A 34-year-old woman was referred to the authors’ hospital because of abdominal pain accompanied by vomiting and hematochezia.

The patient was diagnosed with acute mesenteric ischemia.

The different diagnosis was hyperemesis gravidarum.

An elevated D-dimer level suggested thrombosis.

Computed tomography scanning demonstrated thrombosis in the superior mesenteric vein extending into the portal vein.

Ischemic changes, including necrosis of the small bowel, were observed.

The administered treatment was resection of the necrotic portion of the small bowel, anticoagulant therapy with unfractionated heparin, and urokinase continuously administered via the superior mesenteric artery.

Mesenteric vein thrombosis (MVT) that develops during pregnancy is rare; only 10 known cases of this condition have previously been reported. This article provides the first report of MVT that developed following impregnation achieved via in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer.

MVT should be included in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant patient who presents with an acute abdomen.

This is an interesting case highlighting the potential for a serious albeit infrequent complication of ART.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aday AW, Lazo-Langner A, Qi XS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Battinelli EM, Marshall A, Connors JM. The role of thrombophilia in pregnancy. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:516420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR, Melton LJ 3rd. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:697-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 887] [Cited by in RCA: 838] [Article Influence: 41.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1683-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Abdu RA, Zakhour BJ, Dallis DJ. Mesenteric venous thrombosis--1911 to 1984. Surgery. 1987;101:383-388. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Harward TR, Green D, Bergan JJ, Rizzo RJ, Yao JS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, Veenstra DL, Prabulos AM, Vandvik PO. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e691S-e736S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1026] [Cited by in RCA: 892] [Article Influence: 68.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Van Way CW 3rd, Brockman SK, Rosenfeld L. Spontaneous thrombosis of the mesenteric veins. Ann Surg. 1971;173:561-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Graubard ZG, Friedman M. Mesenteric venous thrombosis associated with pregnancy and oral contraception. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1987;71:453. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Engelhardt TC, Kerstein MD. Pregnancy and mesenteric venous thrombosis. South Med J. 1989;82:1441-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Foo E, Sim R, Ng BK. Case report of acute splenic and superior mesenteric vein thrombosis and its successful medical management. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:755-758. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sönmezer M, Aytaç R, Demirel LC, Kurtay G. Mesenteric vein thrombosis in a pregnant patient heterozygous for the factor V (1691 G --> A) Leiden mutation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114:234-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Terzhumanov R, Uchikova E, Paskaleva V, Milchev N, Uchikov A. [Mesenteric venous trombosis and pregnancy--a case report and a short review of the problem]. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia). 2005;44:47-49. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Atakan Al R, Borekci B, Ozturk G, Akcay MN, Kadanali S. Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis due to protein S deficiency in a pregnant woman. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35:804-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lin H, Lin CC, Huang WT. Idiopathic superior mesenteric vein thrombosis resulting in small bowel ischemia in a pregnant woman. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:687250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | García-Botella A, Asenjo S, De la Morena-Barrio ME, Corral J, Bolaños E, Carlin PS, López ES, García AJ. First case with antithrombin deficiency, mesenteric vein thrombosis and pregnancy: Multidisciplinary diagnosis and successful management. Thromb Res. 2016;144:72-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Reiber BM, Gorter RR, Tenhagen M, Cense HA, Demirkiran A. [Mesenteric venous thrombosis during pregnancy; a rare cause of acute ischaemia of the small intestine]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2016;160:A9898. [PubMed] |