Published online Jul 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i7.476

Peer-review started: January 27, 2016

First decision: March 23, 2016

Revised: April 20, 2016

Accepted: May 10, 2016

Article in press: May 11, 2016

Published online: July 27, 2016

Processing time: 166 Days and 12.6 Hours

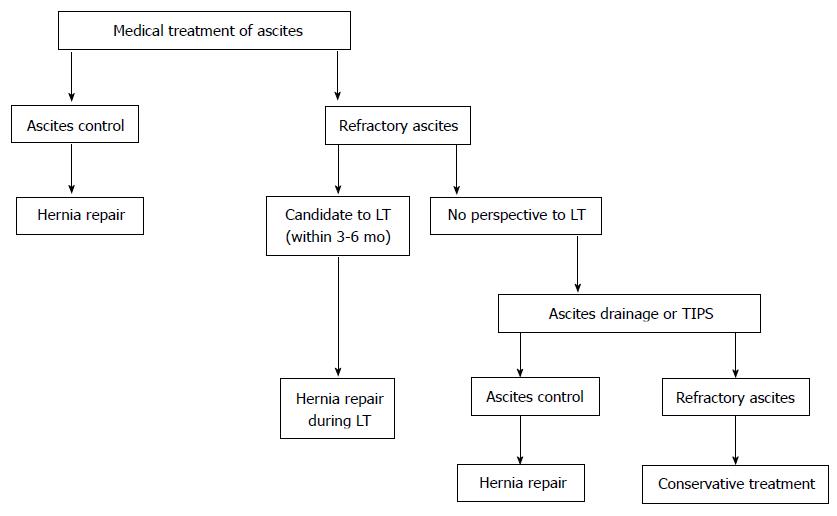

Umbilical hernia occurs in 20% of the patients with liver cirrhosis complicated with ascites. Due to the enormous intraabdominal pressure secondary to the ascites, umbilical hernia in these patients has a tendency to enlarge rapidly and to complicate. The treatment of umbilical hernia in these patients is a surgical challenge. Ascites control is the mainstay to reduce hernia recurrence and postoperative complications, such as wound infection, evisceration, ascites drainage, and peritonitis. Intermittent paracentesis, temporary peritoneal dialysis catheter or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt may be necessary to control ascites. Hernia repair is indicated in patients in whom medical treatment is effective in controlling ascites. Patients who have a good perspective to be transplanted within 3-6 mo, herniorrhaphy should be performed during transplantation. Hernia repair with mesh is associated with lower recurrence rate, but with higher surgical site infection when compared to hernia correction with conventional fascial suture. There is no consensus on the best abdominal wall layer in which the mesh should be placed: Onlay, sublay, or underlay. Many studies have demonstrated several advantages of the laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients compared with open surgical treatment.

Core tip: Umbilical hernia management in cirrhotics is controversial. Indication, timing, and surgical options of herniorrhaphy such as mesh use and laparoscopic access in these patients remain controversial. This comprehensive review shows that umbilical hernia prevalence is very high in cirrhotic patients with ascites. The etiopathogenesis of umbilical hernia in these patients is discussed in detail. Umbilical hernia management changed markedly in the last decades due to better medical care of cirrhotic patients. Ascites control is the mainstay to avoid surgical complications and recurrence.

- Citation: Coelho JCU, Claus CMP, Campos ACL, Costa MAR, Blum C. Umbilical hernia in patients with liver cirrhosis: A surgical challenge. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(7): 476-482

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i7/476.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i7.476

Umbilical hernia is a common condition, with a prevalence of 2% in the general adult population[1]. Hernia incidence in cirrhotics with ascites is 20%[2,3]. Umbilical hernia in these patients has a tendency to enlarge quickly and become symptomatic[4]. Unlike the general population, in which female sex and obesity are risk factors for umbilical hernia, cirrhotic patients who form umbilical hernias are more likely to be men with ascites[2-4].

The treatment of cirrhotic patients with umbilical hernia is controversial[5-8]. In the past, these patients were usually treated expectantly due to the elevated rate of complication and hernia recurrence[5,6]. Nonetheless, expectant management may lead to severe complications, such as hernia incarceration and necrosis and perforation of the overlying skin followed by evisceration, ascites drainage, and peritonitis[7,8]. Many recent studies showed that the results of surgical repair depend on the presence of ascites and liver function grade[9-12]. Elective umbilical herniorrhaphy is safe and effective in most cirrhotic patients in which ascites is adequately controlled[12]. However, it should be avoided in patients in which ascites is not controlled.

At present, there is no high-quality prospective randomized study on management of cirrhotic patients with umbilical hernia to guide decision-making[4]. Indication, timing, and technical aspects of herniorrhaphy in these patients remain controversial[6-10]. Use of mesh and laparoscopic access is also subject to debate[13-15]. Our objective in the present article is to review the management of cirrhotic patients with umbilical hernia, including the indications and results of the surgical treatment. Use of mesh and the laparoscopic access employed in the surgical repair is also reviewed.

Umbilical hernia is the third most common abdominal hernia in the general population, after inguinal hernia and incisional hernia[1]. In cirrhotic patients, the prevalence of umbilical hernia is higher[16]. Nearly 20% of cirrhotic patients with ascites have umbilical hernia[2,3]. Prevalence of inguinal hernias is relatively unaffected by ascites[6].

Umbilical hernia etiology in cirrhotics is multifactorial[3-5]. Elevated abdominal pressure secondary to ascites may initiate protrusion of abdominal content through a potential defect at umbilicus[15]. Ascites is possibly the major etiologic factor[6-10]. In cirrhotics, umbilical hernias occur almost exclusively in patients with persistent ascites[11-14]. In addition to increase intra-abdominal pressure, ascites correlates with liver dysfunction. Other important contributory factor is abdominal wall muscle weakness due to hypoalbuminemia and recanalization, dilation and varices formation of the umbilical vein at the umbilicus as a result of portal hypertension[16,17].

In the general population with no co-morbidites, acquired umbilical hernia increases in size very slowly[1]. On the contrary, in individuals with intraabdominal pressure elevated, such as in cirrhotic patients with ascites, umbilical hernia size increases rapidly[6,16]. In addition, ascites is also important in the development of complications in these patients. Ascites may precipitate hernia incarceration of intestine or omentum into the dense fibrous ring at the neck of the hernia[17-20]. Enormous increase of intraabdominal pressure secondary to tense ascites may also cause pressure necrosis and perforation of the overlying skin followed by evisceration, ascites drainage, and peritonitis[19,21].

Elective umbilical herniorrhaphy in the general population is the standard treatment[1]. Hernia repair in individuals with no co-morbidities is an operation associated with low complication rate[9]. On the contrary, umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients may cause expressive morbidity, such as wound infection and dehiscence, ascitic drainage through the incision, peritonitis, liver failure, and hernia recurrence[9,10]. Furthermore, presence of umbilical hernia reduces the quality of life[22].

Historically, cirrhotic patients who were subjected to umbilical herniorrhaphy had elevated morbidity and mortality rates that correlated with the severity of liver dysfunction[9,10,16]. The potential complications include decompensation of liver disease, hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatopulmonary syndrome, infection, and high hernia recurrence rate[7,8]. Therefore, in the past, surgeons avoided to perform elective umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients despite the operation simplicity[9,23-26].

Umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotics was performed only in patients with hernia complications. Conservative management was the initial option. Nonetheless, expectant management is associated with elevated rate of complications, such as hernia incarceration, evisceration, ascites drainage, and peritonitis[2,18,21]. Morbidity and mortality are high when umbilical hernia repair is performed on these patients[2,18,27,28].

With improvement in the medical care of cirrhotic patients in the last decades, some studies have showed a significant reduction of umbilical herniorrhaphy complications in these patients[4,6,23]. Marsman et al[7] have compared elective surgical repair (n = 17) with expectant treatment (n = 13) in cirrhotic patients with umbilical hernia and ascites. The authors reported that expectant treatment was associated with elevated morbidity and mortality[7]. Hospital admission for hernia incarceration was observed in 10 of 13 patients (77%), of which 6 needed emergency herniorrhaphy[7]. Two patients (15%) who were subjected to expectant treatment died from hernia complications. Conversely, no complications or hernia recurrence was recorded in 12 of 17 patients (71%) who underwent elective herniorrhaphy.

Other studies have also describe superior results and have suggested elective umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients in order to avoid complications associated with conservative management[5,8,9].

Indications and the optimal timing to repair an umbilical hernia in cirrhotic patients remain controversial. Several studies have demonstrated that umbilical hernia repair outcomes in cirrhotics depend on the presence of ascites and liver function grade[6,8]. Child’s classification and MELD score have been employed to determine the surgical risk[29-31]. Some other adverse predictors include esophageal varices, age older than 65 years, and albumin level lower than 3.0 g/dL[10].

Most studies have demonstrated that effective treatment of ascites is the essential for umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients[5,7]. In addition, effective ascites control also reduces complications, such as wound infection, evisceration, ascites drainage from the wound, and peritonitis[6].

Medical treatment of ascites with sodium restriction, diuretics, and paracentesis should be the first step in the management. In patients with no significant co-morbidities in whom medical treatment is effective in controlling the ascites, umbilical hernia repair is indicated[6].

If medical treatment fails, ascites drainage or shunting is indicated either before or at hernia correction[7-9]. Presently, intermittent paracentesis, temporary peritoneal dialysis catheter or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) may be employed. These procedures significantly reduce the incidence of hernia recurrence and wound dehiscence[23,32].

Slakey et al[32] suggested that the insertion of temporary peritoneal dialysis catheter at the end of umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients was effective in controlling ascites and reducing the complication rate. This approach has some advantages, such as outpatient care during the postoperative period and easy removal of the catheter[32]. However, peritoneal catheters are associated with a high risk of bacterial infections, which significantly increase mortality and should be discouraged[33].

In a survey performed recently with members of the Canadian Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Society, the preferred choice to ascites treatment in these patients was the use of temporary peritoneal dialysis catheter until wound healing was completed[23]. However, others reported that preoperative TIPS was preferable[27].

Rapid preoperative ascites drainage, either by paracentesis or peritoneal dialysis catheter ascites, is not a risk free procedure, and may cause strangulation of the hernia[10,23,27]. Therefore, it is recommended that ascites drainage should be gradual. Other shuntings, such as portocaval shunt and peritoneovenous shunt, are rarely employed at present. In patients in whom the shunt is effective, surgical treatment of umbilical hernia can be safely performed in most cases[4,34].

In patients in whom ascites control is ineffective, the best alternative is to repair the hernia during the transplant operation, if the patient is on the waiting list for liver transplant[16,35]. Otherwise, surgical repair should not be recommended. Based on literature data, an algorithm for the management of cirrhotic patients with umbilical and ascites is shown in Figure 1.

Liver transplant candidates may underwent umbilical herniorrhaphy during the transplant operation. Patients who have a good perspective to be transplanted within 3-6 mo, herniorrhaphy should be done during transplantation[7]. Postponement of hernia correction is not advisable due to the risk of post-transplant intestinal strangulation of an uncorrected umbilical hernia[6,7,16]. Pressure bandage should be applied carefully on the hernia until transplantation to avoid complications[16].

Some patients with patent large umbilical vein who underwent umbilical hernia repair may need emergency liver transplantation due to acute liver failure[16]. Ligation of a large patent umbilical vein during hernia repair may cause acute liver failure as a result of acute portal vein thrombosis or embolization[16,25].

The umbilical hernia may be repaired at the end of liver transplantation either from inside the abdomen through the same incision employed for the transplantation or through an additional para-umbilical incision[16]. In a retrospective study, de Goede et al[16] reported the only study of the literature comparing the two incisions. The recurrence hernia rate was higher in the same incision group than in the separate incision group (40% vs 6%)[16]. The number of patients was small in this retrospective study to allow recommendations. At present, the decision of which incision should be used for umbilical hernia repair during liver transplantation is based on the surgeon’s experience[7,16].

The rate of complications is high in cirrhotic patients with umbilical hernia and ascites, mainly due to the enormous intraabdominal pressure that enlarges the hernia rapidly[7]. These complications include infection, incarceration, strangulation, and rupture. Non-operative management of these complications is associated with elevated morbidity and mortality[2,7,18,23]. The mortality rate ranges from 60% to 80% following conservative management of ruptured umbilical hernia and 6% to 20% after urgent herniorrhaphy[2,23]. Therefore, complicated umbilical hernia in cirrhotics with ascites should be corrected urgently[2,23].

Initially, the patient should be subjected to appropriate resuscitation with intravenous fluids and antibiotics to prevent or treat ascitic fluid infection[2]. Sterile dressing is indicated in patients with ascitic fluid drainage or cutaneous infection. After patient stabilization, umbilical herniorrhaphy should be done with sutures[2,18]. Mesh should be avoided to decrease the risk of infection[2,18]. Ascites control is important to reduce complications and hernia recurrence[7-9].

As a result of elevated recurrence rate following the correction of abdominal hernias, including umbilical hernia, in cirrhotic patients, prosthetic mesh repair has been introduced and revolutionized hernia surgery[13,36]. Hernia repair with mesh compared with suture repair reduces hernia recurrence rate, but increases the risk of some complications, including infection, seroma, mesh erosion, and intestinal adhesion, obstruction, and fistula[36-38].

Several studies have demonstrated that elective mesh umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients with ascites is simple, safe, effective, and reduce hernia recurrence markedly[4,7,12]. However, many surgeons are still reluctant to employ mesh for hernia correction in these patients because of the risk of wound complications[12,23]. A significant complication in this group of patients is ascites leakage through the wound, which elevates the possibility of wound and mesh infection, followed by need of mesh removal[36].

In a recent randomized study, 80 cirrhotic patients subjected to umbilical hernia repair were divided into two groups, with a follow-up of 6 to 28 mo[4]. Hernia recurrence rate was lower in the group in which polypropylene mesh was used compared to the group without mesh in which the hernia correction was performed by conventional fascial suture (14.2% vs 2.7%)[4]. In this study, surgical site infection was more likely to occur in the mesh group than in the group without mesh, even though no patient needed mesh removal[2]. No mesh exposure or fistulas were observed in this series.

Techniques of mesh placement include onlay, inlay, sublay, and underlay[36,38]. In the onlay repair, the mesh is sutured on external oblique fascia, after dissection of the subcutaneous tissue and closing of the fascia[36]. In the inlay technique, the mesh is placed in the hernia defect and sutured circumferentially to the edges of the fascia[36]. In the sublay procedure, the mesh is inserted in the preperitoneal space or retro-rectus[36]. In the underlay procedure, the mesh is placed intraperitoneally and fixed to the abdominal wall, usually with tackers[36].

The risks of complications are related to the space in which the mesh is placed[36]. In the onlay technique, wound complications are more frequent, such as seroma, hematoma, ascites drainage, and infection of the surgical incision and mesh. This is due to the extensive detachment of subcutaneous tissue from the fascia, which typically creates a dead space between the mesh fixed on the fascia and the subcutaneous tissue. At present, inlay repair is used only occasionally due to high wound infection and recurrence rates[36].

Wound complications are less common in the sublay and underlay mesh repair techniques because the mesh lies quite deep in the preperitoneal space and intraperitoenally respectively and therefore distant from the subcutaneous tissue and skin[13,36-38]. In the underlay technique, the mesh is in contact with abdominal contents and therefore is subjected to complications, such as intestine adhesion, obstruction, erosion, and fistula[12,13,36,39]. For open surgery, the best abdominal wall layer to place the mesh is still controversial[3,12,14,36]. For laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy, the mesh is routinely inserted intraperitoneally and fixed to the abdominal wall[13,37,38].

At present, countless types and brands of mesh for hernia repair are available. They may be absorbable and permanent synthetic meshes, allograft material, and xenograft material. There is no consensus on the best mesh[12-14,36,37]. The selection is based on several aspects, including type of hernia, presence of infection, location or space of mesh placement, cost and surgeons’s preference. The most common mesh used in onlay, inlay, and sublay techniques is the polypropylene mesh[13,37,38]. For intraperitoneal mesh placement (underlay technique), synthetic meshes with different coatings or composite meshes are preferred in order to avoid intestine adherence, occlusion, and fistula[12,14,38].

The first laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy was described by Sarit et al[3] in 2003 in a patient with liver cirrhosis complicated with strangulated hernia. Several studies have documented the advantages of the less invasive laparoscopic access compared with the open surgical approach to treat umbilical hernia in cirrhotic patients[13,15,37]. The laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy is a minimally invasive and tension-free procedure in which a mesh is placed and fixed into the abdominal wall to close the inlet of the hernia[21,40].

By minimizing the access incision, the laparoscopic approach reduces postoperative pain, recovery time, and morbidity[15]. Advantages of laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotics with ascites compared to open surgical treatment are shown in Table 1.

| Minimally invasive |

| Tension free repair |

| Minimal ascites leakage through the wound |

| Less damage to the large collateral veins |

| Restricts electrolyte and protein loss due to non-exposure of viscera |

| Reduced blood loss |

| Decreased pain |

| Better aesthetics |

| Early recovery |

| Reduced hernia recurrence |

One possible disadvantage of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy is the higher cost, mainly of the equipment and material[23,37,38,41,42]. As mentioned earlier, expansive synthetic meshes with different coatings or composite meshes are needed for laparoscopic hernia repair in order to avoid intestine adherence, occlusion, and fistula. Although, several studies have demonstrated higher costs of laparoscopic abdominal hernia repair, there is no specific study on cost associated with laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients[3,39,41,42]. Considering the postoperative advantages of laparoscopic approach, additional studies are essential to establish the cost-effectiveness of umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotics[23,40].

The laparoscopic approach has been also used for complicated umbilical hernia in cirrhotics. Sarit et al[3] performed laparoscopic repair for a strangulated umbilical hernia with refractory ascites successfully by releasing the incarcerated bowel loops and fixing a mesh.

Some technical details are important to be observed at laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients with ascites in order to avoid complications. Oblique insertion of trocars into abdominal wall may avoid postoperative ascitic fistula[3]. Angulation of trocar insertion allows the layers of the abdominal wall to overlap and obstruct potential ascitic drainage. Veres’s needle and trocar must be inserted carefully in the left subcostal region to avoid lesion of an enlarged spleen secondary to portal hypertension. In order to decrease the risk of hemorrhage, reduction of incarcerated umbilical hernia contents should be performed meticulously due to the proximity and adherence of umbilical varices[17].

Umbilical hernia recurrence rate in cirrhotics with ascites ranges from 0% to 40%[3,4,6,7]. Effective ascites management is essential to achieve umbilical hernia repair success as well as to reduce recurrence rate. In a recent literature review, McKay et al[23] identified only 3 retrospective studies comparing the hernia recurrence in cirrhotic patients with ascites control and without control. When the data of these studies were grouped in a meta-analysis evaluation, the recurrence rate was 45% (22 of 49 patients) in the ascites uncontrolled group and 4% (2 of 47 patients) in the controlled group. The authors concluded that uncontrolled ascites strongly correlates with umbilical hernia recurrence in cirrhotic patients[7,23].

Several studies have reported lower umbilical hernia recurrence following hernia repair with mesh than repair without mesh in cirrhotic patients with ascites[3,4]. In a randomized study with 80 cirrhotic patients who were subjected to umbilical hernia repair, Ammar[4] reported recurrence rate of 2.7% after hernia repair with polypropylene mesh compared with 14.2% following hernia repair without mesh. However, the rate of wound complications, such as seroma, hematoma, and wound and mesh infection, is higher following umbilical hernia repair with mesh.

In summary, most studies have demonstrated that cirrhotic patients with ascites should have umbilical herniorrhaphy electively after ascites control[12]. When hernia complications occur, such as infection, incarceration, strangulation, and rupture, umbilical herniorrhaphy should be performed urgently. Ascites control is critical to reduce hernia recurrence and postoperative complications. For patients scheduled for liver transplantation, umbilical herniorrhaphy should be done during transplantation.

Expectant treatment of cirrhotic patients with umbilical hernia and ascites is associated with elevated rate of complications, such as incarceration, evisceration, ascites drainage and peritonitis. These complications require emergency surgical treatment, which carries expressive morbidity and mortality. Conversely, elective hernia correction may be performed with much less complications and it is therefore advocated. Ascites control is essential to reduce perioperative complications and recurrence. In candidates to liver transplantation, umbilical herniorrhaphy should be performed during transplantation, unless the patient presents with significant symptoms or hernia complication or if the perspective to be transplanted exceeds 3-6 mo. This review has major limitations due to lack of high-quality randomized studies. Most publications on umbilical hernia management in cirrhotic patients are case series or retrospective cohort studies with small number of patients. Definitive answers await large-scale prospective randomized controlled studies.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Vallejo L, Sirli R, Ximenes RO S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Cassie S, Okrainec A, Saleh F, Quereshy FS, Jackson TD. Laparoscopic versus open elective repair of primary umbilical hernias: short-term outcomes from the American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:741-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chatzizacharias NA, Bradley JA, Harper S, Butler A, Jah A, Huguet E, Praseedom RK, Allison M, Gibbs P. Successful surgical management of ruptured umbilical hernias in cirrhotic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3109-3113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sarit C, Eliezer A, Mizrahi S. Minimally invasive repair of recurrent strangulated umbilical hernia in cirrhotic patient with refractory ascites. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:621-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ammar SA. Management of complicated umbilical hernias in cirrhotic patients using permanent mesh: randomized clinical trial. Hernia. 2010;14:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Carbonell AM, Wolfe LG, DeMaria EJ. Poor outcomes in cirrhosis-associated hernia repair: a nationwide cohort study of 32,033 patients. Hernia. 2005;9:353-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Belghiti J, Durand F. Abdominal wall hernias in the setting of cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 1997;17:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marsman HA, Heisterkamp J, Halm JA, Tilanus HW, Metselaar HJ, Kazemier G. Management in patients with liver cirrhosis and an umbilical hernia. Surgery. 2007;142:372-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gray SH, Vick CC, Graham LA, Finan KR, Neumayer LA, Hawn MT. Umbilical herniorrhapy in cirrhosis: improved outcomes with elective repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:675-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Choi SB, Hong KD, Lee JS, Han HJ, Kim WB, Song TJ, Suh SO, Kim YC, Choi SY. Management of umbilical hernia complicated with liver cirrhosis: an advocate of early and elective herniorrhaphy. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:991-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cho SW, Bhayani N, Newell P, Cassera MA, Hammill CW, Wolf RF, Hansen PD. Umbilical hernia repair in patients with signs of portal hypertension: surgical outcome and predictors of mortality. Arch Surg. 2012;147:864-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Saleh F, Okrainec A, Cleary SP, Jackson TD. Management of umbilical hernias in patients with ascites: development of a nomogram to predict mortality. Am J Surg. 2015;209:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Eker HH, van Ramshorst GH, de Goede B, Tilanus HW, Metselaar HJ, de Man RA, Lange JF, Kazemier G. A prospective study on elective umbilical hernia repair in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. Surgery. 2011;150:542-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hassan AM, Salama AF, Hamdy H, Elsebae MM, Abdelaziz AM, Elzayat WA. Outcome of sublay mesh repair in non-complicated umbilical hernia with liver cirrhosis and ascites. Int J Surg. 2014;12:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gurită RE, Popa F, Bălălău C, Scăunasu RV. Umbilical hernia alloplastic dual-mesh treatment in cirrhotic patients. J Med Life. 2013;6:99-102. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Belli G, D’Agostino A, Fantini C, Cioffi L, Belli A, Russolillo N, Langella S. Laparoscopic incisional and umbilical hernia repair in cirrhotic patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:330-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de Goede B, van Kempen BJ, Polak WG, de Knegt RJ, Schouten JN, Lange JF, Tilanus HW, Metselaar HJ, Kazemier G. Umbilical hernia management during liver transplantation. Hernia. 2013;17:515-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | McAlister V. Management of umbilical hernia in patients with advanced liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:623-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kirkpatrick S, Schubert T. Umbilical hernia rupture in cirrhotics with ascites. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:762-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Krawczyk M, Mikneviciute J, Schürholz H. Incarcerated Umbilical Hernia After Colonoscopy in a Cirrhotic Patient. Am J Med. 2015;128:e13-e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hammad HT, Chennamaneni V, Ahmad DS, Esmadi M. Strangulated umbilical hernia after esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a patient with liver cirrhosis and ascites. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yu BC, Chung M, Lee G. The repair of umbilical hernia in cirrhotic patients: 18 consecutive case series in a single institute. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015;89:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Andraus W, Pinheiro RS, Lai Q, Haddad LB, Nacif LS, D’Albuquerque LA, Lerut J. Abdominal wall hernia in cirrhotic patients: emergency surgery results in higher morbidity and mortality. BMC Surg. 2015;15:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McKay A, Dixon E, Bathe O, Sutherland F. Umbilical hernia repair in the presence of cirrhosis and ascites: results of a survey and review of the literature. Hernia. 2009;13:461-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de la Peña CG, Fakih F, Marquez R, Dominguez-Adame E, Garcia F, Medina J. Umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients: a safe approach. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:415-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Reissfelder C, Radeleff B, Mehrabi A, Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Büchler MW, Schmidt J, Schemmer P. Emergency liver transplantation after umbilical hernia repair: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:4428-4430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Banu P, Popa F, Constantin VD, Bălălău C, Nistor M. Prognosis elements in surgical treatment of complicated umbilical hernia in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Med Life. 2013;6:278-282. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Telem DA, Schiano T, Divino CM. Complicated hernia presentation in patients with advanced cirrhosis and refractory ascites: management and outcome. Surgery. 2010;148:538-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Triantos CK, Kehagias I, Nikolopoulou V, Burroughs AK. Surgical repair of umbilical hernias in cirrhosis with ascites. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bhangui P, Laurent A, Amathieu R, Azoulay D. Assessment of risk for non-hepatic surgery in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2012;57:874-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Neeff H, Mariaskin D, Spangenberg HC, Hopt UT, Makowiec F. Perioperative mortality after non-hepatic general surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis: an analysis of 138 operations in the 2000s using Child and MELD scores. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Park JK, Lee SH, Yoon WJ, Lee JK, Park SC, Park BJ, Jung YJ, Kim BG, Yoon JH, Kim CY. Evaluation of hernia repair operation in Child-Turcotte-Pugh class C cirrhosis and refractory ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:377-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Slakey DP, Benz CC, Joshi S, Regenstein FG, Florman SS. Umbilical hernia repair in cirrhotic patients: utility of temporary peritoneal dialysis catheter. Am Surg. 2005;71:58-61. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Kathpalia P, Bhatia A, Robertazzi S, Ahn J, Cohen SM, Sontag S, Luke A, Durazo-Arvizu R, Pillai AA. Indwelling peritoneal catheters in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Intern Med J. 2015;45:1026-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Silva FD, Andraus W, Pinheiro RS, Arantes-Junior RM, Lemes MP, Ducatti Lde S, D’albuquerque LA. Abdominal and inguinal hernia in cirrhotic patients: what’s the best approach? Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2012;25:52-55. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Mateo R, Stapfer M, Sher L, Selby R, Genyk Y. Intraoperative umbilical herniorrhaphy during liver transplantation. Surgery. 2008;143:451-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Holihan JL, Nguyen DH, Nguyen MT, Mo J, Kao LS, Liang MK. Mesh Location in Open Ventral Hernia Repair: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2016;40:89-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Umemura A, Suto T, Sasaki A, Fujita T, Endo F, Wakabayashi G. Laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair in a cirrhotic patient with a peritoneovenous shunt. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2015;8:212-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Vorst AL, Kaoutzanis C, Carbonell AM, Franz MG. Evolution and advances in laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7:293-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fernández Lobato R, Ruiz de Adana Belbel JC, Angulo Morales F, García Septiem J, Marín Lucas FJ, Limones Esteban M. Cost-benefit analysis comparing laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repair. Cir Esp. 2014;92:553-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Silecchia G, Campanile FC, Sanchez L, Ceccarelli G, Antinori A, Ansaloni L, Olmi S, Ferrari GC, Cuccurullo D, Baccari P. Laparoscopic ventral/incisional hernia repair: updated Consensus Development Conference based guidelines [corrected]. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2463-2484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Colavita PD, Tsirline VB, Walters AL, Lincourt AE, Belyansky I, Heniford BT. Laparoscopic versus open hernia repair: outcomes and sociodemographic utilization results from the nationwide inpatient sample. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:109-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Tiwari MM, Reynoso JF, High R, Tsang AW, Oleynikov D. Safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of common laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1127-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |