Published online Jul 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i7.501

Peer-review started: March 4, 2016

First decision: April 6, 2016

Revised: April 21, 2016

Accepted: May 10, 2016

Article in press: May 11, 2016

Published online: July 27, 2016

Processing time: 130 Days and 18.3 Hours

AIM: To compare outcomes of patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) taking aspirin for primary prophylaxis to those not taking it.

METHODS: Patients not known to have any vascular disease (coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease) who were admitted to the American University of Beirut Medical Center between 1993 and 2010 with NVUGIB were included. The frequencies of in-hospital mortality, re-bleeding, severe bleeding, need for surgery or embolization, and of a composite outcome defined as the occurrence of any of the 4 bleeding related adverse outcomes were compared between patients receiving aspirin and those on no antithrombotics. We also compared frequency of in hospital complications and length of hospital stay between the two groups.

RESULTS: Of 357 eligible patients, 94 were on aspirin and 263 patients were on no antithrombotics (control group). Patients in the aspirin group were older, the mean age was 58 years in controls and 67 years in the aspirin group (P < 0.001). Patients in the aspirin group had significantly more co-morbidities, including diabetes mellitus and hypertension [25 (27%) vs 31 (112%) and 44 (47%) vs 74 (28%) respectively, (P = 0.001)], as well as dyslipidemia [21 (22%) vs 16 (6%), P < 0.0001). Smoking was more frequent in the aspirin group [34 (41%) vs 60 (27%), P = 0.02)]. The frequencies of endoscopic therapy and surgery were similar in both groups. Patients who were on aspirin had lower in-hospital mortality rates (2.1% vs 13.7%, P = 0.002), shorter hospital stay (4.9 d vs 7 d, P = 0.01), and fewer composite outcomes (10.6% vs 24%, P = 0.01). The frequencies of in-hospital complications and re-bleeding were similar in the two groups.

CONCLUSION: Patients who present with NVUGIB while receiving aspirin for primary prophylaxis had fewer adverse outcomes. Thus aspirin may have a protective effect beyond its cardiovascular benefits.

Core tip: Aspirin is known to increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), and it is customary to stop aspirin in patients presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding. Some studies have shown that being on aspirin is associated with better outcome in those patients. Our study compared clinical outcomes in patients who presented with non-variceal UGIB while taking aspirin for primary prophylaxis only to those of patients not taking aspirin. We found that patients taking aspirin had lower mortality and shorter hospital stay than patients not taking aspirin.

- Citation: Souk KM, Tamim HM, Abu Daya HA, Rockey DC, Barada KA. Aspirin use for primary prophylaxis: Adverse outcomes in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(7): 501-507

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i7/501.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i7.501

Aspirin is being used widely in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases, and it is taken by more than 25%-33% of people older than 65 years[1]. In addition, both individual studies and meta-analysis of trials of anti-platelet therapy indicate that aspirin and other anti-platelet drugs reduce the risk of serious vascular events by approximately 25%[2].

Despite its cardiovascular protection, aspirin is associated with a 2 fold increase in risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB)[3]. However, most studies suggest that aspirin decreases mortality and hospital stay in patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB)[4,5], while some report no significant effect[6].

We recently reported that being on aspirin on presentation confers protection against mortality and morbidity in peptic disease related-UGIB[7], and in patients with NVUGIB overall[8]. We also reported that in-hospital mortality from cardiovascular causes in patients taking aspirin was similar to controls. Hence, it is not clear if the protective effect of aspirin is due to its known cardiovascular benefits. This study aims to determine if the protective effect of aspirin in NVUGIB persists in patients with no known cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease. This is done by comparing clinical outcomes in patients presenting with NVUGIB while receiving aspirin as primary prophylaxis to those who are not taking it.

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients admitted to American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) with NVUGIB between 1993 and 2010. AUBMC is a tertiary referral medical center that provides health care for around 1.5 million people in Lebanon.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of AUBMC (IM.KB.09).

In this study we included all patients who were admitted with hematemesis, coffee ground vomiting, and/or melena in the presence of an identified source of UGIB site on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[7]. We also considered patients with hematochezia to have UGIB if upper endoscopy showed a source of bleeding and colonoscopy was negative. For patients who didn’t have endoscopy, we classified patients as having UGIB if they had coffee ground emesis, hematemesis or melena.

We excluded all patients who presented with melena and/or hematochezia who had a colonic source of bleeding. Patients who met the criteria of UGIB from esophageal/gastric varices and those who had occult gastrointestinal or small bowel bleeding were excluded.

We also excluded all patients with documented history of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack (TIA), peripheral vascular disease, and those on any non-aspirin anti-platelets or anticoagulants.

Medical records of patients with signs and symptoms of UGIB were reviewed, using the ICD-9/ICD-10 coding system (codes for the following symptoms: UGIB, melena, hematochezia, hematemesis, coffee ground emesis). The data was collected from charts using a standardized data collection form. During chart review, we extracted the following information: Patient’s age, sex, comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, dyslipidemia, active systemic or gastrointestinal cancer, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation and deep vein thrombosis); mode of clinical presentation; duration of bleeding; vital signs and initial blood studies obtained upon arrival to the emergency room including complete blood count, international normalized ratio (INR), and prothrombin time; management in the emergency room and the hospital including blood transfusion. We also recorded findings on diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and the source of bleeding; type of therapeutic endoscopic procedure undertaken whenever applicable; angiography and embolization, surgical treatment and in hospital mortality. The frequency of the following outcomes were determined: In-hospital mortality, need for surgery, severe bleeding (hypotension with a systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg on admission, tachycardia with heart rate > 119 beat/min, or transfusion of more than 3 units of packed red blood cells), re-bleeding (re-bleeding after 24 h from the initial endoscopic evaluation) and therapy (recurrence of bleeding within 1 mo from discharge was also considered rebleeding), in-hospital complications including myocardial infarction, angina, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, TIA, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, skin infections, sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal failure, need for mechanical ventilation, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy; duration of hospitalization, need for blood transfusion, and number of blood units transfused were also recorded. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes included re-bleeding, severe bleeding, need for surgery or embolization, and the occurrence of any bleeding related composite outcome defined as the occurrence of any of the following: In hospital mortality, re-bleeding, severe bleeding, need for surgery or embolization[7]. We also compared in hospital complications and length of hospital stay. We divided the patients into two main groups: Those who were on aspirin upon presentation, and those who were not. We compared all the characteristics and outcomes listed above between the two groups.

Data management and analysis were carried out using the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS, version 9.1). Descriptive analyses were carried out by calculating the numbers and percent for categorical variables, and the mean and standard deviation SD for the continuous ones. Bivariate analyses were performed using the χ2 test or the independent student t-test, as appropriate.

To control for the effect of potentially confounding variables, multivariable analyses were carried out while controlling for different risk factors. For categorical outcomes multivariate logistic regression analyses were carried out where the OR, 95%CI, and P-value were reported. On the other hand, for continuous variables multivariate linear regression was carried out where the β-coefficient, 95%CI, and P-value were reported. Variables included in the regression model were those of either statistical or clinical significance. A P value < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

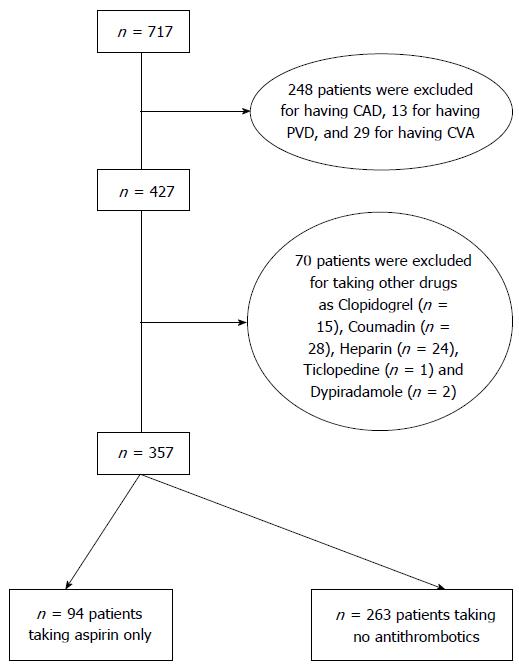

A total of 1175 patients were admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding between 1993 and 2010. Out of the 1175 patients, 717 patients had NVUGIB, of which 357 were included in this study. A total of 94 patients were on aspirin only and 263 patients were on no antithrombotics (control group, Figure 1).

The mean age was 58 years in controls and 67 years in the aspirin group (P < 0.001). Most patients were males. Patients on aspirin were more likely to have diabetes mellitus and hypertension [25 (27%) vs 31 (112%) and 44 (47%) vs 74 (28%) respectively, (P = 0.001)], as well as dyslipidemia [21 (22%) vs 16 (6%), P < 0.0001]. Smoking was more frequent in the aspirin group [34 (41%) vs 60 (27%), P = 0.02] (Table 1).

| Group | No anti-thrombotics n = 263 | Aspirin n = 94 | P value |

| Age mean (SD) | 58.4 (19.1) | 66.8 (13.1) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 169 (64.3) | 71 (75.5) | 0.05 |

| Smoking | 60 (27.0) | 34 (41.0) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 (11.8) | 25 (26.6) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 74 (28.1) | 44 (46.8) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 16 (6.1) | 21 (22.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Cancer | 55 (20.9) | 6 (6.4) | 0.001 |

| NSAIDS | 47 (17.9) | 16 (17.0) | 0.85 |

| PPI | 29 (11.0) | 4 (4.3) | 0.05 |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | 69 (26.2) | 13 (13.8) | 0.01 |

Controls had a higher prevalence of cancer (20.9% vs 6.4%, P < 0.001) and were more likely to have a history of peptic ulcer disease. The use of PPI was higher in controls [29 (11%) vs 4 (4%), P = 0.05] (Table 1). Controls also had a higher INR than patients on aspirin (Table 2).

| Group | No anti-thrombotics n = 263 | Aspirin n = 94 | P value |

| Melena | 109 (41.4) | 51 (54.3) | 0.03 |

| Hematemesis | 76 (28.9) | 17 (18.1) | 0.04 |

| Hematemesis + Melena | 46 (17.5) | 16 (17.05) | 0.92 |

| Hematochezia | 8 (3.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0.48 |

| Syncope | 33 (12.5) | 20 (21.3) | 0.04 |

| Hgb, g/L, mean (SD) | 9.2 (2.8) | 9.1 (2.4) | 0.80 |

| Hct, (%), mean (SD) | 27.4 (8.2) | 27.0 (7.1) | 0.70 |

| INR, mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.003 |

| Gastric ulcers | 40 (15.2) | 27 (28.7) | 0.004 |

| Duodenal ulcers | 65 (24.7) | 31 (33.0) | 0.12 |

| Erosive esophagitis | 31 (11.8) | 10 (10.6) | 0.76 |

| Erosive gastritis | 34 (12.9) | 38 (40.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Erosive duodenitis | 14 (5.3) | 15 (16.0) | 0.001 |

| Mallory Weiss | 18 (6.8) | 4 (4.3) | 0.37 |

| Hiatal Hernia | 24 (9.1) | 11 (11.7) | 0.47 |

| AVM | 11 (4.2) | 3 (3.2) | 0.47 |

| Cancer | 6 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.16 |

| Transfusion-unit | 4.7 (5.5) | 4.0 (3.8) | 0.25 |

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Transfusion % | 161 (61.2) | 66 (70.2) | 0.12 |

| Thermal coagulation | 25 (9.5) | 14 (14.9) | 0.15 |

| Hemostatic clips | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.54 |

| Argon-plasma coagulation | 4 (1.5) | 2 (2.1) | 0.50 |

| Angiography-embolization | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.74 |

| Surgery | 21 (8.0) | 5 (5.3) | 0.39 |

Upon presentation, patients in the aspirin group had more syncope and melena, but less hematemesis than controls [21.3% vs 12.5%, P = 0.04, 51 (54.3%) vs 109 (41.4%), P = 0.03 and 18.1% vs 28.9%, P = 0.04, respectively]. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was done on 83% of patients in the aspirin group and 71.5% of patients in the control group. The prevalence of peptic lesions found at endoscopy was higher in the aspirin group, including gastric ulcers (28.7% vs 15.2%, P = 0.004), erosive duodenitis (16% vs 5.3%, P = 0.001), and erosive gastritis (40.4% vs 12.9%, P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

The percentage of patients transfused with blood was similar in both groups, 70.2% in aspirin vs 61.2% in control (P = 0.12); and the average was 4 units of packed red blood cells per transfused patient. In both groups, the frequencies of endoscopic therapy and surgery were similar (Table 2).

After adjusting for age and comorbidities (congestive heart failure, systemic cancer, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure), patients on aspirin were less likely to die in-hospital (OR = 0.15, 95%CI: 0.03-0.64, P = 0.002), less likely to experience the composite outcome (OR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.20-0.89, P = 0.01), and tended to have a shorter hospital stay (4.9 d vs 7 d, P = 0.01) compared to controls. However, they had similar rates of in-hospital complications, re-bleeding and severe bleeding (Table 3).

| Group | No anti-thrombotics n = 263 | Aspirin n = 94 | P value | Crude OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) |

| Mortality | 36 (13.7) | 2 (2.1) | 0.002 | 0.14 (0.03-0.58) | 0.15 (0.03-0.64) |

| Hospital stay (d) | 7.0 (10.3) | 4.9 (3.5) | 0.01 | ||

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Complications-Thrombo-embolic | 3 (1.1) | 3 (3.2) | 0.19 | 2.86 (0.57- 14.41) | 4.79 (0.77-29.96) |

| Complications-infection1 | 40 (15.2) | 14 (14.9) | 0.94 | 0.98 (0.50-1.89) | 0.90 (0.45-1.81) |

| Complications-respiratory2 | 15 (5.7) | 3 (3.2) | 0.42 | 0.55 (0.15-1.93) | 0.58 (0.15-2.19) |

| Complications-myocardial infarction | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 1 | 0.93 (0.10-9.07) | 0.68 (0.07-6.79) |

| Complications-renal failure | 30 (11.4) | 9 (9.6) | 0.63 | 0.82 (0.38-1.80) | 0.68 (0.30-1.55) |

| Complications-DIC | 7 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2 | ||

| All in hospital complications | 79 (30.0) | 26 (27.7) | 0.66 | 0.89 (0.53-1.50) | 0.76 (0.43-1.32) |

| Composite outcome3 | 63 (24.0) | 10 (10.6) | 0.01 | 0.38 (0.19-0.77) | 0.42 (0.20-0.89) |

| Severe hemorrhage | 97 (36.9) | 37 (39.4) | 0.67 | 1.11 (0.69-1.80) | 1.18 (0.70-1.99) |

| Re-bleeding | 5 (5.3) | 27 (10.3) | 0.15 | 0.49 (0.18-1.32) | 0.42 (0.15-1.19) |

Because the prevalence of cancer was higher in the control group, we did a multivariate analysis in which cancer was considered a covariate rather than one of the comorbidities. The protective effect of aspirin against in hospital mortality remained unchanged.

As there were some patients who did not have endoscopy, a multivariate analysis was done on patients who had endoscopy. Regarding the mortality, it was significantly lower with aspirin group vs non aspirin OR: 0.68, 95%CI: 0.63-0.74; but this difference was not seen with severe bleeding OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.69-1.52 and rebleeding OR = 1.51, 95%CI: 0.67-3.39.

Our study suggests that patients without known vascular disease who present with NVUGIB while taking aspirin appear to have better outcomes than patients not taking any antithrombotics. Specifically, these patients had lower mortality and morbidity, and shorter hospital stay than patients not on antithrombotics.

It is known that patients who have more than one risk factor for developing vascular events are more likely to use aspirin as primary prophylaxis[9]. In this study, patients on aspirin were older and had more co-morbidity, yet they had lower mortality rates compared to controls. This occurred even though both groups had similar frequencies of therapeutic endoscopic procedures, arterial embolization and surgery making it unlikely that those contributed to the better outcome in the aspirin group. Thus, the contribution of this study is that aspirin’s beneficial effect in NVUGIB appears to extend to patients not known to have vascular disease.

It has been previously reported that patients with UGIB receiving or maintained on aspirin had improved outcomes. For example, in a randomized trial of aspirin vs placebo in patients who presented with peptic ulcer bleeding while taking aspirin, half of the deaths in the placebo group were due to non-cardiovascular causes, further suggesting that aspirin’s protective effect is not solely due to its cardiovascular benefits[10]. In two relatively large Italian prospective database studies, use of low dose aspirin upon presentation with UGIB was an independent predictor of better outcome including lower 30-d mortality[11,12]. This was true for both outpatient and inpatient NVUGIB. Furthermore, in a large pan-European retrospective cohort, it was reported that use of low or high dose aspirin was an independent predictor of lower 30 d mortality in NVUGIB[13]. Finally, in a retrospective cohort of 766 patients with UGIB due to peptic ulcers, it was reported that patients using aspirin upon presentation had a markedly decreased risk of fatal outcome (OR = 0.12, 95%CI: 0.012-0.67)[6]. Thus, the protective effect of aspirin seems to hold true for both low and high dose aspirin, and seems to cover patients with peptic ulcer related and non-peptic ulcer related NVUGIB. However, in the studies mentioned above, it was not clear whether control patients were taking other antithrombotics, and whether patients taking aspirin were using other antithrombotics concomitantly. Furthermore, in none of them was a cause of death analysis undertaken to determine how aspirin exerted its protective effect. In contrast, three studies reported no effect of aspirin on mortality in patients with UGIB. In a prospective observational study of 392 patients there was no effect of antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and/or clopidogrel) on re-bleeding, urgent surgery or mortality[14]. In another study, patients using aspirin/NSAIDs had similar mortality to those not using them. Finally, it was reported that aspirin users had lower 30-d mortality than controls among 7204 patients with peptic ulcer bleeding, but this was of borderline significance[5]. To our knowledge, there are no studies showing that aspirin increases mortality in NVUGIB.

Controls in our study had a higher prevalence of systemic cancer. In order to determine if cancer could explain, in part, the high mortality in controls, we conducted two multivariate analyses, one in which the presence of cancer was included in the composite comorbidity score, and another one in which cancer was considered a covariate. The analysis revealed that the protective effect of aspirin against in-hospital mortality remained unchanged[8].

The mechanism for the lower rate of bleeding related hospital complications and mortality is open to speculation. Aspirin is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug with inhibitory effects on cyclo-oxygenases (COX). COX inhibition has vasoconstrictive and anti-natriuretic effects, which are mediated by inhibition of prostaglandin E-2 and prostacyclin synthesis[15]. Aspirin has been reported to inhibit nitric oxide synthesis, which in turn inhibit vasodilatation[16]. By constricting the vessels in the gastrointestinal system, it may decrease the severity of NVUGIB. We recognize limitations in our study. Patients with risk factors for vascular disease were not excluded, and therefore some of our patients could have occult or latent vascular disease where aspirin protects this population against in hospital complications and mortality. The study design is not prospective or a randomized controlled trial. It is a single institution study and the sample size was small, so the applicability of the findings to other populations requires further testing. We do not have long term follow up on our patients and not all patients had endoscopy. Furthermore, the Forrest classification of bleeding lesions was not documented on all patients, which is a limitation of our study. Finally, the control group had higher INR level which may increase the risk of adverse outcomes. However, our study has several strengths. First, this is the first study to examine the effect of aspirin use as primary prophylaxis on clinical outcomes in patients with NVUGIB. Second, data collection was performed using the ICD-9 codes resulting in the identification of all the potential cases of UGIB, after which each case was reviewed individually by using well developed criteria. Finally, the study was conducted in a tertiary care referral center where all diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are standardized.

In conclusion, aspirin used for primary prophylaxis has a protective effect against adverse outcomes in patients admitted with NVUGIB, and this benefit probably extends beyond its known cardio-protective effect. Further prospective and randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these findings.

Aspirin is being widely used as primary and secondary prophylaxis for cardiovascular disease. However, aspirin use is associated with a 2 fold increase in risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB).

Most studies suggest that aspirin decreases mortality and hospital stay in patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB), while some report no significant effect. However, these studies included patients using aspirin as secondary prophylaxis.

In this study the authors compared clinical outcomes in patients that presented with NVUGIB while taking aspirin for primary prophylaxis to those of patients not taking aspirin. The authors found that the use of aspirin was associated with a better outcome, less mortality and shorter in-hospital stay.

The findings may have an impact on the practice of discontinuing aspirin in patients presenting with NVUGIB, even in those taking it for primary prophylaxis.

Aspirin use as primary prophylaxis is defined as the use of aspirin in patients with no documented cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease.

This is an interesting retrospective study comparing aspirin use with none and the outcomes of NVUGIB. The better results with aspirin use are surprising despite having patients with a poorer overall status compared to the control group.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

P- Reviewer: Ooi LLPJ, Souza JLS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Barada K, Abdul-Baki H, El Hajj II, Hashash JG, Green PH. Gastrointestinal bleeding in the setting of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:5-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4959] [Cited by in RCA: 4591] [Article Influence: 199.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hallas J, Dall M, Andries A, Andersen BS, Aalykke C, Hansen JM, Andersen M, Lassen AT. Use of single and combined antithrombotic therapy and risk of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2006;333:726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, Geraedts AA, Tijssen JG, Reitsma JB, Tytgat GN. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 5. | Mose H, Larsen M, Riis A, Johnsen SP, Thomsen RW, Sørensen HT. Thirty-day mortality after peptic ulcer bleeding in hospitalized patients receiving low-dose aspirin at time of admission. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:244-250. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Åhsberg K, Höglund P, Staël von Holstein C. Mortality from peptic ulcer bleeding: the impact of comorbidity and the use of drugs that promote bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abu Daya H, Eloubeidi M, Tamim H, Halawi H, Malli AH, Rockey DC, Barada K. Opposing effects of aspirin and anticoagulants on morbidity and mortality in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:283-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wehbeh A, Tamim HM, Abu Daya H, Abou Mrad R, Badreddine RJ, Eloubeidi MA, Rockey DC, Barada K. Aspirin Has a Protective Effect Against Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2077-2087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pearson TA, Palaniappan LP, Artinian NT, Carnethon MR, Criqui MH, Daniels SR, Fonarow GC, Fortmann SP, Franklin BA, Galloway JM. American Heart Association Guide for Improving Cardiovascular Health at the Community Level, 2013 update: a scientific statement for public health practitioners, healthcare providers, and health policy makers. Circulation. 2013;127:1730-1753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, Wu JC, Lee YT, Chiu PW, Leung VK, Wong VW, Chan FK. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Marmo R, Koch M, Cipolletta L, Capurso L, Grossi E, Cestari R, Bianco MA, Pandolfo N, Dezi A, Casetti T. Predicting mortality in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeders: validation of the Italian PNED Score and Prospective Comparison with the Rockall Score. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1284-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rotondano G, Cipolletta L, Koch M, Bianco MA, Grossi E, Marmo R. Predictors of favourable outcome in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: implications for early discharge? Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lanas A, Aabakken L, Fonseca J, Mungan ZA, Papatheodoridis GV, Piessevaux H, Cipolletta L, Nuevo J, Tafalla M. Clinical predictors of poor outcomes among patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Europe. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1225-1233. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ortiz V, Ortuño J, Rodríguez-Soler M, Iborra M, Garrigues V, Ponce J. Outcome of non-variceal acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with antithrombotic therapy. Digestion. 2009;80:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Messerli FH. Aspirin: a novel antihypertensive drug? Or two birds with one stone? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:984-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Amin AR, Attur MG, Pillinger M, Abramson SB. The pleiotropic functions of aspirin: mechanisms of action. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |