Published online Mar 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.274

Peer-review started: August 11, 2015

First decision: October 16, 2015

Revised: December 17, 2015

Accepted: December 29, 2015

Article in press: January 4, 2016

Published online: March 27, 2016

Processing time: 226 Days and 1.3 Hours

AIM: To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis on post-operative complications after surgery for Crohn’s disease (CD) comparing biological with no therapy.

METHODS: PubMed, Medline and Embase databases were searched to identify studies comparing post-operative outcomes in CD patients receiving biological therapy and those who did not. A meta-analysis with a random-effects model was used to calculate pooled odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI) for each outcome measure of interest.

RESULTS: A total of 14 studies were included for meta-analysis, comprising a total of 5425 patients with CD 1024 (biological treatment, 4401 control group). After biological therapy there was an increased risk of total infectious complications (OR = 1.52; 95%CI: 1.14-2.03, 8 studies) and wound infection (OR = 1.73; 95%CI: 1.12-2.67; P = 0.01, 7 studies). There was no increased risk for other complications including anastomotic leak (OR = 1.19; 95%CI: 0.82-1.71; P = 0.26), abdominal sepsis (OR = 1.22; 95%CI: 0.87-1.72; P = 0.25) and re-operation (OR = 1.12; 95%CI: 0.81-1.54; P = 0.46) in patients receiving biological therapy.

CONCLUSION: Pre-operative use of anti-TNF-α therapy may increase risk of post-operative infectious complications after surgery for CD and in particular wound related infections.

Core tip: Pre-operative use of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) therapy increases risks of post-operative infectious complications after surgery for Crohn’s disease, particularly wound sepsis. Surgery should be planned carefully and ideally performed after appropriate cessation of anti-TNF-α therapy to mitigate increased post-operative risks.

- Citation: Waterland P, Athanasiou T, Patel H. Post-operative abdominal complications in Crohn’s disease in the biological era: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(3): 274-283

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i3/274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.274

The introduction of biological therapy for gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease (CD) has been a significant landmark in non-operative management of this chronic relapsing condition. The central role of the cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) in persistence of mucosal inflammation underlies the marked efficacy of monoclonal antibodies such as Infliximab and Adulimimab[1,2]. Multiple randomised clinical trials including ACCENT and CHARM have shown high clinical response (35%-50%) and maintenance rates for both infliximab and adalimumab in modest to severe CD. Eight-weekly infusion regimes appear to be most effective for patients with an initial response to the induction dose of monoclonal agent. Long term use of such agents is supported up to three years and is extremely effective as a steroid-sparing therapy[1-3]. Currently monoclonal antibodies are being utilised earlier in the treatment algorithm for moderate to severe inflammatory disease, in addition to more complex intra-abdominal fistulating disease in an attempt to achieve mucosal healing and remission. However, a significant proportion of patients do not achieve mucosal healing and eventually arrive at surgical intervention after step-up therapy (10%-20% per year of use of infliximab)[4,5]. Other indications for surgery include intolerance of therapy due to complications. Thus, surgical intervention is required in up to 50% of patients with CD within 10 years of diagnosis[6]. There are concerns as to operative intervention within the context of such potent immunosuppression due to the nature of biological therapy.

Current data reveals a contradictory picture of the adverse effects of pre-operative use of anti-TNF-α agents and postoperative complications following bowel resection. Several studies indicate an increase in septic complications; whether it be abdominal sepsis or superficial wound infections[7,8]. Other studies report no adverse impact of monoclonal antibodies on post-operative outcome[9-11]. It would be beneficial to subject study findings in a comprehensive meta-analytical framework to identify any associations. Several meta-analyses have been performed previously and have examined total or major postoperative complications after abdominal surgery in treatment and control groups[12-14]. In contrast, our analysis aims to study specific septic complications in the CD patient receiving anti-TNFα therapy to investigate postoperative risk in greater detail.

PRISMA statement guidelines were followed for conducting and reporting meta-analysis data. We searched Medline and Embase from inception to May 2015 using the search terms “infliximab” or “immunosuppressant” or “monoclonal antibody” or “Humira” or “Adalimumab” or “Remicade” and “Crohn’s disease” or “Crohn disease” and “complications” or “outcomes” or “postoperative” or “morbidity”. The identical terms were used again in PubMed. The search encompassed titles, abstracts, subject headings and registry words. Articles were limited to those published in the English language, animal studies excluded and duplicates were removed.

Studies identified from the differing searches were amalgamated and titles and abstracts were scrutinised to include relevant material only. Full text versions were obtained of eligible articles and were reviewed by both authors (PW and HP) to ensure that appropriate data was selected for analysis. Discrepancies between the authors were resolved by discussion of the particular manuscript. Studies were only included in the analysis if patients had intestinal resection with anastomosis for CD and had been administered infliximab within 90 d preceding abdominal surgery. Postoperative complication rate (30-90 d) including anastomotic leak was a compulsory outcome measure. Studies without the aforementioned data were excluded. Studies on indeterminate colitis, ulcerative colitis (UC) or ileoanal pouch were excluded.

Data were interrogated by both authors (PW and HP) and salient patient, disease and surgery-related factors were noted. The number of patients in the treatment (pre-operative anti-TNF administration) and control group (no use of pre-operative anti-TNF agent) were noted and compared for the outcomes of interest. Both groups comprised of patients with CD. Studies on mixed groups of patients with CD and UC were only included if data pertinent to CD could be extracted with a separation of patients on IFX and those on other therapy. Other conditions such as neoplasia and ileoanal pouch procedures were excluded. An attempt was made to establish severity of CD by noting the presence of pre- or intra- operative abscess and use of steroids pre-operatively. The overall postoperative complication rate was analysed as well as superficial and intra-abdominal sepsis occurrence. Mortality, re-operative and stoma rates were noted if reported and duration of follow-up was recorded. Any intestinal resection with anastomosis and/or strictureplasty was included in analysis.

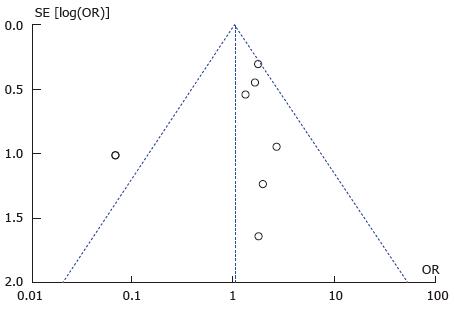

The Newcastle-Ottawa score for case-control studies was used to assess the quality of included studies. A maximum of 9 stars was attainable. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot for each outcome measure. Analysis was repeated without outlier high risk studies as required to reduce bias.

Extracted data were entered onto a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (MS Office 2010, Microsoft, WA, United States) by the lead author (HP) with verification from the co-author (PW). All statistical analyses were performed on Rev Man 5.3 (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman; 2014) and SPSS (version 20; IBM). The groups were compared for pre-operative characteristics using χ2 test without Yates correction and unpaired t test for dichotomous and continuous variables respectively. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Outcome measures for meta-analysis were chosen to test the null hypothesis of equivalent post-operative complications in both groups. Primary outcome measures comprised of total infectious complications, abdominal sepsis and anastomotic leak. Secondary outcome measures were wound sepsis, re-operation and mortality rate.

Dichotomous variables were analysed with the Mantel-Haenszel statistical method and random effects model. This particular model was chosen as it does not assume homogeneity between studies in terms of methodology or clinical characteristics and thus allows a more conservative analysis than the fixed effects model. Certain outcome measures were not reported by all studies and hence, the total number of patients in treatment and control groups was variable. No outcome measures were expressed as continuous variables.

Odds ratio, 95%CI, Forest and funnel plots were generated by Rev Man software. Study heterogeneity was assessed by Tau2 and χ2 testing with a quantitative measure of heterogeneity provided by the I2 measure. An I2 value of greater than 50% was considered evidence of substantial heterogeneity.

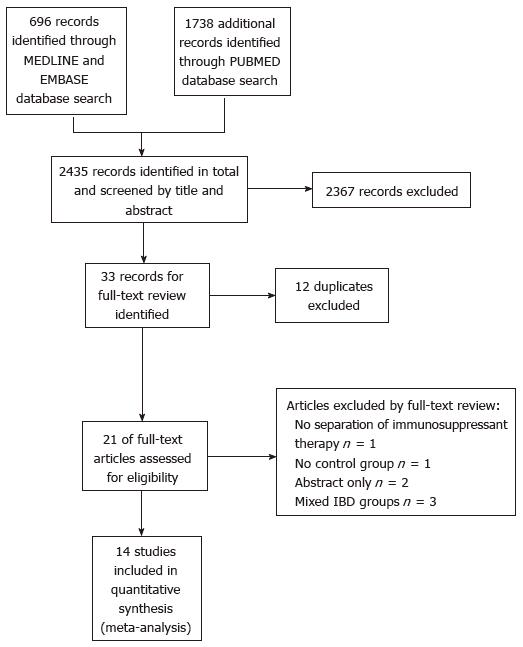

The search strategy identified a total of 2434 articles from Medline, Embase and Pubmed databases after application of English language and Human filters. Title and abstract screen eliminated 2367 articles with 33 remaining for analysis. Duplicates were removed at this stage as results from the 3 databases were amalgamated at this point. This left 21 articles for full text review. A total of 14 studies were relevant for meta-analysis after perusal of all 21 articles by both authors. (Figure 1; PRISMA reporting diagram)[7-11,15-23].

The characteristics of the 14 included studies are summarised in Table 1. There was no overlap of study population between included studies. All studies were retrospective case control type including two that reported formal case control matching[15,18]. A total of 5425 patients with CD were included in the analysis of which 1024 received anti-TNFα agents (treatment group) and 4401 received non-biological therapy (control group). All treatment cases had received anti-TNF agents within the preceding 12 wk before surgery. Infliximab was the only biologic agent used in 8/14 studies (57%). Patients in the remaining 6 studies received either Infliximab, Adalimumab or another biological agent. Mono or combination therapy with corticosteroids and/or immunomodulators (thiopurines) was used in the majority of the control group. Unsurprisingly, there was a significant difference between steroid use in the treatment and control groups (P = 0.0012, χ2 test). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of age (P = 0.135, unpaired t test) and gender distribution (P = 0.456, χ2 test). A subset of patients was eligible for assessment of difference in age as some studies reported age as mean and others as median. Thus, the mean was used and 3 studies could be analysed with no significant difference identified (n = 629 in total, unpaired t test P = 0.135). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of pre-operative abscess (P = 0.344, χ2 test) or stoma creation during the procedure (P = 0.66, χ2 test).

| Ref. | Country | Date | Type | n | NOS (0-9) | Pre-operative infliximab use (w) | Age1 | Sex (m) | Steroids | Abscess |

| Appau et al[7] | United States | 1998-2007 | Retrospective cohort | 389 | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | 35.8 (11.9) | 48.3% | 65% | 38% | ||||||

| No infliximab | 36.8 (14.4) | 45.9% | 77% | 44% | ||||||

| Canedo et al[10] | United States | 2000-2008 | Retrospective cohort | 225 | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | 26 (24.9-43.6) | 44% | NS | 37% | ||||||

| No infliximab | 32 (29.4-41.9) | 51% | NS | 30% | ||||||

| Colombel et al[11] | United States | 1998-2001 | Retrospective cohort | 270 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Infliximab | NS | NS | 36% | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | NS | NS | 42% | NS | ||||||

| El Hussuna et al[17] | Denmark | 2000-2007 | Retrospective cohort | 369 | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | 33 (18-62) | NS | NS | 34% | ||||||

| No infliximab | 37 (8-90) | NS | NS | 19% | ||||||

| Kasparek et al[15] | Munich | 2001-2008 | Case control match | 96 | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | 35 (17-66) | 43% | 94% | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | 39 (17-68) | 50% | 94% | NS | ||||||

| Kotze et al[23] | Brazil | 2007-2010 | Retrospective cohort | 76 | 7 | 4 | ||||

| Infliximab | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Marchal et al[18] | Netherlands | 1998-2002 | Case control match | 68 | 8 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | 36 (16-73) | NS | 35% | 50% | ||||||

| No infliximab | 38.7 (17-63) | NS | 35% | 41% | ||||||

| Mascarenhas et al[16] | United States | 2003-2010 | Retrospective cohort | 93 | 6 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | 35.6 (14.1) | 42% | 68% | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | 37 (14.1) | 60% | 44% | NS | ||||||

| Myrelid et al[21] | Europe | 1989-2002 | Retrospective cohort | 298 | 6 | 8 | ||||

| Infliximab | NS | 46% | NS | 20% | ||||||

| No infliximab | NS | 36% | NS | 20% | ||||||

| Nasir et al[20] | United States | 2005-2008 | Retrospective cohort | 370 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Infliximab | 38.2 (17-66) | 43% | 31% | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | 43.3 (17-77) | 41% | 45% | NS | ||||||

| Nørgård et al[9] | Denmark | 2000-2010 | Retrospective cohort | 2293 | 6 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | NS | 45% | 9% | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | NS | 41% | 14% | NS | ||||||

| Syed et al[8] | United States | 2004-2011 | Retrospective cohort | 325 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Infliximab | 38.2 (13.9) | 34% | 40% | 8% | ||||||

| No infliximab | 40 (14.3) | 45% | 35% | 9% | ||||||

| Tay et al[19] | United States | 1998-2002 | Retrospective cohort | 100 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Infliximab | NS | NS | 0% | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | NS | NS | 18% | NS | ||||||

| Uchino et al[22] | Japan | 2008-2011 | Retrospective cohort | 405 | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Infliximab | 36 (14-72) | 73% | 37% | NS | ||||||

| No infliximab | 37 (16-78) | 69% | 34% | NS | ||||||

| Total | 5377 |

Primary and secondary outcome measures from each study are summarised in Table 2.

| Ref. | Follow-up (d) | Anastomotic leak (%) | Abdominal sepsis (%) | Wound sepsis (%) | Total infectious complications (%) | Re-operation(%) | Mortality(%) |

| Appau et al[7] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 40 | 8 | 1.6 |

| No infliximab | 4.2 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 21.5 | 3 | 0 | |

| Canedo et al[10] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 13.8 | 21.5 | 3 | NS |

| No infliximab | 4.9 | 5 | 8.8 | 18.8 | 6 | NS | |

| Colombel et al[11] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | NS | NS | NS | 17.3 | NS | 0 |

| No infliximab | NS | NS | NS | 37 | NS | 0 | |

| El Hussuna et al[17] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 9.4 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 1.35 |

| No infliximab | 12.7 | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| Kasparek et al[15] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 8.3 | 6.2 | 18.8 | 56.2 | 23 | 2.1 |

| No infliximab | 12.5 | 10.4 | 14.6 | 41.6 | 21 | 0 | |

| Kotze et al[23] | 30 | ||||||

| Infliximab | NS | 10.5 | NS | NS | NS | 0 | |

| No infliximab | NS | 15.8 | NS | NS | NS | 3 | |

| Marchal et al[18] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 90 | 0 | 12.5 | 5 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| No infliximab | 5.8 | 10.3 | 2.5 | 12.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mascarenhas et al[16] | |||||||

| Inflixmab | 30 | 10.5 | NS | 10.5 | NS | NS | 0 |

| No infliximab | 4.1 | NS | 4.1 | NS | NS | 0 | |

| Myrelid et al[21] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 7.2 | NS | NS | 23.4 | 8 | NS |

| No infliximab | 8 | NS | NS | 22 | 7 | NS | |

| Nasir et al[20] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 3.4 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0 |

| No infliximab | 2 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.79 | |

| Nørgård et al[9] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 3.7 | NS | NS | NS | 7 | 0.46 |

| No infliximab | 2.7 | NS | NS | NS | 8 | 2.59 | |

| Syed et al[8] | |||||||

| Infliximab | NS | 3.3 | 18.7 | 18.7 | 36 | 16 | 1.3 |

| No infliximab | 3.4 | 15.4 | 11.4 | 25 | 13 | 0.57 | |

| Tay et al[19] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | 4.5 | 9.1 | NS | 13.6 | NS | NS |

| No infliximab | 5.1 | 5.1 | NS | 10.2 | NS | NS | |

| Uchino et al[22] | |||||||

| Infliximab | 30 | NS | 5.1 | 1.3 | NS | NS | NS |

| No infliximab | NS | 5.2 | 15.33 | NS | NS | NS |

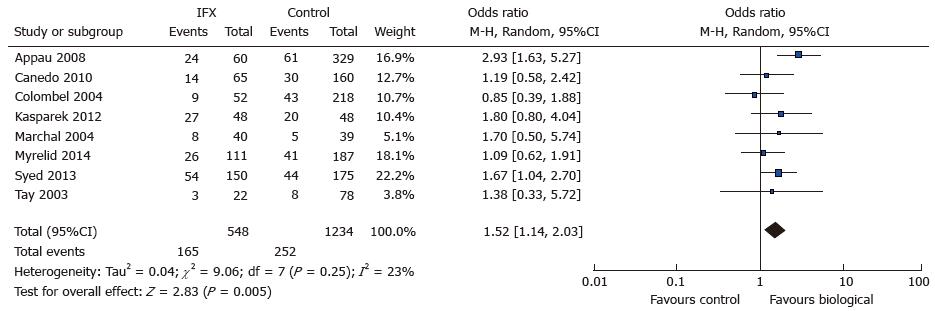

8 out of 14 studies[7-11,15,18-21] reported total infectious complications and entered 567 treatment cases and 1291 controls for analysis. Total infectious complications were reported in 4 out of 8 and were derived in 4 studies[7,10,18,21] by summation of reported site-specific complications. A total of 165 complications were reported in the treatment group as compared to 252 in the control group. There was an increased risk of total infectious complications in the treatment group (OR = 1.52; 95%CI: 1.14-2.03) that reached statistical significance (Z = 2.87; P = 0.005) (see Figure 2. Total infectious complications: Study event rate Forest plot). There was a low risk of heterogeneity amongst analysed studies as indicated by the I2 index (23%) and Tau2 variable (0.04; Rev Man 5.3). The Cochran Q test revealed some heterogeneity but not to a significant extent (χ2 = 9.06, df = 7; P = 0.25).

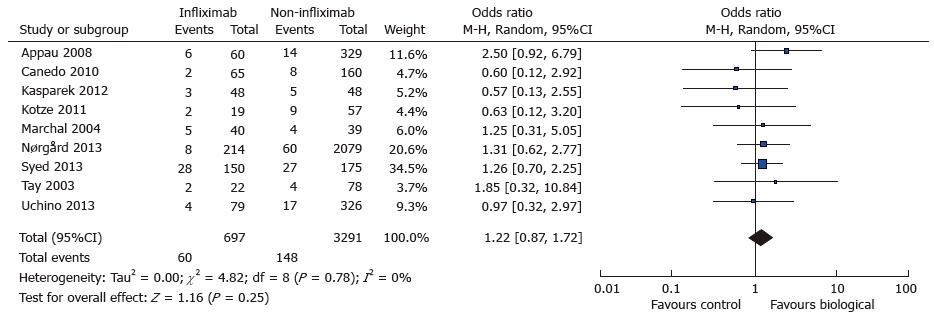

Abdominal sepsis was reported in nine out of fourteen studies[7-9,10,15,18,19,22,23] and comprised all abdominal septic complications including anastomtoic leak, abscess and/or fistula. Septic outcomes were reported in 7 studies and derived in two studies[9,15]. A total of 60 complications (60/697) were reported in the treatment group and 148 (148/3291) in the control. There was a trend towards increased postoperative abdominal sepsis in the treatment group (OR = 1.22; 95%CI: 0.87-1.72; P = 0.25). (see Figure 3. Postoperative abdominal sepsis: study event rates and forest plot) Heterogeneity amongst studies was minimal with I2 index of 0% and Tau2 variable of zero again. Cochran Q test supported lack of heterogeneity with a P value of 0.78.

A total of eleven studies reported on anastomotic leak rates in the two study groups which enabled 812 cases and 3356 controls to be entered for analysis[7-10,15-21]. There were 43 and 166 anastomotic complications reported in the case and control group respectively. There was a trend towards increased rate of anastomotic leak in the case/treatment group (OR = 1.19; 95%CI: 0.82-1.71; P = 0.26) (see Figure 4. Anastomotic leak: Study event rates and forest plot). Minimal heterogeneity was noted in the group (I2 = 0%; Tau2 = 0) as further confirmed by a low Cochran Q score (Q = 6.16; P = 0.72).

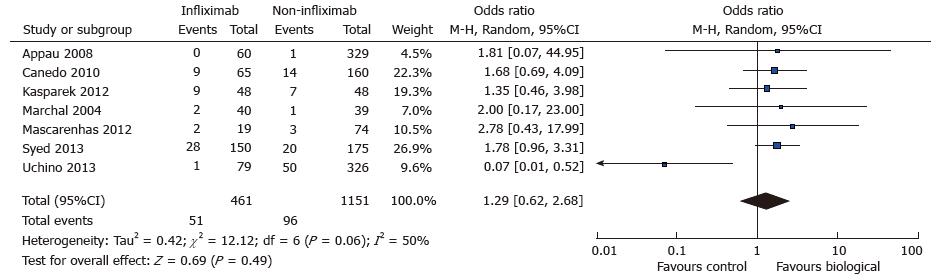

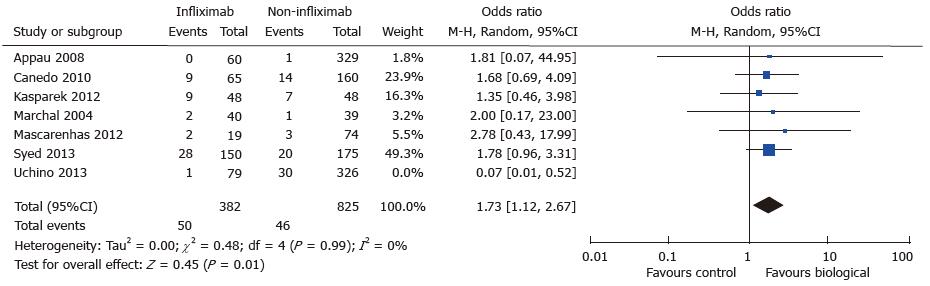

A total of seven studies reported data on postoperative wound infection in 461 cases and 1151 controls[7,8,10,15,16,18,22]. There were 51 and 96 wound complications reported in the case and control group respectively. There was a trend towards increased rate of wound sepsis in the treatment group (OR = 1.29; 95%CI: 0.62-2.68; P = 0.49) (see Figure 5. Wound infection: study event rates and forest plot). Substantial heterogeneity existed in the analysed studies with an I2 value of 50% and Tau2 value of 0.42. The Cochran Q test also revealed significant heterogeneity (P = 0.06). An outlier study[22] was identified on the funnel plot and exclusion from meta-analysis revealed an increased risk of postoperative wound infection in the treatment group (OR = 1.73; 95%CI: 1.12-2.67; P = 0.01) (see Figure 6. Wound infection: Funnel plot with outlier and Figure 7. Wound infection: Modified study event rates and forest plot). Heterogeneity also became minimal with the second analysis (Tau2 = 0; I2 = 0%).

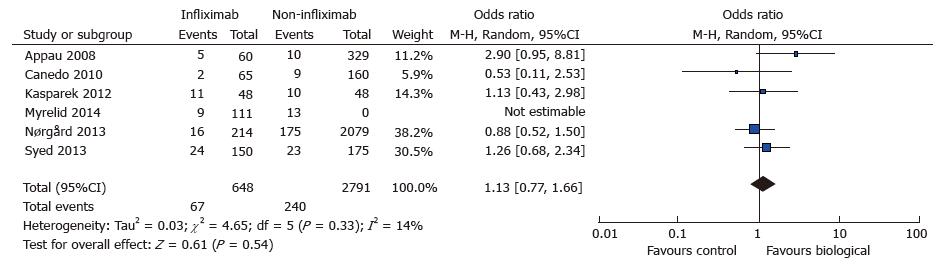

The rate of re-operation was not reported widely and only six studies were eligible for analysis[7-10,15,21]. Thus, a total of 648 cases and 2978 controls were analysed with a predictable low re-operation rate (67 vs 240). There was a potential trend for increased re-operation in the treatment group (OR = 1.12; 95%CI: 0.81-1.54; P = 0.54) with a minimal element of heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.00; I2 = 0%; Cochran Q = 4.65) (see Figure 8. Re-operation: Study event rates and forest plot).

Thirty-day mortality rates were reported in ten out of 14 studies and were low as expected from sample size (ranging from 0 to 3 actual events per study). There was only one large-scale study and thus further statistical analysis was not attempted[9].

Surgery for abdominal CD presents unique challenges to the surgeon and gastroenterologist. There are substantial risk factors pertaining to patient physiology, operative anatomy and co-existing medication. Anti-TNF agents have shown remarkable therapeutic efficacy in CD but concerns over increased rate of opportunistic infections and re-activation of latent TB remain[24,25]. Our meta-analysis demonstrates an increased risk of total infectious complications after abdominal surgery in patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy. Furthermore, after adjusting for publication bias a significant increase in wound sepsis was also identified. There was no increase in risk of intra-abdominal outcomes of anastomotic leak or abdominal sepsis for the same patient group. Re-operation rate was also not increased in the treatment group receiving anti-TNFα agents. Mortality rate was not compared between treatment and control groups as event numbers were too small for meaningful statistical analysis.

We defined total infectious complications to include abdominal, wound, urinary and respiratory sepsis and data was available in 8 out of 14 studies for analysis. Half of the included studies reported on the full spectrum of septic complications as described previously and data was derived in the remainder. There was some minor heterogeneity noted, which may be expected with such data given variability between studies in the criteria used to define infections arising from surgical wounds, or the urinary and respiratory tracts. Use of derivative data may also lead to a degree of inaccuracy as multiple septic complications could have occurred in the same patient and as a consequence result in over or underestimation of the true absolute event rate. Reassuringly, in spite of such confounders heterogeneity was slight with no major outliers seen on funnel plot.

The outcome measures of anastomotic leak, abdominal sepsis and wound infection were analysed separately in an attempt to define the relative contribution of each outcome to the increased risk for total infectious complications. A tendency was noted towards increased complications with biological therapy for anastomotic leak and abdominal sepsis though this was not significant for either measure. In addition, heterogeneity was minimal for both analyses. The more objective nature of abdominal sepsis and anastomotic leak in terms of diagnosis and data recording may explain homogeneity in the meta-analysis. Thus, the demonstrated increase in total infectious complications in the anti-TNFα group may be inferred to be “non-abdominal” in origin. A significant increase in wound infection rates were noted in patients treated with anti-TNFα agents.

Prior meta-analyses have revealed similar findings[12,14,26,27] apart from one analysis with equivalent outcomes across both groups[13]. An increased risk was found for major postoperative infection in 4 out of 5 meta-analyses that addressed this issue[12,14,26,27]. The meta-analysis that showed no difference between treatment and control groups divided postoperative complications into major and minor categories[13]. Postoperative sepsis was allocated to either category depending on type and thus it is difficult to extrapolate the true risk of sepsis in this analysis. Our meta-analysis differs from previous efforts in that we concentrated solely on infectious postoperative complications. Analyses were also conducted separately for site specific sepsis. This was performed to assess the excess burden of each outcome in patients on anti-TNFα therapy and has not been performed previously. It is also noted that heterogeneity was markedly reduced in our analysis as compared to previous efforts and could reflect more stringent inclusion criteria.

There are several limitations to our meta-analysis. Firstly, the severity of CD is likely to be disparate between the treatment and control groups. Anti-TNFα therapy is usually prescribed for disease that is refractory to steroids and/or immunomodulators. Thus, patients would be expected to possess a greater risk for postoperative complications as operative pathology may be more complex. We attempted to analyse this by comparing the presence of preoperative abscess or use of stoma as part of the operative procedure between the treatment and control groups. There was no significant difference identified in either of these parameters and that could indicate a degree of equivalence in disease severity between the treatment groups. However, it seems more likely that these parameters may not be sensitive enough to differentiate usefully between either group. A more objective comparison of CD severity between groups could be performed using quantitative measures such as the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (or Harvey-Bradshaw index). Unfortunately, no attempts at comparative disease severity stratification were performed within the included studies.

Patients in the control group received differing medications which again suggests that disease severity is not consistent across the control group. As previously mentioned postoperative complications are not defined or diagnosed in a standardised manner across the included studies. Thus, there may be over- or under- representation of the true extent of particular postoperative complications.

A significant limitation of this meta-analysis relates to the retrospective nature of all the included studies and the fact that only two studies attempted to match case and control groups albeit in a limited fashion[15,18]. This accurately reflects the existing literature and randomised controlled trials to address this issue are not feasible or ethical, so data is likely to be restricted to cohort studies in the future.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis may provide further support to the hypothesis of an increase in postoperative infectious complications in patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy. Our results are similar to other analyses on this subject and we have attempted to extract the specific infectious complications that are increased in this group of patients. A significant increase in both total infectious complications and wound infection rates in patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy were identified.

Our meta-analysis does not support the use of a protective stoma in patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy as a single risk factor, as there was no increase in abdominal sepsis, leak or re-operation rate. Our recommendation is to consider operative risk for patients with CD on an individual basis, incorporating recognised risk factors such as steroid use, hypoalbuminaemia, presence of fistula or abscess, in addition to preoperative anti-TNFα therapy alone. Furthermore, it seems sensible to attempt to mitigate risk of postoperative infection by planning surgery after cessation of anti-TNFα therapy where possible.

Current data reveals a contradictory picture of the adverse effects of pre-operative use of anti-TNFα agents and postoperative complications following bowel resection. It would be valuable to perform a comprehensive meta-analysis to identify any associations. The authors’ analysis aims to study specific septic complications in the Crohn’s disease patient receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) therapy to investigate postoperative risk in greater detail.

Not applicable as this is a meta-analysis from synthesised data from previous original studies.

Their meta-analysis demonstrates an increased risk of total infectious complications after abdominal surgery in patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy. This is the first meta-analysis to show a site-specific increase in septic complications, in particular wound sepsis.

The authors recommend risk assessment on an individual basis for patients with Crohn’s disease taking into account use of anti-TNFα therapy in combination with other known risk factors for post-operative septic complications. Discontinuation of anti-TNFα should be considered 6-8 wk prior to planned surgery.

Anti-TNFα therapy: Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapies are mostly monoclonal antibodies to tumour necrosis factor, a chemokine which is implicated in the abnormal inflammatory response associated with active inflammatory bowel disease. CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis; Fistulating disease: Enterocutaneous or inflammatory mass with entero-entero fistulae and/or fistula-in-ano.

This is a well-written review about the role of the pre-operative use of anti-TNF-alpha therapy that may increase risk of post-operative infectious complications after surgery for CD and in particular wound related infections.

P- Reviewer: Lakatos PL, Song J S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2987] [Cited by in RCA: 3047] [Article Influence: 132.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Feagan BG, Panaccione R, Sandborn WJ, D’Haens GR, Schreiber S, Rutgeerts PJ, Loftus EV, Lomax KG, Yu AP, Wu EQ. Effects of adalimumab therapy on incidence of hospitalization and surgery in Crohn’s disease: results from the CHARM study. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1493-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | D’Haens GR, Panaccione R, Higgins PD, Vermeire S, Gassull M, Chowers Y, Hanauer SB, Herfarth H, Hommes DW, Kamm M. The London Position Statement of the World Congress of Gastroenterology on Biological Therapy for IBD with the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization: when to start, when to stop, which drug to choose, and how to predict response? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:199-212; quiz 213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Desreumaux P, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF. Crohn’s disease: beyond antagonists of tumour necrosis factor. Lancet. 2008;372:67-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Billioud V, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Loss of response and need for adalimumab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:674-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Buck van Overstraeten A, Wolthuis A, D’Hoore A. Surgery for Crohn’s disease in the era of biologicals: a reduced need or delayed verdict? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3828-3832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Appau KA, Fazio VW, Shen B, Church JM, Lashner B, Remzi F, Brzezinski A, Strong SA, Hammel J, Kiran RP. Use of infliximab within 3 months of ileocolonic resection is associated with adverse postoperative outcomes in Crohn’s patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1738-1744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Syed A, Cross RK, Flasar MH. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy is associated with infections after abdominal surgery in Crohn’s disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:583-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nørgård BM, Nielsen J, Qvist N, Gradel KO, de Muckadell OB, Kjeldsen J. Pre-operative use of anti-TNF-α agents and the risk of post-operative complications in patients with Crohn’s disease--a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:214-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Canedo J, Lee SH, Pinto R, Murad-Regadas S, Rosen L, Wexner SD. Surgical resection in Crohn’s disease: is immunosuppressive medication associated with higher postoperative infection rates? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1294-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Young-Fadok T, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Sandborn WJ. Early postoperative complications are not increased in patients with Crohn’s disease treated perioperatively with infliximab or immunosuppressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:878-883. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Kopylov U, Ben-Horin S, Zmora O, Eliakim R, Katz LH. Anti-tumor necrosis factor and postoperative complications in Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2404-2413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rosenfeld G, Qian H, Bressler B. The risks of post-operative complications following pre-operative infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:868-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ahmed Ali U, Martin ST, Rao AD, Kiran RP. Impact of preoperative immunosuppressive agents on postoperative outcomes in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:663-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kasparek MS, Bruckmeier A, Beigel F, Müller MH, Brand S, Mansmann U, Jauch KW, Ochsenkühn T, Kreis ME. Infliximab does not affect postoperative complication rates in Crohn’s patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1207-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mascarenhas C, Nunoo R, Asgeirsson T, Rivera R, Kim D, Hoedema R, Dujovny N, Luchtefeld M, Davis AT, Figg R. Outcomes of ileocolic resection and right hemicolectomies for Crohn’s patients in comparison with non-Crohn’s patients and the impact of perioperative immunosuppressive therapy with biologics and steroids on inpatient complications. Am J Surg. 2012;203:375-378; discussion 378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | El-Hussuna A, Andersen J, Bisgaard T, Jess P, Henriksen M, Oehlenschlager J, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Olaison G. Biologic treatment or immunomodulation is not associated with postoperative anastomotic complications in abdominal surgery for Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:662-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marchal L, D’Haens G, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Noman M, Ferrante M, Hiele M, Bueno De Mesquita M, D’Hoore A, Penninckx F. The risk of post-operative complications associated with infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease: a controlled cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tay GS, Binion DG, Eastwood D, Otterson MF. Multivariate analysis suggests improved perioperative outcome in Crohn’s disease patients receiving immunomodulator therapy after segmental resection and/or strictureplasty. Surgery. 2003;134:565-572; discussion 572-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nasir BS, Dozois EJ, Cima RR, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Sandborn WJ, Loftus EV, Larson DW. Perioperative anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy does not increase the rate of early postoperative complications in Crohn’s disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1859-1865; discussion 1865-1866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Myrelid P, Marti-Gallostra M, Ashraf S, Sunde ML, Tholin M, Oresland T, Lovegrove RE, Tøttrup A, Kjaer DW, George BD. Complications in surgery for Crohn’s disease after preoperative antitumour necrosis factor therapy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Matsuoka H, Bando T, Ichiki K, Nakajima K, Tomita N, Takesue Y. Risk factors for surgical site infection and association with infliximab administration during surgery for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1156-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kotze PG, Coy CS. The impact of preoperative anti-TNF in surgical and infectious complications of abdominal procedures for Crohn’s disease: controversy still persists. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Khanna R, Feagan BG. Safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: current understanding of the potential for serious adverse events. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14:987-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Andersen NN, Jess T. Risk of infections associated with biological treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16014-16019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Narula N, Charleton D, Marshall JK. Meta-analysis: peri-operative anti-TNFα treatment and post-operative complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:1057-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yang ZP, Hong L, Wu Q, Wu KC, Fan DM. Preoperative infliximab use and postoperative complications in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2014;12:224-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |