Published online Nov 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i11.335

Peer-review started: March 15, 2015

First decision: April 13, 2015

Revised: May 31, 2015

Accepted: July 15, 2015

Article in press: August 25, 2015

Published online: November 27, 2015

Processing time: 94 Days and 0.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate the simplicity, reliability, and safety of the application of single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis in pancreaticoduodenectomy.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis was performed on the data of patients who received pancreaticoduodenectomy completed by the same surgical group between January 2011 and April 2014 in the General Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army. In total, 51 cases received single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and 51 cases received double-layer pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. The diagnoses of pancreatic fistula and clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy were judged strictly by the International Study Group on pancreatic fistula definition. The preoperative and intraoperative data of these two groups were compared. χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze the incidences of pancreatic fistula, peritoneal catheterization, abdominal infection and overall complications between the single-layer anastomosis group and double-layer anastomosis group. Rank sum test were used to analyze the difference in operation time, pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time, postoperative hospitalization time, total hospitalization time and hospitalization expenses between the single-layer anastomosis group and double-layer anastomosis group.

RESULTS: Patients with grade A pancreatic fistula accounted for 15.69% (8/51) vs 15.69% (8/51) (P = 1.0000), and patients with grades B and C pancreatic fistula accounted for 9.80% (5/51) vs 52.94% (27/51) (P = 0.0000) in the single-layer and double-layer anastomosis groups. Although there was no significant difference in the percentage of patients with grade A pancreatic fistula, there was a significant difference in the percentage of patients with grades B and C pancreatic fistula between the two groups. The operation time (220.059 ± 60.602 min vs 379.412 ± 90.761 min, P = 0.000), pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time (17.922 ± 5.145 min vs 31.333 ± 7.776 min, P = 0.000), postoperative hospitalization time (18.588 ± 5.285 d vs 26.373 ± 15.815 d, P = 0.003), total hospitalization time (25.627 ± 6.551 d vs 33.706 ± 15.899 d, P = 0.002), hospitalization expenses (116787.667 ± 31900.927 yuan vs 162788.608 ± 129732.500 yuan, P = 0.001), as well as the incidences of pancreatic fistula [13/51 (25.49%) vs 35/51 (68.63%), P = 0.0000], peritoneal catheterization [0/51 (0%) vs 6/51 (11.76%), P = 0.0354], abdominal infection [1/51 (1.96%) vs 11/51 (21.57%), P = 0.0021], and overall complications [21/51 (41.18%) vs 37/51 (72.55%), P = 0.0014] in the single-layer anastomosis group were all lower than those in the double-layer anastomosis group.

CONCLUSION: Single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis appears to be a simple, reliable, and safe method. Use of this method could reduce the postoperative incidence of complications.

Core tip: Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a complex surgical procedure with a high perioperative complication rate and a high mortality rate, therefore, pancreaticoduodenectomy is considered a dangerous surgery. Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis plays an important role in pancreaticoduodenectomy; its success determines the success of the surgery. In our study, there was a significant difference in the percentage of patients with grades B and C pancreatic fistula between the two groups. Single-layer anastomosis was better than double-layer anastomosis when the pancreatic texture was soft. The use of this method could reduce the rates of postoperative pancreatic fistula, abdominal infection and peritoneal catheterization.

- Citation: Hu BY, Leng JJ, Wan T, Zhang WZ. Application of single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis in pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(11): 335-344

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i11/335.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i11.335

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is the primary surgical method for the treatment of pancreatic head tumors, distal bile duct tumors, ampullary tumors, duodenal tumors, and duodenal papilla tumors. However, because it is a complex surgical procedure with a high perioperative complication rate and a high mortality rate, pancreaticoduodenectomy is considered a dangerous surgery. In the literature, the reported incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula associated with this procedure differs due to the use of different definitions of pancreatic fistula; overall, the incidence ranges from 10% to greater than 30%[1-4]. Pancreatic fistula was associated with delayed gastric emptying, intra-abdominal abscess, local infection at the incision site, sepsis, and blood loss after pancreaticoduodenectomy[5-8]. Although the complication and mortality rates associated with pancreatic fistula have decreased due to improvements in perioperative management, surgical techniques and timely and proper management of postoperative complications[5,9,10], the incidence of postoperative complications during the perioperative period is still 30%-60%[11-15].

Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis plays an important role in pancreaticoduodenectomy; its success determines the success of the surgery. Currently, pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is considered a weak link in pancreaticoduodenectomy[16,17]. Although several advocated methods of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis are considered to be able to reduce the occurrence of pancreatic fistula, the question of which pancreaticojejunal anastomosis method is best is still debatable[18-25]. This study describes a new, safe, simple, easy-to-suture, and reliable method for pancreaticojejunal anastomosis.

This study retrospectively analyzed data on pancreaticoduodenectomies completed by the same surgical group between January 2011 and April 2014 at our hospital. In these surgeries, a variety of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis methods were used, including single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis (referred to hereafter as single-layer anastomosis) and double-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis (referred to hereafter as double-layer anastomosis). Patients whose surgery involved either of these two pancreaticojejunal anastomosis methods in pancreaticoduodenectomy were enrolled, and patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria for the study were excluded. There were 102 patients in the two groups, with 51 cases in each group. Of these patients, 19 had hypertension, 14 had a history of diabetes mellitus, 30 had a past history of drinking, 27 had a history of smoking, and 14 cases had a history of abdominal surgery. There were 62 males and 40 females. Other general information on these patients is presented in Tables 1 and 2. All 102 cases were confirmed by postoperative pathology (Table 3).

| Item | Mean value | Standard deviation | Minimum value | Maximum value |

| Age (yr) | 58.804 | 9.466 | 38.000 | 79.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2 | 22.866 | 2.755 | 17.900 | 29.400 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.039 | 3.891 | 26.100 | 45.000 |

| Blood glucose (mol/L) | 6.472 | 2.540 | 3.960 | 16.610 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 122.618 | 122.204 | 6.400 | 412.600 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (u/L) | 359.631 | 258.629 | 39.900 | 1396.900 |

| r-GT | 620.853 | 522.464 | 7.000 | 2503.200 |

| Operation time (min) | 220.059 | 60.602 | 135.000 | 480.000 |

| Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time (min) | 17.922 | 5.145 | 11.000 | 40.000 |

| Amount of blood loss (mL) | 292.549 | 146.940 | 100.000 | 800.000 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter (mm) | 4.863 | 2.322 | 1.000 | 12.000 |

| Hospitalization time (d) | 25.627 | 6.551 | 15.000 | 49.000 |

| Postoperative hospitalization time (d) | 18.588 | 5.285 | 7.000 | 33.000 |

| Hospitalization expense (yuan) | 116787.667 | 31900.927 | 64874.000 | 237762.000 |

| Item | Mean value | Standard deviation | Minimum value | Maximum value |

| Age (yr) | 58.020 | 12.820 | 18.000 | 78.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.858 | 3.272 | 13.360 | 32.690 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39.480 | 4.182 | 29.600 | 50.000 |

| Blood glucose (mol/L) | 6.482 | 2.228 | 4.120 | 13.550 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 73.510 | 78.244 | 3.500 | 313.000 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (u/L) | 303.245 | 268.287 | 42.000 | 1105.600 |

| r-GT | 533.655 | 631.956 | 5.800 | 2744.000 |

| Operation time (min) | 379.412 | 90.761 | 210.000 | 570.000 |

| Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time (min) | 31.333 | 7.776 | 16.000 | 47.000 |

| Amount of blood loss (mL) | 482.353 | 293.909 | 50.000 | 1500.000 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter (mm) | 3.961 | 2.362 | 1.500 | 12.000 |

| Hospitalization time (d) | 33.706 | 15.899 | 16.000 | 105.000 |

| Postoperative hospitalization time (d) | 26.373 | 15.815 | 11.000 | 101.000 |

| Hospitalization expense (yuan) | 162788.608 | 129732.500 | 84497.000 | 968534.000 |

| Pathological type | Number of cases |

| Distal bile duct adenocarcinoma | 29 |

| Chronic inflammation at the end of the distal bile duct mucosa combined with moderate atypical dysplasia | 3 |

| Villous adenoma at the end of distal bile duct mucosa and moderate-severe atypical dysplasia of some glands | 1 |

| Ampullary adenocarcinoma | 14 |

| Duodenal stromal tumors | 1 |

| Adenocarcinoma of the descending duodenum | 3 |

| Duodenal papilla adenocarcinoma | 20 |

| Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors | 2 |

| Tubulovillous adenoma of duodenal papilla with severe atypical dysplasia of some epithelia | 1 |

| Duodenal papilla adenocarcinoma | 1 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | |

| Pancreatic head adenocarcinoma | 22 |

| Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of pancreatic head | 1 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor of pancreatic head | 2 |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma of pancreatic head | 1 |

General information: There were 51 patients in the double-layer anastomosis group. Sixteen of these received pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD); of these, 3 also received combined portal vein resection and reconstruction. Thirty-five patients received pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD); of these, 2 also received combined portal vein resection and reconstruction.

Surgical method: The pancreas was transected at the left side of the portal vein using a surgical knife. The bleeding points on the pancreatic resection surface were sutured and ligated using 6-0 PDS II for complete hemostasis. An appropriate pancreatic duct supporting tube was placed in the pancreatic duct. The pancreatic head was resected, and the duodenum and lymph nodes were completely cleaned. Approximately 2-3 cm of the pancreatic stump was freed, and an incision approximately 0.5 cm in length was made on the jejunal wall 4-5 cm from the jejunal stump. The distal end of the pancreatic duct supporting drainage tube was placed into the jejunum loop. The pancreatic parenchyma and the jejunal seromuscular layer were intermittently sutured using 4-0 Vicryl sutures; surgical knots were not made at this point. Next, 6-0 PDS IIabsorbable thread was used to intermittently penetrate the pancreatic duct and the jejunal opening to form the mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis using intermittent sutures for 6 stitches. One suture on the middle of the posterior wall was reserved to fix the pancreatic duct supporting tube. The intermittent suture between the pancreatic parenchyma and the jejunal seromuscular layer was ligated to complete the anastomosis. After the cholangioenteric anastomosis and gastrointestinal anastomosis were completed, two abdominal drainage tubes were inserted, one before and one after the pancreaticojejunal anastomotic site to facilitate postoperative observation and conventional monitoring of the quantity and properties of the drainage fluid and to provide samples for the measurement of indicators such as bilirubin and amylase.

General information: There were 51 patients in the single-layer anastomosis group. Twenty of these received PD; of these, 1 also received combined portal vein resection and reconstruction. Thirty-one of the patients in this group received PPPD; 1 of these also received combined portal vein resection and reconstruction.

Surgical method: The pancreas was transected at the left side of the portal vein using a small knife. The bleeding points on the pancreatic resection surface were sutured and ligated using 5-0 prolene sutures for complete hemostasis. Appropriate pancreatic duct supporting tubes were placed in the pancreatic duct. The pancreatic head was resected, and the duodenum and lymph nodes were completely cleaned.

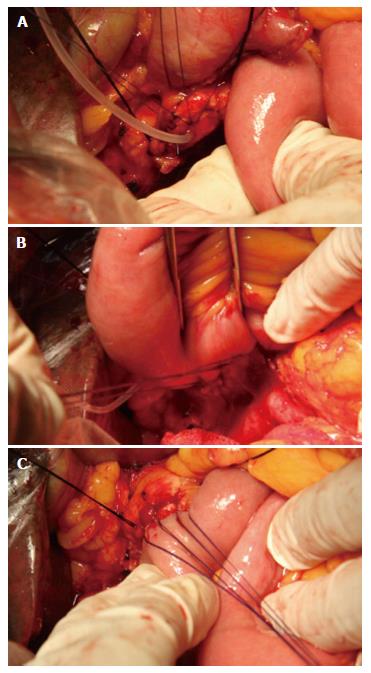

Step 1: The pancreatic stump was freed for approximately 3-4 cm of its length. At 1-2 cm from the pancreatic stump, the anterior wall of the pancreatic duct and the anterior wall of the pancreas were intermittently penetrated and sutured using 4-0 absorbable Vicryl sutures for 3-4 stitches; surgical knots were not made at this point, and the suture was reserved for suturing the anterior wall of the jejunal incision and for suspension of the anterior wall of the pancreatic duct. The needling direction was from the whole layer of the anterior wall of the pancreas to the inside of the anterior wall of the pancreatic duct (Figure 1A).

Step 2: The proximal jejunum was lifted, and a 0.5-0.8 cm incision was made at the jejunal wall 4-5 cm from the jejunal stump. A 4-0 absorbable Vicryl suture was used to intermittently penetrate and suture the whole layer of the posterior-lateral wall of the jejunum, the posterior-lateral wall of the pancreatic duct, and the whole layer of the posterior-lateral wall of the pancreas for a total of 5-7 stitches (3-5 stitches in the posterior wall and 1 stitch in each lateral wall). Surgical knots were not made at this point. The needling was conducted from outside the jejunum to the inside of the jejunal section for suturing; then, the posterior-lateral wall of the pancreatic duct and the whole layer of the posterior-lateral wall of the pancreas were penetrated and sutured. The knot was tied at one side. It is important to ensure that this knot is tied properly; if it is too tight, the pancreas and the pancreatic duct may be cut; if it is too loose, the attachment will be insufficient (Figure 1B).

Step 3: A supporting tube was placed in the jejunum with its distal end projecting over the mouth of the cholangioenteric anastomosis by approximately 5-8 cm. The anterior wall suspension suture was used to intermittently suture the whole layer of the anterior wall of the jejunum section; knots were then tied one by one to create an anastomosis between the pancreatic duct mucosa and the jejunal mucosa. After the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis was finished, the suture was ligated; at this point, an excellent attachment of the jejunum to the whole pancreatic stump could be observed (Figure 1C). After the cholangioenteric anastomosis and gastrointestinal anastomosis were completed, abdominal drainage tubes were placed at the inferior-posterior and superior-anterior sides of the pancreaticojejunal anastomotic site to facilitate postoperative observation and conventional monitoring of the quantity and properties of the drainage fluid and to provide samples for the measurement of indicators such as bilirubin and amylase.

After surgery, conventional infection prevention, nutrition, rehydration, and maintenance of water-electrolyte and acid-base balance were provided. All patients in both groups received total parenteral nutrition support. Conventional drugs for inhibition of pancreatic secretion were not administered after surgery. The amylase level in the drainage fluid at the pancreaticojejunal anastomotic site was measured 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 10 d after surgery. On postoperative day 7, abdominal computed tomography (CT) was conventionally performed. If no pancreatic fistula was present 10 d after surgery, the peritoneal drainage tube at the pancreaticojejunal anastomotic site was removed. In patients with pancreatic fistula, the peritoneal drainage tube was removed after the pancreatic fistula had healed.

Intraoperative blood loss, pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time, operation time, pancreatic fistula rate, abdominal infection rate, peritoneal catheterization rate, total complication rate, total hospitalization time, postoperative hospitalization time, and hospitalization expenses were recorded.

Pancreatic fistula was defined according to the ISGPF as output via operatively or postoperatively placed drains of any measurable volume of drainage fluid with amylase content greater than three times the upper normal serum value on or after postoperative day 3. Three grades of pancreatic fistula were determined according to the clinical severity of the individual cases. The grades were determined only after complete healing of the fistula had occurred[26].

Statistical analyses of the data on the patients in the two groups were performed using SPSS 17.0 software. Quantitative data that did not conform to a normal distribution or that had heterogeneous variances were examined using the non-parametric rank sum test. Qualitative data were examined using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact probability test. The examination level was α = 0.05. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

Gender, age, hypertension history, diabetes mellitus history, drinking history, smoking history, abdominal surgery history, preoperative biliary drainage, body mass index, total bilirubin, albumin, blood glucose, disease composition, surgical methods, jejunum-jejunum anastomosis (Braun anastomosis), pancreatic texture, and pancreatic duct diameter did not show significant differences in the two groups (Table 4).

| Item | Single-layer anastomosis group | Double-layer anastomosis group | P-value |

| Gender | Female: 21 | Female: 19 | 0.6850 |

| Male: 30 | Male: 32 | ||

| Age | > 60 yr: 24 | > 60 yr: 25 | 0.8429 |

| ≤ 60 yr: 27 | ≤ 60 yr: 26 | ||

| Hypertension | Yes: 6 | Yes: 13 | 0.0750 |

| No: 45 | No: 38 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes: 10 | Yes: 4 | 0.0843 |

| No: 41 | No: 47 | ||

| Drinking history | Yes: 14 | Yes: 16 | 0.6638 |

| No: 37 | No: 35 | ||

| Smoking history | Yes: 13 | Yes: 14 | 0.8224 |

| No: 38 | No: 37 | ||

| Abdominal surgery history | Yes: 5 | Yes: 8 | 0.3731 |

| No: 46 | No: 43 | ||

| Preoperative biliary drainage | Yes: 13 | Yes: 10 | 0.4772 |

| No: 38 | No: 41 | ||

| BMI | > 25: 13 | > 25: 17 | 0.3847 |

| ≤ 25: 38 | ≤ 25: 34 | ||

| Total bilirubin | > 171 μmol/L: 16 | > 171 μmol/L: 10 | 0.1728 |

| ≤ 171 μmol/L: 35 | ≤ 171 μmol/L: 41 | ||

| Serum albumin | ≥ 35 g/L: 40 | ≥ 35 g/L: 47 | 0.0503 |

| < 35 g/L: 11 | < 35 g/L: 4 cases | ||

| Blood glucose | > 6.1 mmol/L: 19 | > 6.1 mmol/L: 24 | 0.3161 |

| ≤ 6.1 mmol/L: 32 | ≤ 6.1 mmol/L: 27 | ||

| Disease composition | Pancreatic head: 11 | Pancreatic head: 16 | 0.5418 |

| Duodenum and papilla: 16 | Duodenum and papilla: 14 | ||

| Ampulla: 5 | Ampulla: 5 | ||

| Distal bile duct: 19 | Distal bile duct: 14 | ||

| Surgical method | PD: 20 | PD: 16 | 0.4072 |

| PPPD: 31 | PPPD: 35 | ||

| Braun anastomosis | Yes: 5 | Yes: 2 | 0.2400 |

| No: 46 | No: 49 | ||

| Pancreatic texture | Soft: 27 | Soft: 24 | 0.7918 |

| Normal or mild fibrosis: 14 Hard: 10 | Normal or mild fibrosis: 17 Hard: 10 | ||

| Pancreatic duct diameter | > 3 mm: 30 | > 3 mm: 26 | 0.4261 |

| ≤ 3 mm: 21 | ≤ 3 mm: 25 | ||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | Yes: 4 | Yes: 1 | 0.3590 |

| No: 47 | No: 50 |

Abdominal CT examination of 51 patients in the single-layer anastomosis group after surgery showed that the mouth of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and the surroundings did not have effusion. Abdominal CT examination of 51 patients in the double-layer anastomosis group after surgery showed that 6 cases had effusion surrounding the mouth of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. Table 5 shows the incidences of postoperative complications such as pancreatic fistula, peritoneal catheterization, abdominal infection, and total complications in the single-layer and double-layer anastomosis groups.

| Complication | Single-layer anastomosis group | Double-layer anastomosis group | χ2 | P-value |

| Pancreatic fistula | Yes: 13 | Yes: 35 | 19.0463 | 0.0000 |

| No: 38 | No: 16 | |||

| Peritoneal catheterization | Yes: 0 | Yes: 6 | 4.4271 | 0.0354 |

| No: 51 | No: 45 | |||

| Abdominal infection | Yes: 1 | Yes: 11 | 9.4444 | 0.0021 |

| No: 50 | No: 40 | |||

| Total complications | Yes: 21 | Yes: 37 | 10.2320 | 0.0014 |

| No: 30 | No: 14 |

In the single-layer anastomosis group, patients with pancreatic fistula accounted for 25.49% (13/51), patients with grade A pancreatic fistula accounted for 15.69% (8/51), and patients with grade B pancreatic fistula accounted for 9.80% (5/51); there were no patients with grade C pancreatic fistula. In the double-layer anastomosis group, patients with pancreatic fistula accounted for 68.63% (35/51), patients with grade A pancreatic fistula accounted for 15.69% (8/51), patients with grade B accounted for 45.10% (23/51), and patients with grade C accounted for 7.84% (4/51). In the single-layer anastomosis group, 10 of the 27 patients with soft pancreas had pancreatic fistula, 2 of the 14 patients with normal pancreatic texture or mild fibrosis of the pancreas had pancreatic fistula, and 1 of the 10 patients with hard pancreas had pancreatic fistula. In the double-layer anastomosis group, 21 of the 24 patients with soft pancreas had pancreatic fistula, 10 of the 17 patients with normal pancreatic texture or mild fibrosis of the pancreas had pancreatic fistula, and 4 of the 10 patients with hard pancreas had pancreatic fistula. A comparison of the incidence of pancreatic fistula in patients with different pancreatic textures is presented in Table 6.

| Pancreatic texture | Single-layer anastomosis group | Double-layer anastomosis group | χ2 | P-value |

| Soft | 10/27 | 21/24 | 13.5737 | 0.0002 |

| Normal or mild fibrosis | 2/14 | 10/17 | 0.0245 | |

| Hard | 1/10 | 4/10 | 0.3034 |

Because the intraoperative operation time, pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time, postoperative hospitalization time, total hospitalization time, and hospitalization expenses in the quantitative data of these two groups did not show normal distributions and/or exhibited heterogeneous variances, the data regarding these parameters were examined using the rank sum test to determine whether there were differences in these parameters between the two groups (Table 7).

| Item | Single-layer anastomosis group | Double-layer anastomosis group | Mann-Whitney | P-value |

| Operation time (min) | 220.059 (± 60.602) | 379.412 (± 90.761) | 179.000 | 0.000 |

| Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time (min) | 17.922 (± 5.145) | 31.333 (± 7.776) | 185.000 | 0.000 |

| Postoperative hospitalization time (d) | 18.588 (± 5.285) | 26.373 (± 15.815) | 854.500 | 0.003 |

| Total hospitalization time (d) | 25.627 (± 6.551) | 33.706 (± 15.899) | 841.000 | 0.002 |

| Hospitalization expense (yuan) | 116787.667 (± 31900.927) | 162788.608 (± 129732.500) | 800.000 | 0.001 |

The most important factor resulting in complications and deaths after pancreaticoduodenectomy was pancreatic fistula[13,26-28]. The tightness of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis to a large extent determines the success of pancreaticoduodenectomy. The modification of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis method and the improvement in surgical techniques described here can be used for pancreaticojejunal anastomotic leakage to reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistula. The single-layer pancreaticojejunal anastomosis method is a simple, reliable, and safe method for pancreaticojejunal anastomosis[29,30].

The single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis elucidated in this study is associated with pancreatic duct diameters ranging from 1-12 mm and a mean pancreatic duct diameter of 4.863 mm. We considered that when the pancreatic duct diameter was greater than 2 mm, single-layer pancreaticojejunal anastomosis was a better choice.

Single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is a simple and time-saving anastomosis method. It should be emphasized that during the process of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis, the suturing between the anterior wall of the pancreatic duct and the whole layer of the anterior wall of the pancreas, involving 3-4 stitches, should be conducted first, together with the suspension and opening of the pancreatic duct; this sequence is conducive to posterior wall suturing. During the suturing process, the distribution of needling should be even to prevent the formation of large spaces and the occurrence of non-strict pairing in some regions, which may cause pancreatic leakage. During the suturing of the anterior, lateral, and posterior walls of the duct, the needling site was approximately 1-2 cm from the pancreatic stump. To prevent damage to the pancreas and to small branches of the pancreatic ducts by multiple needling, which may cause pancreatic leakage, the needling for suturing the pancreas and the pancreatic duct should be conducted only once. The suturing method described here is simple and does not require sophisticated suturing techniques. The pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time in the single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis was 17.922 ± 5.145 min, and the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis time in the double-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis was 31.333 ± 7.776 min. The Mann-Whitney value for comparison of this parameter between the two groups was 185.000 (P = 0.000); thus, the difference in anastomosis time between the two groups was statistically significant, indicating that the single-layer anastomosis time was significantly lower than the double-layer anastomosis time.

Single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is a reliable pancreaticojejunal anastomosis method. The 51 patients in the single-layer anastomosis group received conventional upper abdominal CT examination 1 wk after surgery to determine the condition of the mouth of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and its surroundings; the results showed that neither the mouth of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis nor the surrounding area had effusion in any of the 51 patients. The 51 patients in the double-layer anastomosis group received conventional upper abdominal CT examination after 1 wk of surgery to display the condition of the mouth of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and its surroundings; the results showed that 6 patients had effusion at the mouth of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and/or in the surrounding area. A χ2 test of the data for the two groups yielded a χ2 value of 4.4271 (P = 0.0354); thus, the difference in the incidence of effusion in the two groups was statistically significant. In the single-layer anastomosis patients, the suture used for the anastomosis was tight, and the mouth of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and its surroundings did not show effusion after surgery. In the single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis, the jejunum completely covered the pancreatic section, and the resulting pressure on the pancreatic section and on the small pancreatic ducts within the pancreatic section contributed to hemostasis and thus reduced the risk of postoperative pancreatic section bleeding and pancreatic fistula. These results indicate that the application of single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis in pancreaticoduodenectomy is reliable.

The application of single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis in pancreaticoduodenectomy was shown to be safe. The pancreatic fistula rate in the single-layer anastomosis group was 25.45% (13/51), whereas the pancreatic fistula rate in the double-layer anastomosis group was 68.63% (35/51). A χ2 test of the data regarding the incidence of pancreatic fistula in the two groups yielded a χ2 value of 19.0464 (P = 0.0000). Thus, the difference between the two had statistical significance; the pancreatic fistula rate in the single-layer anastomosis group was lower than that in the double-layer anastomosis group.

Lin et al[31] summarized data from 1891 pancreaticoduodenectomy patients and concluded that soft pancreatic texture was the most important reason for the occurrence of pancreatic fistula. In our study, when the pancreatic texture was soft, the postoperative pancreatic fistula rate in the single-layer anastomosis group was 37.03% (10/27), whereas the rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula in the patients in the double-layer anastomosis group who displayed soft pancreatic texture was 87.50% (21/24). Comparison between the values obtained for the two groups yielded a χ2 value of 13.5737 (P = 0.0002). The difference was statistically significant, indicating that single-layer anastomosis was better than double-layer anastomosis when the pancreatic texture was soft. The use of single-layer anastomosis reduced the time needed for suturing the pancreas, reduced the damage to the pancreas, and decreased the incidence of pancreatic fistula. When the pancreatic texture was normal or the pancreas displayed mild fibrosis, the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula was 14.28% (2/14) in the single-layer anastomosis group and 58.82% (10/17) in the double-layer anastomosis group. Comparison of the difference between the two groups using the χ2 test and the Fisher exact probability test showed that the P-value was 0.0245, indicating that the difference between the two groups was statistically significant. For normal or mild fibrosis pancreatic texture, the pancreatic fistula rate in the single-layer anastomosis group was lower than that in the double-layer anastomosis group. In the single-layer anastomosis group, there were 5 cases of grade B pancreatic fistula, and the pancreatic fistula rate was 9.80%; there was no grade C pancreatic fistula in this group. In the double-layer anastomosis group, there were 23 cases of grade B pancreatic fistula, with a rate of 45.10%; in this group, there were 4 cases of grade C pancreatic fistula, with an incidence rate of grade C pancreatic fistula of 7.84%. Comparison of the incidences of grade B and grade C pancreatic fistula in the two groups yielded a χ2 value of 22.0393 (P = 0.0000), indicating that the difference between the two groups was statistically significant. The incidence of grade B and grade C pancreatic fistula in the single-layer anastomosis group was significantly lower than that in the double-layer anastomosis group.

In the single-layer anastomosis group, the rate of postoperative peritoneal catheterization was 0/51, and that of abdominal infection was 1/51. In the double-layer anastomosis group, the rate of postoperative peritoneal catheterization was 6/51, and the rate of abdominal infection was 11/51; the differences in these two parameters in the two groups were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The rates of postoperative peritoneal catheterization and abdominal infection in the single-layer anastomosis group were significantly lower than those in the double-layer anastomosis group. The total postoperative complication rate in the single-layer anastomosis group was 41.17% (21/51) and the total postoperative complication rate in the double-layer anastomosis group was 72.55% (37/51). A χ2 test comparing the data for the two groups yielded a χ2 value of 10.232 (P = 0.0014); thus, the difference between the two groups was statistically significant. The postoperative complication rate in the single-layer anastomosis group was lower than that in the double-layer anastomosis group. In summary, the foregoing data show that the application of the single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis in pancreaticoduodenectomy is safe.

Patients who experienced pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy had prolonged hospitalization time and increased hospitalization expenses[32]. The pancreatic fistula rate in the single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis group was lower than that in the double-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis group. In addition, postoperative hospitalization time, total hospitalization time, and hospitalization expenses were all lower in the single-layer anastomosis group than in the double-layer anastomosis group. The rank sum test results showed that the P-values for all of these comparisons were < 0.05; thus, the differences were statistically significant. These results indicate that postoperative hospitalization time, total hospitalization time, and hospitalization expenses were all lower in the single-layer anastomosis group than in the double-layer anastomosis group.

In summary, the results of this study show that single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is a simple, reliable, and safe anastomosis method. The use of this method could reduce the rates of postoperative pancreatic fistula, abdominal infection and peritoneal catheterization, overall complication rate, postoperative hospitalization time, total hospitalization time, and hospitalization expenses.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a standard treatment for various tumors of peri-ampullary region and pancreatic head. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a difficult surgery with a high perioperative complication rate and a high mortality rate. Pancreatic fistula is associated with delayed gastric emptying, intra-abdominal abscess, local infection at the incision site, sepsis, and blood loss postoperation. Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis plays an important role in pancreaticoduodenectomy; its success determines the success of the surgery.

Although the complication and mortality rates associated with pancreatic fistula have decreased due to improvements in surgical techniques, the incidence of postoperative complications during the perioperative period is still high. There are various pancreaticojejunal anastomosis procedures in pancreaticoduodenectomy, but so far none of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis procedures is regarded as best. No matter what kind of way of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis use in pancreaticoduodenectomy, pancreatic fistula is still high.

In this study, single-layer anastomosis group applied single layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis to pancreaticoduodenectomy. It should be emphasized that during the process of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis, the suturing between the anterior wall of the pancreatic duct and the whole layer of the anterior wall of the pancreas, involving 3-4 stitches, should be conducted first, together with the suspension and opening of the pancreatic duct; this sequence is conducive to posterior wall suturing. There was no knots inside of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. During the suturing process, the distribution of needling should be even to prevent the formation of large spaces and the occurrence of non-strict pairing in some regions, which may cause pancreatic leakage.

Single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is a simple pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. Surgeons can apply it to pancreaticoduodenectomy, especially when the pancreatic texture is soft. It can reduce the incidence rate of grade B and C pancreatic fistula and may reduce the mortality.

Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is essential and crucial anastomosis in pancreaticoduodenectomy. It plays an important role in pancreaticoduodenectomy; its success determines the success of the surgery. Single-layer mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunal anastomosis could help the surgeon to enhance the reliability of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis.

The article is an helpful and original research paper. It provides a new way of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis to surgeon in pancreaticoduodenectomy. The study is well designed, and the retrospective study was carried out at a very high accuracy and quality.

P- Reviewer: Ashley S, Mulvihill S

S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Callery MP, Pratt WB, Vollmer CM. Prevention and management of pancreatic fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:163-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhu B, Geng L, Ma YG, Zhang YJ, Wu MC. Combined invagination and duct-to-mucosa techniques with modifications: a new method of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:422-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Butturini G, Daskalaki D, Molinari E, Scopelliti F, Casarotto A, Bassi C. Pancreatic fistula: definition and current problems. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shrikhande SV, D'Souza MA. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: evolving definitions, preventive strategies and modern management. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5789-5796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, Ord SE, Sauter PK, Coleman J. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg. 1997;226:248-257; discussion 257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1357] [Cited by in RCA: 1388] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 6. | Reid-Lombardo KM, Farnell MB, Crippa S, Barnett M, Maupin G, Bassi C, Traverso LW. Pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1,507 patients: a report from the Pancreatic Anastomotic Leak Study Group. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1451-1458; discussion 1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lermite E, Pessaux P, Brehant O, Teyssedou C, Pelletier I, Etienne S, Arnaud JP. Risk factors of pancreatic fistula and delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:588-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schmidt CM, Choi J, Powell ES, Yiannoutsos CT, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Wiebke EA, Madura JA, Lillemoe KD. Pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy: clinical predictors and patient outcomes. HPB Surg. 2009;2009:404520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Büchler MW, Wagner M, Schmied BM, Uhl W, Friess H, Z'graggen K. Changes in morbidity after pancreatic resection: toward the end of completion pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1310-1314; discussion 1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hua YP, Liang LJ, Peng BG, Li SQ, Huang JF. Pancreatic head carcinoma: clinical analysis of 189 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:79-84. |

| 11. | Kimura W. Strategies for the treatment of invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas and how to achieve zero mortality for pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:270-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sewnath ME, Karsten TM, Prins MH, Rauws EJ, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of preoperative biliary drainage for tumors causing obstructive jaundice. Ann Surg. 2002;236:17-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Topal B, Aerts R, Hendrickx T, Fieuws S, Penninckx F. Determinants of complications in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:488-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang Q, Gurusamy KS, Lin H, Xie X, Wang C. Preoperative biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD005444. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Winter JM, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Alao B, Lillemoe KD, Campbell KA, Schulick RD. Biochemical markers predict morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1029-1036; discussion 1037-1038;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Erdmann J, van Eijck CHJ, Jeekel J. Standard resection of pancreatic cancer and the chance for cure. Am J Surg. 2007;194:S104-S109. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kleespies A, Albertsmeier M, Obeidat F, Seeliger H, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. The challenge of pancreatic anastomosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:459-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Connor S, Alexakis N, Garden OJ, Leandros E, Bramis J, Wigmore SJ. Meta-analysis of the value of somatostatin and its analogues in reducing complications associated with pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1059-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee SE, Ahn YJ, Jang JY, Kim SW. Prospective randomized pilot trial comparing closed suction drainage and gravity drainage of the pancreatic duct in pancreaticojejunostomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:837-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Grobmyer SR, Kooby D, Blumgart LH, Hochwald SN. Novel pancreaticojejunostomy with a low rate of anastomotic failure-related complications. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sugiyama M, Suzuki Y, Abe N, Ueki H, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Pancreatic duct holder for facilitating duct-to-mucosa pancreatojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2009;197:e18-e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kakita A, Yoshida M, Takahashi T. History of pancreaticojejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy: development of a more reliable anastomosis technique. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:230-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Payne RF, Pain JA. Duct-to-mucosa pancreaticogastrostomy is a safe anastomosis following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:73-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Peng SY, Wang JW, Lau WY, Cai XJ, Mou YP, Liu YB, Li JT. Conventional versus binding pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:692-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kimura W. Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis, using a stent tube, in pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:305-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3512] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 27. | Aranha GV, Hodul PJ, Creech S, Jacobs W. Zero mortality after 152 consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:223-231; discussion 231-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rezvani M, O'Moore PV, Pezzi CM. Late pancreaticojejunostomy stent migration and hepatic abscess after Whipple procedure. J Surg Educ. 2007;64:220-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kwon YJ, Ahn BK, Park HK, Lee KS, Lee KG. One layer end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy using reinforcing suture on the pancreatic stump. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1488-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Furuta K, Yoshida M, Itabashi K, Katagiri H, Ishii K, Takahashi Y, Watanabe M. The advantage of Kakita's method with pancreaticojejunal anastomosis for pancreatic resection. Surg Technol Int. 2008;17:150-155. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:951-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Čečka F, Jon B, Šubrt Z, Ferko A. Clinical and economic consequences of pancreatic fistula after elective pancreatic resection. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |