Published online Mar 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.246

Peer-review started: June 17, 2015

First decision: August 24, 2015

Revised: September 5, 2015

Accepted: December 13, 2015

Article in press: December 15, 2015

Published online: March 27, 2016

Processing time: 277 Days and 5.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate changes over time in, and effects of sealing technology on, milk test results following pancreatectomy.

METHODS: From April 2008 to October 2013, 66 pancreatic resections were performed at the Iwakuni Clinical Center. The milk test has been routinely conducted at the institute whenever possible during pancreatectomy. The milk test comprises the following procedure: A nasogastric tube is inserted until the third portion of the duodenum, followed by injection of 100 mL of milk through the tube. If a chyle leak is present, the patient tests positive in this milk test based on the observation of a white milky discharge. Positive milk test rates, leakage sites, and chylous ascites incidence were examined. LigaSure™ (LS; Covidien, Dublin, Ireland), a vessel-sealing device, is routinely used in pancreatectomy. Positive milk test rates before and after use of LS, as well as drain discharge volume at the 2nd and 3rd postoperative days, were compared retrospectively. Finally, positive milk test rates and chylous ascites incidence were compared with the results of a previous report.

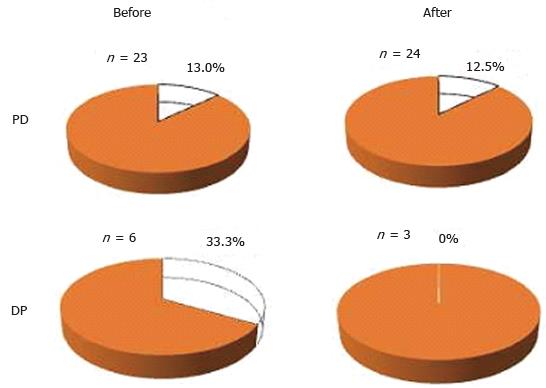

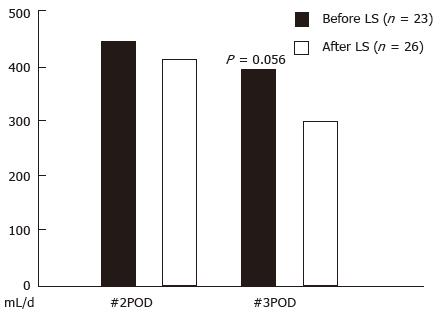

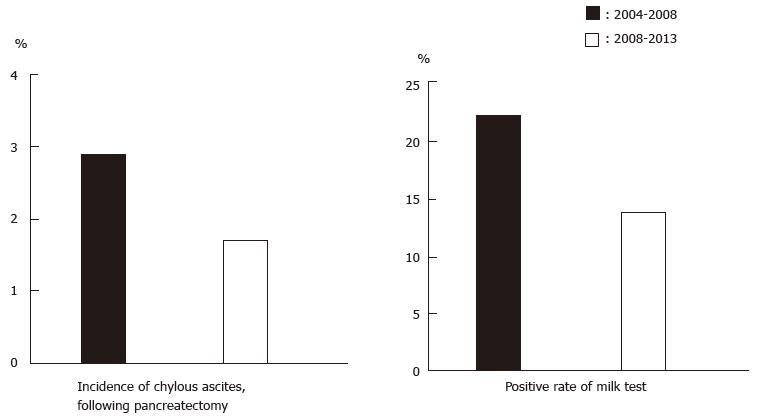

RESULTS: Fifty-nine milk tests were conducted during pancreatectomy. The positive milk test rate for all pancreatectomy cases was 13.6% (8 of 59 cases). One case developed postoperative chylous ascites (2.1% among the pancreatoduedenectomy cases and 1.7% among all pancreatectomies). Positive rates by procedure were 12.8% for pancreatoduodenectomy and 22.2% for distal pancreatectomy. Positive rates by disease were 17.9% for pancreatic and 5.9% for biliary diseases. When comparing results from before and after use of LS, positive milk test rates in pancreatoduodenectomy were 13.0% before and 12.5% after, while those in distal pancreatectomy were 33.3% and 0%. Drainage volume tended to decrease when LS was used on the 3rd postoperative day (volumes were 424 ± 303 mL before LS and 285 ± 185 mL after, P = 0.056). Both chylous ascites incidence and positive milk test rates decreased slightly compared with those rates from the previous study.

CONCLUSION: Positive milk test rates and chylous ascites incidence decreased over time. Sealing technology may thus play an important role in preventing postoperative chylous ascites.

Core tip: Chylous ascites is sometimes a severe complication of pancreatectomy. We previously reported that the milk test could serve to prevent chylous ascites following surgery. In this study, changes over time in milk test results, and effects of new energy devices on the test results, were investigated. Compared with the first report results, positive milk test rates and chylous ascites incidence were found to have decreased slightly. Use of the new energy devices also tended to result in decreased drainage volume. These findings suggest that the vessel-sealing technology could play an important role in preventing postoperative chylous ascites.

- Citation: Aoki H, Utsumi M, Sui K, Kanaya N, Kunitomo T, Takeuchi H, Takakura N, Shiozaki S, Matsukawa H. Changes over time in milk test results following pancreatectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(3): 246-251

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i3/246.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.246

Chylous ascites is a condition defined by the secretion of milky white fluid with high triglyceride content. Generally, it occurs due to traumatic injury or obstruction of the lymphatic system. Although it is a rare condition, there are multiple causes, such as neoplasm, inflammation, infection, surgery, trauma, and so on[1]. As for postoperative causes, pancreatic surgery is a major cause of chylous ascites[2-6]. According to reports, rates of chylous ascites incidence after pancreatoduodenectomy ranged from 1.8% to 13%. The cisterna chili lies anteriorally of the first and second lumbar vertebrae, on the same plane as the pancreas. Injury to the cisterna chili or its tributaries can occur during pancreatic resection. We experienced several cases of chylous ascites after pancreatectomy, and the condition is often associated with prolonged hospitalization. These are the reasons why we started studying the milk test in 2004 for its potential as a treatment to prevent the development of chylous ascites following pancreatic resection[5].

On the other hand, remarkable advances have been witnessed in surgical energy technology. Such surgical energy devices as the vessel-sealing system represent a new hemostatic technology based on the combination of pressure and bipolar electrical energy that leads to the denaturation of collagen and elastin in the vessel walls and fusion of these into a hemostatic seal. Besides hemostatic ability, the new surgical energy devices might be used to block lymphatic flow. In terms of technical issues, we cannot ignore the effects of such new surgical energy technologies.

The aim of this study is to investigate changes over time in milk test results following pancreatectomy and the effects of vessel-sealing devices on milk test results.

From April 2008 to October 2013, 66 pancreatic resections were performed at the Iwakuni Clinical Center, Iwakuni, Japan. Starting in 2004, the milk test has been routinely conducted whenever possible during pancreatectomy. Briefly, the milk test is conducted in the following way: A nasogastric tube is inserted until the third portion of the duodenum, followed by injection of 100 mL of milk through the tube. If a chyle leak is present, the patient tests positive in this milk test based on the observation of a white milky discharge (Figure 1). Seven cases were excluded: 2 laparoscopic surgeries, as well as 2 emergency and 3 unexpected pancreatic resections. The milk test was used in 59 of these 66 cases [47 pancreatoduodenectomy (PD); 2 total pancreatectomy (TP); 9 distal pancreatectomy (DP); 1 middle pancreatectomy]. Final diagnoses were 21 cases of pancreatic cancer, 12 intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, 9 bile duct cancer, 7 ampulla of Vater cancer, 2 each of chronic pancreatitis, gallbladder cancer, and duodenal cancer, and 1 each of metastatic pancreatic cancer and endocrine tumor.

Positive milk test rates, leakage sites, and chylous ascites incidence were examined. Since May 2011 in the Iwakuni Clinical Center, a vessel-sealing system (LigaSure small jaw instrument) is routinely used in pancreatectomy. Positive milk test rates before and after introduction of LigaSure (LS) as well as drain discharge volume were compared retrospectively. Finally, positive milk test rates and chylous ascites incidence were compared with the results of our previous report (conducted from 2004 to 2008)[5].

Variables were compared using χ2 test or Student’s t test. JMP 9 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) was used for all analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was reviewed and approved by the Iwakuni Clinical Center Institutional Review Board.

Positive milk test rate among all pancreatectomy cases was 13.6% (8 of 59 cases). Leakage sites were as follows: Superior mesenteric artery: 4 cases; superior mesenteric vein: 2; left renal vein: 1; paraaorta: 1; and mesentery: 1. One case had two leakage sites. Six of 8 cases presented with leakage sites around superior mesenteric vessels (Table 1). One case demonstrated postoperative chylous ascites. Incidence of chylous ascites was 2.1% among the PD cases and 1.7% among all pancreatectomies. This case was milk test positive and treated with a conservative method using octreotide.

Positive rates by procedure were 12.8% for PD and 22.2% for DP (Table 2). No significant differences in positive rates were observed between the different procedures. Positive rates by diseases were 17.9% in pancreatic diseases and 5.9% in biliary diseases. When limited to PD patients in pancreatic diseases, the positive rate reached 13.3%. The positive rates were higher in pancreatic diseases, but this difference did not reach the level of statistical significance (Table 3).

| Procedure | Positive | Negative |

| PD (n = 47) | 6 (12.8%) | 41 |

| DP (n = 9) | 2 (22.2%) | 7 |

| Disease | Positive | Negative |

| Biliary disease (n = 17) | 1 (5.9%) | 16 |

| Panceatic disease (n = 39) | 7 (17.9%) | 32 |

| Panceatic disease with PD (n = 30) | 4 (13.3%) | 26 |

When comparing figures before and after the introduction of LS, positive milk test rates for PD and TP were 13.0% before and 12.5% after, and for DP 33.3% and 0%. There was no statistical significance (Figure 2). As for drain discharge volume, the two groups were compared on the 2nd and 3rd postoperative days (POD) on average. Drain discharge volumes for the 2nd POD cases were 454 ± 237 mL (mean ± SD) before introduction of LS and 383 ± 279 mL after; for the 3rd POD cases, the volumes were 424 ± 303 mL and 285 ± 185 mL, respectively (Figure 3). Although no statistical differences were evident, a tendency for decreased drainage volume was observed when using LS on the 3rd POD cases (P = 0.056).

Incidences of chylous ascites were 2.9% in the previous study’s period (2004-2008) among all pancreatectomy[5] cases and 1.7% in this study. Positive milk test rates were 22.1% in the previous study[5] and 13.6% in this study (Figure 4). Both rates represented a slight decrease compared with the first report, but this difference did not reach the level of statistical significance.

Postoperative chylous ascites is a relatively rare condition, but once it occurs the disorder can cause hyponutrition and prolonged hospitalization.

Positive milk test rates by procedure were higher for DP than for PD, but this difference was not significant. In our previous report, the incidences were nearly the same. Some authors report lower rates of chylous ascites in DP[3], but others do not[6]. This result might be due to the difference in disease incidence itself, but this aspect is not yet fully understood. According to the positive milk test rates, chylous ascites might occur at least equally in DP. Positive milk test rates by disease were higher in pancreatic than in biliary disease. The existence of concomitant pancreatitis with pancreatic disease might have played a role in this result. In one study, van der Gaag et al[4] reported that chronic pancreatitis is one of the risk factors for the development of postoperative chylous ascites. Kuboki et al[6] reported manipulation of the paraaortic area, retroperitoneal invasion, and early enteral feeding to be independent risk factors associated with chylous ascites. The first two of these three factors may have had something to do with the operative procedure itself. As for early enteral feeding, Malik et al[2] also alerted the medical community about the risk for chyle leak in this treatment. Careful observation of drain discharge is thus necessary before allowing such patients to begin meal intake after pancreatectomy.

The management algorithm used to treat chylous ascites integrates repeat palliative paracentesis, dietary measures, total parenteral nutrition therapy, peritoneovenous shunting, and surgical closure of the lymphoperitoneal fistula. Somatostatin therapy should be attempted with or without total parenteral nutrition early in the course of treatment of chylous ascites before any invasive steps are taken[7]. In addition, Kawasaki et al[8] reported effectiveness of lymphangiography not only for diagnosis but also for treatment of postoperative chylothrax and chylous ascites. In our experience, albeit somewhat limited, none of the cases required surgical treatment for postoperative chylous ascites. Chylous ascites should thus be treated by surgical procedure at the time of the initial operation. We emphasized the importance of steady ligation in our previous report. But now, new surgical energy technologies are gradually replacing that technique.

New surgical energy devices-such as the harmonic scalpel or vessel-sealing system-are reported to be useful in reducing drain discharge in colonic surgery[9] and in axillary lymphadenectomy[10], respectively. Nakayama et al[11] reported the utility of an ultrasonic scalpel in sealing the thoracic duct based on use of a pig model. The burst pressure after sealing by this ultrasonic scalpel was 188-203 mmHg, which is far above the pressure at which lymph vessels are occluded.

The question is what type of surgical energy device should we use to prevent chylous ascites? Seehofer et al[12] performed a comparison among a new surgical tissue management system that combines ultrasonic vibration and tissue dissection with bipolar coagulation [thunderbeat (TB)], a conventional ultrasonic scissor [Harmonic Ace (HA)], and a bipolar vessel clamp (LS), in terms of safety and efficacy. The burst pressure of the TB technique in the larger-artery category (5-7 mm) was superior to that of the HA technology. The dissection speed of the TB was significantly faster than that of the LS. Although seal width was influenced by the width of the jaw, LS had the widest seal width and the fewest gas pockets. This means that histologically LS is superior in terms of seal reliability and prevention of thermal injury. Janssen[13] conducted a systematic search for randomized controlled trials that compared the effectiveness and costs of vessel-sealing devices with those of other electrothermal or ultrasonic devices in abdominal surgical procedures. The researchers involved in the study concluded that vessel-sealing devices may be considered safe and that their use may reduce costs due to reduced blood loss and shorter operating time in some abdominal surgical procedures compared to mono- or bipolar electrothermal devices. Though thermal injury is an issue that needs to be resolved, surgical energy devices can be used as another contributing factor for prevention of chylous ascites.

In our study, although there was no significant difference, both chylous ascites incidence and positive milk test rates decreased over time. The reasons for that are partly because we are more knowledgeable about chylous ascites and because of the technical advances made especially in surgical energy devices. Although we could not prove our results definitively, we think it is a matter of more numbers of cases. We therefore started planning in November 2013 a randomized prospective milk test study. In this study, we will investigate the utility of the milk test and chyle leak sites more comprehensively. We plan for the next study to include comparisons of different surgical energy devices.

In conclusion, positive milk test rates were higher in DP and pancreatic disease. Both chylous ascites incidence and positive milk test rates decreased over time. Based on the study results, surgical energy devices should be used as another contributing factor for the prevention of chylous ascites. Further investigation is needed to confirm the utility of the milk test.

Postoperative chylous ascites is a rare condition, but once it occurs the disorder can cause hyponutrition and prolonged hospitalization. Although chylous ascites after pancreatectomy has recently become an issue in the field of abdominal surgery, methods for prevention of chylous ascites are not well established. The authors therefore investigated the milk test as a method to resolve this condition starting in 2004. In their previous study, use of the milk test contributed to a decrease in incidence of chylous ascites. In this study, they looked at changes over time in milk test results. In addition, they assessed the effects of energy devices, which first appeared during the study period and now cannot be ignored in cases of abdominal surgery.

The authors believe that the milk test is a useful method for detecting lymphorrhea during surgery. But to truly prove its utility, a prospective study is necessary. The authors therefore initiated a prospective randomized study in 2013.

To date, many papers have been published about chylous ascites, but most of them are focused on its pathogenesis or treatment. There is no study about prevention, especially in the case of pancreatectomy. The authors emphasize that postoperative chylous ascites should and can be prevented during surgery. The results of this study also suggest that new energy devices may play an important role in decreasing drain discharge.

A benefit to the milk test is that milk is easy to obtain and inexpensive. When the milk test is used, there is no need for special drugs or instruments. In addition, no complications accompany use of the milk test.

Reviewers mentioned that our paper provided interesting methodology and results. They stated that they are looking forward to the new study results.

P- Reviewer: Venskutonis D S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Cárdenas A, Chopra S. Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1896-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Malik HZ, Crozier J, Murray L, Carter R. Chyle leakage and early enteral feeding following pancreatico-duodenectomy: management options. Dig Surg. 2007;24:418-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Assumpcao L, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, Edil B, Choti MA, Herman JM, Geschwind JF, Hong K, Georgiades C, Schulick RD. Incidence and management of chyle leaks following pancreatic resection: a high volume single-center institutional experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1915-1923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van der Gaag NA, Verhaar AC, Haverkort EB, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Chylous ascites after pancreaticoduodenectomy: introduction of a grading system. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:751-757. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Aoki H, Takakura N, Shiozaki S, Matsukawa H. Milk-based test as a preventive method for chylous ascites following pancreatic resection. Dig Surg. 2010;27:427-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kuboki S, Shimizu H, Yoshidome H, Ohtsuka M, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Miyazaki M. Chylous ascites after hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. Br J Surg. 2013;100:522-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Leibovitch I, Mor Y, Golomb J, Ramon J. The diagnosis and management of postoperative chylous ascites. J Urol. 2002;167:449-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kawasaki R, Sugimoto K, Fujii M, Miyamoto N, Okada T, Yamaguchi M, Sugimura K. Therapeutic effectiveness of diagnostic lymphangiography for refractory postoperative chylothorax and chylous ascites: correlation with radiologic findings and preceding medical treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:659-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sista F, Abruzzese V, Schietroma M, Cecilia EM, Mattei A, Amicucci G. New harmonic scalpel versus conventional hemostasis in right colon surgery: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Dig Surg. 2013;30:355-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nespoli L, Antolini L, Stucchi C, Nespoli A, Valsecchi MG, Gianotti L. Axillary lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. A randomized controlled trial comparing a bipolar vessel sealing system to the conventional technique. Breast. 2012;21:739-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nakayama H, Ito H, Kato Y, Tsuboi M. Ultrasonic scalpel for sealing of the thoracic duct: evaluation of effectiveness in an animal model. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9:399-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Seehofer D, Mogl M, Boas-Knoop S, Unger J, Schirmeier A, Chopra S, Eurich D. Safety and efficacy of new integrated bipolar and ultrasonic scissors compared to conventional laparoscopic 5-mm sealing and cutting instruments. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2541-2549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Janssen PF, Brölmann HA, Huirne JA. Effectiveness of electrothermal bipolar vessel-sealing devices versus other electrothermal and ultrasonic devices for abdominal surgical hemostasis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2892-2901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |