Published online Jul 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i7.508

Peer-review started: January 25, 2016

First decision: March 25, 2016

Revised: April 9, 2016

Accepted: April 21, 2016

Article in press: April 22, 2016

Published online: July 27, 2016

Processing time: 168 Days and 13.3 Hours

AIM: To report our experience with perineal repair (Delorme’s procedure) of rectal prolapse with particular focus on treatment of the recurrence.

METHODS: Clinical records of 40 patients who underwent Delorme’s procedure between 2003 and 2014 were reviewed to obtain the following data: Gender; duration of symptoms, length of prolapse, operation time, ASA grade, length of post-operative stay, procedure-related complications, development and treatment of recurrent prolapse. Analysis of post-operative complications, rate and time of recurrence and factors influencing the choice of the procedure for recurrent disease was conducted. Continuous variables were expressed as the median with interquartile range (IQR). Statistical analysis was carried out using the Fisher exact test.

RESULTS: Median age at the time of surgery was 76 years (IQR: 71-81.5) and there were 38 females and 2 males. The median duration of symptoms was 6 mo (IQR: 3.5-12) and majority of patients presented electively whereas four patients presented in the emergency department with irreducible rectal prolapse. The median length of prolapse was 5 cm (IQR: 5-7), median operative time was 100 min (IQR: 85-120) and median post-operative stay was 4 d (IQR: 3-6). Approximately 16% of the patients suffered minor complications such as - urinary retention, delayed defaecation and infected haematoma. One patient died constituting post-operative mortality of 2.5%. Median follow-up was 6.5 mo (IQR: 2.15-16). Overall recurrence rate was 28% (n = 12). Recurrence rate for patients undergoing an urgent Delorme’s procedure who presented as an emergency was higher (75.0%) compared to those treated electively (20.5%), P value 0.034. Median time interval from surgery to the development of recurrence was 16 mo (IQR: 5-30). There were three patients who developed an early recurrence, within two weeks of the initial procedure. The management of the recurrent prolapse was as follows: No further intervention (n = 1), repeat Delorme’s procedure (n = 3), Altemeier’s procedure (n = 5) and rectopexy with faecal diversion (n = 3). One patient was lost during follow up.

CONCLUSION: Delorme’s procedure is a suitable treatment for rectal prolapse due to low morbidity and mortality and acceptable rate of recurrence. The management of the recurrent rectal prolapse is often restricted to the pelvic approach by the same patient-related factors that influenced the choice of the initial operation, i.e., Delorme’s procedure. Early recurrence developing within days or weeks often represents a technical failure and may require abdominal rectopexy with faecal diversion.

Core tip: Delorme’s procedure is an attractive and often the only treatment of rectal prolapse available to elderly individuals who often have no physiological reserves to withstand abdominal rectopexy. The management of the recurrent disease is frequently restricted to the perineal approach by the same patient-related factors that limited the choice of the initial operation. Early recurrence developing within days or weeks is difficult to treat and in sufficiently fit patients may require abdominal rectopexy combined with faecal diversion.

- Citation: Javed MA, Afridi FG, Artioukh DY. What operation for recurrent rectal prolapse after previous Delorme’s procedure? A practical reality. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(7): 508-512

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i7/508.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i7.508

Full-thickness prolapse of the rectum is defined as a complete protrusion of the rectal wall through the anus. Although benign, the disease can be debilitating and affect patients’ quality of life. The incidence of rectal prolapse is reported as 10 per 1000 in patients aged over 65 years[1] and the majority of affected individuals (80%-95%) are women.

More than 130 surgical operations have been described to treat the prolapse which can broadly be classified into perineal and abdominal procedures, indicating that none is entirely satisfactory[2]. Perineal repair of rectal prolapse, as we understand it now, was named after Edmond Delorme - a French military surgeon who described a technique of mucosal stripping for treatment of procidentia in 1899[3]. It gained popularity and today remains the most frequently used type of perineal procedure. In elderly patients with significant co-morbidities Delorme’s is often a first choice procedure being the least invasive and, therefore, carrying less of surgical and anaesthetic risks. The perceived disadvantage of Delorme’s procedure is high rates of prolapse recurrence making it sub-optimal operation for young and healthy patients who are able to withstand abdominal rectopexy[4]. The choice of the procedure to deal with the recurrent rectal prolapse is often even more difficult due to the absence of established consensus among colorectal surgeons or guidelines to support decision-making process.

The primary aim of this study was to analyse our experience with the treatment of recurrent rectal prolapsed after failed perineal repair (Delorme’s procedure) and, in particular, factors that influenced further management. We also report our experience with Delorme’s procedure as a treatment of primary rectal prolapse.

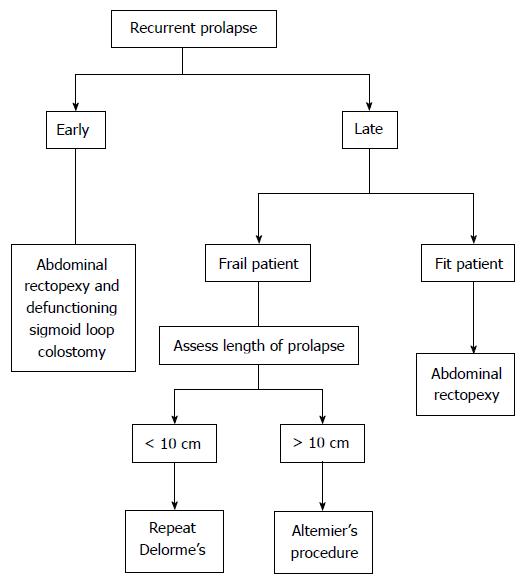

This was a retrospective observational study where we identified 40 consecutive cases of patients who underwent perineal repair of rectal prolapse (Delorme’s procedure) by one specialist team (DYA) in Southport and Ormskirk Hospital and Renacres Hospital between 2003 and 2014. Only patients who underwent Delorme’s operation as the first procedure undertaken by the team were included. Patients undergoing all other types of perineal procedures, such as excision of mucosal prolapse and perineal recto-sigmoidectomy (Altemier’s procedure) were excluded. All patient records were analysed to obtain the following data: Gender; duration of symptoms, length of prolapse, operation time, ASA grade, length of post-operative stay, procedure-related complications, development and treatment of recurrent prolapse and factors influencing the choice of the procedure for recurrent disease. Post-operative complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification[5]. The last follow-up date was considered as the date of the last documented physical examination. Treatment algorithm used for management of recurrent rectal prolapse is shown in Figure 1.

Continuous variables were expressed using non-parametric statistics, median with interquartile range (IQR), due to small sample size. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Fischer exact test. Results were considered significant with a probability value of P < 0.05. All calculations were performed using Origin software (OriginPro 9). Statistical methods used in the study were independently evaluated by an expert in Biomedical Statistics.

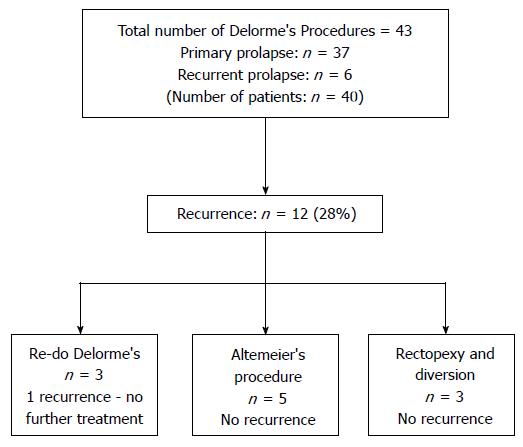

There were 38 females and 2 males in our cohort with the median age of 76 years (IQR: 71-81.5) at the time of surgery (Table 1). The median duration of symptoms was 6 mo (IQR: 3.5-12). Thirty six patients presented electively whereas four patients presented in the emergency department with irreducible rectal prolapse. The median length of prolapse was 5 cm (IQR: 5-7), median operative time was 100 min (IQR: 85-120) and median post-operative stay was 4 d (IQR: 3-6). The majority of patients had no post-operative complications, seven (16%) suffered minor complications, i.e., grade 1 or 2 such as - urinary retention, delayed defaecation and infected haematoma - as defined by Clavien-Dindo classification. One patient died of pneumonia and congestive cardiac failure due to ischaemic heart disease, constituting post-operative mortality of 2.5%. Median follow-up was 6.5 mo (IQR: 2.15-16). Surgical morbidity was higher in patients undergoing surgery for recurrent rectal prolapse (2/7, 28.5%) vs primary Delorme’s (4/36, 11.1%), P value 0.004, and the only mortality in the case series was that of a patient who had surgery for recurrent prolapse. Peri-operative and follow up data are shown in Table 2. Median duration of follow-up was 6.5 mo (range from 2 to 16 mo), the overall recurrence rate was 28% (n = 12). A summary of patients’ outcome is shown in Figure 2. Recurrence rate for patients undergoing an urgent Delorme’s procedure who presented as an emergency was higher (3/4, 75%) compared to those treated electively (9/39, 23%), P value 0.034. No other factors included in the analysis were identified to be statistically significant predictors of recurrence. Median duration of recurrence was 16 mo (IQR: 5-30) and there were three patients who developed an early recurrence, within two weeks of the initial procedure. The management of the recurrent prolapse was as follows: No further intervention (n = 1), repeat Delorme’s (n = 3), Altemeier’s procedure (n = 5) and rectopexy with faecal diversion (n = 3). One patient was lost during follow up.

| Variables | Values |

| Median age (yr) (IQR) | 76 (71-81.5) |

| Median ASA score (IQR) | 3 (2-3) |

| Male (n) | 2 |

| Females (n) | 38 |

| Median duration of symptoms (mo), (IQR) | 6 (3.5-12) |

| Variables | Values |

| Median length of prolapse (cm) (IQR) | 5 (5-7) |

| Median operative time (min) (IQR) | 100 (85-120) |

| Median post op stay (d) (IQR) | 4 (3-6) |

| Post op complications | Clavien-Dindo |

| 1 - 6 | |

| 2 - 1 | |

| 3 - 0 | |

| 4a - 1 | |

| Median follow up (mo) (IQR) | 6.5 (2.15-16) |

| Median duration of recurrence (mo), (IQR) | 16 (5-30) |

Rectal prolapse is a profoundly disabling condition which in Western populations occurs predominantly in elderly women. Surgery is the only way to address the pathology but the choice of operation can be influenced by patient, surgeon and disease-related factors. Traditionally abdominal rectopexy was advocated in young and fit patients and perineal procedures, including Delorme’s, were reserved for elderly individuals who are less likely to tolerate abdominal intervention. With introduction of minimally invasive laparoscopic approach many surgeons argue that abdominal rectopexy can be safely applied in most patients with better recurrence-free outcome and minimal long-term complications such as constipation. The advantage of Delorme’s procedure is that it combines minimal morbidity and shorter hospital stay with acceptable functional outcome and recurrence rate. Thus, the results of PROSPER trial, the largest randomised controlled trial comparing perineal with abdominal approaches in 293 patients, showed that there was no significant difference in recurrence rates, bowel function or quality of life between any of the treatments. Interestingly, abdominal surgery arm had the rate of recurrence much higher than previously published[6]. Delorme’s is an alternative to abdominal rectopexy not only in elderly but also in patients with a short prolapse and those wishing to avoid abdominal intervention[7]. It is therefore not surprising that perineal procedures (Delorme’s and Altemeier’s) comprise 50% to 60% of all operations performed for rectal prolapse[8]. In our series Delorme’s operation was the preferred strategy for treatment unless the length of the prolapse (more than 10 cm) necessitated its resection either perineally (Altemeier’s procedure) or abdominally (resection rectopexy). The overall recurrence rate in our cohort was 28% which may seem high in comparison with 20% based on the results of a meta-analysis[9]. Sub-group analysis of electively operated patients, following exclusion of those who had urgent surgery for irreducible prolapse, reveals a recurrence rate of 18.6%. The vast majority (80%) of our patients had no post-operative complications. The only patient who died in our cohort suffered an early recurrence and had little choice but to accept abdominal rectopexy with de-functioning sigmoid loop colostomy. She developed congestive cardiac failure and pneumonia and died on the 43rd day after the second abdominal procedure, thus confirming limited physiological reserves (ASA-3) that influenced the initial choice of perineal repair.

The best management of recurrent rectal prolapse remains uncertain[10] and there are few publications addressing this issue. A recent systematic review evaluating the results of abdominal or perineal surgery for recurrent rectal prolapse, undertaken with the aim of developing an evidence-based treatment algorithm was unable to formulate one due to the variation in surgical techniques and heterogeneity in the quality of studies[10]. Steele et al[11] advise that abdominal repair of recurrent rectal prolapse should be undertaken if the patient’s risk profile permits. In our experience the same clinical factors, i.e., lack of physiological reserves, restricted repeat surgery to perineal approach exactly as they had done at the time of the initial operation. Delorme’s procedure, however, can be safely repeated. When the length of the prolapsed bowel precluded its successful plication our preferred alternative was perineal recto-sigmoidectomy (Altemeier’s procedure) which was successfully performed in almost half of recurrences. Figure 1 outlines the algorithm we have adopted for the management of recurrent rectal prolapse after failed Delorme’s procedure. We echo the opinion of Pikarskey et al[12] that outcome of surgery for rectal prolapse is similar in cases of primary or recurrent prolapse. Early recurrence often represents a technical failure in the background of generalised pelvic floor weakness. In three of our patients it happened on day 7, 10 and 14 after Delorme’s procedure due to “cheese-wiring” of plicating sutures and the prolapsed demucosed and inflamed rectum proved particularly difficult to manage. We chose to address it by urgent laparotomy, posterior rectopexy without incorporation of synthetic mesh and formation of defunctioning loop colostomy. This was the only practical choice as the defunctioning stoma offered the benefit of faecal diversion in conditions of rectal inflammation, served as an additional point of bowel fixation anteriorly to the abdominal wall and addressed the likely faecal incontinence in the conditions of generalised pelvic floor weakness.

Our study, being retrospective observational in its design, has inevitable limitations in comparison with a randomised controlled trial. However, a randomised controlled trail aimed to answer some of the questions that have been raised in this paper such as, for example, the best treatment of early post-operative recurrence after failed Derome’s procedure may prove to be difficult, if not impossible, to set up.

Delorme’s procedure is a suitable treatment in the majority of patients with rectal prolapse regardless the age. It is an attractive choice due to low morbidity and mortality and has acceptable rate of recurrence, at least in the elective setting. The management of the recurrent rectal prolapse is often restricted to the pelvic approach by the same patient-related factors that influenced the choice of the initial operation, i.e., Delorme’s procedure. In the event of late recurrence Delorme’s procedure can be easily repeated. Long recurrent prolapse requires resection and is best addressed by perineal recto-sigmoidectomy (Altemeier’s procedure). Early recurrence developing within days or weeks often represents a technical failure that is difficult to treat and in sufficiently fit patients may require abdominal rectopexy combined with faecal diversion.

Many surgical procedures have been described for treatment of full-thickness rectal prolapse indicating that none of them is entirely satisfactory. The choice of the procedure to deal with the recurrent prolapse is even more difficult due to the absence of established consensus among surgeons.

At present there is insufficient evidence to formulate guidance on the management of the recurrent rectal prolapse as the outcome of such treatment depends on multiple patient and disease-related factors that are often beyond surgeons’ control. There is also not enough knowledge to answer the question about the best treatment of early recurrence developing in the immediate post-operative period after failed Delorme’s procedure. This study was aimed to assess the outcome of treatment of recurrent rectal prolapse after previous perineal repair (Delorme’s procedure) and, in particular, factors that influenced decision-making process. The authors also report their experience of Delorme’s procedure as a treatment of primary rectal prolapse.

This retrospective observational study challenges the view that patients with recurrent rectal prolapse after previous Delorme’s procedure can be best served with abdominal rectopexy. Despite the perceived better recurrence-free outcome of abdominal interventions the practical reality is that the vast majority of such patients cannot have abdominal rectopexy for the same patient-related reasons why it could be carried out in the first instance. This study also attempts to address the management of the difficult clinical problem of recurrence developing in the early post-operative period after failed Delorme’s procedure. In such a scenario the reported experience with urgent laparotomy and posterior suture rectopexy combined with defunctioning sigmoid loop colostomy is encouraging.

This study may assist surgeons in making decisions about the management of recurrent rectal prolapse. Future studies on the treatment of early post-operative recurrence will be of potential interest.

The term rectal prolapse refers to a full-thickness (or complete) protrusion of the rectal wall through the anus.

The authors reported their retrospective data regarding the Delorme’s procedure, which is one of the interesting topics.

P- Reviewer: Gomes A, Wang TF, Wu ZQ S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Laubert T, Bader FG, Kleemann M, Esnaashari H, Bouchard R, Hildebrand P, Schlöricke E, Bruch HP, Roblick UJ. Outcome analysis of elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic resection rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:789-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Uhlig BE, Sullivan ES. The modified Delorme operation: its place in surgical treatment for massive rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Classic articles in colonic and rectal surgery. Edmond Delorme 1847-1929. On the treatment of total prolapse of the rectum by excision of the rectal mucous membranes or recto-colic. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:544-553. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Riansuwan W, Hull TL, Bast J, Hammel JP, Church JM. Comparison of perineal operations with abdominal operations for full-thickness rectal prolapse. World J Surg. 2010;34:1116-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24849] [Article Influence: 1183.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Senapati A, Gray RG, Middleton LJ, Harding J, Hills RK, Armitage NC, Buckley L, Northover JM. PROSPER: a randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:858-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Makineni H, Thejeswi P, Rai BK. Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes after Abdominal Rectopexy and Delorme’s Procedure for Rectal Prolapse: A Prospective Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:NC04-NC07. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schoetz DJ. Evolving practice patterns in colon and rectal surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rothenhoefer S, Herrle F, Herold A, Joos A, Bussen D, Kieser M, Schiller P, Klose C, Seiler CM, Kienle P. DeloRes trial: study protocol for a randomized trial comparing two standardized surgical approaches in rectal prolapse - Delorme’s procedure versus resection rectopexy. Trials. 2012;13:155. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hotouras A, Ribas Y, Zakeri S, Bhan C, Wexner SD, Chan CL, Murphy J. A systematic review of the literature on the surgical management of recurrent rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:657-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Steele SR, Goetz LH, Minami S, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF, Parker SC. Management of recurrent rectal prolapse: surgical approach influences outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:440-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pikarsky AJ, Joo JS, Wexner SD, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Agachan F, Iroatulam A. Recurrent rectal prolapse: what is the next good option? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1273-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |