Published online Dec 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i12.779

Peer-review started: June 28, 2016

First decision: September 2, 2016

Revised: September 11, 2016

Accepted: October 5, 2016

Article in press: October 9, 2016

Published online: December 27, 2016

Processing time: 177 Days and 10.6 Hours

To investigate the assumption that schistosomiasis is the main cause of rectal prolapse in young Egyptian males.

Twenty-one male patients between ages of 18 and 50 years with complete rectal prolapse were included in the study out of a total 29 patients with rectal prolapse admitted for surgery at Colorectal Surgery Unit, Ain Shams University hospitals between the period of January 2011 and April 2014. Patients were asked to fill out a specifically designed questionnaire about duration of the prolapse, different bowel symptoms and any past or present history of schistosomiasis. Patients also underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy and four quadrant mid-rectal biopsies documenting any gross or microscopic rectal pathology. Data from questionnaire and pathology results were analyzed and patients were categorized according to their socioeconomic class.

Twelve patients (57%) never contracted schistosomiasis and were never susceptible to the disease, nine patients (43%) had history of the disease but were properly treated. None of the patients had gross rectal polyps and none of the patients had active schistosomiasis on histopathological examination. Fifteen patients (71%) had early onset prolapse that started in childhood, majority before the age of 5 years. Thirteen patients (62%) were habitual strainers, and four of them (19%) had straining dating since early childhood. Four patients (19%) stated that prolapse followed a period of straining that ranged between 8 mo and 2 years. Nine patients (43%) in the present study came from the low social class, 10 patients (48%) came from the working class and 2 patients (9%) came from the low middle social class.

Schistosomiasis should not be considered the main cause of rectal prolapse among young Egyptian males. Childhood prolapse that continues through adult life is likely involved. Childhood prolapse probably results from malnutrition, recurrent parasitic infections and diarrhea that induce straining and prolapse, all are common in lower socioeconomic classes.

Core tip: Rectal prolapse in Western countries is mainly a disease of old women but in Egypt, the incidence of complete rectal prolapse was found to be highest among young males. Previous studies have attributed this to proctosigmoiditis caused by schistosomiasis, which is endemic in many rural areas of Egypt, and to which young males are more susceptible. In this study we disprove this assumption and shed light on other factors related to socioeconomic status that are more likely to be the cause of this disease distribution in the population.

- Citation: Abou-Zeid AA, ElAbbassy IH, Kamal AM, Somaie DA. Complete rectal prolapse in young Egyptian males: Is schistosomiasis really condemned? World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(12): 779-783

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i12/779.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i12.779

Complete rectal prolapse is not uncommon. Unlike Western countries, the disease in Egypt predominantly affects young males. This has been attributed to intestinal schistosomiasis[1-3], a parasitic endemic disease in Egypt that predominantly affects young males causing periportal hepatic fibrosis, portal hypertension, and proctosigmoiditis. The latter is associated with thickening, edema and inflammation of the bowel wall as well as rectal inflammatory polyps, fibrosis and strictures. It has been postulated that the heavy weight of the rectum caused by rectal wall edema and polyps, the chronic dysentery and straining during defecation caused by rectal wall inflammation, and the pelvic floor myopathy caused by the general malnutrition that is frequently seen in schistosomiasis patients are the cause of complete rectal prolapse in this young Egyptian age group[1-3]. Despite those plausible explanations, it is not clear why complete rectal prolapse in Egypt is so infrequent when compared to other diseases associated with schistosomiasis such as liver cell failure, ascites, splenomegaly and hematemesis[4]. It is also not clear why other inflammatory and polypoidal diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis are not known to be associated with complete rectal prolapse. Finally, it is not clear why the significant reduction in the incidence of schistosomiasis in Egypt that resulted from the aggressive national program for eradication of the disease was not reflected in a similar decrease in the incidence or change in the pattern of rectal prolapse in this country[5,6]. The present study is trying to answer the question: Is schistosomiasis really condemned as a cause of complete rectal prolapse in young Egyptian males.

This prospective study included all male patients with complete rectal prolapse in the age group 18-50 years (n = 21, median age 23 years, range 18-45 years) who were admitted for surgery for their disease to the Unit of Colorectal Surgery, Ain Shams University Hospitals, Cairo, Egypt in the period between January 2011 and April 2014. Female patients in the same age group (n = 3), patients younger than 18 years (n = 2) or older than 50 years (n = 4) were excluded from the study.

All patients were requested to fill out a questionnaire about duration of the prolapse, different bowel symptoms and any past or present history of schistosomiasis. All patients had flexible sigmoidoscopy and four quadrant mid-rectal biopsies documenting any gross or microscopic rectal pathology. Patients were categorized according to their socioeconomic class (Table 1)[7].

| Class | Description |

| The lower class | Typified by poverty, homelessness, and unemployment Few individuals in this class finish their high school education They suffer from lack of medical care, adequate housing and food, decent clothing, safety, and vocational training |

| The working class | Minimally educated people who engage in “manual labor” with little or no prestige Unskilled workers in the class-dishwashers, cashiers, maids, and waitresses-usually are underpaid and have no opportunity for career advancement Skilled workers in this class-carpenters, plumbers, and electricians-may make more money than workers in the middle class, however, their jobs are usually more physically taxing, and in some cases quite dangerous |

| The middle class | Have more money than those below them on the “social ladder,” but less than those above them The lower middle class is often made up of less educated people with lower incomes, such as managers, small business owners, teachers, and secretaries The upper middle class is often made up of highly educated business and professional people with high incomes, such as doctors, lawyers, stockbrokers, and CEOs |

| The upper class | The lower-upper class includes those with “new money,” or money made from investments, business ventures, and so forth The upper-upper class includes those aristocratic and “high-society” families with “old money” who have been rich for generations. The upper-upper class is more prestigious than the lower-upper class Both segments of the upper class are exceptionally rich. They live in exclusive neighborhoods, gather at expensive social clubs, and send their children to the finest schools. As might be expected, they also exercise a great deal of influence and power both nationally and globally |

The nature and importance of the study were explained to all patients who were consented to participate in the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the IRB.

Twelve patients (57%) never contracted schistosomiasis and neither lived in a rural area nor worked in a job where they can come in contact with infested Nile water to contract the disease. Nine patients (43%) contracted the disease in the past and received timely proper treatment. None of the patients had gross polyps on sigmoidoscopy and none of the patients had evidence of active schistosomiasis on histopathology. The detailed gross and histopathology results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Gross pathology | n (%) |

| Normal mucosa | 10 (48) |

| Mucosal edema | 8 (38) |

| Fine mucosal granularity + small superficial ulcers | 3 (14) |

| Histopathology | n (%) |

| Normal mucosa | 8 (38) |

| Submucosal infiltration with chronic non-specific inflammatory cells | 8 (38) |

| Features of solitary rectal ulcer | 5 (24) |

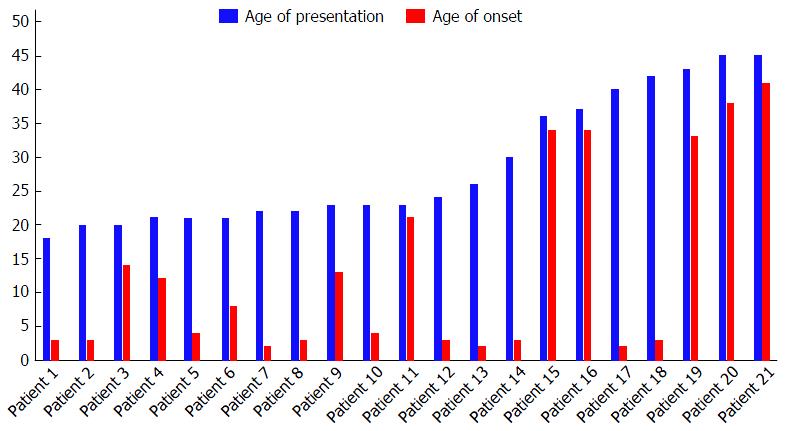

Fifteen patients (71%) had early onset prolapse that started in early childhood (age < 5 years) in 11, or in late childhood or early teen ages (age between 5 and 15 years) in 4. The duration of prolapse in those patients ranged between 3 and 40 years (median duration 15 years). The median age of presentation in this group was 21 years (range 18-42 years). Six patients had late onset prolapse that started to appear in late teen ages or adulthood. The duration of prolapse in those patients ranged between 6 mo and 10 years (median duration 2 years). The median age of presentation was 34 years (range 21-41 years) (Figure 1).

Thirteen patients (62%) were habitual strainers (9 patients with long duration prolapse and 4 patients with short duration prolapse). Four patients (19%) reported straining since early childhood and four (19%) stated that prolapse followed a period of straining that ranged between 8 mo and 2 years. Two chronic strainers had stool incontinence after long period of straining; one of them was a habitual strainer since early childhood. Seven patients had recurrent prolapse when they first presented to our institution. Five of those patients were habitual strainers and all did not stop straining after their previous non-resection surgery. Three patients stated that the prolapse followed an anal operation (haemorrhoidectomy in 2 patients and lateral sphincterotomy in one patient). Two of those patients were habitual strainers.

Nine patients (43%) in the present study came from the low social class, 10 patients (48%) came from the working class and 2 patients (9%) came from the low middle social class.

Complete rectal prolapse in Western countries occurs most commonly in elderly females, the disease being attributed to damage to the pudendal nerves during childbirth, prolonged straining at stool, and/or anatomical considerations such as a wider pelvis[8]. The majority of complete rectal prolapse in Egypt occurs in young males. Previous studies from this country attributed this young male preponderance to intestinal schistosomiasis with its associated proctosigmoiditis, the disease being prevalent in 30% to 81% of prolapse patients in those studies[1-3]. Unlike previous results, none of the patients in the present study had symptoms of active schistosomiasis at the time of presentation, none had gross polyps or dysentery and none had histologic evidence of schistosomiasis on rectal biopsies. Despite this, the majority of patients with rectal prolapse that we see in our institution are young males, implying that predisposing factors other than schistosomiasis must be involved.

In the present study, 71% of patients had childhood or early teen age prolapse that continued through adulthood, 81% were chronic strainers at stools, and 19% started straining in their early childhood. It is therefore likely that early childhood prolapse that continues through adulthood together with chronic straining during defecation are important factors that predispose to occurrence of rectal prolapse in young Egyptian males.

Childhood rectal prolapse is uncommon in Western countries. The disease is seen more frequently in poor and developing countries where it is predisposed to by malnutrition and inadequate food hygiene[9]. Malnutrition aggravates the natural laxity of the rectal pelvic supports that is present in infants and children, and inadequate food hygiene is associated with parasitic infections of the gastrointestinal tract and chronic diarrhea that induces excessive straining during defecation and rectal prolapse[10]. Enterobiasis, Amoebiasis, Shigellosis, Giardiasis and infection with Hymenolepis nana are all common parasitic diseases that have been reported to cause diarrhea and complete rectal prolapse in children in developing countries[11-13].

Even in developing countries, a group of countries in which Egypt is categorized, malnutrition and parasitic infections are diseases that mainly affect the lower socioeconomic classes[14,15]. Population coming from lower socioeconomic classes suffer from poverty, unemployment, lack of high school education, lack of medical care and lack of adequate housing and food (Table 1). Ninety one percent of patients in the present study came from the low and working socioeconomic classes. Those patients are thus likely brought up in an environment in which they were malnourished and had recurrent infectious diarrhea that caused straining and complete rectal prolapse which continued to their adult life. Indeed, complete rectal prolapse is almost never seen in this age group in upper middle and high social classes in Egypt. The importance of malnutrition, diarrhea and straining in causing complete rectal prolapse in children was clearly demonstrated during the 1994 crisis in Rwanda when a high incidence of full-thickness rectal prolapse was noted among the refugee children in the south-west of the country, the prolapses arose as a result of acute diarrheal illness superimposed on malnutrition and worm infestation[16].

Other factors that might contribute to occurrence of complete rectal prolapse in the lower social classes are the lack of medical care for the children and the lack of high school education of the parents, the former indicates that infectious diarrhea that affects the children is unlikely to be properly treated and the latter can be reflected in bad potty training that has been shown in many studies to predispose to straining during defecation and complete rectal prolapse[11,17].

Three patients in the present study had their prolapse after different anal operations. Probably the anal complaint in those patients was a result of straining and that they also had occult prolapse when they had their surgeries, the anal procedure just unveiled the occult prolapse. Indeed, two of those patients were chronic strainers.

Finally, we believe the high incidence of schistosomiasis in prolapse patients in previous studies from Egypt was a mere coincidence because those studies came from centers which drain rural northern delta regions where schistosomiasis is prevalent. Human infection with Schistosoma requires continuous contact with fresh Nile water where cercaria, a stage of Schistosoma life cycle, live and can infect man by penetrating his skin. This scenario essentially occurs in farmers living in rural Nile delta regions where they contact Nile water all the time during irrigation of their fields. The center in which the present study was performed is located in Cairo and it drains urban regions where schistosomiasis is non-existent. This can explain the low incidence of schistosomiasis in the present study.

Schistosomiasis should no longer be considered the main culprit for the unconventional distribution of rectal prolapse among young Egyptian males. Other factors related to socioeconomic status such as malnutrition, recurrent infectious diarrhea and bad toilet training result in habitual straining and hence increase incidence of childhood prolapse, which when combined with neglect of treatment result in continuance of the problem through adult life. We believe this to be the cause of the currently observed distribution of complete rectal prolapse in the population.

In Egypt, there is an abnormal distribution of rectal prolapse among young men although in Western countries the disease is usually more common in old women. Previous literature from the area has attributed this to the spread of schistosomiasis in rural areas of Egypt which causes proctosigmoiditis and hence-according to the literature - rectal prolapse.

There were several findings that brought doubt to this assumption; eradication programs that caused great reduction in schistosomiasis infection, didn’t similarly reduce the incidence of rectal prolapse and many of the patients with prolapse had no history of contracting schistosomiasis or even living in rural areas. This raised questions about the actual etiology for this distribution in Egypt.

Through analysis of history given by patients with rectal prolapse and assessment of possible risk factors, the authors found that socioeconomic status plays a great role in the epidemiological distribution of rectal prolapse among young males. Low socioeconomic status was associated with malnutrition, infectious diarrhea, bad toilet habits and neglect of proper treatment all of which contribute to the preponderance of rectal prolapse in this unusual subset of the population.

Identification of the actual factors causing rectal prolapse in young males is the first step in addressing the problem and directing efforts to improve conditions of lower social classes regarding sanitation, nutrition and proper treatment of various diarrheal illnesses. The authors have tried to shed some light on what the authors believe are the main causes of prolapse in young population and further studies are required in this area as proper management of etiological factors will reduce the incidence of the disease and its economic burden since young males are the main earners and source of income in many areas of Egypt.

Authors believe there is no unusual terminology that requires further description.

Nice paper, well written. Very “small subject” but relevant and well analysed and discussed.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bloemendaal ALA S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Abul-Khair MH. Bilhariziasis and prolapse of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1976;63:891-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aboul-Enein A. Prolapse of the rectum in young men: treatment with a modified Roscoe Graham operation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:117-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hussein AM, Helal SF. Schistosomal pelvic floor myopathy contributes to the pathogenesis of rectal prolapse in young males. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:644-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | El-Khoby T, Galal N, Fenwick A, Barakat R, El-Hawey A, Nooman Z, Habib M, Abdel-Wahab F, Gabr NS, Hammam HM. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in Egypt: summary findings in nine governorates. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:88-99. [PubMed] |

| 5. | El Khoby T, Galal N, Fenwick A. The USAID/Government of Egypt’s Schistosomiasis Research Project (SRP). Parasitol Today. 1998;14:92-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zaher T, Abdul-Fattah M, Ibrahim A, Salah H, El-Motyam M, Abdel-Dayem W, Refaey M, Current Status of Schistosomiasis in Egypt: Parasitologic and Endoscopic Study in Sharqia Governorate. Afro-Egypt J Infect Endem Dis. 2011;1:9-11. |

| 7. | Priest J, Carter S, Statt D. The influence of social class. In: Consumer behavior, Edinburgh Business School, Heriot-Watt University, revised edition 2013; 1-19. |

| 8. | Mills SD. Rectal prolapse. Beck DE et al (eds). The ASCRS manual of colon and rectal surgery, second edition, New York: Springer 2014; 595-609. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Siafakas C, Vottler TP, Andersen JM. Rectal prolapse in pediatrics. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1999;38:63-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eriksen CA, Hadley GP. Rectal prolapse in childhood--the role of infections and infestations. S Afr Med J. 1985;68:790-791. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fahmy MA, Ezzelarab S. Outcome of submucosal injection of different sclerosing materials for rectal prolapse in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:353-356. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Khan WA, Griffiths JK, Bennish ML. Gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal manifestations of childhood shigellosis in a region where all four species of Shigella are endemic. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abrar Ul Haq K, Gul NA, Hammad HM, Bibi Y, Bibi A, Mohsan J. Prevalence of Giardia intestinalis and Hymenolepis nana in Afghan refugee population of Mianwali district, Pakistan. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:394-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pollack CE, Cubbin C, Sania A, Hayward M, Vallone D, Flaherty B, Braveman PA. Do wealth disparities contribute to health disparities within racial/ethnic groups? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:439-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Beknazarova M, Whiley H, Ross K. Strongyloidiasis: A Disease of Socioeconomic Disadvantage. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:pii: E517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chaloner EJ, Duckett J, Lewin J. Paediatric rectal prolapse in Rwanda. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:688-689. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Severijnen R, Festen C, van der Staak F, Rieu P. Rectal prolapse in children. Neth J Surg. 1989;41:149-151. [PubMed] |