Published online Jul 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i7.110

Peer-review started: January 28, 2015

First decision: April 10, 2015

Revised: April 20, 2015

Accepted: May 16, 2015

Article in press: May 18, 2015

Published online: July 27, 2015

Processing time: 180 Days and 18.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the efficacy of a novel intraoperative diagnostic technique for patients with preliminary diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP).

METHODS: Patients with pancreatic surgery were reviewed to identify those who received a preliminary diagnosis of AIP between January 2010 and January 2014. The following data were collected prospectively for patients with a pathological diagnosis of AIP: clinical and demographic features, radiological and operative findings, treatment procedure, and intraoperative capillary refill time (CRT) in the pancreatic bed.

RESULTS: Eight patients (six males, two females; mean age: 51.4 years) met the eligibility criteria of pathologically confirmed diagnosis. The most frequent presenting symptoms were epigastric pain and weight loss. The most commonly conducted preoperative imaging studies were computed tomography and endoscopic retrograde pancreaticodoudenography. The most common intraoperative macroscopic observations were mass formation in the pancreatic head and diffuse hypervascularization in the pancreatic bed. All patients showed decreased CRT (median value: 0.76 s, range: 0.58-1.35). One-half of the patients underwent surgical resection and the other half received medical treatment without any further surgical intervention.

CONCLUSION: This preliminary study demonstrates a novel experience with measurement of CRT in the pancreatic bed during the intraoperative evaluation of patients with AIP.

Core tip: Autoimmune pancreatitis is still a diagnostic dilemma, and there is a way to go, especially differentiating from pancreatic malignancy. Hence the debate: to cut or to observe. We hypothesized that this infrequent inflammatory event causes increased vascularity on pancreatic tissue. Thus, we aimed to display whether there was a remarkable vascularity on the pancreatic surface or not by using capillary refill time. Preliminary results showed decreased capillary refill time demonstrating hypervascularity on the pancreatic surface and this inspired that capillary refill time could be an additional tool to guide the operational decision-making process of autoimmune pancreatitis.

- Citation: Yazici P, Ozsan I, Aydin U. Capillary refill time as a guide for operational decision-making process of autoimmune pancreatitis: Preliminary results. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(7): 110-115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i7/110.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i7.110

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is clinically defined as chronic inflammatory pancreatitis with irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct, presenting with hyperglobulinaemia (especially IgG4)[1,2]. Since its first description[3], this infrequently recognized pathology has posed a diagnostic dilemma; its initial clinical symptoms are generally non-specific (abdominal pain, weight loss and obstructive jaundice) and commonly lead to a misdiagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

Differentiating AIP from malignant pathology in the pancreas requires some clinical judgment in assessing the findings of the diagnostic workup and can be dependent upon the treating physician’s surgical experience with both conditions. Although imaging methods, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endosonography could provide differential findings, the accuracy is not consistent among all patients. Furthermore, there are many pitfalls in the frozen section diagnosis of pancreatic lesions and AIP patients may remain undiagnosed, so that sometimes, experience of the surgeon can play a remarkable role in determination of which management strategy will be performed.

Intraoperative observations may be useful for diagnosing AIP and determining the approach best suited for clinical management of a particular case; for example, surgeons may use macroscopic observations, such as that of a tumoral mass, to differentiate pancreatic cancer from AIP, and consider a pancreatoduodenectomy as treatment. However, it is important to remember that at least 5% of patients undergoing surgery for a preliminary diagnosis of pancreatic cancer are found to have benign inflammatory disease according to their histopathological findings[4]. Although a few policies have been published to help guide the surgeon’s decision for managing such borderline cases, this entity remains a diagnostic challenge in general.

For the current study, we were inspired by the inflammatory nature of AIP pathology to investigate whether there is an association between changes in the pancreatic vascular pattern in patients with AIP, and whether such an association would be related to a measurable increase in blood flow in the pancreatic bed due to ongoing inflammation. We hypothesized that such an increase (reflective of the circulatory status) may be measurable as capillary refill time (CRT). Thus, this preliminary report presents our initial experience with measurement of CRT in the pancreatic bed during the intraoperative evaluation of patients with AIP.

For this study, the medical records of patients undergoing pancreatic surgery were searched to identify patients who received a preliminary diagnosis of AIP between January 2010 and January 2014. All patients provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment and were consented for surgical procedure, as well. Those patients with a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of AIP were selected for study inclusion. All data recorded prospectively were retrieved from an IRB approved database. Clinical and demographic features of the patients, diagnostic methods and radiological findings, intraoperative observations, surgical procedures and outcomes were analyzed. Although systemic disease was investigated in three cases, increased IgG4 levels was detected in only one patient.

A single clinician using the following procedure made all measurements of CRT: First, the patient’s core temperature was evaluated (nasopharynx, normal range: 36.5 °C-37.5 °C) and proper thermoregulation was ensured. Then, the CRT was determined by pressing a gloved finger against the pancreatic surface, particularly on the most vascularized portion, until the region turned white (pressing time ranged between 4 and 7 s). The finger pressure was then fully released and the time it took for the pancreatic surface to return to its previous color was measured to the nearest second using a chronometer (generally carried out by the anesthesia care team). None of the patients received inotropic agents at the time of the CRT measurement. Each patient’s vital signs were recorded during the CRT measurement; in the case of abnormal vital signs, treatment was immediately initiated to restore the hemodynamic profile, after which a repeat measurement was taken. The normal values for CRT are well established and defined as < 2 s, with prolonged refill defined as ≥ 2 s. A digital video camera was used to record the CRT during the operation, and the study investigators reviewed the recorded tape, along with use of a chronometer, to confirm the recorded CRT measurement.

The criteria used by the surgical team to determine whether resection should be performed were standardized and included suspicious findings from endoscopic ultrasound (EU)-guided biopsy, malignant cells detected by frozen section assessment, older age (which increases the possibility of malignancy), and severe obstruction of the common bile duct (CBD) that could not be managed by endoscopic retrograde pancreaticoduodenography (ERCP).

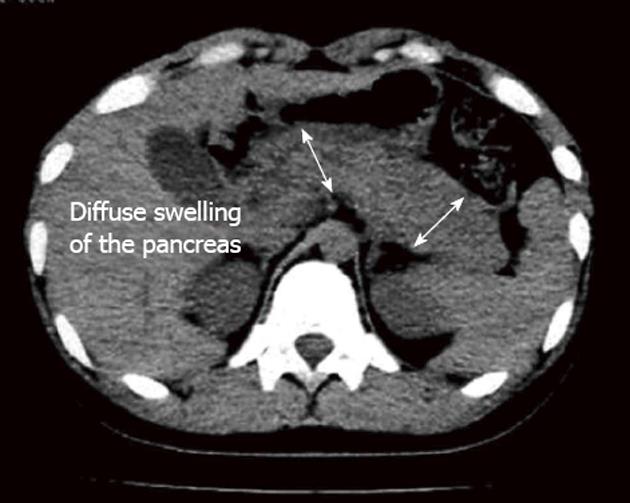

Eight patients with pathologically diagnosed AIP were included in the study; this group was composed of two females and six males, with a mean age of 51.4 years (range: 34-69 years). The duration of symptoms ranged from 2 wk to 3 mo, and the most frequent presenting symptoms were epigastric pain and weight loss. All patients showed mildly elevated levels of liver function enzymes. Among the three patients examined for IgG level, only one (patient 4) showed an elevated level. The methods of and findings from preoperative imaging studies are shown in Table 1. For patient 2, the CBD cannulation failed during ERCP and the pancreatic mass was observed to have invaded the superior mesenteric vein. Patients 3 and 8 also underwent ERCP, to address the CBD dilatation and relieve the obstruction. For some patients, the CT scan revealed diffuse swelling of the pancreatic tissue (Figure 1). The tumor masses were most frequently located in the pancreatic head (6/7 cases). EU-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was performed in two patients, with both cases showing non-specific inflammatory changes.

| Sex | Age (yr) | Presentation | Diagnostic tests | Findings | CRT (s) | Surgery |

| Patient 1, F | 69 | Jaundice, epigastric pain | Doppler US, CT | 4 cm × 4 cm solid mass, Pancreatic head, LAPs | 0.80 | PPPD |

| Patient 2, M | 61 | Epigastric pain, weight loss, jaundice | ERCP, CT | Pancreatic head mass (4 cm × 3 cm), obstruction of the CBD, invasion of SMV | 1.35 | PPPD |

| Patient 3, M | 34 | Jaundice, pruritis, fatigue | ERCP, CT | Periampullary solid mass 2 cm × 3 cm in size | 0.68 | Biopsy |

| Patient 4, M | 56 | Fatty stool, epigastric pain, weight loss | Doppler US, PET-CT | Diffuse swelling of the pancreas | 0.58 | Biopsy |

| Patient 5, M | 42 | Epigastric pain, weight loss, fatty stool | Doppler US, CT, EU | Periampullary solid mass (2 cm × 2 cm) | 0.75 | Biopsy |

| Patient 6, F | 58 | Mild epigastric pain, weight loss | CT, MRI, | Diffuse swelling and 2 cm × 2.5 cm solid mass in pancreatic head | 0.77 | PPPD |

| Patient 7, M | 45 | epigastric and back pain, weight loss | CT, MRI, EU | Diffuse swelling and mass formation 2 cm × 3 cm in size | 0.69 | Biopsy |

| Patient 8, M | 53 | Epigastric pain, weight loss, jaundice | ERCP, MRI | Pancreatic head mass (3 cm × 3 cm), obstruction of the CBD | 1.26 | PPPD |

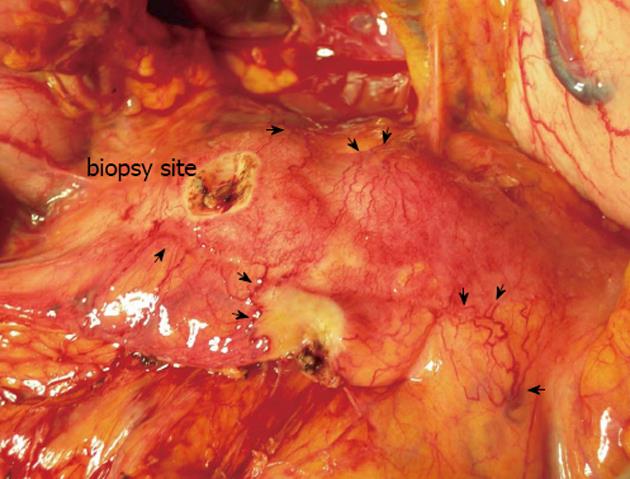

For all patients, the intraoperative macroscopic pancreas assessment revealed diffuse hypervascularization (Figure 2). The median CRT was 0.76 s (range: 0.58-1.35 s). Six patients had a CRT of < 1 s, with four of those patients undergoing only a biopsy before the surgical procedure was suspended. Five patients had inconclusive findings of malignancy from the histological analysis of the frozen section biopsy specimens, while four of these patients had findings compatible with inflammatory changes. When the surgical team considered the accumulated findings from each patient’s preoperative work-up along with their intraoperative findings, surgical resection (pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy) was carried out for one-half of the patients (4/8 cases; Table 1).

All patients experienced an uneventful postoperative recovery. Patients who underwent biopsy only (without further surgery) were administered corticosteroids on a 3-wk 1 mg/kg course followed by a life-long 5 mg maintenance course. In all patients but one, the medical treatment led to symptom improvement. Any patient required pain management was referred to an algologist. The mean follow-up period was 26.4 mo, during which none of the cases showed signs of malignancy. In addition, none of the patients who underwent pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy showed symptomology or abnormal findings related to other organ systems, leading to their classification as type 2 AIP cases.

We investigated the clinical importance of CRT measurement for patients with a prediagnosis of AIP. In these patients, a decreased CRT was found as an operative observation when the cut-off value of 2 s was used. Half of the patients underwent surgical resection (in accordance with the criteria explained in Methods section). It is well-known that not all pathologically diagnosed AIP cases have preoperative findings consistent with the set of specifications and criteria in the literature, highlighting the clinical dilemma facing physicians treating this disease[5]. In particular, AIP patients present with remarkable variation and no single diagnostic test has been established as the gold standard[6,7].

In the present study, preoperative diagnostic work-up, including imaging methods such as CT, MRI and EU, were not adequate to establish a definitive diagnosis. It is possible that the technical limitations of EU related to tissue sampling, particularly when the head of the pancreas is involved[8], may explain the inadequacy of this method in diagnosing our AIP cases. Moreover, the negative predictive value of EU-guided FNAB for pancreatic cancer has been reported as about 75%[9,10]. However, the focal type of AIP that the majority of our patients were ultimately diagnosed with also presented a diagnostic challenge for ERCP, emphasizing the technical difficulty in diagnosing this condition prior to surgery.

Dominance of elderly patients among AIP cases and presentation with severe jaundice contribute to the diagnostic difficulty or misdiagnosis of AIP[11,12]. Although the clinical manifestation of AIP may vary from patient to patient, most cases mimic the symptoms of pancreatic cancer. Hence, the high suspicion of malignancy leads treating physicians to prefer surgical removal as the treatment, particularly for patients with focal AIP. It is important to note that the case series reported herein included only AIP cases for whom the decision to perform surgery had already been made due to suspicion of malignancy or obstructive pathology which were deemed inappropriate for conservative management. Surgeons frequently need more information, apart from laboratory and radiological findings, demonstrating diffuse enlargement or focal masses in the pancreas, to diagnose AIP[11,13,14]. Therefore, we suggest that some intraoperative findings may help to guide the operational decision-making process.

The “inflammatory hypervascularization” character of the pancreas in AIP was the basis of our hypothesis and CRT was used in our study to evaluate this entity. Findings from this study demonstrated increased blood flow in response to the existing inflammation and subsequent decrease in CRT. It is well known that both malignant and benign pancreatic tissues may be reflected by changes in the vascularization patterns. Central hypervascularization caused by increased flow in the main artery of the organ or local neovascularization is more likely to be present in malignant lesions. However, a carcinoma may also present hypovascularization as desmoplastic changes and vascular encasement leading arterial stenosis or obstruction[15]. On the contrary, benign lesions, especially in inflammatory conditions, increase the propensity to develop diffuse hypervascularization and the capillary flow rate increases due to the associated increase in metabolic activity. Likewise, Hocke et al[16] reported that contrast-enhanced EU shows hypervascularization of AIP lesions, whereas pancreatic cancer lesions appear to be more hypovascular masses. In this study, diffuse hypervascularization was observed along the anterior surface of the pancreatic body and confirmed by the CRT measurements. With regard to the CRT results, all cases in our series were diagnosed with a value lower than the normal range reported in the literature. The normal value for CRT should be 2 s[17,18] and, on average, CRT increases 3.3% per decade increase in age. The median CRT for pediatric patients is 0.8 s, while that of adults is 1.0 to 1.5 s[19]. In our case series, the average CRT was 0.76 s.

Most of the focal AIP cases reported in the literature have been diagnosed only when swelling has become diffuse or after surgical observation[20]. In our case series, the definitive diagnosis was achieved according to accumulated findings from histological analyses of frozen section specimens, CRT, the intraoperative observations of pancreatic vascular pattern (particularly diffuse peripheral hypervascularization), and pathological findings (periphlebitis, dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltration, and/or fibrotic changes). For four of our cases, the surgery was halted due to pathological confirmation of notable inflammatory changes and markedly decreased CRT; consequently, each case was referred for non-surgical medical treatment.

Several limitations to our study design exist and must be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the small sample size (eight cases) prevented us from establishing a significant causal relation between decreased CRT and AIP; a comparative study between suspected AIP patients and those with definitive pancreatic cancer might allow strong conclusions to be drawn. Second, the CRT measurement was made using a chronometer and based on visual inspection; this measurement may be more accurate using a standardized method, such as digitalized CRT techniques. Intraoperative ultrasonography-based elastography is an emerging concept and may be also useful in addressing this clinical dilemma. However, this study aimed to describe CRT as an additional tool to lead surgeon to examine the patient for possibility to have AIP in the light of the surgeon’s experience and intraoperative observations.

This paper demonstrates preliminary results of a novel experience with measurement of CRT in the pancreatic bed during intraoperative evaluation of patients with AIP. The main finding of this prospective analysis of patients with a prediagnosis of AIP is that changes in macroscopic vascular pattern and decreased CRT, in conjunction with frozen section analysis, can help to guide the treatment approach. Large-scale clinical trials are needed to determine its role in clinical decisions making for this very complicated entity.

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) remains a diagnostic challenge for both clinicians and surgeons. Differentiating AIP from malignant pathology in the pancreas requires some clinical judgment in assessing the findings of the diagnostic workup and can be dependent upon the treating physician’s surgical experience with both conditions.

The authors aimed to introduce a novel intraoperative diagnostic technique for patients with preliminary diagnosis of AIP.

This preliminary study demonstrating a novel experience with measurement of capillary refill time in the pancreatic bed during the intraoperative evaluation of patients with AIP provided a decreased capillary refill time which can be attributable to hypervascularity.

Hypervascularization of AIP lesions radiologically inspired us to investigate the efficacy of this feature. It was evaluated by measurement of capillary refill time in the operating theatre. Preliminary results showed that it can be an additional tool in the surgical decision-making process.

Pancreatic hypervascularity: increased vascular web secondary to pancreatic inflammation; Capillary refill time: the time taken for color to return to an external capillary bed after finger pressure is applied to cause blanching on pancreatic tissue.

An interesting novel method of assessing of this difficult pancreatic condition. The paper will be of interest to our readers interested in pancreatic problems.

P- Reviewer: Munoz M, Seow-Choen F, Tandon R, Yang F S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yan JL

| 1. | Kawaguchi K, Koike M, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Tabata I, Fujita N. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with cholangitis: a variant of primary sclerosing cholangitis extensively involving pancreas. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:387-395. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Sarles H, Sarles JC, Camatte R, Muratore R, Gaini M, Guien C, Pastor J, Le Roy F. Observations on 205 confirmed cases of acute pancreatitis, recurring pancreatitis, and chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1965;6:545-559. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Sarles H, Sarles JC, Muratore R, Guien C. Chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas--an autonomous pancreatic disease? Am J Dig Dis. 1961;6:688-698. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | van Gulik TM, Reeders JW, Bosma A, Moojen TM, Smits NJ, Allema JH, Rauws EA, Offerhaus GJ, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Incidence and clinical findings of benign, inflammatory disease in patients resected for presumed pancreatic head cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:417-423. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Ikeura T, Detlefsen S, Zamboni G, Manfredi R, Negrelli R, Amodio A, Vitali F, Gabbrielli A, Benini L, Klöppel G. Retrospective comparison between preoperative diagnosis by International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria and histological diagnosis in patients with focal autoimmune pancreatitis who underwent surgery with suspicion of cancer. Pancreas. 2014;43:698-703. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Ikeura T, Manfredi R, Zamboni G, Negrelli R, Capelli P, Amodio A, Caliò A, Colletta G, Gabbrielli A, Benini L. Application of international consensus diagnostic criteria to an Italian series of autoimmune pancreatitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:276-284. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Wu G, Li X, Wang T, Zhang Q, He H, Sun M, Liu Y. Review of 43 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis based on the international consensus diagnostic criteria in China. Pancreas. 2014;43:810-811. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ. Endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in the evaluation of pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1386-1391. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Bang SJ, Kim MH, Kim do H, Lee TY, Kwon S, Oh HC, Kim JY, Hwang CY, Lee SS, Seo DW. Is pancreatic core biopsy sufficient to diagnose autoimmune chronic pancreatitis? Pancreas. 2008;36:84-89. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Binmoeller KF, Rathod VD. Difficult pancreatic mass FNA: tips for success. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S86-S91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Okazaki K, Chiba T. Autoimmune related pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;51:1-4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Okazaki K, Uchida K, Chiba T. Recent concept of autoimmune-related pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:293-302. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Ohana M, Okazaki K, Hajiro K, Kobashi Y. Multiple pancreatic masses associated with autoimmunity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:99-102. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Toki F, Kozu T, Oi I. An unusual type of chronic pancreatitis showing diffuse irregular narrowing of the entire main pancreatic duct on ERCP - a report of four cases. Endoscopy. 1992;640. |

| 15. | Koito K, Namieno T, Nagakawa T, Morita K. Inflammatory pancreatic masses: differentiation from ductal carcinomas with contrast-enhanced sonography using carbon dioxide microbubbles. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1263-1267. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hocke M, Ignee A, Dietrich CF. Three-dimensional contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound for the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E381-E382. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Anderson B, Kelly AM, Kerr D, Clooney M, Jolley D. Impact of patient and environmental factors on capillary refill time in adults. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:62-65. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wakabayashi T, Kawaura Y, Satomura Y, Watanabe H, Motoo Y, Okai T, Sawabu N. Clinical and imaging features of autoimmune pancreatitis with focal pancreatic swelling or mass formation: comparison with so-called tumor-forming pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2679-2687. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Beecher HK, Simeone FA. The internal state of the severely wounded man on entry to the most forward hospital. Surgery. 1947;22:672-711. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Hannan DS, Lepper RL, Atzinger ES, Copes WS, Prall RH. Assessment of injury severity: the triage index. Crit Care Med. 1980;8:201-208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |