Published online Feb 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i2.21

Peer-review started: July 13, 2014

First decision: September 28, 2014

Revised: December 16, 2014

Accepted: January 9, 2015

Article in press: January 12, 201

Published online: February 27, 2015

Processing time: 213 Days and 20.8 Hours

A 72-year-old male underwent a laparoscopic low anterior resection for advanced rectal cancer. A diverting loop ileostomy was constructed due to an anastomotic leak five days postoperatively. Nine months later, colonoscopy performed through the stoma showed complete anastomotic obstruction. The mucosa of the proximal sigmoid colon was atrophic and whitish. Ten days after the colonoscopy, the patient presented in shock with abdominal pain. Abdominal computed tomography scan showed hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) and a dilated left colon. HPVG induced by obstructive colitis was diagnosed and a transverse colostomy performed emergently. His subsequent hospital course was unremarkable. Rectal anastomosis with diverting ileostomy is often performed in patients with low rectal cancers. In patients with anastomotic obstruction or severe stenosis, colonoscopy through diverting stoma should be avoided. Emergent operation to decompress the obstructed proximal colon is necessary in patients with a blind intestinal loop accompanied by HPVG.

Core tip: A rare case of hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is reported. Endoscopy through ileostomy leaded the formation of HPVG induced by obstructive colitis. The anastomosis of rectum was totally obstructed after rectum cancer operation. For nine months, the mucosa of ascending to sigmoid colon has changed atrophy for disuse. The patient’s condition improved after emergent operation of transverse colostomy. In patients with anastomotic obstruction or severe stenosis, colonoscopy through diverting stoma should be avoided.

- Citation: Sadatomo A, Koinuma K, Kanamaru R, Miyakura Y, Horie H, Lefor AT, Yasuda Y. Hepatic portal venous gas after endoscopy in a patient with anastomotic obstruction. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(2): 21-24

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i2/21.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i2.21

Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is a rare radiological sign associated with a wide range of abdominal abnormalities, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions. Factors leading to gas in the portal vein include mucosal damage caused by necrosis, bowel obstruction, and sepsis[1]. We report a case of HPVG following endoscopy performed through an ileostomy. The patient had severe anastomotic stenosis after low rectal cancer resection leading to a functional blind loop.

The patient is a 72-year-old man who underwent laparoscopic low anterior resection of rectal cancer nine months prior to presentation. Five days after the rectal resection with primary anastomosis, he underwent construction of a diverting ileostomy because of an anastomotic leak. The remainder of the hospital course was uneventful after the second operation. Histopathology showed a moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma with metastases to regional lymph nodes (T3N1M0). Adjuvant chemotherapy including tegafur-uracil (UFT) and leucovorin (UZEL) was administered for 6 mo.

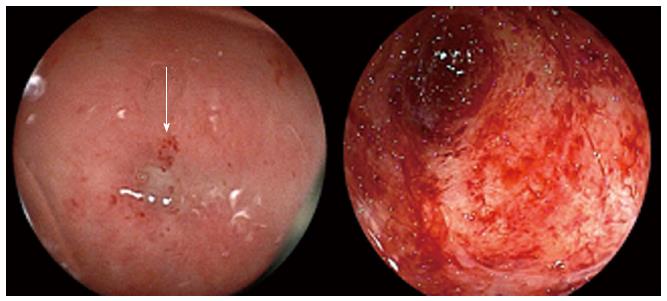

Colonoscopy performed per anus, eight months after resection, revealed severe stenosis at the rectal anastomosis. The pinhole lumen was covered by hard granulation tissue, and the endoscope could not pass through the hole. Following this, colonoscopy was performed through the ileostomy to examine the proximal colon, which confirmed that the anastomosis was completely obstructed and the proximal sigmoid colon mucosa was atrophic and whitish, consistent with chronic ischemic mucosal damage (Figure 1). The procedure was performed in 63 min. The patient complained of mild abdominal pain during the colonoscopy, but the pain improved soon after the examination. Six days after the colonoscopy, he visited his local physician with complaints of appetite loss and slight fever. He was diagnosed with acute enteritis based on laboratory data consistent with inflammation, and treated with oral antibiotics and an intestinal remedy.

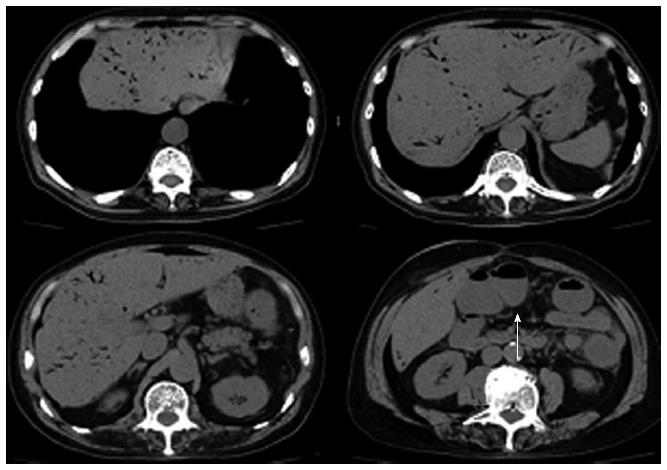

Ten days after the colonoscopy, he visited our hospital with a temperature of 40 °C, blood pressure of 83/49 mmHg, and pulse of 100/min. Physical examination showed mild tenderness in the lower part of the abdomen with no sign of peritonitis. Laboratory data showed a white blood cell count of 8900/mm3, C-reactive protein of 18.1 mg/dL, metabolic acidosis (PH = 7.374, anion gap of 12), and lactate dehydrogenase level of 1.1 mmol/L. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a large amount of HPVG. The transverse, descending and sigmoid colon were dilated with no free air or ascites (Figure 2).

We believe that HPVG was caused by obstructive colitis and septic shock following colonoscopy. An emergency laparotomy was performed, which revealed that the transverse colon was edematous and purple violet (Figure 3). A transverse colostomy was constructed. Stool culture revealed presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The postoperative course was uneventful and he was discharged on the seventh postoperative day. Four months later, ileostomy closure was performed.

HPVG was first described by Wolfe and Evens in infants[2] and has been associated with serious underlying diseases and a high mortality rate. HPVG has been reported to be associated with many conditions, such as necrotizing enterocolitis, bowel ischemia, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, graft-vs-host disease, bowel obstruction and iatrogenic complications[3]. HPVG has been associated with procedures including endoscopy[4,5], laparoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography[6], esophageal variceal band ligation and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement[7].

The diagnosis of HPVG is often made by abdominal CT scans with high sensitivity. It is possible to detect even a small amount of HPVG, leading to the early diagnosis of HPVG. HPVG is not necessarily an indication for surgery, and the prognosis depends on the underlying disease. Allaparthi et al[7] reported that the mortality rate of HPVG was 25% to 35%. HPVG associated with bowel necrosis and ischemia usually has a high risk of mortality, so urgent laparotomy is recommended for such patients. Patients with a more equivocal clinical presentation might be treated non-operatively with intensive monitoring[8]. In the present patient, clinical findings indicated that the patient was in septic shock and emergent operation was needed.

Factors that predispose to the development of HPVG include: (1) mucosal damage; (2) bowel distention; and (3) sepsis[1]. Two or three of these conditions often coexist in many patients. Mucosal damage may be secondary to necrotic bowel, ulcerative colitis, or ulcer disease. Intraluminal gas can enter the capillary veins easily through a damaged mucosal barrier. Intraluminal pressures are increased by enema or colonoscopy. An intra-abdominal abscess can contain gas-forming organisms leading to HPVG. In this patient, anastomotic leakage and subsequent stenosis was likely caused by impaired blood flow to the left colon. The colonic mucosa became atrophic because of the absence of fecal passage for over 9 mo. A closed loop from the ileocecal valve to the site of the anastomotic stricture became a functional blind loop and intraluminal pressures were increased by the colonoscopy. Although no bacterial blood cultures were obtained, we suggest that HPVG and sepsis were caused by bacterial translocation.

A rectal anastomosis with diverting ileostomy is performed in many patients with distal rectal cancer. In the case of anastomotic obstruction or severe stenosis, the colon proximal to the anastomosis may become a closed loop. Colonoscopy through the ileostomy should be avoided. Emergent surgery to decompress the obstructed bowel is necessary in such patients with a blind loop accompanied by HPVG.

Seventy-two years old man presented in shock with abdominal pain and high fevers ten days after colonoscopy through ileostomy.

Physical examination showed mild tenderness in the lower part of the abdomen with no sign of peritonitis.

Sepsis, gastrointestinal perforation.

White blood cells: 8900/mm3; C-reactive protein: 18.1 mg/dL; metabolic acidosis (PH 7.374, anion gap of 12).

Abdominal computerized tomography scan showed a large amount of hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) and dilated transverse, descending and sigmoid colon.

Emergent operation of transverse colostomy was done.

Some cases of iatrogenic HPVG were reported in English literature and they are named in author’s references. This is the first case report of HPVG induced by colonoscopy through ileostomy.

In the case of anastomotic obstruction or severe stenosis, colonoscopy through ileostomy should be avoided.

It is interesting.

P- Reviewer: Nayci A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, Benfield JR, Hechtman HB. Hepatic--portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wolfe JN, Evans WA. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; a roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955;74:486-488. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Abboud B, El Hachem J, Yazbeck T, Doumit C. Hepatic portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3585-3590. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kuo SM, Chang WK, Yu CY, Hsieh CB. Silent hepatic portal venous gas following upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E121-E122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rao S, Tkacz JN, Farraye FA. Portal venous gas after colonoscopy in two patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:316-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bobba RK, Arsura EL. Hepatic portal and mesenteric vein gas as a late complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in an elderly patient. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Allaparthi SB, Anand CP. Acute gastric dilatation: a transient cause of hepatic portal venous gas-case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:723160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nelson AL, Millington TM, Sahani D, Chung RT, Bauer C, Hertl M, Warshaw AL, Conrad C. Hepatic portal venous gas: the ABCs of management. Arch Surg. 2009;144:575-581; discussion 581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |