Published online Jun 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.427

Peer-review started: January 11, 2016

First decision: February 2, 2016

Revised: March 21, 2016

Accepted: April 7, 2016

Article in press: April 8, 2016

Published online: June 27, 2016

Processing time: 176 Days and 15 Hours

AIM: To analyze the impact of previous cyst-enterostomy of patients underwent congenital bile duct cysts (BDC) resection.

METHODS: A multicenter European retrospective study between 1974 and 2011 were conducted by the French Surgical Association. Only Todani subtypes I and IVb were included. Diagnostic imaging studies and operative and pathology reports underwent central revision. Patients with and without a previous history of cyst-enterostomy (CE) were compared.

RESULTS: Among 243 patients with Todani types I and IVb BDC, 16 had undergone previous CE (6.5%). Patients with a prior history of CE experienced a greater incidence of preoperative cholangitis (75% vs 22.9%, P < 0.0001), had more complicated presentations (75% vs 40.5%, P = 0.007), and were more likely to have synchronous biliary cancer (31.3% vs 6.2%, P = 0.004) than patients without a prior CE. Overall morbidity (75% vs 33.5%; P < 0.0008), severe complications (43.8% vs 11.9%; P = 0.0026) and reoperation rates (37.5% vs 8.8%; P = 0.0032) were also significantly greater in patients with previous CE, and their Mayo Risk Score, during a median follow-up of 37.5 mo (range: 4-372 mo) indicated significantly more patients with fair and poor results (46.1% vs 15.6%; P = 0.0136).

CONCLUSION: This is the large series to show that previous CE is associated with poorer short- and long-term results after Todani types I and IVb BDC resection.

Core tip: Previous cyst-enterostomy is associated with more severe clinical presentation, including increased incidence of synchronous cancer, as well as poorer short- and long-term results in patients undergoing operations for Todani types I and IVb bile duct cysts.

- Citation: Ouaissi M, Kianmanesh R, Ragot E, Belghiti J, Majno P, Nuzzo G, Dubois R, Revillon Y, Cherqui D, Azoulay D, Letoublon C, Pruvot FR, Paye F, Rat P, Boudjema K, Roux A, Mabrut JY, Gigot JF. Impact of previous cyst-enterostomy on patients’ outcome following resection of bile duct cysts. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(6): 427-435

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i6/427.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.427

In contrast to Asian countries[1], congenital bile duct cysts (BDC) are rare in the United States and in Europe[2] , with an incidence between 1 in 13000 and 1 in 2 million live births[3], respectively. whereas the incidences vary from 1 in 1000 in Japan[4], to 1 in 13500 in United States[5] and 1 in 15000 in Australia[6]. For this reason, there are few published series concerning the Western experience with this disease process[7]. The optimal surgical procedure for the management of BDC is still debated with cyst-enterostomy (CE) having been preferred in the past owing to its technical simplicity[8,9]. However, CE has been reported to be associated with increased morbidity (especially biliary complications) and higher reoperation rates during short- and long-term follow-up in comparison to primary BDC resection[9-11]. Additionally, a few series have emphasized the negative impact of previous CE on results of secondary BDC resection[2]. Lastly, CE has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma[12,13]. Consequently, primary resection has been considered as the treatment of choice for BDC[9,14,15]. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the role of a previous CE on short and long-term outcomes after secondary cyst resection in a large European multicenter cohort of patients.

A multicenter retrospective study was conducted under the auspices of the Association Française de Chirurgie. During a 37 years period (between 1974 and 2011), 33 centers (including 24 academic centers) from 6 different European countries have included a total of 505 patients operated from Todani type I, IVb, II, III, IVA BDC.

The patients’ medical records were included on a website database (http://www.chirurgie-viscerale.org) using an online computerized standardized questionnaire. Patients’ demographic data, previous history of surgical and/or endoscopic interventions for hepatobiliary and pancreatic (HBP) disease, clinical symptoms, biochemical and imaging studies, details of surgical procedures, pathological data, duration of follow-up and short- and long-term postoperative outcome were collected.

Additional data were obtained from e-mail exchanges or phone calls with the referral centers. Operative reports, pathology reports and imaging studies were systematically reviewed by the 3 senior authors (Jean-Yves Mabrut, Reza Kianmanesh and Jean François Gigot) in order to establish homogeneous disease classifications. Patients’ operative risk was evaluated by using the American Society of Anesthesiology physical status score (ASA)[16]. A pediatric patient was defined as under 15 years of age.

Complicated clinical presentation was defined by the presence of severe episodes of cholangitis or pancreatitis, portal hypertension, biliary peritonitis or coexistent synchronous carcinoma. Disease involvement of the main biliary confluence (MBC) was also classified according to the classification reported by two of the co-authors[17]. Postoperative morbidity and mortality were defined at 3 mo or during hospital stay. Postoperative morbidity was graded according to Dindo-Clavien’ classification[18]. Long-term outcome was evaluated according to the dedicated evaluation score reported by the Mayo Clinic[2]. Complete cyst excision was defined as without macroscopic dilatation of bile duct after resection.

BDC subtypes were defined based on imaging studies in accordance with the Todani classification[14]. Todani BDC subtypes included type I in 47.3% (n = 239), type II in 3.7 % (n = 19), type III in 2.5% (n = 13), type IVa in 14.4% (n = 73), type IVb in 1.2% (n = 6) and type V in 30.7% (n = 155). Only patient with isolated, extrahepative BDC disease (Type I and IVb) were included (n = 245). Two additional patients that did not undergoing resection were excluded and thus 243 were ultimately analyzed.

A pediatric patient was defined as being aged under 15 years of age. Patients’ operative risk was evaluated by using the ASA[16]. Complicated clinical presentation was defined by the presence of severe episodes of cholangitis or pancreatitis, portal hypertension, biliary peritonitis or coexistent synchronous carcinoma. Disease involvement of the MBC was also classified according to the classification reported by two of the co-authors[17]. Postoperative morbidity and mortality were defined at 3 mo or during hospital stay. Postoperative morbidity was graded according to Dindo-Clavien’ classification[18]. Long-term outcome was evaluated according to the dedicated evaluation score reported by the Mayo Clinic[2].

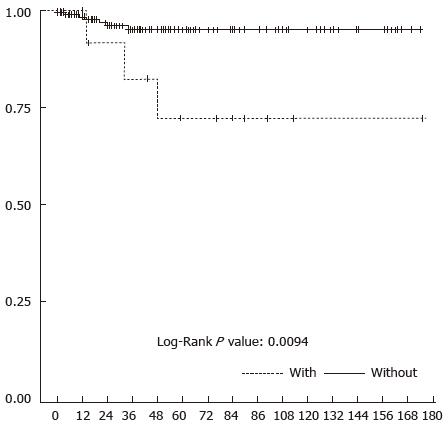

Comparisons between patient with and without CE were performed using the χ2 test (or the Fisher’s exact test when conditions for the χ2 test were not fulfilled) for categorical variables and using the Student t test (or the Mann-Whitney nonparametric rank sum test in case of non-normality) for continuous variables. Predictive factors of poor or fair result during long-term follow-up were analyzed by multivariate statistical analysis. Significant variables at the 0.15 level in univariate analysis were introduced in the multivariate logistic regression model. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to predict the postoperative survival rate at 1 year and at 3 years. The log-rank test was used to compare subgroups of patients at 1 year and at 3 years. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS® version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Patients were stratified based on a history of a previous CE. Demographic data, Todani BDC subtypes, types of imaging studies (Table 1), clinical presentations (Table 2), coexistent HBP diseases (Table 3), types of surgical procedures (Table 4), and short- and long-term postoperative outcomes (Table 5) were then compared between the two cohorts. Finally, predictive variables of poor/fair long-term outcome are reported in Table 6.

| Patient with previous CE | Patient without previous CE | Total | P value | |

| Patients | 16 | 227 | 243 | - |

| Median age (yr) at the time of BDC resection | 47.8 (26-60) | 29.2 (0-81) | 30.8 (0-81) | 0.0074 |

| Sex ratio F/M | 7 | 3.73 | 3.8 | 0.5359 |

| Adults/children | 16/0 | 148/79 | 164/79 | 0.0041 |

| ASA score1 | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 15 (93.75%) | 217 (95.6%) | 232 (95.0%) | 0.5350 |

| ≥ 3 | 1 (6.3%) | 10 (4.4%) | 11 (4.5%) | |

| Types of imaging studies | ||||

| None (incidental detection) | 1 (6.3%) | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (1.2%) | 0.1855 |

| Percutaneous ultrasound | 8 (50.0%) | 188 (82.8%) | 196 (80.7%) | 0.0042 |

| Computed tomography | 7 (43.8%) | 119 (52.4%) | 126 (51.9%) | 0.5022 |

| MR- cholangiography | 9 (56.3%) | 138 (60.8%) | 147 (60.5%) | 0.7194 |

| ERCP | 7 (43.8%) | 40 (17.6%) | 47 (19.3%) | 0.0186 |

| Endoscopic ultrasound | 8 (50.0%) | 36 (15.9%) | 44 (18.1%) | 0.0026 |

| Percutaneous cholangiography | 0 | 17 (7.5%) | 17 (7.0%) | 0.6115 |

| Intravenous cholangiography | 2 (12.5%) | 13 (5.7%) | 15 (6.2%) | 0.2583 |

| Intraoperative cholangiography | 0 | 6 (2.6%) | 6 (2.5%) | 1.0000 |

| Todani bile duct cyst types | ||||

| Type I | 16 | 221 | 237 | |

| Type IVB | 0 | 6 | 6 | 1.0000 |

| MBC adequately analyzed | 12 (75%) | 196 (86%) | 208 (85.5%) | |

| Cyst involvement of MBC | 5/12 (41.6%) | 47/196 (24.0%) | 52 (21.4%) | 0.3173 |

| MBC-1 | 3 | 39 | 42 | |

| MBC-2 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 0.2420 |

| Presence of PBM adequately explored | 10 | 180 | 190 | |

| Presence of anomalous PBM | 8 (80.0%) | 141 (78.3%) | 149 (78.4%) | 1.0000 |

| Patients with previous CE n = 16 | Patients without previous CE n = 227 | Total n = 243 | P value | |

| Median delay between symptoms and diagnosis (mo) (range) | 2 (0-486) | 2 (0-360) | 2 (0-486) | 0.8848 |

| Type of symptoms and signs | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 2 (12.5%) | 31 (13.7%) | 33 (13.6%) | 1.0000 |

| Isolated pain | 2 (12.5%) | 104 (45.8%) | 106 (43.6%) | 0.0094 |

| Cholangitis | 12 (75%) | 52 (22.9%) | 64 (26.3%) | < 0.0001 |

| Pancreatitis | 2 (12.5%) | 49 (21.6%) | 51 (21.0%) | 0.5344 |

| Abdominal mass | 2 (12.5%) | 22 (9.7%) | 24 (9.9%) | 0.6631 |

| Jaundice1 | 6 (37.5%) | 59 (26.0%) | 65 (27.2%) | 0.3843 |

| Pruritus | 1 (6.2%) | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (1.2%) | 0.1855 |

| Weight loss | 2 (12.5%) | 6 (2.6%) | 8 (3.2%) | 0.0903 |

| Complicated presentation | 12 (75%) | 92 (40.5%) | 104 (42.8%) | 0.0071 |

| Number of patients with > 2 symptoms | 9 (56.25%) | 92 (40.5%) | 102 (42.0%) | 0.2942 |

| Patients with previous CE n = 16 | Patients without previous CE n = 227 | Total n = 243 | P value | |

| Biliary disease | 9 (56.2%) | 52 (22.9%) | 61 (25.1%) | 0.0059 |

| Common biliary atresia | 0 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1.0000 |

| Stones | 4 (25%) | 37 (16.3%) | 41 (16.9%) | 0.3216 |

| Gallbladder | 0 | 16 (7.0%) | 16 (6.6%) | - |

| Cyst | 3 (18.8%) | 9 (4.0%) | 12 (4.9%) | - |

| Common bile duct | 1 (6.3%) | 22 (9.7%) | 23 (9.5%) | - |

| Intra hepatic duct | 0 | 4 (1.8%) | 4 (1.6%) | - |

| Synchronous cancer | 5 (31.3%) | 14 (6.2%) | 19 (7.8%) | 0.0043 |

| Patients with previous CE n = 16 | Patients without previous CE n = 227 | Total n = 243 | P value | |

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 2 (12.5%) | 14 (6.2%) | 16 (6.6%) | 0.2842 |

| Types of surgical procedures | ||||

| Absence of resection | 1 (6.3%) | 5 (2.2%) | 6 (2.5%) | 0.3384 |

| Elective surgery | 14 (87.5%) | 214 (94.3%) | 228 (93.8%) | 0.2583 |

| Emergency surgery | 1 (6.2%) | 9 (4.0%) | 10 (4.1%) | 0.5007 |

| Complete cyst excision | 13 (81.2%) | 199 (87.6%) | 212 (87.2%) | 0.6631 |

| Incomplete cyst excision | 2 (12.5%) | 23 (10.1%) | 25 (10.3%) | |

| Superior excision | 1 (6.3%) | 13 (5.7%) | 14 (5.8%) | |

| Inferior excision | 1 (6.3%) | 9 (4.0%) | 10 (4.1%) | - |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Associated procedures | ||||

| Hepatectomy | 2 (12.5%) | 4 (1.8%) | 6 (2.5%) | 0.0523 |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 4 (25.0%) | 4 (1.8%) | 8 (3.3%) | 0.0008 |

| Stone extraction | 2 (12.5%) | 10 (4.4%) | 12 (4.9%) | 0.2072 |

| Synchronous cancer excision | 5 (31.3%) | 13 (5.7%)1 | 18 (7.8%) | 0.0043 |

| Biliary reconstruction | ||||

| Hepatico-jejunostomy | 13 (81.2%) | 208 (91.6%) | 221 (90.9%) | 0.1658 |

| Hepatico-duodenostomy | 2 (12.5%) | 7 (3.1%) | 9 (3.7%) | 0.1116 |

| Choledoco-duodenostomy | 0 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1.0000 |

| MBC anastomosis | 8/14 (57.1%) | 96/180 (53.3%) | 104/194 (53.6%) | 0.7831 |

| Patients with previous CE n = 16 | Patients without previous CE n = 227 | Total n = 243 | P value | |

| Median postoperative hospital stay (d) (range) | 16 (9-110) | 10 (2-150) | 10 (2-150) | 0.0014 |

| Mortality rate | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1.0000 |

| Overall complications | 12 (75.0%) | 75 (33%) | 87 (35.8%) | 0.0018 |

| Grade I-II | 5 (31.3%) | 47 (20.9%) | 52 (21.4%) | 0.3454 |

| Grade III-IV | 7 (43.8%) | 28 (12.3%) | 35 (15.4%) | 0.0031 |

| Surgical complications | 7 (43.8%) | 45 (19.8%) | 52 (21.4%) | 0.0509 |

| Biliary | 0 (0.0%) | 20 (8.8%) | 20 (8.2%) | 0.3750 |

| Mixed pancreatic and biliary fistula | 1 (6.3%) | 5 (2.2%) | 6 (2.5%) | 0.3384 |

| Pancreatic | 1 (6.3%) | 17 (7.5%) | 18 (7.4%) | 1.0000 |

| Bleeding | 5 (31.3%) | 3 (1.3%) | 8 (3.3%) | < 0.0001 |

| Reoperation rate | 6 (37.5%) | 20 (8.8%) | 26 (10.7%) | 0.0032 |

| Long-term outcome of patients | ||||

| Patients with previous CE n = 13 | Patients without previous CE n = 185 | n = 198 | ||

| Median follow-up (mo) (range) | 59 (12-175) | 36 (4-372 ) | 37.5 (4-372) | 0.2482 |

| Mayo clinic score | ||||

| Excellent | 5 (38.5%) | 138 (74.6%) | 143 (72.2%) | |

| Good | 2 (15.4%) | 18 (9.7%) | 20 (10.1%) | 0.0099 |

| Fair | 0 | 5 (2.7%) | 5 (2.5%) | |

| Poor | 6 (46.2%) | 24 (13.0%) | 30 (15.1%) | |

| Mayo clinic score | ||||

| Excellent + good | 7 (53.8%) | 156 (84.3%) | 163 (82.3%) | 0.0136 |

| Fair + poor | 6 (46.2%) | 29 (15.7%) | 35 (17.7%) | |

| Covariate | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Adult patient vs child | 3.587 | 1.322-9.735 | 0.0084 | - | - | - |

| Previous cyst-enterostomy; Yes vs No | 4.611 | 1.445-14.712 | 0.0136 | 3.165 | 0.829-12.077 | 0.0918 |

| Synchronous cancer; Yes vs No | 18.462 | 4.687-72.71 | < 0.0001 | 16.612 | 3.999-69.013 | 0.0001 |

| Post-operative complications; Yes vs No | 2.397 | 1.143-5.028 | 0.0186 | - | - | - |

| Postoperative biliary complications; Yes vs No | 4.356 | 1.669-11.367 | 0.0038 | 4.597 | 1.635-12.925 | 0.0038 |

During a 37-year period (1974-2011), 243 patients underwent resections for Todani types I and IVb congenital BDC at 33 centers (including 24 academic centers). The patients’ gender ratio was largely female (193/50, i.e., 3.86%). Median age was 30.8 years old (range: 0.1-81 years) and 79 patients were classified at pediatric. Patients’ characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Sixteen patients had undergone previous CE (16/243, i.e., 6.58%), they were all adults (100% vs 65.2%; P = 0.0041) and significantly older (47.8-year-old vs 29.2-year-old; P = 0.0074) than those without a history of CE. Imaging studies used for the diagnosis of BDC were different between the 2 groups: Patients without previous history of CE were offered more non-invasive studies, whereas those patients with previous CE had been submitted to significantly more endoscopic techniques. There was no difference concerning the BDC sub-types, the MBC involvement and the presence of an anomalous pancreato-biliary malunion (PBM) (Table 1).

The median delay between the disease’s first symptoms and the diagnosis of BDC was 2 mo (0-486) and was similar between the 2 groups of patients. Abdominal pain was the most common presenting symptom (43.6%) for the whole population and significantly more frequent in patients without previous CE (12.5% vs 45.8%; P = 0.009). The group of patients with previous CE was observed to have a significantly increased prevalence of cholangitis (75.0% vs 22.9%; P < 0.0001) and complicated presentation (75.0% vs 40.5%; P = 0.007) (Table 2).

Coexistent biliary disease (liver disease, pancreatic disease, and biliary disease) occurred in 25.1% of the present cohort and was significantly more frequent in patients with previous CE (56.2% vs 22.9%; P = 0.006). The occurrence of associated calculus disease (16.9%) was similar between the two groups. Synchronous biliary cancer occurred in 7.8% of the total cohort and was significantly more frequent in patients with previous CE (31.3% vs 6.2%; P = 0.004) (Table 3).

Preoperative biliary drainage was performed in 6.6% of the whole cohort. All patients underwent surgical exploration. However, 5 adult patients without CE did not undergo BDC resection, one for no specified reason, the others respectively for locally advanced gallbladder cancer, peritoneal carcinomatosis, severe inflammation of the hepatic pedicle, performance of simple cholecystectomy. Only one patient with previous CE had severe hepatic pedicle inflammation prohibiting cyst resection. Associated bile duct stone extraction rates were similar between the two subgroups. Complete cyst excision was accomplished in 93.8% of all patients and there was no significant difference between the two groups of patients. Associated hepatectomy was more frequently performed in patients with previous CE but the difference was not significant (12.5% vs 1.8%; P = 0.0523). Associated pancreaticoduodenectomy was significantly more frequent in patients with previous CE (25% vs 1.8%; P = 0.008) (Table 4).

Postoperative death due to cardiac arrhythmia, occurred in 1 patient (0.4%). Overall morbidity and severe complications rates were 36.2% and 14%, respectively. Patients with previous CE had significantly higher morbidity rates (75.0% vs 33.5%; P < 0.0008), more severe complications (Grade III-IV) (43.8% vs 11.9%; P = 0.003), more hemorrhagic complications (31.3% vs 1.3%; P < 0.0001), a greater reoperation rate (37.5% vs 8.8%; P = 0.003) and a longer median length of stay (16 vs 10 d; P < 0.001) than those without previous CE (Table 5).

A total of 44 patients were lost for follow-up at 3 mo, only 3 of whom belonged to the subgroup of patients with previous CE. The median follow-up in the 198 remaining patients was 37.5 mo (range: 4 to 732 mo) for the whole cohort, without any difference between both subgroups. According to the dedicated Mayo Clinic Risk score evaluating long-term results, there were significantly more patients with fair and poor results in the subgroup of patients with previous CE (P = 0.001). The overall 3-year survival rate was significantly lower in patients with prior CE (82.5% vs 95.9%; P = 0.01) (Figure 1) (Table 5).

Predictive variables of poor and fair long-term results (according to the Mayo Clinic clinical score) were evaluated in the 198 patients surviving surgery and with a follow-up over 3 mo. Univariate statistical analysis indicated that predictive variables of poor or fair long-term results were to be an adult patient, with prior CE, postoperative complications, postoperative biliary complications and coexistent synchronous cancer. By multivariate analysis, predictive variables of poor or fair long-term results were previous CE, synchronous cancer and postoperative biliary complications (Table 6).

The present retrospective series shows that patients submitted to secondary resection of congenital BDC following a previous cyst-enterostomy suffered more complications before, during and after surgery with poorer results during long-term follow-up. Strengths of the present series include the relatively large cohort of patients issued from a multicentric European series, and the central revision of radiological, operative and pathological data, thereby ensuring a homogeneous classification of patients and their symptoms and signs both prior and after surgery, with the use of a dedicated clinical score for long-term results. Furthermore, the analysis was performed in a homogeneous group of BDC with only extrahepatic biliary involvement, namely patients suffering from Todani types I and IVb BDC. Indeed, patients with Todani type IVA were excluded from the present series so that poor results could not be due to residual non-resected intrahepatic biliary disease.

According to the results of the present study, primary complete excision of BDC, with the construction of a wide bilio-digestive anastomosis to a healthy proximal bile duct should be the “gold standard” surgical management of patients suffering from BDC[2,14,19]. Cyst-enterostomy must definitively be abandoned as a treatment option. Limitations of the study include its retrospective design, its long period (37 years) of patients inclusion and the number of patients without available long-term follow-up. The comparison between patients with previous cyst-enterostomy and the control group should also be considered with caution due to the small number of patients in the CE group.

However, despite cyst-enterostomy being no longer the primary approach for the surgical management of BDC, its prevalence was 17.2% in 186 patients operated on after 1980[2,7,20-22] and previous cyst-enterostomy was still observed in 7.3% of 354 patients operated on after 1990[23-26]. Practically, this means that previous CE still remains a challenge during the management of BDC.

Indeed, the consequences of having undergone a cyst-enterostomy, regardless of the technique used, easily explain the more complicated clinical presentation of previously operated patients encountered in the present series: Possible mechanisms include reflux of digestive juice through the entire biliary tract, activation of pancreatic juice by enterokinases linked to pancreatico-biliary malunion[27] or even anastomotic stricture of the CE on diseased cystic biliary tissue[19,28,29]. Any of these can lead to severe biliary inflammation[15], cholangitis, hepatolithiasis[10,19,30,31] and increase the risk of carcinogenesis[12,13,19,27]. The latter is estimated to be over 50% by Todani et al[27]. Indeed, malignant degeneration of BDC occurs more than 15 years earlier in patients with previous CE than in patients with primary carcinomas, with a median delay of 4 years in a series by Flanigan et al[13] to 10 years (range: 1-53 years of delay) in yet another by Todani et al[27] and, overall, is associated with a very poor prognosis. Finally, the reoperation rate after previous CE is high, ranging from 15.7% to 87.5%[1,9,30,32].

The present series also shows that more complex surgical procedures had to be used for patients with a previous CE, mainly due to an increased need for a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Such an extensive procedure was linked, for half of these patients, with the presence of coexistent carcinoma, thereby, requiring tumor resection with a wide tumor-free margin. The other pancreaticoduodenectomies were mainly performed because of severe inflammation within the hepatic pedicle, probably as a result of repeated episodes of cholangitis. This feature observed during secondary BDC resection in patients with previous CE has not been reported until now.

According to several surgical series which compared primary CE with primary BDC resection with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy have reported an increased mortality rate (range: 8.3%-10% vs 0%-7%), morbidity rate (range: 17%-93% vs 0%-17%) and reoperation rate (range: 29.7%-87.5% vs 0%) in patients with primary CE[9,10,30]. At the time of writing, there are only 3 studies that compared the morbidity and mortality rates between primary BDC resection and secondary BDC resection with previous CE, and these concerned series with only small numbers of patients[2,15,19]. For patients with previous CE, Chijiiwa et al[19] and Gigot et al[2] observed significantly more early postoperative complications, whilst Kaneko et al[15] reported significantly increased operative blood losses, operative time, early postoperative complications and wound infections. The present series demonstrates similar findings of an increased rate of overall and severe postoperative complications as well as hemorrhagic complications and reoperation rates for patients operated following previous CE.

The key-messages of this first large European multicenter study are that BDC patients who have undergone previous CE have more complications including carcinoma, that long-term results and survival rate are worse and that the reoperation rate is greater. It should be emphasized that these results cannot be attributed to intrahepatic disease alone as only Todani type I and IVb lesions were studied in this analysis. Late complications were also increased in the series reported by Kaneko et al[15], especially regarding late development of hepatolithiasis and pancreatic stones, though this was not reported in the series by Chijiiwa et al[19]. Finally, multivariate statistical analysis confirmed in the present series that previous CE was representing an independent predictive factor of fair or poor prognosis after secondary BDC resection. Weaknesses of the present study include its retrospective nature, the number of patients excluded from long-term follow-up after 3 mo (18.1% of the whole series), the limited median follow-up duration of 37.5 mo and the small numbers of patients with previous CE.

In conclusion, this European retrospective series showed that previous CE was associated with a more complicated presentation, more coexistent HPB diseases including synchronous cancer, more complex surgery and worse early and long-term postoperative outcomes. These features confirmed the abandonment of cyst-enterostomy for the surgical management of congenital bile duct cysts.

Jean De Ville de Goyet1, Catherine Hubert1, Jan Lerut1, Jean-Bernard Otte1, Raymond Reding1, Olivier Farges2, Alain Sauvanet2, Gilles Mentha3, Oulhaci Wassila3, Barbara Wildhaber3, Felice Giulante4, Francesco Ardito4, Maria De rose Agostino4, Thomas Gelas5, Pierre-Yves Mure5, Jacques Baulieux6, Christian Gouillat6, Ducerf Christian6, Sabine Irtan7, Sabine Sarnacki7, Alexis Laurent8, Philippe Compagnon8, Chady Salloum8, Roger Lebeau9, Olivier Risse9, Stéphanie Truant10, Emmanuel Boleslawski10, François Corfiotti10, Alexandre Doussot11, Pablo Ortega-Deballon11, Pierre Balladur12, Mustapha Adham13, Christian Partensky13, Taore Alhassane13, Catelin Tiuca Dane14, Yves-Patrice Le Treut15, Mathieu Rinaudo15, Jean Hardwigsen15, Hélène Martelli16, Frédéric Gauthier16, Sophie Branchereau16, Simon Msika17, Daniel Sommacale18, Jean-Pierre Palot 18, Ahmet Ayav19, Charles-Alexandre Laurain19, Massimo Falconi20, Denis Castaing21, Oriana Ciacio21, René Adam21, Eric Vibert 21, Roberto Troisi22, Aude Vanlander22, Stéphane Geiss23, Gilles De Taffin23, Denis Collet24, Antonio Sa Cunha24, Laurent Duguet25, Bouzid Chafik26, Kamal Bentabak26, Abdelaziz Graba26, Nicolas Meurisse27, Jacques Pirenne27, Lorenzo Capussotti28, Serena Langelle28, Nermin Halkic29, Nicolas Demartines29, Alessandra Cristaudi29, Gaëtan Molle30, Baudouin Mansvelt30, Massimo Saviano31, Gelmini Roberta31, Ousema Baraket32, Samy Bouchoucha32, Bernard Sastre33.

1Cliniques Universitaires Saint- Luc, Brussels, Belgium , 2Beaujon Hospital, Clichy, France, 3Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland, 4Gemelli University Hospital, Roma, Italy, 5Mother and Children Hospital, Lyon, France, 6La Croix-Rousse Hospital, Lyon, France, 7Necker Hospital, Paris, France, 8Henri Mondor Hospital, Creteil, France, 9Michallon Hospital, Grenoble, France, 10Claude Huriez Hospital, Lille, France, 11Dijon University Hospital, Dijon, France, 12Saint Antoine Hospital, Paris, France, 13Edouard-Herriot Hospital, Lyon, France, 14Rennes University Hospital, Rennes, France, 15Conception Hospital, Marseille, France, 16Bicetre Hospital, Paris, France, 17Louis Mourier Hospital, Colombes, France, 18Robert Debré Hospital, Reims, France, 19Nancy University Hospital, Nancy, France, 20Negrar University Hospital, Verona, Italy, 21Paul-Brousse Hospital, Paris, France, 22Amiens University Hospital, Amiens, France, 22Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium, 23Le Parc Hospital, Colmar, France, 24Bordeaux University Hospital, Bordeaux, France, 25Sainte Camille Hospital, Bry-sur-Marne, France, 26Pierre et Marie Curie Hospital, Alger, Algeria, 27UZ Leuven University Hospital, Leuven, Belgium, 28Mauriziano University Hospital, Torino, Italy, 29Vaudois University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland, 30Jolimont Hospital, La Louvière, Belgium, 31Modena University Hospital, Modena, Italy, 32Habib Boughefta Hospital, Bizertz, Tunisia, 33La Timone Hospital, Marseille, France.

The authors thank the staff and patients of all the participating hospitals for helping with the gathering of all the necessary information for this retrospective study. They are also grateful to Professor Claire Craddock-de Burbure for her meticulous reading of the manuscript.

Congenital bile duct cysts (BDC) are rare in the United States and in Europe. Cyst-enterostomy has been reported to be associated with increased morbidity (especially biliary complications) and higher reoperation rates during short- and long-term follow-up in comparison to primary BDC resection. Consequently, primary resection has been considered as the treatment of choice for BDC. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the role of a previous cyst-enterostomy (CE) on short and long-term outcomes after secondary cyst resection in a large European multicenter cohort of patients.

Limitation of the study includes its retrospective design, its long period (37 years), included patients and the number of patients without available long-term follow-up. The comparison between patients with previous cyst-enterosotmy and the comtrol group should also be considered with caution due to the small number of patients in the CE group. However, despite cyst-enterostomy being no longer the primary approach for the surgical management of BDC, its prevalence was 17.2% in 186 patients operated on after 1980 and previous cyst-enterostomy was still observed in 7.3% of 354 patients operated on after 1990. Practically, this means that previous CE still remains a challenge during the management of BDC.

This European retrospective series showed that previous CE was associated with a more complicated presentation, more coexistent HPB diseases including synchronous cancer, more complex surgery and worse early and long-term postoperative outcomes. These features confirmed the abandonment of cyst-enterostomy for the surgical management of congenital bile duct cysts.

These features confirmed the abandonment of cyst-enterostomy for the surgical management of congenital bile duct cysts.

The results of this European multicenter study are very interesting and the manuscript is well-written.

P- Reviewer: Guan YS, Kleeff J, Klinge U S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Yamaguchi M. Congenital choledochal cyst. Analysis of 1,433 patients in the Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1980;140:653-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gigot JF, Nagorney DM, Farnell MB, Moir C, Ilstrup D. Bile duct cysts: A changing spectrum of presentation. J Hep Bil Pancr Surg. 1996;3:405-411. |

| 3. | Söreide K, Körner H, Havnen J, Söreide JA. Bile duct cysts in adults. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1538-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kimura K, Tsugawa C, Ogawa K, Matsumoto Y, Yamamoto T, Kubo M, Asada S, Nishiyama S, Ito H. Choledochal cyst. Etiological considerations and surgical management in 22 cases. Arch Surg. 1978;113:159-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hays DM, Goodman GN, Snyder WH, Woolley MM. Congenital cystic dilatation of the common bile duct. Arch Surg. 1969;98:457-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jones PG, Smith ED, Clarke AM, Kent M. Choledochal cysts: experience with radical excision. J Pediatr Surg. 1971;6:112-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lenriot JP, Gigot JF, Ségol P, Fagniez PL, Fingerhut A, Adloff M. Bile duct cysts in adults: a multi-institutional retrospective study. French Associations for Surgical Research. Ann Surg. 1998;228:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Alonso-Lej F, Rever WB, Pessagno DJ. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of 2, and an analysis of 94, cases. Int Abstr Surg. 1959;108:1-30. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Flanigan PD. Biliary cysts. Ann Surg. 1975;182:635-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saing H, Tam PK, Lee JM. Surgical management of choledochal cysts: a review of 60 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:443-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Plata-Muñoz JJ, Mercado MA, Chan C, González QH, Orozco H. Complete resection of choledochal cyst with Roux-en-Y derivation vs. cyst-enterostomy as standard treatment of cystic disease of the biliary tract in the adult patient. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:13-16. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Todani T, Tabuchi K, Watanabe Y, Kobayashi T. Carcinoma arising in the wall of congenital bile duct cysts. Cancer. 1979;44:1134-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Flanigan DP. Biliary carcinoma associated with biliary cysts. Cancer. 1977;40:880-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263-269. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kaneko K, Ando H, Watanabe Y, Seo T, Harada T, Ito F, Niimi N, Nagaya M, Umeda T, Sugito T. Secondary excision of choledochal cysts after previous cyst-enterostomies. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2772-2775. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL. ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:239-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1437] [Cited by in RCA: 1474] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mabrut JY, Partensky C, Gouillat C, Baulieux J, Ducerf C, Kestens PJ, Boillot O, de la Roche E, Gigot JF. Cystic involvement of the roof of the main biliary convergence in adult patients with congenital bile duct cysts: a difficult surgical challenge. Surgery. 2007;141:187-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24803] [Article Influence: 1181.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chijiiwa K. Hazard and outcome of retreated choledochal cyst patients. Int Surg. 1993;78:204-207. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Cheng SP, Yang TL, Jeng KS, Liu CL, Lee JJ, Liu TP. Choledochal cyst in adults: aetiological considerations to intrahepatic involvement. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:964-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Durgun AV, Gorgun E, Kapan M, Ozcelik MF, Eryilmaz R. Choledochal cysts in adults and the importance of differential diagnosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:738-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lal R, Agarwal S, Shivhare R, Kumar A, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Type IV-A choledochal cysts: a challenge. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cho MJ, Hwang S, Lee YJ, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Lee SK, Kim MH, Lee SS, Park DH. Surgical experience of 204 cases of adult choledochal cyst disease over 14 years. World J Surg. 2011;35:1094-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Shah OJ, Shera AH, Zargar SA, Shah P, Robbani I, Dhar S, Khan AB. Choledochal cysts in children and adults with contrasting profiles: 11-year experience at a tertiary care center in Kashmir. World J Surg. 2009;33:2403-2411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Visser BC, Suh I, Way LW, Kang SM. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 2004;139:855-860; discussion 860-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Woon CY, Tan YM, Oei CL, Chung AY, Chow PK, Ooi LL. Adult choledochal cysts: an audit of surgical management. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:981-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Urushihara N. Carcinoma related to choledochal cysts with internal drainage operations. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:61-64. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Urushihara N, Sato Y. Reoperation for congenital choledochal cyst. Ann Surg. 1988;207:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Joseph VT. Surgical techniques and long-term results in the treatment of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:782-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Deziel DJ, Rossi RL, Munson JL, Braasch JW, Silverman ML. Management of bile duct cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 1986;121:410-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Takiff H, Stone M, Fonkalsrud EW. Choledochal cysts: results of primary surgery and need for reoperation in young patients. Am J Surg. 1985;150:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Powell CS, Sawyers JL, Reynolds VH. Management of adult choledochal cysts. Ann Surg. 1981;193:666-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |