Published online Dec 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i12.384

Peer-review started: June 28, 2015

First decision: September 17, 2015

Revised: September 30, 2015

Accepted: November 10, 2015

Article in press: November 11, 2015

Published online: December 27, 2015

Processing time: 181 Days and 7 Hours

AIM: To compare long term outcomes of laparoscopic and open ventral hernia mesh repair with respect to recurrence, pain and satisfaction.

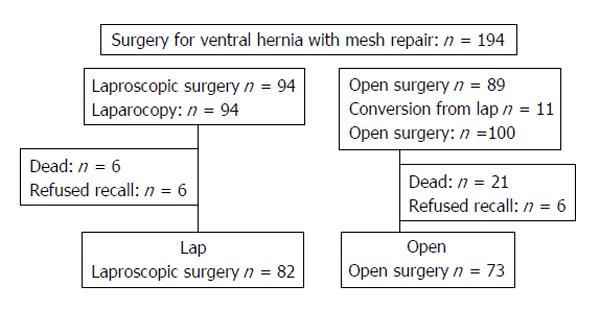

METHODS: We conducted a single-centre follow-up study of 194 consecutive patients after laparoscopic and open ventral hernia mesh repair between March 2000 and June 2010. Of these, 27 patients (13.9%) died and 12 (6.2%) failed to attend their follow-up appointment. One hundred and fifty-three (78.9%) patients attended for follow-up and two patients (1.0%) were interviewed by telephone. Of those who attended the follow-up appointment, 82 (52.9%) patients had received laparoscopic ventral hernia mesh repair (LVHR) while 73 (47.1%) patients had undergone open ventral hernia mesh repair (OVHR), including 11 conversions. The follow-up study included analyses of medical records, clinical interviews, examination of hernia recurrence and assessment of pain using a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) ruler anchored by word descriptors. Overall patient satisfaction was also determined. Patients with signs of recurrence were examined by magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scan.

RESULTS: Median time from hernia mesh repair to follow-up was 48 and 52 mo after LVHR and OVHR respectively. Overall recurrence rates were 17.1% after LVHR and 23.3% after OVHR. Recurrence after LVHR was associated with higher body mass index. Smoking was associated with recurrence after OVHR. Chronic pain (VAS > 30 mm) was reported by 23.5% in the laparoscopic cohort and by 27.8% in the open surgery cohort. Recurrence and late complications were predictors of chronic pain after LVHR. Smoking was associated with chronic pain after OVHR. Sixty point five percent were satisfied with the outcome after LVHR and 49.3% after OVHR. Predictors for satisfaction were absence of chronic pain and recurrence. Old age and short time to follow-up also predicted satisfaction after LVHR.

CONCLUSION: LVHR and OVHR give similar long term results for recurrence, pain and overall satisfaction. Chronic pain is frequent and is therefore important for explaining dissatisfaction.

Core tip: This is an observational and retrospective study of laparoscopic and open ventral mesh repair involving both incisional and non-incisional hernias. The principal outcome measures were recurrence, abdominal pain and satisfaction. Of the original cohort of 194 patients, 153 patients (78.9%) were examined individually with a mean follow-up period of 51 mo. Our results demonstrate an overall recurrence rate of 16.1% and we discuss the potential reasons. Excluding clinical recurrence, 13.7% suffered from chronic pain and 55.3% were satisfied with the outcome. Laparoscopic and open ventral mesh repair are comparable with respect to outcome measures.

- Citation: Langbach O, Bukholm I, Benth J&, Røkke O. Long term recurrence, pain and patient satisfaction after ventral hernia mesh repair. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(12): 384-393

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i12/384.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i12.384

Benefits and pitfalls[1] have been documented for both the mesh-reinforced open and laparoscopic approaches to incisional and ventral hernioplasty. Most papers suggest that laparoscopic ventral hernia mesh repair (LVHR) results in a shorter hospital stay, fewer wound complications and better cosmetic results compared to open ventral hernia mesh repair (OVHR)[2]. Favourable outcome of hernia surgery is often measured by the absence of recurrence and pain[3]. Chronic pain due to sensations of stiffness and foreign body reaction to the mesh, are adverse effects of mesh implantation[4,5]. Recurrence rates after LVHR and OVHR vary considerably and are related to surgical methods and skills, patient characteristics and length of follow-up[6]. The recurrence rate appears to reach peak incidence level after two years, with only small additional recurrences appearing later on[7].

The purpose of the present follow-up study was to compare laparoscopic and open mesh repair for incisional and non-incisional hernias in terms of complications, recurrence, pain and patient satisfaction with the outcome. As the study is of explorative character, no adjustments were made for multiple hypothesis testing.

We conducted a follow-up study of all patients undergoing mesh repair for incisional and non-incisional hernia at Akershus University Hospital, Norway between March 2000 and June 2010. Follow-up examinations were carried out by one surgeon and one study nurse. Data from medical records and clinical examinations were recorded. The recorded hernia operation is referred to as the index mesh repair.

We enrolled 194 consecutive patients, of whom 94 had been treated with laparoscopic mesh repair and 100 with open mesh repair including 11 conversions. Of these, 27 patients had died and 12 patients failed to attend their follow-up appointment without providing an explanation. There was no significant difference between the patient characteristics of eligible and non-eligible patients. One hundred and fifty-three patients attended their follow-up appointment and two patients were interviewed by telephone. Of the patients who attended their follow-up appointment, 82 (52.9%) had received a laparoscopic mesh repair while 73 (47.1%) patients had undergone open mesh repair, including 11 conversions from laparoscopic surgery due to intestinal injuries or technical problems (Figure 1). These 11 patients are included under open surgical procedures in tables and text, i.e., as per protocol. The patients were examined at various points after surgery as presented in Table 1. Median follow-up was 48 mo (9-88 mo) after LVHR and 52 mo (12-115 mo) after OVHR. Comorbidity was classified according to Charlson[8].

| Characteristics | Laparoscopic | Open | P value |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 56.5 ± 14.9 | 57.2 ± 11.6 | 0.76 |

| Gender: Male | 34 (41.5) | 34 (46.6) | 0.52 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 30.7 ± 6.2 | 29.7 ± 5.3 | 0.29 |

| ASA class | 0.64 | ||

| I | 13 (15.9) | 13 (17.8) | |

| II | 62 (75.6) | 55 (75.3) | |

| III | 7 (8.5) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Charlson index score | 0.41 | ||

| Score 0 | 25 (30.5) | 16 (21.9) | |

| Score 1 | 14 (17.1) | 19 (26.0) | |

| Score 2 | 16 (19.5) | 19 (26.0) | |

| Score 3 | 16 (19.5) | 12 (16.4) | |

| Score 4, 5, 6 | 11 (13.4) | 7 (9.6) | |

| Type of co-morbidity | 0.64 | ||

| Hypertension/congestive heart disease | 23 (28.0) | 19 (26.0) | |

| 3COPD | 16 (19.5) | 12 (16.4) | |

| Diabetes | 5 (6.1) | 5 (6.1) | |

| Neurological disease | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Multimorbid | 0 | 3 (4.1) | |

| Miscellaneous | 8 (9.8) | 10 (13.7) | |

| Smoking | 28 (34.1) | 26 (35.6) | 0.85 |

| Hernia type | 0.96 | ||

| Incisional | 66 (80.5) | 59 (80.8) | |

| Non-incisonal | 16 (19.5) | 14 (19.2) | |

| Recurrent hernia | 15 (18.3) | 13 (17.8) | 0.94 |

| Hernia area (cm2) ± SD | 57.5 ± 56.9 | 44.9 ± 52.9 | 0.17 |

| 1Incsional hernia | 0.41 | ||

| Small/medium < 70 cm2 | 44 (67.7) | 41 (74.5) | |

| Large ≥ 70 cm² | 21 (32.3) | 14 (25.5) | |

| 2Non-incisonal hernia | 0.003 | ||

| Small/medium < 13 cm2 | 6 (40.0) | 13 (92.9) | 0.06 |

| Large ≥ 13 cm2 | 9 (60.0) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Hernia location | 0.40 | ||

| Midline | 74(90) | 67 (92) | |

| Others | 8 (10) | 6 (8) | |

| Mesh size (cm2), mean ± SD | 235.1 ± 113.4 | 184.5 ± 124.3 | 0.03 |

| Follow up (mo), median, range | 48 (9-88) | 52 (12-115) | 0.006 |

Postoperative complications were classified according to Dindo et al[9]. Postoperative complications were recorded as minor (Clavien I + IIIa) or major (Clavien IIIb + IV).

Late complications (> 30 d after surgery) were recorded using medical records.

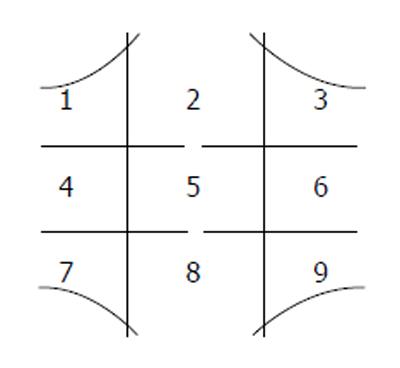

Pain was assessed by a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) ruler anchored by word descriptors at each end to calculate the patient’s impression of pain[10]. Chronic pain was defined as pain above 30 mm in the last 30 d[11]. During the examination, we asked about maximum abdominal wall pain in the last 30 d, and maximum abdominal wall pain associated with sedentary and moderate physical activities like climbing stairs, outdoor walking, gardening. The clinical examination focused on pain by palpating the abdominal wall in nine areas (Figure 2). Duration of surgery was divided into two categories by the median in each surgical group.

We adopted the classification by Muysoms et al[12] which distinguishes between non- incisional and incisional hernias and which classifies recurrent hernias of any origin as incisional. Hernia area was calculated by the formula: p/4 × A × B, where A and B are the two diagonals. Due to small numbers of patients in the small-sized non-incisional and incisional categories, we constructed a small and medium sized hernia group and a large sized hernia group in both categories. Incisional hernia size was categorised into ordinal variables as small/medium sized (< 70 cm2) and large sized hernias (≥ 70 cm2). Non-incisional hernia size was categorised into ordinal variables as small/medium sized (< 13 cm2) and large sized hernias (≥ 13 cm2) (Table 1). Hernia locations were defined by sectoral mapping of the abdominal wall[13].

The types of surgical approach and mesh selected were based on the surgeon’s preferences and experience. In laparoscopic mesh repair, the access to the abdominal cavity was established with open introduction of a 12 mm trocar. Capnoperitoneum was established with a pressure of 12 mmHg. Two or three additional abdominal trocars, 5 or 10 mm, were positioned on the surgeon’s side or on the contralateral side if appropriate. Adhesions were detached with scissors and occasionally with LigaSure® or ultracision. Fatty tissue on the inner abdominal wall was removed. The hernia sac was not routinely removed. The defect was measured. The mesh was introduced through the 12 mm trocar and placed over the defect with a minimum of 5 cm hernia overlap using tacks or transfacial non-absorbable sutures according to the surgeon’s preferences. The mesh did not necessarily cover the entire scar with a 5 cm overlap.

In open mesh repair, the incision was made over the hernia thus exposing the hernia content. The hernia sac was removed if possible. The peritoneum or posterior rectus sheet was dissected from the rectus muscle. The posterior sheet was not routinely closed with running absorbable sutures. The mesh was anchored in a retromuscular position with running non-resorbable transfacial sutures and seeking to achieve a 5 cm overlap. The anterior rectus sheet was not routinely closed. Neither intraperitoneal onlay mesh technique with Kugel patch nor mesh plug repair was applied. For small umbilical and epigastric hernias, the mesh was placed as described, but with minor modifications. Drains were used as per the surgeon’s preferences. Adhesions were graded according to Mazuji et al[14]. In the OVHR cohort, the adhesion score could not be established due to deficient reporting.

For the purpose of examining the association between intraperitoneal adhesions and complications, the grading was dichotomised into adhesions involving, or not involving, the intestine.

Clinical recurrence was determined at follow-up by physical examination and was defined as a detectable gap in the abdominal wall with or without bulging of viscera. Patients with signs of clinical recurrence were intentionally examined by magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scan. There were three false positive cases, two after OVHR and one after LVHR. Four patients with clinical recurrence, did not attend for radiology examination. Information received of ventral hernia mesh repair after the index operation was registered as recurrence. Overall recurrence was therefore defined as clinical recurrence, corrected for false positive cases together with information of ventral hernia mesh repair after the index operation.

The analysis was performed on a per protocol basis. Data in text and tables are given as mean ± SD, median (minimum-maximum) and frequency (percentage), as appropriate. For postoperative stay, we have chosen interquartile range instead of standard deviation due to some instances of extreme values[15]. Categorical variables were compared by the χ2-test and the Fisher exact test as appropriate. Comparison of continuous variables was performed using Student’s t-test. Non-parametric variables were handled and comparisons of median values were performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test and the Median test. Variables associated with postoperative complications, hernia recurrence, pain and overall satisfaction at the P < 0.1 level in bivariate analyses, were included in multivariate logistic regression models. The results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) with a 95%CI estimated by a multivariate model unless otherwise stated. All tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 0.05. The analyses were performed using the SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL United States).

Patient and hernia characteristics are presented in Table 1. The groups were similar with regard to age, gender, body mass index (BMI), comorbidity and smoking habits. Thirty-four point eight percent of the patients were smokers, 18.1% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma and 27.1% had hypertension and/or congestive heart disease. The observation time after open surgery was longer than after laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic surgery was more time-consuming compared to open hernia mesh repair (P = 0.002) (Table 2). There were 18 (22.0%) minor and seven (8.5%) major complications after LVHR and 22 (30.1%) minor and eight (11.0%) major complications after OVHR (P = 0.39) (Table 3). Six patients had two types of complications. Prolonged operative time was associated with an increased rate of minor complications after LVHR (P = 0.02), but not after OVHR (P = 0.28). Wound infection (P = 0.05, OR = 2.74, 95%CI: 0.99-7.65) and seroma (P = 0.01, OR = 3.65, 95%CI: 1.25-10.72) were more pronounced after OVHR. In the LVHR cohort, operative time > 108 min. was a predictor for postoperative complications in the crude model (OR = 3.96, 95%CI: 1.44-10.9). The presence of intraperitoneal adhesions involving the intestine (OR = 3.0, 95%CI: 1.1-8.2) or incisional hernias (OR = 8.4, 95%CI: 1.0-67.9) was a predictor for postoperative complications only in the crude model. In the OVHR cohort, large incisional hernias were not associated with postoperative complications in general (OR = 1.71, 95%CI: 0.46-6.32). In multivariate analysis only prolonged operative time was a predictor of postoperative complications (P < 0.03, OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 1.00-1.04) (Table 3). The need for postsurgical intervention was not different between the two groups (P = 0.58).

| Laparoscopic | Open | P value | |

| Operative time, min, mean ± SD | 117 ± 54 | 92 ± 44 | 0.002 |

| Emergency hernia operation | 0 | 12 (16.4) | |

| Preoperative antibiotics | 30 (36.6) | 33 (45.8) | 0.24 |

| Postoperative antibiotics | 12 (14.6) | 17 (23.3) | 0.17 |

| Postoperative stay, d, median (IQR) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-4) | 0.67 |

| No. of trocars, median (range) | 3 (3-6) | - | - |

| No. of tackers | 28 (10-70) | - | - |

| Mesh types | |||

| Polypropylene | 0 | 27 (38.0) | |

| Marlex | 0 | 7 (9.9) | |

| Bard composix | 20 (25.0) | 5 (7.0) | |

| Parietex composite | 39 (48.8) | 9 (12.7) | |

| Proceed | 7 (8.8) | 1 (1.4) | |

| TiMESH | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 6 (8.5) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 6 (8.5) |

| Laparoscopic | Open | P value | |

| Postoperative complications - grading | 0.39 | ||

| Minor (I- IIIa) | 18 (22.0) | 22 (30.1) | |

| Major (IIIb-IV) | 7 (8.5) | 8 (11.0) | |

| Postoperative complications - type | 0.17 | ||

| Wound infection | 6 (7.3) | 13 (17.8) | 0.05 |

| Seroma | 5 (6.1) | 14 (19.2) | 0.02 |

| Deep infection | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Pneumonia | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Unclassified infection | 3 (3.7) | 4 (5.5) | |

| Subcutaneous bleeding | 4 (4.9) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Substantial pain | 6 (7.3) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Others | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Intraoperative complications - type | 0.14 | ||

| Enterotomy | 0 | 4 (5.5) | |

| Colotomy | 1 (1.2) | 0 | |

| Late complications - type | 0.24 | ||

| Subileus/ileus | 3 (3.7) | 0 | |

| Deep infection | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Substantial pain | 4 (4.9) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Hematoma | 0 | 1 (1.4) | |

| Seroma | 4 (4.9) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Wound infection | 1 (1.2) | 4 (5.5) | |

| Others | - | 2 (2.7) |

We discriminated between clinical recurrence and overall recurrence at follow-up. Ten patients had surgery for recurrence in the follow-up period, six of these had no recurrence at follow-up. The frequency of recurrence judged clinically, was 10 (12.2%) after LVHR and 15 (20.5%) after OVHR. Information received of hernia surgery for recurrence after the index mesh repair, confirmed an overall recurrence rate of 14 (17.1%) after LVHR and 17 (23.3%) after OVHR (P = 0.33) (Table 4). In univariate analysis, hernia size, BMI, numbers of trocars and length of postoperative stay were associated with recurrence (Table 5). Variables thought of as confounders, namely gender, age, BMI and COPD, were adjusted for in multivariate analysis. There was no difference between incisional and non-incisional hernias with respect to recurrence. In the multivariate model, BMI, number of trocars and length of postoperative stay were independent predictors of recurrence (Table 6). In the OVHR cohort, univariate analysis showed that smoking, postoperative complications in general and length of postoperative stay were factors associated with recurrence (Table 7). In multivariate analysis, only smoking (OR = 4.18, 95%CI: 1.22-14.38) was an independent predictor of recurrence in the crude and adjusted model (Table 8). Gender, BMI and COPD did not change the associations. Wound infection and seroma were not factors associated with recurrence.

| Yes | No | P value | |

| Gender male/female | 7/7 | 27/41 | 0.48 |

| Age at hernia surgery; yr; mean ± SD | 52 ± 14 | 57 ± 15 | 0.24 |

| Period of follow-up, mo ± SD | 46 ± 15 | 46 ± 17 | 0.94 |

| Charlson index | 0.79 | ||

| 0 | 6 (24.0) | 19 (76.0) | |

| 1 | 2 (14.3) | 12 (85.7) | |

| 2 | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | |

| 3 | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.3) | |

| 4, 5, 6 | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | |

| COPD | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.3) | 0.84 |

| Smoking | 5 (17.9) | 23 (82.1) | 0.89 |

| BMI (kg/m2); mean ± SD | 34 ± 6 | 30 ± 6.0 | 0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2); (%) 18.5-24.9 | 1 (8.3) | 11 (92.7) | 0.38 |

| BMI (kg/m2); (%) 25.0-29.9 | 3 (12.0) | 22 (88.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2); (%) 30.0-39.9 | 10 (22.2) | 35 (77.8) | |

| Hernia type | 0.59 | ||

| Incisional | 12 (18.2) | 54 (81.8) | |

| Non-incisional | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | |

| Recurrent hernia | 2 (13.3) | 13 (86.7) | 0.67 |

| Hernia area, cm2, mean ± SD | 80 ± 58 | 53 ± 56 | 0.11 |

| Hernia area, both types < 58 cm2 | 5 (9.8) | 46 (90.2) | 0.04 |

| Hernia area, both types ≥ 58 cm2 | 8 (27.6) | 21 (72.4) | |

| Incisonal hernia area < 70 cm2, n1 | 6 (13.6) | 38 (86.4) | 0.15 |

| Incisonal hernia area ≥ 70 cm2, n | 6 (28.6) | 15 (71.4) | |

| Non-incisonal hernia area < 13 cm2, n | 0 | 6 | 0.40 |

| Non-incisonal hernia area ≥ 13 cm2, n | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | |

| No. of trocars, median, (range) | 4 (3-6) | 3 (3-5) | < 0.001 |

| Operative time, min, mean ± SD | 142 ± 63 | 112 ± 51 | 0.07 |

| Postoperative stay, d, mean ± SD | 4 ± 4 | 2 ± 1 | 0.001 |

| Preop antibiotics | 8 (26.7) | 22 (73.3) | 0.08 |

| Surgeons experience | 0.69 | ||

| Less experient | 7 (15.6) | 38 (84.4) | |

| Experient | 7 (18.9) | 30 (81.1) | |

| Mesh | 0.47 | ||

| Goretex | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | |

| Parietex | 7 (17.5) | 33 (82.5) | |

| Bard | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | |

| Other | 0 | 9 | |

| Postoperative complications | 5 (20.0) | 20 (80.0) | 0.64 |

| Postoperative antibiotics | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | 0.43 |

| Late complications | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) | 0.86 |

| Hernia belt | 11 (22.0) | 39 (78.0) | 0.14 |

| Yes | No | P value | |

| Gender male/female | 9/8 | 25/31 | 0.55 |

| Age at hernia surgery, yr, mean ± SD | 57 ± 11 | 57 ± 12 | 1.0 |

| Period of follow-up, mo ± SD | 56 ± 26 | 57 ± 30 | 0.91 |

| Charlson index | 0.86 | ||

| 0 | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.3) | |

| 1 | 6 (31.6) | 13 (68.4) | |

| 2 | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | |

| 3 | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | |

| 4, 5, 6 | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) | |

| COPD | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | 0.88 |

| Smoking | 10 (38.5) | 16 (61.5) | 0.02 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 31 ± 6.0 | 29 ± 5.1 | 0.25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (%)18.5-24.9 | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.80 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (%) 25.0-29.9 | 5 (19.2) | 21 (80.8) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (%) 30.0-39.9 | 10 (27.8) | 26 (72.2) | |

| Emergency operation | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | 1.0 |

| Hernia type | 1.0 | ||

| Incisional | 14 (23.7) | 45 (76.3) | |

| Non-incisional | 3 (21.4) | 11 (78.6) | |

| Recurrent hernia | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) | 0.72 |

| Hernia area, cm2, mean ± SD | 39 ± 56 | 47 ± 52 | 0.60 |

| 1Incisonal hernia area < 70 cm2 | 11 (26.8) | 30 (73.2) | 0.48 |

| Incisonal hernia area ≥ 70 cm2 | 2 (14.3) | 12 (85.7) | |

| Non-incisonal hernia area < 13 cm2 | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) | 0.21 |

| Non-incisonal hernia area ≥ 13 cm2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Mesh area, cm2, mean ± SD | 186 ± 112 | 184 ± 131 | 0.97 |

| Operative time, min, mean ± SD | 97 ± 65 | 90 ± 36 | 0.56 |

| Preop antibiotics | 8 (24.2) | 25 (75.8) | 0.70 |

| Surgeons experience | 0.98 | ||

| Less experient | 6 (23.1) | 20 (76.9) | |

| Modest experient | 11 (23.4) | 36 (76.6) | |

| Mesh | 0.63 | ||

| Goretex | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) | |

| Polypropylene | 5 (19.2) | 21 (80.8) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 6 | |

| Other | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | |

| Postoperative complications | 11 (36.7) | 19 (63.3) | 0.02 |

| Seroma | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) | 0.22 |

| Wound infection | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | 0.48 |

| Postoperative antibiotics | 7 (52.9) | 10 (47.1) | 0.05 |

| Late complications | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) | 0.22 |

| Postoperative stay, d, mean ± SD | 8 ± 19 | 2 ± 2 | 0.02 |

| Hernia belt | 5 (15.6) | 27 (84.4) | 0.54 |

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Smoking | 4.18 (1.22; 14.38) | 0.002 |

| Postoperative complications | 2.36 (0.49; 11.45) | 0.287 |

| Postoperative antibiotics | 1.36 (0.25; 7.43) | 0.722 |

| Postoperative stay | 1.18 (0.89; 1.57) | 0.254 |

There was no difference in reported pain or pain on palpation between the two surgical groups, calculated with the adjustment factors of clinical recurrence, age, BMI, gender, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Table 9). Clinical recurrence was associated with maximum reported pain in both surgical cohorts, but only after LVHR during sedentary (OR = 5.78, 95%CI: 1.11-30.05) and physical activity (OR = 14.22, 95%CI: 1.75-116.05). Adjusting for clinical recurrence, BMI, age and COPD, it was found that after LVHR, female gender was associated with maximum reported pain (OR = 7.37, 95%CI: 1.36-39.85). In addition, young age and low BMI were factors associated with pain during sedentary and physical activity (Table 10). In the OVHR cohort, there was no association between pain and gender, age and BMI, but with hernia recurrence (OR = 18.04, 95%CI: 1.80-181.09) (P < 0.05). Among subjects without clinical recurrence, 13 patients (18.3%) vs eight patients (15.4%) experienced chronic pain in the LVHR and OVHR cohorts respectively (P = 0.53). In multivariate regression analysis, clinical recurrence (OR = 11.67, 95%CI: 2.00-68.24) and history of late complications (OR = 5.47, 95%CI: 1.11-27.09) were factors associated with chronic pain in the LVHR group (Table 11). Together with female gender, age, COPD and smoking (adjustment factors), these covariates could explain 41% of the variance on the dependent variable.

| Laparoscopic n = 81 | Open n = 72 | OR1 (95%CI) | P value | |

| Maximum pain reported, mean ± SD | 16.7 (20.8) | 18.6 (20.8) | 1.40 (0.42-4.68) | 0.58 |

| Maximum pain on palpation, mean ± SD | 12.9 (20.2) | 12.1 (20.2) | 0.78 (0.26-2.32) | 0.66 |

| Pain on average, mean ± SD | 3.3 (10.3) | 2.4 (6.4) | 0.85 (0.49-1.47) | 0.56 |

| Pain during sedentary activities, mean ± SD | 6.5 (17.9) | 4.0 (15.4) | 0.61 (0.31-1.22) | 0.16 |

| Pain during work activities, mean ± SD | 9.8 (17.9) | 7.7 (15.4) | 0.68 (0.24-1.89) | 0.46 |

| Maximum pain | Average pain | Pain, sedentary | Pain, work | |

| OR (95%CI)2 | OR (95%CI)3 | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| 1 | LVHR | LVHR | LVHR | |

| Gender | 7.372 (1.4-39.9) | NA | NA | NA |

| Age | 19.773 (3.4-115.5) | NA | 3.713 (1.1-12.6) | 7.043 (1.5-33.0) |

| BMI | 14.564 (2.4-90.0) | 5.034 (1.4-18.3) | 7.244 (1.5-35.1) | 9.734 (1.3-73.0) |

| COPD | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Clinical recurrence excluded | ||||

| LVHR | 32.04 (2.82-363.22) | NA | 5.78 (1.11-30.05) | 14.22 (1.75-116.05) |

| OVHR | 18.04 (1.80-181.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Clinical recurrence | 11.67 (2.00-68.24) | 0.006 |

| Late complications | 5.47 (1.1-27.09) | 0.037 |

| Gender (referes female) | 0.42 (0.10-1.98) | 0.274 |

| Age > 60 yr | 0.23 (0.03-1.51) | 0.125 |

| COPD | 2.39 (0.52-11.10) | 0.265 |

| Smoking | 1.38 (0.37-5.11) | 0.629 |

In the OVHR cohort smoking was associated with chronic pain in the crude model (OR = 3.85, 95%CI: 1.24-11.99) but not in the adjusted model (OR = 3.81, 95%CI: 0.95-15.34) (Table 12). In the whole model, clinical recurrence, female gender, postoperative complications, late complications and admission time, could only explain 30.7% of the variance on the dependent variable.

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Clinical recurrence | 1.20 (0.24-6.06) | 0.828 |

| Smoking (crude model) | 3.86 (1.24-12.00) | 0.020 |

| Smoking (adjusted model) | 3.81 (0.95-15.33) | 0.060 |

| Hernia size > 70 cm2 | 0.84 (0.13-5.53) | 0.852 |

| Gender (ref female) | 0.30 (0.07-1.35) | 0.116 |

| Postoperative complications | 3.59 (0.76-16.88) | 0.106 |

| Late complications | 1.16 (0.20-6.87) | 0.869 |

| Postoperative stay | 1.08 (0.75-1.57) | 0.668 |

Satisfaction among patients after hernia surgery was established by “yes/no” responses to whether they experienced abdominal wall pain or discomfort. Of 152 patients reporting their symptoms, 49 patients (60.5%) were satisfied with LVHR and 35 patients (49.3%) were satisfied with OVHR (P = 0.17). Absence of chronic pain (OR = 7.4, 95%CI: 1.43-38.46), age over 60 years (OR = 7.16, 95%CI: 1.37-37.42) at hernia surgery and shorter time to follow-up (OR = 1.83, 95%CI: 1.11-3.05) was associated with satisfaction after LVHR (Table 13). Absence of clinical recurrence was associated with satisfaction only in the crude model (OR = 7.81, 95%CI: 1.54-40.00). These covariates, including female gender and late complications, could explain 55.7% of the variance on the dependent variable. In the OVHR cohort, no clinical recurrence (OR = 20.00, 95%CI: 2.15-200.00) and absence of chronic pain (OR = 5.56, 95%CI: 1.24-25.00) were associated with satisfaction (Table 14). Covariates, including admission time and late complications, could explain 45.7% of the variance on the dependent variable.

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Chronic pain1 | 0.14 (0.03-0.70) | 0.017 |

| Age > 60 yr | 7.16 (1.37-37.42) | 0.020 |

| Gender (ref female) | 2.69 (0.72-10.05) | 0.142 |

| Time to follow up | 0.55 (0.33-0.90) | 0.019 |

| Clinical recurrence (crude model) | 0.13 (0.03-0.65) | 0.013 |

| Clinical recurrence (adjusted model) | 0.13 (0.02-1.11) | 0.062 |

| Late complications | 0.39 (0.07-2.23) | 0.289 |

In the present study, patients who had undergone open mesh repair experienced a higher frequency of wound complications compared to the laparoscopic group, thus supporting previous studies[2]. The higher frequency of enterotomy in the open surgery group is due to perioperative bowel injuries during laparoscopy, and conversion to open surgery. There were, however, no differences between the two groups witch regard to overall postoperative complication rates and postoperative stay, which is somewhat surprising.

In the present study, the overall recurrence rates were 17.1% after laparoscopic mesh repair and 23.3% after open mesh repair (P = 0.33). The median time from hernia surgery to follow-up was only four months longer in the open mesh repair group and would probably have no impact on recurrence. Even though our recurrence rates were high after both LVHR and OVHR, the mean follow-up time was longer than in many other studies. The great variation of follow-up time among different studies could affect recurrence rates. There are also other factors to consider: Our study involved mandatory examination of all patients. Patients who report no symptoms of recurrence in mailed questionnaires can easily be misdiagnosed. Finally, we need to consider that relatively small numbers of patients are followed-up in some of the previously conducted studies[16].

A Cochrane review reported a recurrence rate of only 4.2% after open hernia mesh repair (15/326), but the follow-up time was relatively short (< 2 years in four of nine studies included)[1]. The review included both incisional and ventral hernia. Lauscher et al[17] reported a recurrence rate of 13.3% in 90 patients 18 mo after open incisional hernia mesh repair.

Comparing laparoscopic (n = 119) and open (n = 106) hernia mesh repair, a retrospective study from the Cleveland clinic, showed a 5-year recurrence rate of 28% in the open mesh repair group and 29% in the laparoscopic mesh repair group. There were both incisional and non-incisional hernias included[18]. Eker et al[16] reported recurrence rates of 14% and 18% after open and laparoscopic incisonal hernia repairs. They conducted a large randomized controlled multicentre trial with a mean follow-up period of 35 mo. Of 194 patients in our study, 146 (75%) completed the follow-up. There are very few studies with a follow-up longer than 5 years. It is suggested that the threshold for recurrence is 5 years after ventral hernia surgery[18].

The mechanisms underlying recurrence could be due to infection, lateral detachment of the mesh, inadequate mesh fixation, inadequate overlap and mesh shrinkage[19]. Schoenmacker reported a 7.5% shrinkage rate and no difference in recurrence after comparing one group with double crown of tacks to another group with tacks and sutures[20]. Another retrospective study reported a shrinkage rate of 6.7% after LVHR and the use of ePTFE (Dualmesh) with double crown fixation and sutures evaluated by CT scans[21]. In our laparoscopic group, there was no association between mesh/hernia area ratio and overall recurrence (P = 0.45). Smoking was a predictor for overall recurrence after OVHR both in the crude and the adjusted model. There was no association between smoking and overall recurrence after LVHR. The finding that smoking is a risk factor for developing incisional hernia after laparotomy is in accordance with Sorensen and others[22]. Smoking has also been found to be a risk factor for recurrence, after both open suture repair[23] and laparoscopic hernia mesh repair[24].

The rate of seroma was higher after OVHR, but was not associated with overall recurrence. For laparoscopic mesh repairs, increasing the number of trocars was associated with overall recurrence. Large hernia areas (> 58 cm2) had more recurrences (P = 0.095), an observation which agrees with those of others[16]. After OVHR, postoperative complications in general were associated with overall recurrence only in the crude model.

We did not find any difference in abdominal pain between the cohorts. Clinical recurrence was a causative and predictive factor for pain after both LVHR and OVHR. Other factors also modulate the notion of pain, but could only be confirmed after LVHR. In our study it was found, that after adjusting for recurrence, female gender, low BMI and young age were all factors associated with higher levels of reported pain. This gender difference across different diseases, has recently been reported[25].

The use of tacks vs sutures or the number of tacks used, had no implication on abdominal wall pain in the laparoscopic group. Muysoms et al[26] reported more patients with abdominal wall pain (VAS > 10 mm) after sutures and tacks (31.4%) compared to tacks in a double circle shape (8.3%). This was registered three months after LVHR. Wassenaar et al[27] found no correlation between number of tacks and pain three months after LVHR.

The terms mild, moderate and severe pain have been discussed in several publications[10,19,28]. The cut-off value for differentiating between moderate and severe pain can differ among studies, but seems to be fairly consistent, particularly on the intercept between mild and moderate pain. This is also the case for the numerical rating scale[10]. Liang et al[30] looked at the relationship between chronic pain and other clinical characteristics in 122 patients after LVHR and found that 17.2% of the patients experienced chronic abdominal pain 24 mo after hernia surgery. He assessed patient experience on a 10-point numerical scale. Unfortunately, he did not specify the cut-off value on the numerical rating scale; only the patients’ own rating. Eriksen et al[31] reported that less than 10% had VAS pain scores > 5 six months after LVHR. Setting the cut-off value at 10 mm on the VAS, we found that 39.5% reported pain after LVHR and 43.1% after OVHR. The difference between our results and those reported by others, is their lack of precise criteria for the definition of chronic pain. Furthermore, there is great variation in the time from operation to clinical follow-up in many studies. Excluding recurrence, 13 patients (18.3%) and eight patients (15.4%) reported chronic pain after LVHR and OVHR respectively.

Percent of 60.5 the patients were satisfied after LVHR and 49.3% after OVHR. Excluding clinical recurrence, 66.2% and 60.7% were satisfied after laparoscopic and open hernia surgery respectively, there being no other significant difference. Factors other than recurrence will therefore have an influence on patient satisfaction. The equality of long term satisfaction rates between LVHR and OVHR has been confirmed by others[32]. Liang et al[30] used a 10-point numerical scale to assess satisfaction after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. He set the cut-off value for satisfaction to ≥ 7. In his study, 74.5% of patients were satisfied with the outcome. Chronic pain and recurrence were associated with reduced overall satisfaction.

In our study, absence of chronic pain was the most important factor for satisfaction after LVHR. Old age at hernia surgery also predicted satisfaction, while clinical recurrence was predictive only in the crude model. Longer follow-up was associated with discontent in our study and could be due to increased rate of recurrence, though this is not proven.

Chronic pain and clinical recurrence was associated with discontent after OVHR.

Eriksen et al[31] also found that pain was associated with dissatisfaction after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (P < 0.001). They had however no recurrences. Gronnier et al[11] found that almost 83% were satisfied more than 2 years after open hernia mesh repair. A recurrence rate of 6.1% at the repair site could explain the higher rate of satisfaction compared to our results (20.5% recurrence rate/49.3% satisfaction rate).

There are obvious limitations to our study. The study population is relatively small and our retrospective analysis on the basis of medical records and the heterogeneity of ventral hernia type and location, calls for careful interpretation of results. The study does however also benefit from some clear advantages: Nearly 79% of the original cohort attended for examination at follow-up. Also, the study was conducted at a single institution with an established examination protocol, and interviews were conducted by a single experienced doctor.

In conclusion, there was no difference in long term recurrence, pain and overall patient satisfaction after open and laparoscopic mesh repair. We demonstrated a relatively high frequency of hernia recurrences. We could also demonstrate that the two techniques had different predisposing factors for recurrence. High BMI was the most important cause of recurrence after LVHR, while smoking was the most important factor after OVHR. Hernia recurrence is associated with more pain, but pain without recurrence is also quite frequent. The absence of chronic pain is the most important factor for patient satisfaction after ventral hernia surgery.

No precise data on the incidence and prevalence of non-incisional and incisional hernias are available, but the reported incidence rates for incisional hernia after laparotomy are between 9% and 20%; this represents one of the most common complications after abdominal surgery. Non-incisional and incisional hernias are treated with surgery for cosmetic reasons, but mainly to relieve pain and discomfort, prevent respiratory or skin problems and resolve incarceration or strangulation. The surgical and patient reported outcomes vary according to surgical skills and method, type and size of hernia, type of mesh and the length of follow-up. Patient characteristics are also important.

The ultimate goal in ventral hernia surgery is to improve and restore the patients’ quality of life. This is achievable with emphasis on the patients’ reported outcomes. Surgical approach, mesh considerations and surgical outcome will benefit from well designed studies with sufficiently long follow-up and examination of all participants.

This is the first report from Norway that compares the outcome of laparoscopic and open ventral hernia mesh repair. It is a retrospective observational study with a mixture of non-incisional and incisional hernias, but the authors were able to examine nearly 80% of the original cohort and 92% of those that were still alive at long-term follow up.

The results presented in this study confirm that laparoscopic and open mesh repair involve complications and pitfalls that put significant demands on surgical skills. The recurrence rate could most likely be lowered in the hands of experts. The selection of patients for open or laparoscopic repair could also benefit from surgical skills of a high standard and better knowledge of the many aspects of hernia disease.

The term ventral hernia often refers to a primary hernia which has not been caused by earlier surgery. The authors use the term to refer to both incisional and non-incisional hernias located in the anterior abdominal wall.

This single-centre study has undergone peer-review by colleagues with a science background both at preparation stage and during the follow-up examinations. The results were discussed and revised internally throughout this process.

P- Reviewer: Dedemadi G, Liu H, Milone M, OtowaY S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Sauerland S, Walgenbach M, Habermalz B, Seiler CM, Miserez M. Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD007781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Müller-Riemenschneider F, Roll S, Friedrich M, Zieren J, Reinhold T, von der Schulenburg JM, Greiner W, Willich SN. Medical effectiveness and safety of conventional compared to laparoscopic incisional hernia repair: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2127-2136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bringman S, Conze J, Cuccurullo D, Deprest J, Junge K, Klosterhalfen B, Parra-Davila E, Ramshaw B, Schumpelick V. Hernia repair: the search for ideal meshes. Hernia. 2010;14:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Klosterhalfen B, Junge K, Klinge U. The lightweight and large porous mesh concept for hernia repair. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2005;2:103-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Klinge U, Conze J, Limberg W, Brücker C, Ottinger AP, Schumpelick V. [Pathophysiology of the abdominal wall]. Chirurg. 1996;67:229-233. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Itani KM, Hur K, Kim LT, Anthony T, Berger DH, Reda D, Neumayer L. Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair with mesh for the treatment of ventral incisional hernia: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2010;145:322-328; discussion 328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Singhal V, Szeto P, VanderMeer TJ, Cagir B. Ventral hernia repair: outcomes change with long-term follow-up. JSLS. 2012;16:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Jensen MP, Chen C, Brugger AM. Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. J Pain. 2003;4:407-414. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Gronnier C, Wattier JM, Favre H, Piessen G, Mariette C. Risk factors for chronic pain after open ventral hernia repair by underlay mesh placement. World J Surg. 2012;36:1548-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Muysoms FE, Miserez M, Berrevoet F, Campanelli G, Champault GG, Chelala E, Dietz UA, Eker HH, El Nakadi I, Hauters P. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13:407-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lang RA, Buhmann S, Hopman A, Steitz HO, Lienemann A, Reiser MF, Jauch KW, Hüttl TP. Cine-MRI detection of intraabdominal adhesions: correlation with intraoperative findings in 89 consecutive cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2455-2461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mazuji MK, Kalambaheti K, Pawar B. Prevention of adhesions with polyvinylpyrrolidone. preliminary report. Arch Surg. 1964;89:1011-1015. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Manikandan S. Measures of dispersion. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2:315-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Eker HH, Hansson BM, Buunen M, Janssen IM, Pierik RE, Hop WC, Bonjer HJ, Jeekel J, Lange JF. Laparoscopic vs. open incisional hernia repair: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:259-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lauscher JC, Loh JC, Rieck S, Buhr HJ, Ritz JP. Long-term follow-up after incisional hernia repair: are there only benefits for symptomatic patients? Hernia. 2013;17:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ballem N, Parikh R, Berber E, Siperstein A. Laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia repairs: 5 year recurrence rates. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1935-1940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bittner R, Bingener-Casey J, Dietz U, Fabian M, Ferzli GS, Fortelny RH, Köckerling F, Kukleta J, LeBlanc K, Lomanto D. Guidelines for laparoscopic treatment of ventral and incisional abdominal wall hernias (International Endohernia Society [IEHS])-Part 2. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:353-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schoenmaeckers EJ, van der Valk SB, van den Hout HW, Raymakers JF, Rakic S. Computed tomographic measurements of mesh shrinkage after laparoscopic ventral incisional hernia repair with an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene mesh. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1620-1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Carter PR, LeBlanc KA, Hausmann MG, Whitaker JM, Rhynes VK, Kleinpeter KP, Allain BW. Does expanded polytetrafluoroethylene mesh really shrink after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair? Hernia. 2012;16:321-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sørensen LT, Hemmingsen UB, Kirkeby LT, Kallehave F, Jørgensen LN. Smoking is a risk factor for incisional hernia. Arch Surg. 2005;140:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Clark JL. Ventral incisional hernia recurrence. J Surg Res. 2001;99:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bencini L, Sanchez LJ, Bernini M, Miranda E, Farsi M, Boffi B, Moretti R. Predictors of recurrence after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ruau D, Liu LY, Clark JD, Angst MS, Butte AJ. Sex differences in reported pain across 11,000 patients captured in electronic medical records. J Pain. 2012;13:228-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Muysoms F, Vander Mijnsbrugge G, Pletinckx P, Boldo E, Jacobs I, Michiels M, Ceulemans R. Randomized clinical trial of mesh fixation with “double crown” versus “sutures and tackers” in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2013;17:603-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Wassenaar E, Schoenmaeckers E, Raymakers J, van der Palen J, Rakic S. Mesh-fixation method and pain and quality of life after laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair: a randomized trial of three fixation techniques. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1296-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61:277-284. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Hoffman DL, Sadosky A, Dukes EM, Alvir J. How do changes in pain severity levels correspond to changes in health status and function in patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy? Pain. 2010;149:194-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liang MK, Clapp M, Li LT, Berger RL, Hicks SC, Awad S. Patient Satisfaction, chronic pain, and functional status following laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. World J Surg. 2013;37:530-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Eriksen JR, Poornoroozy P, Jørgensen LN, Jacobsen B, Friis-Andersen HU, Rosenberg J. Pain, quality of life and recovery after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2009;13:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Misra MC, Bansal VK, Kulkarni MP, Pawar DK. Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair of incisional and primary ventral hernia: results of a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1839-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |