Published online Mar 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i3.39

Peer-review started: October 18, 2014

First decision: November 27, 2014

Revised: December 28, 2014

Accepted: January 30, 2015

Article in press: February 2, 2015

Published online: March 27, 2015

Processing time: 165 Days and 11.8 Hours

Malignant ascites is a common symptom in patients with peritoneal cancer. Current assumption is that an increased vascular permeability and obstruction of lymphatic channels lead to the accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity. This case report describes a severely symptomatic patient with malignant ascites. The previously healthy 73-year-old male was presented with abdominal distention causing respiratory distress. Computed tomography revealed large amounts of ascites, a recto-sigmoidal mass with locoregional lymphadenopathy and an omental cake. Biopsy taken during colonoscopy revealed an adenocarcinoma of the colon with signet cell differentiation. A widespread peritoneal carcinomatosis was found during a diagnostic laparoscopy. The extent of peritoneal disease rendered the patient not suitable for cytoreductive surgery with curative intent. The ascites proved to be refractory to ultrasound-guided paracentesis; thus, a decision was made to perform palliative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy without cytoreductive surgery. Consequently, ascites production stopped, and the respiratory distress was relieved thereafter. The postoperative recovery was uneventful. Ascites recurred eight months later, and a second hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy procedure was performed. The patient was still alive at the time of writing, 16 mo after the initial diagnosis.

Core tip: Malignant ascites can cause debilitating symptoms in patients with peritoneal cancer. This report describes a patient with severe respiratory distress caused by malignant ascites from peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis. The patient was successfully treated with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy without cytoreductive surgery. Our results suggest that hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy without cytoreductive surgery should be considered in patients with symptomatic ascites, even when their prognosis is dismal.

- Citation: Houten MMLVD, Oudheusden TRV, Luyer MDP, Nienhuijs SW, Hingh IHJT. Respiratory distress due to malignant ascites palliated by hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(3): 39-42

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i3/39.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i3.39

Malignant ascites (MA) is a pathologic accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity caused by intraperitoneal disseminated cancer cells[1,2]. About 40% of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) secondary to colorectal cancer (CRC) develop MA[3]. In these patients, progressive abdominal distention eventually causes debilitating symptoms such as pain, nausea, anorexia, vomiting, and fatigue. In addition, ascites may hinder patients’ breathing, causing dyspnea[4]. The presence of MA is considered to be a grave prognostic sign, and in many patients, treatment is aimed only at palliation of symptoms. However, the first-line therapy with diuretics and paracentesis has shown varying efficacy[1,2]. Consequently, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has been advocated as an alternative treatment for refractory ascites[5-8].

The current report describes a patient with severe respiratory distress caused by MA from peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis. The patient was successfully palliated using HIPEC.

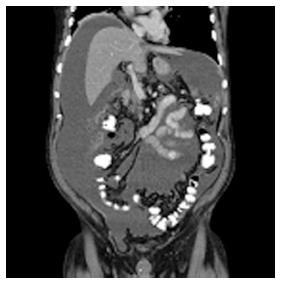

A previously healthy 73-year-old man was admitted to a regional hospital with a 3-wk history of debilitating abdominal distention, obstipation, dyschezia, anorexia, and dyspnea. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed large amounts of ascites (Figure 1), a large rectosigmoidal mass with locoregional lymphadenopathy, and an omental cake, but no systemic metastases. These findings were highly suggestive of PC of colonic cancer. Biopsies taken during the colonoscopy confirmed the presence of a mucinous adenocarcinoma in the proximal rectum.

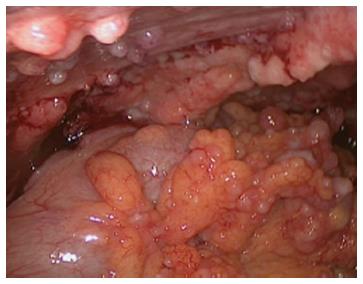

At the time of referral to our hospital, the patient was wheelchair bound and short of breath. A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed in order to determine the possibility of HIPEC with curative intent. The results revealed widespread peritoneal metastases (Figures 2 and 3) affecting all abdominal regions, adding up to a peritoneal cancer index of 34. Radical resection of all metastases was deemed impossible, disqualifying the patient from HIPEC with curative intent. To alleviate symptoms, 10 L of ascitic fluid was drained, and a colostomy was performed for fecal diversion. The patient felt immediate relief, but a day later, recurrent fluid production caused severe respiratory distress. An ultrasound-guided paracentesis was performed, temporarily alleviating symptoms. However, ascites production remained unmanageable with the production rate of 10 L every 24 h. In an effort to stop the ascites production, a laparoscopic HIPEC without cytoreductive surgery, was performed. Saline was heated to 41–42 °C and perfused intra-abdominally, followed by administration of mitomycin C (35 mg/m2) circulating for 90 min. Postoperatively, the peritoneal cavity was drained with three catheters that were removed 48 h after surgery as per protocol. The postoperative stay was uneventful, and the patient was discharged after 12 d. The malignant ascites and resulting symptoms disappeared. Subsequent pathologic investigation confirmed the presence of a mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet cell differentiation in the peritoneal deposits.

Palliative chemotherapy (FOLFOX/bevacizumab) was started four weeks later. Recurrent ascites occurred 8 mo after the HIPEC. Ultrasound-guided paracentesis provided insufficient relief. Given the positive response to the initial HIPEC, this procedure was repeated with oxaliplatin as the intraperitoneal agent. The patient was still alive 16 mo after the diagnosis and continues to receive palliative chemotherapy.

Approximately 10% of CRC patients develop peritoneal cancer in the course of their disease[9]. In a select group of patients, cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC are the treatment modality of choice, which offer long-term survival, or in some cases, a cure[10]. These results can only be achieved when complete cytoreduction of all visible tumors is obtained[9]. Consequently, patients unfit for major surgery, with systemic metastases or wherein complete cytoreduction cannot be achieved, have a dismal prognosis. In these patients, treatment is aimed at palliation of symptoms, including those caused by ascites.

MA is a common symptom in patients with PC[1-3]. The pathophysiology of MA is multi-factorial and remains to be fully elucidated. The current view is that an increased vascular permeability and obstruction of lymphatic channels lead to the accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity[1,2,11,12]. Ultrasound-guided paracentesis and fluid analysis are used to distinguish a benign origin from a malignant cause. CT may aid in the diagnostic work-up and reveal the primary source of malignancy[2].

Several palliative treatment modalities can be used in the management of MA. Paracentesis alleviates abdominal distention and subsequent symptoms, yet improvements are short-lived, as ascites often reaccumulates within 72 h, as was the case in our report[2]. Diuretic therapy appears to be effective in controlling MA when the serum-ascites albumin gradient is > 1.1 g/dL[13]. Although diuretic therapy has been effective in patients with ascites due portal hypertension secondary to liver metastases, its use in patients with PC is likely to be less effective[14]. Systemic chemotherapy for the treatment of ascites in CRC patients has not yet been assessed. However, MA usually presents itself in the terminal stage of disease when available chemotherapeutic regimens have already been deployed[1]. Therefore, systemic chemotherapy is likely to play a minor role.

In patients with MA refractory to the first-line treatment modalities, HIPEC may provide symptomatic relief. In a case series by Valle et al[6], 52 patients with PC-related ascites were treated with palliative HIPEC without cytoreductive surgery. This strategy appeared to be successful in all but one patient. As the survival is highly dependent on complete cytoreduction, the reported median survival of only 98 d is not surprising. Ideally, ascites caused by peritoneal cancer should be treated with complete cytoreduction and HIPEC. Unfortunately, Randle et al[8] found that complete macroscopic reduction can only be achieved in 15% of MA patients. The presence of MA is, therefore, a grave prognostic sign, as it is indicative of incomplete cytoreduction after surgery and HIPEC and worse overall survival. On the other hand, palliative HIPEC appeared to be highly successful in controlling MA, with 93% of patients being palliated even when complete cytoreduction was not possible. Both patient series suggest that HIPEC, without complete tumor debulking, can be a valid option for palliating MA, offering symptomatic relief with low complication rates and a short hospital stay[6,8].

In conclusion, this case report describes the successful palliation of MA by HIPEC in an elderly patient with severe symptoms. Although the prognosis of patients not suitable for curative treatment is dismal, alleviating the debilitating symptoms such as MA with HIPEC as a sole procedure should be considered.

A previously healthy 73-year-old man presented with abdominal distention, dyspnea, obstipation, dyschezia, and anorexia.

Upon physical examination, the patient showed dullness to percussion over the abdomen and shallow breathing.

Portal hypertension, peritonitis, portal vein occlusion, abdominal malignancy.

Computed tomography showed large amounts of ascites, a large rectosigmoidal mass with locoregional lymphadenopathy, and an omental cake, but no systemic metastases.

Biopsies taken during a colonoscopy and the pathologic investigation after a diagnostic laparoscopy confirmed the presence of mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet cell differentiation in the rectum and peritoneal deposits.

The patient was treated with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy without cytoreductive surgery.

Two case series previously described similar cases, with palliation of ascites in the majority of patients.

Cytoreductive surgery refers to the removal of visceral organs and peritoneal surfaces in order to treat peritoneally metastasized cancer.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy without cytoreductive surgery should be considered when managing symptomatic malignant ascites, even when the prognosis is dismal.

This is case report about hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in carcinomatosis can be reported because is a new tool for these patients.

P- Reviewer: Boin IFCF, Martinez-Costa OH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Cavazzoni E, Bugiantella W, Graziosi L, Franceschini MS, Donini A. Malignant ascites: pathophysiology and treatment. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sangisetty SL, Miner TJ. Malignant ascites: A review of prognostic factors, pathophysiology and therapeutic measures. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Jayne DG, Fook S, Loi C, Seow-Choen F. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1545-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 598] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ayantunde AA, Parsons SL. Pattern and prognostic factors in patients with malignant ascites: a retrospective study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:945-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Garofalo A, Valle M, Garcia J, Sugarbaker PH. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for palliation of debilitating malignant ascites. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:682-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Valle M, Van der Speeten K, Garofalo A. Laparoscopic hyperthermic intraperitoneal peroperative chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the management of refractory malignant ascites: A multi-institutional retrospective analysis in 52 patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:331-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Facchiano E, Scaringi S, Kianmanesh R, Sabate JM, Castel B, Flamant Y, Coffin B, Msika S. Laparoscopic hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for the treatment of malignant ascites secondary to unresectable peritoneal carcinomatosis from advanced gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:154-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Randle RW, Swett KR, Swords DS, Shen P, Stewart JH, Levine EA, Votanopoulos KI. Efficacy of cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of malignant ascites. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1474-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Klaver YL, Lemmens VE, Nienhuijs SW, Luyer MD, de Hingh IH. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: Incidence, prognosis and treatment options. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5489-5494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Esquivel J, Sticca R, Sugarbaker P, Levine E, Yan TD, Alexander R, Baratti D, Bartlett D, Barone R, Barrios P. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of peritoneal surface malignancies of colonic origin: a consensus statement. Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tamsma J. The pathogenesis of malignant ascites. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;134:109-118. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Tamsma JT, Keizer HJ, Meinders AE. Pathogenesis of malignant ascites: Starling’s law of capillary hemodynamics revisited. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1353-1357. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Pockros PJ, Esrason KT, Nguyen C, Duque J, Woods S. Mobilization of malignant ascites with diuretics is dependent on ascitic fluid characteristics. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1302-1306. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Becker G, Galandi D, Blum HE. Malignant ascites: systematic review and guideline for treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:589-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |