INTRODUCTION

Histoacryl glue therapy is licensed in the United Kindom for emergency treatment of bleeding varices. Its chemical composition is a monomer, n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, which polymerises into a solid mass in contact with ionic materials including water or blood. This obturates, or fills, the vascular lumen and also encourages local thrombosis. It is used first line in gastric and ectopic varices (for emergency haemostasis and secondary prophylaxis) and second line for oesophageal varices (where banding is not possible due to degraded oesophageal tissue or previous failed banding attempts). There is a solid evidence base to support the use of glue in gastric varices with numerous case series[1-8] and randomised controlled trials[9-13] indicating that efficacy of haemostasis is over 80%-90%. Data comparing gastric variceal glue injection with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) is relatively scarce. Lo et al[14] performed a prospective case controlled trial in patients who had presented with acute GV bleeding and who had been stabilised with vasoconstrictors and endotherapy (not glue). They found long term superiority for TIPSS in terms of rebleeding at 33 mo (11% vs 38%, P = 0.01), but equivalent survival. A retrospective study found fewer rebleeds in the TIPSS group at 6 mo (15% vs 30%, P = 0.005), but again no differences in survival. A cost analysis showed far higher resource implications for TIPSS [$4138 United States dollars ($3009-$8290 United States dollars)] for glue vs $11906 United States dollars ($8200-$16770 United States dollars)[15].

The use of glue in the oesophagus is more controversial, although one series by Cipolletta et al[16] reported good results in 133 patients who had primary oesophageal injection of undiluted glue. Glue has also been used successfully in babies and infants less than 2 years old[17].

TECHNIQUE

Histoacryl glue is commonly mixed with lipiodol which slows the polymerisation process, allowing more time for injection, and being radio-opaque also permits post-procedural radiological examination. Precise technique varies across units both nationally and internationally. At the authors’ centre 0.5 mL glue aliquots are mixed with 1 mL of lipiodol in small syringes. Saline can be injected into the variceal lumen initially to confirm an intra-luminal position at this point. Glue/lipiodol mixture is then injected 1.5 mL at a time, the number of syringes depending on the size of the varix. Further saline is injected which detaches the glue from the end of the needle and reduces the chance of tearing the glue through the variceal wall on removal of the needle. Some endoscopists prefer to inject glue as they leave the lumen, thus sealing the injection site and maintaining a view of the needle before withdrawing completely. The varix is observed, and it is not unusual to see some self-limiting bleeding through the injection site. Further injections are administered into different parts of the varix if necessary, the intention being to render the varix “solid”. This is determined by probing with varix with an injection needle (needle withdrawn). The role of endoscopic ultrasound in facilitating injection when the view is obscured by blood in the stomach, or to provide a more accurate assessment of vascularity during and after injection, has been explored[18]. Real-time fluoroscopy to assess for possible embolisation has also been described, but this is better suited to elective re-injection of gastric varices and less achievable in the emergent scenario[19].

Great care should be taken by staff when preparing the glue. Any contact with the sclera or cornea can cause permanent injury, so goggles or full face masks should be used, and protocol for eye-washing well rehearsed. Patients with iodine allergies cannot receive Lipiodol. Permanent damage can also be done to the endoscope if glue polymerises in the working channel. Before the injection needle is withdrawn through the instrument the needle lumen should be flushed thoroughly. Small residues of polymerised glue may be visible on the tip of the needle, but this does not usually cause a problem.

The ideal outcome after treatment of gastric varices is illustrated in Figure 1. An 85-year-old lady who presented with haematemesis and encephalopathy was found to have a fundal gastric varix with a red sign. It was injected with 3 mL × 1.5 mL aliquots of glue/lipiodol. A plain X-ray demonstrated a well circumscribed “clot” of glue in the fundus, with additional strands in oesophageal vessels above. At check endoscopy 7 d later the varix was smaller and appeared “safe”.

Figure 1 Endoscopic images of a gastric varix before and after glue therapy.

The varix has become smaller and is now firm when probed. The plain radiograph between demonstrates a radio-opaque deposit in the fundus of the stomach, due to lipiodol.

VASCULAR CONSIDERATIONS

The propensity for glue in its liquid phase to spread along vessels distal and proximal to the bleeding varix should be emphasised, as this is relevant to the phenomena of local venous thrombosis and distant embolization. Specific haemodynamic features of cirrhotic patients such as hyperdynamic circulation, presence of porto-systemic shunts and dilated pulmonary vessels may also be implicated in these events.

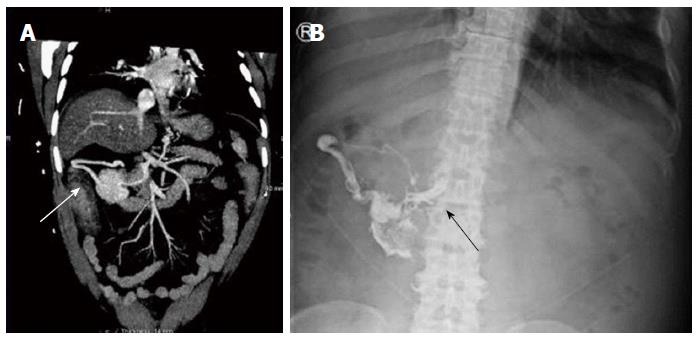

Figure 2 illustrates how glue can spread into feeding and draining vessels. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram (Figure 2A) performed on a cirrhotic patient who had a negative index endoscopy shows a large varix indenting the wall of the second part of duodenum, but without active extravasation. Figure 2B is a plain X-ray taken following injection of 9 mL histacryl glue into a large, actively bleeding duodenal varix that was identified at second endoscopy several hours later. A plain abdominal X-ray delineated the extent of lipiodol/histoacryl, which filled the varix and extended towards the portal vein, probably representing a dilated pancreato-duodenal vein. This patient recovered and experienced no adverse effects.

Figure 2 Duodenal varix on computed tomography and plain radiograph before and after glue injection.

A: Computed tomography angiogram showing a large abdominal varix meeting the duodenum (white arrow); B: After glue injection a plain radiograph showed lipiodol/glue in the same vessel, with extension medially up to the portal vein (black arrow).

In this review we categorise reported complications based on published reports, and will include illustrative examples of cases that the authors have been involved with.

COMPLICATIONS

Overview and incidence

Cheng et al[20], in a study focussed on complications, documented 51 adverse events in 753 treated patients (6.7%), 33 of these being early re-bleeds related to extrusion of glue within 3 mo. Overall complication related mortality was 0.53%. A study examining factors influencing outcomes (n = 90) found early complications in 14.4%, mostly infective and not clearly related to injection - however systemic embolisation occurred in 4.4%[5]. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, in its technical evaluation report of 2013[21], did not support the use of glue for oesophageal varices due to sporadic reports of complications. Embolisation is the most frequently mentioned complication during the consent process (author’s experience), a 1% risk being commonly quoted based on reviews which are explored below, but there is little certainty regarding other types of complications. Although most studies emphasise that the technique is safe, numerous reports describe unexpected early and delayed complications some of which are fatal.

Embolisation

A retrospective review looking at 25-year experience with glue injection by Saraswat et al[2] identified a risk of embolisation in the range 0.5%-4.3%. Cheng et al[20]’s large review of 753 cases identified distant embolisation in 5 patients (0.7%; 1 pulmonary, 1 brain, and 3 splenic). Fatal sepsis related to splenic infarction was reported in an isolated report[22].

Embolisation to the right atrium or pulmonary arteries has been reported by several authors[23-25], including one fatal case[26]. Chew et al[27] describe a patient who developed sudden hypoxia 10 d after injection. In this case solid particles must have become detached from the primary mass of glue. In contrast, the patient in whose care one of the authors was involved became hypoxic during the injection procedure and suffered runs of ventricular tachycardia which self-terminated. A post-procedural X-ray demonstrated glue in the pulmonary vasculature[23].

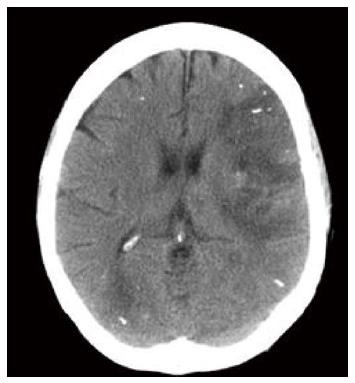

Cerebral embolisation has been reported several times. Upadhyay et al[28] described a patient who developed cortical blindness (as well as acute myocardial infarction), attributed to glue emboli. Sée et al[29] reported two cases of cerebral embolization (one fatal), and Roesch et al[30] reported simultaneous pulmonary, cerebral and coronary events. An intubated and ventilated patient one of the authors treated did not wake up appropriately following injection of a gastric varix. A CT scan of the brain revealed multiple peripheral radio-opaque deposits (Figure 3). An echocardiogram revealed an atrial septal defect, the likely explanation for cross over from the portal to the systemic arterial circulation, via the systemic venous return. The patient succumbed to multi-organ failure secondary to decompensated liver disease. In the absence of septal defects it is not easy to explain how glue moves into the systemic arterial circulation, but Sée et al[29] hypothesised that glue may travel via dilated pulmonary vessels which are known to develop in cirrhosis (associated with hepatopulmonary syndrome).

Figure 3 Computed tomogram of brain following glue/lipiodol injection.

There are high signal deposits peripherally following embolisation of glue.

Local venous thrombosis

Belletrutti et al[6] in their large review of patients in North America treated for gastric varices reported one case of superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. Mosca et al[7] reported one case of acute splenic vein thrombosis in their series of 65 patients treated for gastric varices. Liu et al[31] also reported splenic vein thrombosis in association with Klebsiella septicaemia. Shih et al[32] presented a case of portal vein thrombosis and progressive liver atrophy after cyanoacrylate injection. Shim et al[33] noted combined portal and splenic vein thrombosis in their report. Thrombosis of portomesenteric vessels is not surprising, given their proximity and intimate relation to porto-systemic collaterals that form oesophagogastric varices. Case reports have not described morbidity or mortality due to organ ischaemia secondary to vascular impingement, although experience would suggest new PVT can only be disadvantageous to cirrhosis patients.

Fistulisation and extravascular injection

Late fistulisation to a pulmonary vein following oesophageal injection was reported by Barclay et al[34]. This must have occurred following extra-vascular injection into the mediastinum. Retrogastric abscess formation following gastric variceal injection has been reported[35]. One of the authors has seen glue in the pleural space and in the para-oesophageal tissues (unpublished). In neither of these cases were there any short or medium term adverse consequences. The use of glue in refractory oesophageal variceal bleeding is more difficult and prone to inadvertent injection through the oesophageal wall into adjacent structures. Whereas gastric varices present an easily definable vessel, and the presence of the injection needle within the lumen can be confirmed with saline injections, oesophageal varices have usually been banded already and there may be considerable ulceration and mucosal trauma. Injections may be semi-blind or intended to enter intramural feeding vessels. Glue has also been used to “seal” the edges of post-banding ulcers that are found to be oozing. A report by Kim et al[36] described sinus formation after treatment for this indication.

Ulceration, erosion and extrusion

Choudhuri et al[3] identified ulceration of gastric varices in 32 of 170 injected patients, but did not attribute specific morbidity to this. Sharma et al[37] reported late bleeding from a glue ulcer. The authors’ experience suggests that ulceration is more troublesome after glue injection into the oesophagus, where extra-luminal injection is far more likely due to the difficultly in delineating the variceal columns. In one case, serial endoscopies identified increasing cavitation around a nidus of solid glue (Figure 4). This patient suffered ongoing decompensation and intermittent bleeding, dying from multiple organ failure two weeks after the initial treatment of bleeding. He was chronically encephalopathic and could not undergo TIPSS.

Figure 4 Endoscopic appearances of oesophagus following glue injection for refractory variceal haemorrhage.

There is ulceration and early cavitation in the first image which progresses and is severe 5 d later.

A large series (n = 168) reported by Wang et al[38] found early re-bleeding associated with “rejection” of glue in 9 (6.2%) at less than two months, and extrusion in a further 12 (8.1% at 2-18 mo). This study appeared to suggest that extrusion of glue casts into the gastric lumen is common, almost inevitable. There were cases of late re-bleeding, although persistent obturation of the variceal lumen was confirmed in the majority. The study of over 700 patients by Cheng et al[20] documented re-bleeding associated with “early extrusion” (i.e., less than 3 mo) in 33 (4.4%). One of these patients died.

Laceration of varix due to banding of an unrecognised glue deposit

One case report[39] has described inadvertent laceration of an oesophageal varix during band ligation, due to the presence of glue from a previous treatment session. This highlights the fact that glue is permanent, and it should be noted prior to future interventions.

Stricture

A single case of oesophageal impaction[40] following glue injection into a gastric varix was described over ten years ago.

Nidus of sepsis

There are several reports of chronic sepsis associated with glue, and a particular case reported by Wright et al[41] resulted in recurrent sepsis episodes with extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia following injection of a gastric varix. Imaging showed glue deposits in the fundal varix itself, the IVC and the left renal vein. The patient required 6 wk of parenteral antibiotic therapy before the sepsis was cleared. The case of splenic vein thrombosis reported by Liu et al[31] was associated with Klebsiella septicaemia. Hamad et al[42] described sepsis in association the embolic events, while Chang et al[43] identified portal vein thrombosis following injection as a source of continued sepsis.

CONCLUSION

The attractions of glue therapy include an evidence base for its efficacy, the ability to learn the technique by adapting common endoscopic skills, and the option to offer haemostatic therapy to patients who would otherwise require emergency transfer to a tertiary unit for consideration of TIPSS. Sadly, many patients are not candidates for TIPSS due to co-morbidity or the severity of liver failure, which leaves glue injection as the only remaining therapeutic option. Training in glue injection therapy is ad hoc, relying on the presence of trainees when patients present as emergencies. Planned glue sessions do occur, during following after treatment of large gastric varices, but the numbers are small.

Seewald et al[44] proposed several standardised steps, including dilution ratios, aliquot volumes and injection number. Agreed standards which include indications, recommended consent details and technical approach would ensure that trainees experience some consistency, would enlarge the foundation of experience on which informed consent is based and protect practitioners in the event of adverse outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Clinical observations contributing to this paper were made by the authors at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London; Kings College Hospital, London; Royal Free Hospital, London and Frimley Park Hospital, Surrey, all in the United Kingdom. The authors would like to thank Dr. Robert Barker, Consultant Radiologist, Frimley Park Hospital, for expert interpretation of radiological images in Figure 2.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Li Y, Samiullah S S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL