Published online Jun 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.436

Peer-review started: January 31, 2016

First decision: March 23, 2016

Revised: March 26, 2016

Accepted: April 14, 2016

Article in press: April 15, 2016

Published online: June 27, 2016

Processing time: 142 Days and 19.1 Hours

AIM: To determine predictors of long term survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HC) by comparing patients surviving > 5 years with those who survived < 5 years.

METHODS: This is a retrospective study of patients with pathologically proven HC who underwent surgical resection at the Gastroenterology Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt between January 2002 and April 2013. All data of the patients were collected from the medical records. Patients were divided into two groups according to their survival: Patients surviving less than 5 years and those who survived > 5 years.

RESULTS: There were 34 (14%) long term survivors (5 year survivors) among the 243 patients. Five-year survivors were younger at diagnosis than those surviving less than 5 years (mean age, 50.47 ± 4.45 vs 54.59 ± 4.98, P = 0.001). Gender, clinical presentation, preoperative drainage, preoperative serum bilirubin, albumin and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase were similar between the two groups. The level of CA 19-9 was significantly higher in patients surviving < 5 years (395.71 ± 31.43 vs 254.06 ± 42.19, P = 0.0001). Univariate analysis demonstrated nine variables to be significantly associated with survival > 5 year, including young age (P = 0.001), serum CA19-9 (P = 0.0001), non-cirrhotic liver (P = 0.02), major hepatic resection (P = 0.001), caudate lobe resection (P = 0.006), well differentiated tumour (P = 0.03), lymph node status (0.008), R0 resection margin (P = 0.0001) and early postoperative liver cell failure (P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: Liver status, resection of caudate lobe, lymph node status, R0 resection and CA19-9 were demonstrated to be independent risk factors for long term survival.

Core tip: Hilar cholangiocarcinoma is an uncommon malignancy with a relatively poor prognosis. Surgery remains the only line of treatment offering the possibility of cure. The central location of the tumor and its close relationship to vascular structures at the hepatic hilum have resulted in a low resectability rate. Five year survivors were younger at diagnosis than those surviving less than 5 years. Major hepatic resection and caudate lobe resection achieved better R0 resection rate. Liver status, resection of caudate lobe, lymph node status, R0 resection and CA19-9 were demonstrated to be independent risk factors for long term survival.

- Citation: Abd ElWahab M, El Nakeeb A, El Hanafy E, Sultan AM, Elghawalby A, Askr W, Ali M, Abd El Gawad M, Salah T. Predictors of long term survival after hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A retrospective study of 5-year survivors. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(6): 436-443

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i6/436.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.436

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HC) is the most common type of biliary tract malignancy, arising at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts, and comprises 40% to 60% of all cholangiocarcinomas[1-3]. It is a complex and aggressive disease with a poor prognosis[2-6]. The resectability rate varies from 25% to 58% of patients who are surgically explored due to locally advanced tumour or liver metastasis. The central location of the tumor and its close relationship to vascular structures at the hepatic hilum have resulted in a low resectability rate and high morbidity and mortality[3-7].

Although the results of surgical treatment for HC were dismal, recent studies have reported improved outcomes using aggressive surgical approaches: Postoperative morbidity generally ranges from 30% to 50% and mortality is 10% or less[5-10]. However, the actual 5-year survival after radical resection of HC ranges from 10% to 28 % with the majority of studies reporting 20% or higher. The median survival after curative resection is about 19 to 35 mo[10-13].

Few studies of HC have long enough followed patients to report a survival beyond 5 years[7-10]. It has long been recognized that radical resection offers the only hope for cure and improves long term survival. Many studies have confirmed that hepatic resection combined with caudate lobe resection can achieve high rates of margin-free resection (R0) and significantly improve the overall survival[4-6,11-15].

The aim of this study was to determine variables that are predictors of long term survival after resection of HC by comparing patients surviving 5 years after resection of HC with those who survived less than 5 years.

This is a retrospective study of patients with pathologically proven HC who underwent surgical resection at the Gastroenterology Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt between January 2002 and April 2013. Data were collected from the patient records in April 2015. Follow-up was held regularly at the outpatient clinic. The patients were treated in accordance with the center policy, with patients with liver metastasis, lymph node metastasis far beyond regional lymph nodes, and local invasion of the major vessels of the contralateral site considered to have an unresectable tumour.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients after a careful explanation of the nature of the disease and possible treatment with its complications. The study was approved by the Institution Review Board.

Patients were divided into two groups according to their survival: Patients who survived < 5 years and those surviving > 5 years.

All patients underwent full laboratory investigations, abdominal constrast enhanced CT and/or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy was performed routinely to exclude esophageal and fundic varices. Preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) was done by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or by ultrasound (US) guided percutaneous transhepatic drainage to improve the general condition of the patients before surgery especially if there was cholangitis. The state of the liver and the extent of cirrhosis were assessed by the modified Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification[16].

Exploration was done through a bilateral subcostal incision with midline extension of the incision in some cases. Evaluation of the tumour, liver condition and the extent of lymphatic spread were done at first. The choice of surgical procedure depended on tumour extension and the general condition of patients. The tumours extension was classified according to the Bismuth-Corlette classification system[17]. All hepatobilliary resections were performed with the intent of achieving free safety margin (R0). Proximal and distal margins were assessed on frozen sections during the operation in some cases. If safety margin was proved to be positive, addition hepatobiliary resection was done as far as technically feasible until R0 was obtained if possible.

All cases underwent extrahepatic biliary resection and lymphadenectomy of locoregional lymph nodes starting from the celiac trunk up to the hilum en bloc with the mass. Hepatic resection was variable from minor resection, which included three or less segments to major resection, which included four or more segments according to Couinaud nomenclature. Hepatic resection was done using a harmonic scalpel with or without Pringle’s maneuver to control bleeding. Biliary anastomosis was done by hepaticojejunostomy with or without stenting.

Localized resection (minimal central hepatectomy segment 4) was performed in patients with type I HC without any evidence of hepatic infiltration, lymph node metastases, cirrhotic liver, or poor general condition. Hemihepatectomy was selected in cases of single lobe atrophy, invasion of the portal or hepatic branches or extension of the tumor up to the parenchyma of that lobe. Caudate lobe resection was also done in the majority of cases within the last five years.

After surgery, patients were admitted to the intensive care unit in the early postoperative days to receive the usual postoperative care by the same surgical team.

Liver function tests were performed in the postoperative period regularly on the first, third day and on the day of discharge. Abdominal ultrasonography was done routinely in all patients and repeated when there were complications. Tube drainage was carried out in cases of any significant abdominal collections.

All pathological reports were reviewed to determine the extent of the tumour, differentiation, lymph node infiltration and positive resection margin. R0 resection was defined as cases in which no gross or microscopic tumour residue was left behind, R1 resections had microscopically positive margins and R2 resections still contained some gross tumor matter[18]. Hospital mortality was defined as death during the first 30 postoperative days.

Follow-up was done in the outpatient clinic at 1 mo, 6 mo, and then every year. Clinical examinations, routine laboratory investigations (complete liver function, complete blood picture and tumour markers CEA and CA 19-9), abdominal sonography and CT scans were done at each visit.

Preoperative clinical data, intraoperative and postoperative data were collected. Postoperative complications, survival rates and recurrence rates were recorded.

Statistical analyses of the data in this study were performed with SPSS software, version 17 (Chicago, IL, United States). Descriptive data are expressed as the mean with standard deviation. Categorical variables are described using frequency distributions. Independent sample t test was used to detect differences in the means of continuous variables and χ2 test was used in cases with low expected frequencies. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Variables with P < 0.05 were entered into the Cox regression model to determine independent factors for 5-year survival. The independent factors are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with their 95%CIs. Survival curves were done using Kaplan-Meier method and differences in survival curves were compared by a Cox-regression analysis.

Between January 2002 and April 2013, surgical interventions with curative intent were performed on 278 patients who had HC. Eventually, 243 patients underwent hepatobiliary resection and 35 did not undergo any resection because of advanced disease (liver metastasis in 11 cases and local vascular infiltration in 24 cases). Of these, 34 (14%) patients were long term survivors (> 5 years) and 209 (86%) were short term survivors (< 5 years). In this study, the 1, 3 and 5 year survival rates were 53%, 35% and 22%, respectively, and the median survival was 24 mo.

Five-year survivors were younger at diagnosis than those surviving less than 5 years (mean age, 50.47 ± 4.45 vs 54.59 ± 4.98, P = 0.001). Gender, clinical presentation, preoperative drainage, preoperative serum bilirubin, albumin and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase were similar between the two groups. The level of CA19-9 was significantly higher in patients surviving < 5 years (395.71 ± 31.43 vs 254.06 ± 42.19, P = 0.0001) (Table 1).

| < 5-yr survival (n = 209) | > 5-yr survival (n = 34) | P value | |

| Age | 54.59 ± 4.98 | 50.47 ± 4.45 | 0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 124 (59.3) | 23 (67.6) | 0.09 |

| Female | 85 (40.7) | 11 (32.4) | |

| Symptoms | |||

| Pain | 73 (34.9) | 12 (35.3) | 0.97 |

| Jaundice | 206 (98.6) | 34 (100) | 0.95 |

| Weight loss | 97 (46.4) | 13 (38.2) | 0.349 |

| Serum albumin | 3.7 (± 0.46) | 3.82 (± 0.31) | 0.162 |

| Total serum bilirubin | 15.29 (± 9.74) | 15.13 (± 9.41) | 0.928 |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase | 29.92 (± 41.62) | 38.74 (± 24.12) | 0.231 |

| SGPT | 97.33 (± 112.84) | 89.18 (± 52.74) | 0.68 |

| CA19-9 | 395.71 ± 31.43 | 254.06 ± 42.19 | < 0.0001 |

| HCV | 86 (41.1) | 10 (29.4) | 0.18 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 90 (43.06) | 18 (52.9) | 0.38 |

| No preoperative biliary drainage | 119 (66.94) | 16 (47.1) | |

| ERCP | 25 (11.96) | 9 (26.5) | 0.025 |

| PTD | 65 (31.1) | 9 (26.5) | 0.564 |

Intraoperative data are shown in Table 2. Major hepatectomy, including right or left hepatectomy, was carried out in 173 (71.19%) of 243 patients besides 70 (28.8%) patients who underwent localized resection. The extent of hepatic resection had a significant impact on the survival rate. Major hepatobiliary resection was performed in 30 (88.23%) patients surviving > 5 years and in 143 (68.42%) surviving < 5 years. Segment 1 resection was done in 23 (67.64%) patients surviving > 5 years and it represented a significant factor for long term survival (P = 0.006). Liver status showed a significant difference in both groups. Five-year survivors had a less cirrhotic liver than those surviving less than 5 years (P = 0.02).

| < 5-yr survival | > 5-yr survival | P value | |

| Liver status | 0.02 | ||

| Cirrhotic (n = 102) | 97 (46.41) | 5 (14.7) | |

| Non-cirrhotic (n = 141) | 112 (53.58) | 29 (85.29) | |

| Bismuth corlette classification | 0.68 | ||

| Types I and II | 63 (30.14) | 11 (32.35) | |

| Type III | 146 (69.85) | 23 (67.64) | |

| Type IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Extent of hepatic resection | |||

| Type of resection | 0.001 | ||

| Localized resection (n = 70) | 66 (31.57) | 4 (11.76) | |

| Major resection (n = 173) | 143 (68.42) | 30 (88.23) | |

| Type of major resection | 0.07 | ||

| Lt hepatectomy (n = 102) | 81 (38.75) | 21 (61.76) | |

| Rt hepatectomy (n = 71) | 62 (29.66) | 9 (26.47) | |

| Segment 1 resection | 79 (37.79) | 23 (67.64) | 0.006 |

| Number of anastomosis | 0.85 | ||

| Single | 86 (41.14) | 18 (52.9) | |

| Multiple | 123 (58.85) | 16 (47.1) | |

| Blood transfusion | 0.91 | ||

| < 3 units | 149 (71.3) | 24 (70.58) | |

| ≥ 3 units | 60 (28.7) | 10 (29.41) | |

| Operative time | 4.28 | 4.28 | 0.75 |

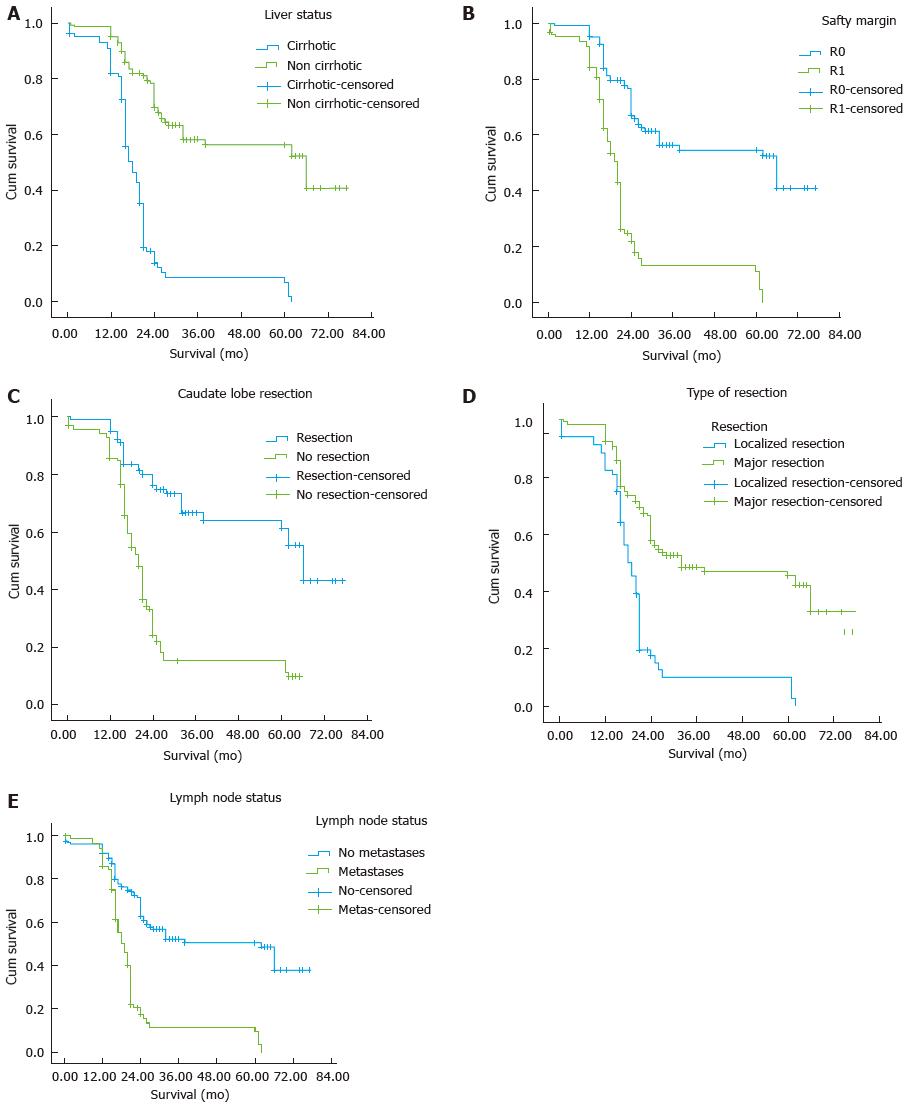

The postoperative data are shown in Table 3. Five-year survivors had well differentiated tumors than those surviving less than 5 years [18 (52.4%) vs 78 (37.32%), P = 0.033]. In addition, 5-year survivors were less likely to have positive lymph nodes [6 (17.6%) vs 81 (41.8%), P < 0.008] and positive resection margin (R1) [6 (17.6%) vs 116 (56.7%), P = 0.0001] (Figure 1).

| < 5-yr survival | > 5-yr survival | P value | |

| Hospital stay | 13 | 11.78 | 0.33 |

| Bile leakage | 75 (35.88) | 7 (20.0) | 0.08 |

| Wound infection | 50 (23.9) | 6 (17.6) | 0.39 |

| Early LCF | 38 (18.18) | 1 (2.9) | 0.023 |

| Collection | 38 (18.18) | 6 (17.6) | 0.94 |

| Bleeding and fistula | 13 (6.2) | 1 (2.9) | 0.42 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 81 (41.8) | 6 (17.6) | 0.008 |

| Histological grade | 0.033 | ||

| Well differentiated | 78 (37.32) | 20 (58.82) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 83 (39.71) | 11 (32.35) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 48 (23.0) | 3 (8.82) | |

| Safety margin | < 0.0001 | ||

| R0 | 93 (44.5%) | 28 (82.35) | |

| R1 | 116 (55.5) | 6 (17.6) | |

| Recurrence | 0.88 | ||

| Hepatic recurrence | 51 (24.4) | 8 (23.52) | |

| Local recurrence | 27 (12.9) | 6 (17.64) | |

| Late LCF | 51 (51.5) | 8 (33.3) | 0.11 |

Hepatic recurrence occurred in 51 (24.4%) patients surviving < 5 years, 40 of them (78.4%) had R1, while hepatic recurrence occurred in 8 (23.52%) patients surviving > 5 years, 4 of them (50%) had R1.

Univariate analysis demonstrated nine variables (young age, serum CA19-9, non cirrhotic liver, major hepatic resection, resection of caudate lobe, well differentiated tumour, lymph node status, R0 resection margin and early postoperative LCF) to be significantly associated with survival > 5 years. These nine factors identified in univariate analysis were further analyzed in multivariate analysis. Liver status, resection of caudate lobe, lymph node status, R0 resection and serum CA19-9 were demonstrated to be independent risk factors for long term survival (Table 4).

| Variable | P value | Oddis ratio | 95%CI for Exp (B) | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Liver status | 0.000 | 11.78 | 5.271 | 26.327 |

| Safety margin | 0.000 | 4.937 | 2.251 | 10.826 |

| Type of resection | 0.984 | 1.006 | 0.564 | 1.795 |

| Caudate lobe resection | 0.000 | 3.808 | 1.878 | 7.725 |

| Lymph node status | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.029 | 0.217 |

| Tumour differentiation | 0.265 | 0.819 | 0.577 | 1.164 |

| Age | 0.055 | 1.04 | 0.999 | 1.084 |

| Early LCF | 0.367 | 1.415 | 0.666 | 3.003 |

| CA19-9 | 0.000 | 1.01 | 1.005 | 1.015 |

Cholangiocarcinoma is an uncommon malignancy with a relatively poor prognosis, providing a major therapeutic challenge. Surgery remains the only line of treatment offering the possibility of cure, but it remains difficult because of their proximity to and possible local invasion of the portal vein, hepatic artery and the surrounding liver parenchyma and caudate lobe[4-7,19-22]. The surgical approach for HC has changed in the last two decades from primarily minor surgery to major hepatectomy with CBD resection and portal vein resection. Now all experienced hepatic surgeons agree to do hepatic resection with resection of the extrahepatic biliary tree when treating HC[20-26].

The resectability rate of HC varies in different studies from 20% to 80%. The actual 5-year survival after radical resection of HC ranges from 10 to 28% with the majority of studies reporting 20% or higher[10-15,20-26]. In this study, the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were 53%, 35% and 22%, respectively. The median survival for these cases was 24 mo. Thirty-four (14%) patients were long term survivors (> 5 years) and 209 (86%) were short term survivors (< 5 years). Five-year survivors were younger at diagnosis than those surviving less than 5 years (mean age, 50.47 ± 4.45 vs 54.59 ± 4.98, P = 0.001).

The role of PBD in the management of HC remains controversial. However, no evidence demonstrates that routine PBD facilitates resection, decreases postoperative morbidity or increases survival rate[27,28]. Although PBD does not represent a significant factor affecting long term survival, it is mandatory in cases of preoperative cholangitis or bad general condition and improves the postoperative course of patients with a serum bilirubin level > 20 mg/dL[15,26].

Curative surgery for patients with HC often necessitates hepatic resection to achieve a R0 resection and improve the long term survival because the characteristics of its growth pattern include longitudinal intraductal extension, perineural, lymphatic, and direct liver invasion[6-9,20-26]. Major hepatic resection is considered the curative treatment for HC, but it is not always safe because postoperative liver cell failure is a common cause of death after major resection in patients with compromised liver function. However, the dilemma between major hepatic resection with potential postoperative hepatic cell failure and localized resection with potential R1 and R2 resection margins might be solved by advances in preoperative and intraoperative assessments[15]. Recent advances in perioperative and operative techniques, instruments and care have led to a marked improvement in short and long term outcomes after major hepatic resection[15]. Major hepatobiliary resection for HC provides R0 resection and improves survival. In this study, 88.23% of 5-year survivors underwent major hepatic resection.

As the caudate lobe is infiltrated by HC either directly due to the close anatomic relationship or by invading the biliary branches, routine caudate lobe resection should be performed for curative treatment of HC[15,29-31]. Better R0 resection rate and long term survival have been achieved by caudate lobe resection in treating cases of HC[15,29-34]. Nimura et al[33] found that 98% of cases of caudate lobe resection were pathologically confirmed to be tumour positive in cases of HC. However, other authors showed that the caudate lobe was infiltrated by HC in 25%-40% of cases[15,33-35]. Segment 1 resection represents a significant factor affecting survival (P = 0.006) in our study. In the initial period of the study, caudate lobe resection was performed only when the caudate lobe was infiltrated, but now it is performed routinely in all cases of HC.

Safety margins after hepatic resection for cholangiocarcinoma represented a highly significant factor affecting long term survival. Many authors have reported that negative surgical margin (R0) is an important prognostic variable. R0 resection rate in the literature varies from 14% to 80 % and overall 5-year survival rate for R0 resection from 22% to 45%[4-7,15-17,26-30]. The frequency of R0 resection depends on the extent of hepatic resection. To obtain R0 resection, removal of the caudate lobe is required because of the high rate of infiltration (30%-39%)[15,29-33]. In the current study five-year survivors were less likely to have a positive safety margin [6 (17.6%) vs 116 (56.7%), P = 0.0001]. Surgical treatment of HC with localized resection has been shown to result in early recurrence after surgery due to positive surgical margins at the hepatic edge of the bile duct with low long term survival[4-8,15,26-30,32,36-40].

Lymph node metastasis was present in 20%-50% of cases of cholangiocarcinoma in the previous literature[5-12,20-25,32,35-41]. When no lymph node metastasis was detected, the 5-year survival was more than 60%. In contrast, in patients with lymph node metastasis, the 5-year survival was only 21%[25,26]. Lymph node metastasis beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament (celiac, mesenteric, or paraaortic lymph nodes) has a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival less than 12%, so it is considered a contraindication to resection.

Cirrhosis is expected to be associated with increased blood loss, need for blood transfusion and increased post-hepatectomy LCF. The treatment of HC needs careful patient selection, good perioperative assessment and care, and good decision on the extent of hepatobiliary resection. This is why to carry out the localized resection in cirrhosis and so the achievement of R0 is less in cirrhotic patients with HC[4-7,32,38-42]. In the current study, 5-year survivors had a less cirrhotic liver than those surviving less than 5 years. This result in cirrhotic patients is attributed to more aggressive HC, localized resection without caudate lobe resection, and poor liver reserve. This can explain the worse 5-year survival in cirrhotic patients in comparison to non-cirrhotic patients[5,30,39,42].

In conclusion, there were 34 (14%) 5-year survivors with resected HC in this study. Five-year survivors were younger at diagnosis than those surviving less than 5 years. The majority of long term survivors after resection of HC underwent major hepatic resection and caudate lobe resection. Well differentiated HC tumour, negative surgical margins and negative nodal metastasis have an impact on long term survival after hepatic resection for cholangiocarcinoma.

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HC) is an uncommon malignancy with a relatively poor prognosis. HC is the most common type of biliary tract malignancy, arising at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts, and comprises 40% to 60% of all cholangiocarcinomas. Surgery remains the only line of treatment offering the possibility of cure, but it remains difficult. The actual 5-year survival after radical resection of HC ranges from 10% to 28%. The median survival after curative resection is about 19 to 35 mo.

Few studies of HC have long enough followed patients to report a survival beyond 5 years. It has long been recognized that radical resection offers the only hope for cure and improves long term survival. Many studies have confirmed that hepatic resection combined with caudate lobe resection can achieve high rates of margin-free resection (R0) and significantly improve the overall survival.

The surgical approach for HC has changed in the last two decades. Now all experienced hepatic surgeons agree to do hepatic resection with resection of the extrahepatic biliary tree when treating HC. Curative surgery for patients with HC often necessitates hepatic resection to achieve a R0 resection and improve the long term survival because the characteristics of its growth pattern include longitudinal intraductal extension, perineural, lymphatic and direct liver invasion.

The data in this study suggested that major hepatobiliary resection and caudate lobe resection provide R0 resection and improve survival rate for HC. As the caudate lobe is infiltrated by HC either directly due to the close anatomic relationship or by invading the biliary branches, routine caudate lobe resection should be performed for curative treatment of HC. Furthermore, this study also provided readers with important information regarding the HC treatment and variables that increase survival rate.

HC is an uncommon malignancy with a relatively poor prognosis. HC is the most common type of biliary tract malignancy, arising at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts.

This is an interesting manuscript with a significant number of patients treating an important topic, and the aim of this study was to determine predictors of long term survival after resection of HC.

P- Reviewer: Cheon YK, Garancini M, Liu XF S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, Pisters PW, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg. 1998;228:385-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Schleck CD, Ilstrup DM. Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1993;128:871-877; discussion 877-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463-473; discussion 473-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 865] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tompkins RK, Thomas D, Wile A, Longmire WP. Prognostic factors in bile duct carcinoma: analysis of 96 cases. Ann Surg. 1981;194:447-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abdel Wahab M, Fathy O, Elghwalby N, Sultan A, Elebidy E, Abdalla T, Elshobary M, Mostafa M, Foad A, Kandeel T. Resectability and prognostic factors after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:5-10. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Launois B, Reding R, Lebeau G, Buard JL. Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: French experience in a collective survey of 552 extrahepatic bile duct cancers. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:128-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xiang S, Lau WY, Chen XP. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: controversies on the extent of surgical resection aiming at cure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:159-171. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Ardito F, Giovannini I, Aldrighetti L, Belli G, Bresadola F, Calise F, Dalla Valle R, D’Amico DF. Improvement in perioperative and long-term outcome after surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: results of an Italian multicenter analysis of 440 patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:26-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vladov N, Lukanova Ts, Takorov I, Mutafchiyski V, Vasilevski I, Sergeev S, Odisseeva E. Single centre experience with surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:299-303. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Furusawa N, Kobayashi A, Yokoyama T, Shimizu A, Motoyama H, Miyagawa S. Surgical treatment of 144 cases of hilar cholangiocarcinoma without liver-related mortality. World J Surg. 2014;38:1164-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | D’Angelica MI, Jarnagin WR, Blumgart LH. Resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: surgical treatment and long-term outcome. Surg Today. 2004;34:885-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, Oldhafer KJ, Maschek H, Tusch G, Ringe B. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer. A single-center experience. Ann Surg. 1996;224:628-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iwatsuki S, Todo S, Marsh JW, Madariaga JR, Lee RG, Dvorchik I, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumors) with hepatic resection or transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Todoroki T, Kawamoto T, Koike N, Takahashi H, Yoshida S, Kashiwagi H, Takada Y, Otsuka M, Fukao K. Radical resection of hilar bile duct carcinoma and predictors of survival. Br J Surg. 2000;87:306-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Tso WK, Lam CM, Wong J. Improved operative and survival outcomes of surgical treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1488-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5490] [Cited by in RCA: 5736] [Article Influence: 110.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:170-178. [PubMed] |

| 18. | UICC. International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. New York: Wiley-Liss 2002; . |

| 19. | Otani K, Chijiiwa K, Kai M, Ohuchida J, Nagano M, Tsuchiya K, Kondo K. Outcome of surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1033-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hirano S, Kondo S, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K, Matsumoto J, Kawasaki R. Outcome of surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a special reference to postoperative morbidity and mortality. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:455-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BS J, Youssef BA M, Klimstra D, Blumgart LH. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507-517; discussion 517-519. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Paik KY, Choi DW, Chung JC, Kang KT, Kim SB. Improved survival following right trisectionectomy with caudate lobectomy without operative mortality: surgical treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1268-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gazzaniga GM, Filauro M, Bagarolo C, Mori L. Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: an Italian experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Puhalla H, Gruenberger T, Pokorny H, Soliman T, Wrba F, Sponer U, Winkler T, Ploner M, Raderer M, Steininger R. Resection of hilar cholangiocarcinomas: pivotal prognostic factors and impact of tumor sclerosis. World J Surg. 2003;27:680-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Igami T, Nishio H, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, Nimura Y, Nagino M. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the “new era”: the Nagoya University experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:449-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lee SG, Song GW, Hwang S, Ha TY, Moon DB, Jung DH, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Kim MH, Lee SK. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the new era: the Asan experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:476-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lai EC, Mok FP, Fan ST, Lo CM, Chu KM, Liu CL, Wong J. Preoperative endoscopic drainage for malignant obstructive jaundice. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1195-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Vienne A, Hobeika E, Gouya H, Lapidus N, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Chryssostalis A, Gaudric M, Pelletier G, Buffet C. Prediction of drainage effectiveness during endoscopic stenting of malignant hilar strictures: the role of liver volume assessment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:728-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mizumoto R, Kawarada Y, Suzuki H. Surgical treatment of hilar carcinoma of the bile duct. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;162:153-158. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Abdelwahab M, El Nakeeb A, Salah T, Hamed H, Ali M, El Sorogy M, Shehta A, Ezatt H, Sultan AM, Zalata K. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma in cirrhotic liver: a case-control study. Int J Surg. 2014;12:762-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wahab MA, Sultan AM, Salah T, Fathy O, Elebidy G, Elshobary M, Shiha O, Rauf AA, Elhemaly M, El-Ghawalby N. Caudate lobe resection with major hepatectomy for central cholangiocarcinoma: is it of value? Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:321-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dinant S, Gerhards MF, Rauws EA, Busch OR, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Improved outcome of resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor). Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:872-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, Kondo S, Shionoya S. Hepatic segmentectomy with caudate lobe resection for bile duct carcinoma of the hepatic hilus. World J Surg. 1990;14:535-543; discussion 544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Dumitrascu T, Chirita D, Ionescu M, Popescu I. Resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of prognostic factors and the impact of systemic inflammation on long-term outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:913-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kawarada Y, Das BC, Naganuma T, Tabata M, Taoka H. Surgical treatment of hilar bile duct carcinoma: experience with 25 consecutive hepatectomies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:617-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tsao JI, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Hayakawa N, Kondo S, Nagino M, Miyachi M, Kanai M, Uesaka K, Oda K. Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of an American and a Japanese experience. Ann Surg. 2000;232:166-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kondo S, Hirano S, Ambo Y, Tanaka E, Okushiba S, Morikawa T, Katoh H. Forty consecutive resections of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with no postoperative mortality and no positive ductal margins: results of a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2004;240:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lai EC, Lau WY. Aggressive surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:981-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Serrablo A, Tejedor L. Outcome of surgical resection in Klatskin tumors. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wahab MA, Fathy O, Sultan AM, Salah T. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma fifteen-year experience with 243 patients at a single Egyptian center. J Solid Tumors. 2011;1:112-116. |

| 41. | Kitagawa Y, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Sano T, Yamamoto H, Hayakawa N, Nimura Y. Lymph node metastasis from hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 110 patients who underwent regional and paraaortic node dissection. Ann Surg. 2001;233:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | El Nakeeb A, Sultan AM, Salah T, El Hemaly M, Hamdy E, Salem A, Moneer A, Said R, AbuEleneen A, Abu Zeid M. Impact of cirrhosis on surgical outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7129-7137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |