Published online Mar 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.222

Peer-review started: July 8, 2015

First decision: September 8, 2015

Revised: December 26, 2015

Accepted: January 5, 2016

Article in press: January 7, 2016

Published online: March 27, 2016

Processing time: 258 Days and 19.3 Hours

Intra-abdominal adhesions following abdominal surgery represent a major unsolved problem. They are the first cause of small bowel obstruction. Diagnosis is based on clinical evaluation, water-soluble contrast follow-through and computed tomography scan. For patients presenting no signs of strangulation, peritonitis or severe intestinal impairment there is good evidence to support non-operative management. Open surgery is the preferred method for the surgical treatment of adhesive small bowel obstruction, in case of suspected strangulation or after failed conservative management, but laparoscopy is gaining widespread acceptance especially in selected group of patients. "Good" surgical technique and anti-adhesive barriers are the main current concepts of adhesion prevention. We discuss current knowledge in modern diagnosis and evolving strategies for management and prevention that are leading to stratified care for patients.

Core tip: Adhesive disease is a consequence of all intra-peritoneal surgeries. We decided to carry out a systematic review about the adhesive small bowel obstruction because it is still difficult to make differential diagnosis and to understand the right time to operate and which surgical technique to perform. Besides there is a way to prevent major adhesive disease: "Good" surgical technique and anti-adhesive barriers are the main current concepts of adhesion prevention. We discuss all current knowledge in this field.

- Citation: Catena F, Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Ansaloni L, De Simone B, Sartelli M, Van Goor H. Adhesive small bowel adhesions obstruction: Evolutions in diagnosis, management and prevention. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(3): 222-231

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i3/222.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.222

Adhesive disease is the most frequently encountered disorder of the small intestine; in one review of 87 studies including 110076 patients, the incidence of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO) following all types of abdominal operations was 2.4%[1].

In North America, there are more than 300000 annual hospital admissions for ASBO accounting for 850000 d of inpatient care, costing more than $1.3 billion in medical expenditures and contributing to more than 2000 deaths annually[2].

Dembrowski published the first data on induction of adhesions in an animal model in 1889 and in the following 120 years there have been extensive studies both in vitro and in vivo[3].

In the past decade, limited clinical research has produced uncertainty about best practice with subsequent international variation in delivery and in outcome.

There is a diagnostic dilemma on how to distinguish between adhesive SBO and other causes, and how to distinguish between ASBO that needs emergency surgery and ASBO that can be successfully treated conservatively.

ASBO after peritoneal cavity surgery is a well-known disease entity that still harbors challenges regarding prevention, diagnosis and treatment despite general improvements in care. Good surgical technique, e.g., laparoscopy, and anti-adhesive barriers at initial surgery seem to reduce ASBO but reports have conflicting results and only provide general conclusions which do not apply for each individual patient. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) has improved diagnosis of ASBO in general but cannot be performed in each patient (severe vomiting, kidney failure) and fails to accurately identify adhesions as the cause. Also, predicting which treatment should be installed and success of treatment by CT is under debate. Regarding surgical treatment laparoscopy has gained popularity but also is associated with increased risk of iatrogenic complications. Particularly, identifying patients who might benefit from laparoscopic adhesiolysis and who should not and should be treated by open surgery is a challenge.

Therefore, ASBO diagnosis, treatment and prevention are important for reducing mortality, morbidity and for socioeconomic reasons.

The aim of this review is to provide an update of the current controversies over diagnosis, non-operative/operative management and prevention of ASBO.

We searched the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, limited to the final search date (31/03/2015) and not limited to English language publications.

We used the search terms “small bowel” or “obstruction” in combination with the terms “adhesions” or “adhesive” or “adherences”.

We largely selected publications in the past five years, but did not exclude commonly referenced and highly regarded older publications.

We also searched the reference lists of articles identified by this search strategy and selected those we judged relevant.

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov (01/01/2000-31/03/2015) for current trials in ASBO.

Intra-abdominal adhesions following abdominal surgery represent a major unsolved problem; in patients with abdominal pain, ASBO is a common cause that accounts for 4% of all emergency department admissions and 20% of emergency surgical procedures[4].

These fibrous bands are thought to occur in up to 93% of patients undergoing abdominal surgery and can complicate future surgery considerably[5].

Adhesion formation can result in significant morbidity, mortality and infertility in women, and adhesion-related complications are also responsible for up to 74% cases of ASBO in adults and 30% of re-admissions at 4 years after an incident intra-abdominal surgery[6].

It is unknown whether the increase in laparoscopic intra-abdominal surgery has translated into fewer postoperative complications due to adhesions; a recent review of 11 experimental studies involving seven animal models and four human studies reported mixed results. Some reported decreased rates of adhesion formation after laparoscopy. However, there was significant heterogeneity among the human studies[7,8].

Furthermore, some evidence suggests that this decrease in adhesion formation has not necessarily translated to a decrease in adhesion-related obstruction; in a recent randomized, multi-center trial comparing outcomes in laparoscopic vs conventional approaches in colorectal surgery for malignancy, there was no difference between the two groups in obstruction-related complications at 3-year follow-up consultations[9].

However, in a long-term follow-up study examining the rate of hospitalization due to ASBO for patients operated on due to suspected appendicitis, the laparoscopic approach resulted in significantly lower rates compared to open surgery. However, frequency of ASBO after the index surgery was low in both groups[10].

In a recent meta-analysis the incidence of adhesive small bowel obstruction was highest in pediatric surgery (4.2%, 2.8% to 5.5%; I2 = 86%) and in lower gastrointestinal tract surgery (3.2%, 2.6% to 3.8%; I2 = 84%); the incidence was lowest after abdominal wall surgery (0.5%, 0.0% to 0.9%; I2 = 0%), upper gastrointestinal tract surgery (1.2%, 0.8% to 1.6%; I2 = 80%), and urological surgery (1.5%, 0.1% to 3.0%; I2 = 67%)[1].

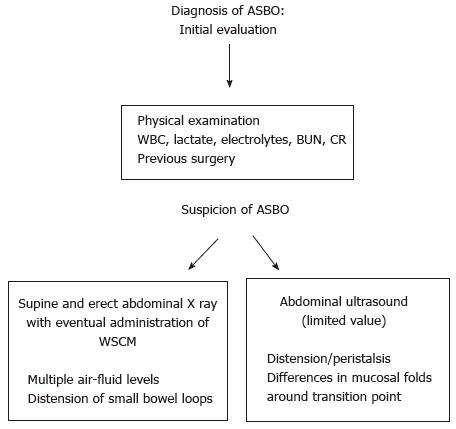

The first step in the diagnostic work flow for ASBO is a detailed anamnesis and physical examination, followed by the evaluation of a complete blood count with differential especially white blood cell (WBC) count, electrolytes including blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, C-reactive protein, serum lactate, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase (CK). In patients who present with systemic signs (e.g., fever, tachycardia, hypotension, altered mental status), additional laboratory investigation should include arterial blood gas and serum lactate. Although patients with ASBO generally may complain a varied assortment of symptoms, such as discontinuous abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, associated, in the vast majority of cases, with a history of previous abdominal surgery[11], these clinical symptoms contribute only to some extent to the diagnosis of ASBO[12]. Unfortunately, the clinical symptoms of ASBO are even less consistent predictors in differentiating patients with bowel strangulation who need emergency surgical intervention[13]. Laboratory tests may be more useful to estimate the grade of systemic illness, than to confirm clinical suspicions. Actually the typical inflammatory markers, like WBC count and CPR levels, cannot discriminate between the inflammation due to ASBO and that caused by other inflammatory conditions[14,15]. In the case of bowel ischemia due to strangulation, these markers cannot discriminate the patients who benefit from conservative treatment and those who need surgery[16,17]. Nevertheless, when evolution to ischemia follows, serum lactate, LDH and CK may increase due to bowel hypoperfusion[16]. However, since LDH and CK increase in any ischemic state, they are consequently quite unspecific. Instead, because serum lactate rises only at a stage when widespread bowel infarction is already well established, lactate increase is highly sensitive, but not specific, for ischemia in patients with ASBO (sensitivity 90%-100%, specificity 42%-87%), being thus a robust sign to proceed to urgent surgery[18,19]. Recent reports indicate that, although there is no reliable clinical or laboratory marker for intestinal ischemia, an intestinal fatty acid binding protein, which is released by necrotic enterocytes, may become a useful marker for the detection of bowel ischemia[20]. In conclusion, laboratory tests can simply indicate general disease severity and can be used to support or rule out an emergency surgical choice only in the context of agreement of a number of other clinical findings. Moreover, serum tests are clearly worthwhile in the evaluation of any patient with acute obstruction, because they may indicate needed adjustment of electrolyte abnormalities and fluid resuscitation (Figure 1).

While ASBO may be suspected based only upon risk factors, symptoms, and physical examination, abdominal imaging is usually required to confirm the diagnosis, eventually detecting the location of obstruction and identifying complications, like ischemia, necrosis, and perforation[21,22]. Although multiple imaging modalities are available to confirm a suspected diagnosis of ASBO, plain radiography and abdominal CT are those most suitable and useful. Thus, the preliminary assessment for all patients suspected for ASBO should include supine and erect plain abdominal radiography that can display multiple air-fluid levels with distension of small bowel together with the absence of gas in the colon[23]. However, it must be said that the reason or site of obstruction is usually not clear on plain radiography, since a specific site between the enlarged proximal and undilated distal bowel frequently cannot be recognized with certainty. For the diagnosis of ASBO, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of plain X-ray are from 79% to 83%, from 67% to 83%, and from 64% to 82%, respectively (Figure 2).

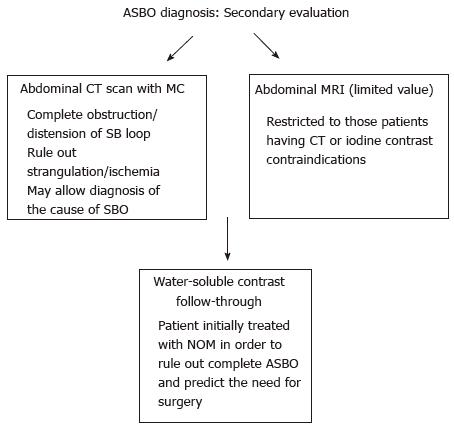

Abdominal CT scans (Figure 3), especially with administration of oral or intravenous contrast medium, perform better than plain X-ray in finding the transition point, evaluating the severity of obstruction, identifying the cause of obstruction, and recognizing complications (ischemia, necrosis, and perforation)[24]. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of CT scans for ASBO diagnosis are, respectively, from 90% to 94%, 96%, and 95%[25]. CT has been demonstrated to be highly diagnostic in ASBO, especially in all patients with inconclusive plain X-ray[26]. However, it should not be routinely implemented in the diagnosis-making process except when clinical history, physical examination, and plain film were not convincing for ASBO diagnosis[27], since these are readily available, less expensive, expose the patient to less radiation, and may highlight the need for abdominal CT in some patients.

Abdominal ultrasound and magnetic resonance enterography may be useful for the diagnosis of ASBO only in selected patients and their use should be restricted to those patients having CT or iodine contrast contraindications[28].

Although small bowel contrast studies, in general, have a limited role in the initial diagnosis of ASBO and in some circumstances, like in the presence of perforation, some of them, as those with the use of barium, are contraindicated[24], instead those using water-soluble contrast agents (WSCA), being safer than barium in cases of perforation and peritoneal spread, are extremely valuable in patients undergoing initial non-operative conservative management in order to rule out complete ASBO and predict the need for surgery[29]. In this sense, small bowel WSCA studies in the presence of ASBO have not only diagnostic, but especially therapeutic value[26].

For patients presenting with ASBO without signs of strangulation, peritonitis or severe intestinal impairment there is good evidence to support NOM.

Free intraperitoneal fluid, mesenteric edema, lack of the “small bowel feces sign” at CT-scan, history of vomiting, severe abdominal pain (VAS > 4), abdominal guarding, raised white cell count and devascularized bowel at CT-scan predict the need for emergent laparotomy[30].

Moreover, patients with repeated ASBO episodes, many prior laparotomies for adhesions and prolonged conservative treatment should be cautiously selected to find out only those who may benefit from early surgical interventions[30].

At present, there is no consensus about when conservative treatment should be considered unsuccessful and the patient should undergo surgery; in fact, the use of surgery to solve ASBO is controversial, as surgery induces the formation of new adhesions[30].

Level I data have shown that NOM can be successful in up to 90% of patients without peritonitis[31].

As a counterpart, a delay in operation for ASBO places patients at higher risk for bowel resection. A retrospective analysis showed that in patients with a ≤ 24 h wait time until surgery, only 12% experienced bowel resection and in patients with a ≥ 24 h wait time until surgery, 29% required bowel resection[32].

Schraufnagel et al[33] showed that in their huge patient cohort, the rates of complications, resection, prolonged length of stay and death were higher in patients admitted for ASBO and operated on after a time period of ≥ 4 d.

The World Society of Emergency Surgery 2013 guidelines stated that NOM in the absence of signs of strangulation or peritonitis can be prolonged up to 72 h. After 72 h of NOM without resolution, surgery is recommended[30].

There are no objective criteria that identify those patients who are likely to respond to conservative treatment. Less clear, in fact, is the way to predict between progression to strangulation or resolution of ASBO. Some authors suggested the following as strong predictors of NOM failure: The presence of ascites, complete ASBO (no evidence of air within the large bowel), increased serum creatine phosphokinase and ≥ 500 mL from nasogastric tube on the third NOM day[30].

However, at any time, if there is an onset of signs of strangulation, peritonitis or severe intestinal impairment, NOM should be discontinued and surgery is recommended.

It is really difficult to predict the risk of operation among those patients with ASBO who initially underwent NOM[30].

Randomized clinical trials showed that there are no differences between the use of nasogastric tubes compared to the use of long tube decompression[34].

In any case, early tube decompression is beneficial in the initial management, in addition to required attempts of fluid resuscitation and electrolyte imbalance correction. For challenging cases of ASBO, the long tube should be placed as soon as possible, more advisable by endoscopy, rather than by fluoroscopic guide[35].

Several studies investigated the diagnostic-therapeutical role of WSCA[36]. Gastrografin is the most commonly utilised contrast medium. It is a mixture of sodium diatrizoate and megluminediatrizoate. Its osmolarity is 2150 mOsm/L. It activates movement of water into the small bowel lumen. Gastrografin also decreases oedema of the small bowel wall and it may also enhance smooth muscle contractile activity that can generate effective peristalsis and overcome the obstruction[37].

The administration of WSCA proved to be effective in several randomized studies and meta-analysis. Three recent meta-analyses showed no advantages in waiting longer than 8 h after the administration of WSCA[26] and demonstrated that the presence of contrast in the colon within 4-24 h is predictive of ASBO resolution. Moreover, for patients undergoing NOM, WSCA decreased the need for surgery and reduced the length of hospital stay[38,39].

Oral therapy with magnesium oxide, L. acidophilus and simethicone may be considered to help the resolution of NOM in partial ASBO with positive results in shortening the hospital stay[40].

Lastly hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be an option in the management of high anesthesiologic risk patients for whom surgery should be avoided[41].

No agreement exists about the possibility to predict the recurrence risk. Factors associated with a higher risk of recurrence are age < 40 years, matted adhesion and postoperative surgical complications[42]. Compared to traditionally conservatively treated patients, Gastrografin use does not affect either the ASBO recurrence rates or recurrences needing surgery (Figure 4)[29].

Until recently open surgery has been the preferred method for the surgical treatment of ASBO (in case of suspected strangulation or after failed conservative management), and laparoscopy has been suggested only in highly selected group of patients (preferably in case of first episode of ASBO/or anticipated single band adhesion) using an open access technique and the left upper quadrant for entry[30] (Figure 5).

More recently, the use of laparoscopy is gaining widespread acceptance and is becoming the preferred choice in centers with specific expertise.

A meta-analysis by Li et al[43] found that there was no statistically significant difference between open vs laparoscopic adhesiolysis in the number of intraoperative bowel injuries, wound infections, or overall mortality. Conversely there was a statistically significant difference in the incidence of overall and pulmonary complications and a considerable reduction of prolonged ileus in the laparoscopic group compared with the open group. The authors concluded that laparoscopic approach is safer than the open procedure, but only in the hands of experienced laparoscopic surgeons and in selected patients[43].

However, no randomized controlled trial comparing open to laparoscopic adhesiolysis exists to date, and both the precise indications and specific outcomes of laparoscopic adhesiolysis for adhesive SBO remain poorly understood. The only randomized controlled trial aiming to provide level Ib evidence to assess the use of laparoscopy in the treatment of adhesive small bowel obstruction is currently ongoing, having the length of postoperative hospital stay as the primary endpoint and the passage of stools, commencement of enteral nutrition, 30-d mortality, complications, postoperative pain, length of sick leave, rate of ventral hernia and the recurrence of small bowel obstruction during long-term follow-up as secondary and tertiary endpoints[44].

Laparoscopic adhesiolysis (Figure 6) for small bowel obstruction has a number of potential advantages including less postoperative pain, faster return of intestinal function, shorter hospital stay, reduced recovery time, allowing an earlier return to full activity, fewer wound complications, and decreased postoperative adhesion formation[45].

In a recent large population-based propensity score-matched analysis involving 6762 patients[46], laparoscopic treatment of ASBO was associated with lower rates of postoperative morbidity, including SSI, intraoperative transfusion, and overall lower resource use compared with laparotomy as well as shorter hospital stay. Laparoscopic treatment of surgical ASBO is not associated with a significant difference in operative time, rates of re-operation within 30 d, or mortality.

Further recent reports confirmed that laparoscopic surgical management of adhesive SBO is associated with quicker gastrointestinal recovery, shorter length of stay (LOS), and reduced overall complications compared to open surgery, without significant differences in operative times[47]. Furthermore, following exclusion of bowel resections, secondary outcomes continued to favor laparoscopy.

Although laparoscopic adhesiolysis requires a specific skill set and may not be appropriate in all patients, the laparoscopic approach demonstrates a clear benefit in 30-d morbidity and mortality even after controlling for preoperative patient characteristics (lower major complications and incisional complications rate) as well as shorter postoperative LOS and shorter mean operative times. Given these findings in more than 9000 patients and consistent rates of SBO requiring surgical intervention in the United States, increasing the use of laparoscopy could be a feasible way of to decrease costs and improving outcomes in this population[48].

Patient selection is still a controversial issue. From a recent consensus conference[49], a panel of experts recommended that the only absolute exclusion criteria for laparoscopic adhesiolysis in SBO are those related to pneumoperitoneum (e.g., hemodynamic instability or cardiopulmonary impairment); all other contraindications are relative and should be judged on a case-to-case basis, depending on the laparoscopic skills of the surgeon.

Nonetheless it is now well known that the immune response correlates with inflammatory markers associated with injury severity and, as a consequence, the magnitude of surgical interventions may influence the clinical outcomes through the production of molecular factors, ultimately inducing systemic inflammatory response and the beneficial effect of minimally invasive surgeries and of avoiding laparotomy is even more relevant in the frail patients[50].

Laparoscopic adhesiolysis is technically challenging, given the bowel distension and the risk of iatrogenic injuries if the small bowel is not appropriately handled. Key technical steps are to avoid grasping the distended loops and handling only the mesentery or the distal collapsed bowel. It is also mandatory to fully explore the small bowel starting from the cecum and running the small bowel distal to proximal until the transition point is found and the band/transition point identified. After release of the band, the passage into distal bowel is restored and the strangulation mark on the bowel wall is visible and should be carefully inspected.

As a precaution in the absence of advanced laparoscopic skills, a low threshold for open conversion should be maintained when extensive and matted adhesions are found[51].

Reported predictive factors for a successful laparoscopic adhesiolysis are: Number of previous laparotomies ≤ 2, non-median previous laparotomy, appendectomy as previous surgical treatment causing adherences, unique band adhesion as pathogenetic mechanism of small bowel obstruction, early laparoscopic management within 24 h from the onset of symptoms, no signs of peritonitis on physical examination, and experience of the surgeon[52].

Because of the consistent risks of inadvertent enterotomies and the subsequent significant morbidity, particularly in elderly patients and those with multiple (three or more) previous laparotomies, the lysis should be limited to the adhesions causing the mechanical obstruction or strangulation or those located at the transition point area; some authors have attempted to design a preoperative nomogram and a score to predict risk of bowel injury during adhesiolysis, and they found that the number of previous laparotomies, anatomical site of the operation, presence of bowel fistula and laparotomy via a pre-existing median scar were independent predictors of bowel injury[53,54].

Small bowel obstruction has been the driver of research in adhesion prevention measures, barriers and agents. Recent data from cohort studies and systematic reviews point at major morbidity and socioeconomic burden from adhesiolysis at reoperation, which have broadened the focus of adhesion prevention[55]. Applying adhesion barriers in two-stage liver surgery and cesarean section, to reduce the incidence of adhesions and adhesiolysis related complications, are examples of the change in paradigm that reducing the incidence of adhesions is clinically more meaningful than only aiming at preventing adhesive small bowel obstruction[56]. Increasing the number of patients without any peritoneal adhesion should be the general aim of adhesion prevention.

“Good” surgical technique and anti-adhesive barriers are the main current concepts of adhesion prevention. From a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on the impact of different surgical techniques on adhesion formation it was concluded that laparoscopy and not closing the peritoneum lower the incidence of adhesions[1].

However, the burden of adhesions in laparoscopy is still significant most likely due to the necessity to make specimen extraction incisions in addition to trocar incisions and the unavoidable peritoneal trauma by surgical dissection and the use of CO2 pneumoperitoneum (intraperitoneal pressure and desiccation). Reduced port laparoscopy and specimen extraction via natural orifices may theoretically further reduce peritoneal incision related adhesion formation[57].

Since all abdominal surgeries involve peritoneal trauma and potential healing with adhesion formation, additional measures are needed to reduce the incidence of adhesions and related clinical manifestations. These measures consist of systemic pharmacological agents, intraperitoneal pharmaceuticals or adhesion barriers[58]. Most clinical experience is with intraperitoneal adhesion barriers, applied at the end of surgery with the aim to separate injured peritoneal and serosal surfaces until complete adhesion free healing has occurred. Efficacy of anti-adhesion barriers in open surgery has been well established for reducing the incidence of adhesion formation[59]. For one type of barrier (Hyaluronate-carboxymethylcellulose, HA-CMC, Seprafilm, Sanofi, Paris, France) the reduction of incidence of adhesive small bowel obstruction after colorectal surgery has also been established (RR = 0.49, 95%CI: 0.28-0.88) without patient harm[59,60]. Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Interceed, Ethicon, West Somerville, NJ, United States) reduces the incidence of adhesion formation following fertility surgery (RR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.31-0.86), but the impact on small bowel obstruction after gynecological surgery has not been studied[59,61]. Drawback of both products is the difficulty to use in laparoscopic surgery, underlining the need to develop gel, spray or fluid barriers that are easy to apply via a trocar.

In the Prevention of Postoperative Abdominal Adhesions (P.O.P.A) study, authors randomized 91 patients to have 2000 cc of icodextrin 4% and 90% to have the traditional treatment. The authors noted no significant difference in the incidence of small bowel leakage or anastomotic breakdown; operative times, blood losses, incidence of small bowel resections, return of bowel function, LOS, early and late morbidity and mortality were comparable. After a mean follow-up of 41.4 mo, there have been 2 cases of ASBO recurrence in the icodextrin group and 10 cases in the control group (P < 0.05)[61].

Consistent safety and efficacy evidence has not led to routine application of barriers in open or laparoscopic surgery. Reasons might be the lack of awareness, the question if the “effect size” is large enough for routine application or the belief that adhesion formation even may benefit the patients, e.g., reinforcing intestinal anastomosis or walling off peritoneal infection. However, the most used argument against routine use is the doubt regarding cost-effectiveness of adhesion barriers. The direct hospital costs in the United States in 2005 for adhesive small bowel obstruction alone was estimated at $3.45 billion. Costs associated with the treatment of an adhesive SBO are estimated to be $3000 per episode with conservative treatment and $9000 with operative treatment. The additional costs incurred by operative treatment are partially due to complications of adhesiolysis. The incidence of bowel injuries during adhesiolysis for SBO is estimated to be between 6% and 20%. Inadvertent enterotomy due to adhesiolysis in elective surgery is associated with a mean increase in costs of $38000[58,61,62].

In a model, counted for in-hospital costs and savings resulting from adhesive SBO based on United Kingdom price data from 2007, Wilson showed that a low priced barrier at about $160 with 25% efficacy in preventing SBO would result in healthcare savings. Another concept with a $360 priced barrier, would result in a net investment on the long-term unless a higher efficacy of 60% could be achieved. In this model treatment costs for small bowel obstruction were substantially lower than more recent cost calculations. Recent direct healthcare costs associated with treatment of major types of adhesion related complications (small bowel obstruction, adhesiolysis complications and secondary female infertility) within the first 5 years after surgery are $2350 following open surgery and $970 after laparoscopy. Application of an anti-adhesion barrier could save between $678-1030 following open surgery and between $268-413 following laparoscopic surgery on the direct healthcare costs related to treatment of adhesion related complications (data not published). Benefits from reduction in SBO were $103 in open surgery and $32 in laparoscopic surgery, using a high ($360) priced product and only taken into account reoperations for adhesive small bowel obstruction. From these cost modeling it seems that even routine use of anti-adhesion barriers is cost-effective in both open and laparoscopic surgery[62-64].

Unfortunately, there are not yet devices able to totally prevent the intraperitoneal adhesion formation after abdominal surgery; only the use of correct surgical technique and the avoidance of traumatic intraperitoneal organ maneuvers may help to reduce postoperative adhesion incidence.

P- Reviewer: Catena F, Shehata MM S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | ten Broek RP, Issa Y, van Santbrink EJ, Bouvy ND, Kruitwagen RF, Jeekel J, Bakkum EA, Rovers MM, van Goor H. Burden of adhesions in abdominal and pelvic surgery: systematic review and met-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Loftus T, Moore F, VanZant E, Bala T, Brakenridge S, Croft C, Lottenberg L, Richards W, Mozingo D, Atteberry L. A protocol for the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:13-19; discussion 19-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | von Dembowski T. Über die Ursachen der peritonealen Adhäsionen nach chirurgischen Eingriffen mit Rücksicht auf die Frage des Ileus nach Laparotomien. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1889;37:745. |

| 4. | Millet I, Ruyer A, Alili C, Curros Doyon F, Molinari N, Pages E, Zins M, Taourel P. Adhesive small-bowel obstruction: value of CT in identifying findings associated with the effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment. Radiology. 2014;273:425-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Parker MC, Ellis H, Moran BJ, Thompson JN, Wilson MS, Menzies D, McGuire A, Lower AM, Hawthorn RJ, O’Briena F. Postoperative adhesions: ten-year follow-up of 12,584 patients undergoing lower abdominal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:822-829; discussion 829-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ellis H, Moran BJ, Thompson JN, Parker MC, Wilson MS, Menzies D, McGuire A, Lower AM, Hawthorn RJ, O’Brien F. Adhesion-related hospital readmissions after abdominal and pelvic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 1999;353:1476-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 651] [Cited by in RCA: 637] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Scott FI, Osterman MT, Mahmoud NN, Lewis JD. Secular trends in small-bowel obstruction and adhesiolysis in the United States: 1988-2007. Am J Surg. 2012;204:315-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Okabayashi K, Ashrafian H, Zacharakis E, Hasegawa H, Kitagawa Y, Athanasiou T, Darzi A. Adhesions after abdominal surgery: a systematic review of the incidence, distribution and severity. Surg Today. 2014;44:405-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Taylor GW, Jayne DG, Brown SR, Thorpe H, Brown JM, Dewberry SC, Parker MC, Guillou PJ. Adhesions and incisional hernias following laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer in the CLASICC trial. Br J Surg. 2010;97:70-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Isaksson K, Montgomery A, Moberg AC, Andersson R, Tingstedt B. Long-term follow-up for adhesive small bowel obstruction after open versus laparoscopic surgery for suspected appendicitis. Ann Surg. 2014;259:1173-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Di Saverio S, Catena F, Kelly MD, Tugnoli G, Ansaloni L. Severe adhesive small bowel obstruction. Front Med. 2012;6:436-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Eskelinen M, Ikonen J, Lipponen P. Contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and computer assistance to diagnosis of acute small-bowel obstruction. A prospective study of 1333 patients with acute abdominal pain. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:715-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jancelewicz T, Vu LT, Shawo AE, Yeh B, Gasper WJ, Harris HW. Predicting strangulated small bowel obstruction: an old problem revisited. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Derikx JP, Luyer MD, Heineman E, Buurman WA. Non-invasive markers of gut wall integrity in health and disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5272-5279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Block T, Nilsson TK, Björck M, Acosta S. Diagnostic accuracy of plasma biomarkers for intestinal ischaemia. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2008;68:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Evennett NJ, Petrov MS, Mittal A, Windsor JA. Systematic review and pooled estimates for the diagnostic accuracy of serological markers for intestinal ischemia. World J Surg. 2009;33:1374-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kanda T, Tsukahara A, Ueki K, Sakai Y, Tani T, Nishimura A, Yamazaki T, Tamiya Y, Tada T, Hirota M. Diagnosis of ischemic small bowel disease by measurement of serum intestinal fatty acid-binding protein in patients with acute abdomen: a multicenter, observer-blinded validation study. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:492-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jakob SM, Merasto-Minkkinen M, Tenhunen JJ, Heino A, Alhava E, Takala J. Prevention of systemic hyperlactatemia during splanchnic ischemia. Shock. 2000;14:123-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lange H, Jäckel R. Usefulness of plasma lactate concentration in the diagnosis of acute abdominal disease. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:381-384. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Shi H, Wu B, Wan J, Liu W, Su B. The role of serum intestinal fatty acid binding protein levels and D-lactate levels in the diagnosis of acute intestinal ischemia. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:373-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gerhardt RT, Nelson BK, Keenan S, Kernan L, MacKersie A, Lane MS. Derivation of a clinical guideline for the assessment of nonspecific abdominal pain: the Guideline for Abdominal Pain in the ED Setting (GAPEDS) Phase 1 Study. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:709-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Diagnostic imaging of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:452-459. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Di Saverio S, Tugnoli G, Orlandi PE, Casali M, Catena F, Biscardi A, Pillay O, Baldoni F. A 73-year-old man with long-term immobility presenting with abdominal pain. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mullan CP, Siewert B, Eisenberg RL. Small bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:W105-W117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jaffe TA, Martin LC, Thomas J, Adamson AR, DeLong DM, Paulson EK. Small-bowel obstruction: coronal reformations from isotropic voxels at 16-section multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2006;238:135-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Branco BC, Barmparas G, Schnüriger B, Inaba K, Chan LS, Demetriades D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic and therapeutic role of water-soluble contrast agent in adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2010;97:470-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Trésallet C, Lebreton N, Royer B, Leyre P, Godiris-Petit G, Menegaux F. Improving the management of acute adhesive small bowel obstruction with CT-scan and water-soluble contrast medium: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1869-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, Giorgio Rossi A, Romano L, Pinto F, Di Mizio R. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:5-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Di Saverio S, Catena F, Ansaloni L, Gavioli M, Valentino M, Pinna AD. Water-soluble contrast medium (gastrografin) value in adhesive small intestine obstruction (ASIO): a prospective, randomized, controlled, clinical trial. World J Surg. 2008;32:2293-2304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Galati M, Smerieri N, Biffl WL, Ansaloni L, Tugnoli G, Velmahos GC, Sartelli M, Bendinelli C. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2013 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Farid M, Fikry A, El Nakeeb A, Fouda E, Elmetwally T, Yousef M, Omar W. Clinical impacts of oral gastrografin follow-through in adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO). J Surg Res. 2010;162:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Leung AM, Vu H. Factors predicting need for and delay in surgery in small bowel obstruction. Am Surg. 2012;78:403-407. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Schraufnagel D, Rajaee S, Millham FH. How many sunsets? Timing of surgery in adhesive small bowel obstruction: a study of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:181-187; discussion 187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Diaz JJ, Bokhari F, Mowery NT, Acosta JA, Block EF, Bromberg WJ, Collier BR, Cullinane DC, Dwyer KM, Griffen MM. Guidelines for management of small bowel obstruction. J Trauma. 2008;64:1651-1664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Guo SB, Duan ZJ. Decompression of the small bowel by endoscopic long-tube placement. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1822-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Choi HK, Chu KW, Law WL. Therapeutic value of gastrografin in adhesive small bowel obstruction after unsuccessful conservative treatment: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2002;236:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Assalia A, Schein M, Kopelman D, Hirshberg A, Hashmonai M. Therapeutic effect of oral Gastrografin in adhesive, partial small-bowel obstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Surgery. 1994;115:433-437. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Abbas S, Bissett IP, Parry BR. Oral water soluble contrast for the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD004651. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Chen SC, Chang KJ, Lee PH, Wang SM, Chen KM, Lin FY. Oral urografin in postoperative small bowel obstruction. World J Surg. 1999;23:1051-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chen SC, Yen ZS, Lee CC, Liu YP, Chen WJ, Lai HS, Lin FY, Chen WJ. Nonsurgical management of partial adhesive small-bowel obstruction with oral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2005;173:1165-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Fukami Y, Kurumiya Y, Mizuno K, Sekoguchi E, Kobayashi S. Clinical effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in adhesive postoperative small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2014;101:433-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Duron JJ, Silva NJ, du Montcel ST, Berger A, Muscari F, Hennet H, Veyrieres M, Hay JM. Adhesive postoperative small bowel obstruction: incidence and risk factors of recurrence after surgical treatment: a multicenter prospective study. Ann Surg. 2006;244:750-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Li MZ, Lian L, Xiao LB, Wu WH, He YL, Song XM. Laparoscopic versus open adhesiolysis in patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2012;204:779-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Sallinen V, Wikström H, Victorzon M, Salminen P, Koivukangas V, Haukijärvi E, Enholm B, Leppäniemi A, Mentula P. Laparoscopic versus open adhesiolysis for small bowel obstruction - a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Surg. 2014;14:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Catena F, Di Saverio S, Kelly MD, Biffl WL, Ansaloni L, Mandalà V, Velmahos GC, Sartelli M, Tugnoli G, Lupo M. Bologna Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction (ASBO): 2010 Evidence-Based Guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lombardo S, Baum K, Filho JD, Nirula R. Should adhesive small bowel obstruction be managed laparoscopically? A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program propensity score analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:696-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Byrne J, Saleh F, Ambrosini L, Quereshy F, Jackson TD, Okrainec A. Laparoscopic versus open surgical management of adhesive small bowel obstruction: a comparison of outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2525-2532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kelly KN, Iannuzzi JC, Rickles AS, Garimella V, Monson JR, Fleming FJ. Laparotomy for small-bowel obstruction: first choice or last resort for adhesiolysis? A laparoscopic approach for small-bowel obstruction reduces 30-day complications. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:65-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Vettoretto N, Carrara A, Corradi A, De Vivo G, Lazzaro L, Ricciardelli L, Agresta F, Amodio C, Bergamini C, Borzellino G. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis: consensus conference guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e208-e215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Di Saverio S. Emergency laparoscopy: a new emerging discipline for treating abdominal emergencies attempting to minimize costs and invasiveness and maximize outcomes and patients’ comfort. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:338-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Catena F, Di Saverio S, Ansaloni L, Pinna A, Lupo M, Mirabella A, MandalàV . Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction. In Mandalà V. Updates in Surgery: The Role of Laparoscopy in Emergency Abdominal Surgery. Verlag Italia: Springer 2012; 89–104. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Farinella E, Cirocchi R, La Mura F, Morelli U, Cattorini L, Delmonaco P, Migliaccio C, De Sol AA, Cozzaglio L, Sciannameo F. Feasibility of laparoscopy for small bowel obstruction. World J Emerg Surg. 2009;4:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | ten Broek RP, Strik C, van Goor H. Preoperative nomogram to predict risk of bowel injury during adhesiolysis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:720-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Coccolini F, Ansaloni L, Manfredi R, Campanati L, Poiasina E, Bertoli P, Capponi MG, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, Cucchi M. Peritoneal adhesion index (PAI): proposal of a score for the “ignored iceberg” of medicine and surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | ten Broek RP, Strik C, Issa Y, Bleichrodt RP, van Goor H. Adhesiolysis-related morbidity in abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;258:98-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Robb WB, Mariette C. Strategies in the prevention of the formation of postoperative adhesions in digestive surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1228-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Moris DN, Bramis KJ, Mantonakis EI, Papalampros EL, Petrou AS, Papalampros AE. Surgery via natural orifices in human beings: yesterday, today, tomorrow. Am J Surg. 2012;204:93-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | ten Broek RP, Stommel MW, Strik C, van Laarhoven CJ, Keus F, van Goor H. Benefits and harms of adhesion barriers for abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;383:48-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hindocha A, Beere L, Dias S, Watson A, Ahmad G. Adhesion prevention agents for gynaecological surgery: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD011254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Bashir S, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, Burke WM, Lu YS, Neugut AI, Herzog TJ, Hershman DL, Wright JD. Utilization and safety of sodium hyaluronate-carboxymethylcellulose adhesion barrier. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1174-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Catena F, Ansaloni L, Di Saverio S, Pinna AD. P.O.P.A. study: prevention of postoperative abdominal adhesions by icodextrin 4% solution after laparotomy for adhesive small bowel obstruction. A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:382-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Ward BC, Panitch A. Abdominal adhesions: current and novel therapies. J Surg Res. 2011;165:91-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Wilson MS. Practicalities and costs of adhesions. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9 Suppl 2:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Parker MC, Wilson MS, van Goor H, Moran BJ, Jeekel J, Duron JJ, Menzies D, Wexner SD, Ellis H. Adhesions and colorectal surgery - call for action. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9 Suppl 2:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |