Published online Oct 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.254

Peer-review started: June 5, 2015

First decision: June 18, 2015

Revised: August 21, 2015

Accepted: September 1, 2015

Article in press: September 2, 2015

Published online: October 27, 2015

Processing time: 151 Days and 6.3 Hours

AIM: To describe our experience concerning the surgical treatment of Strasberg E-4 (Bismuth IV) bile duct injuries.

METHODS: In an 18-year period, among 603 patients referred to our hospital for surgical treatment of complex bile duct injuries, 53 presented involvement of the hilar confluence classified as Strasberg E4 injuries. Imagenological studies, mainly magnetic resonance imaging showed a loss of confluence. The files of these patients were analyzed and general data were recorded, including type of operation and postoperative outcome with emphasis on postoperative cholangitis, liver function test and quality of life. The mean time of follow-up was of 55.9 ± 52.9 mo (median = 38.5, minimum = 2, maximum = 181.2). All other patients with Strasberg A, B, C, D, E1, E2, E3, or E5 biliary injuries were excluded from this study.

RESULTS: Patients were divided in three groups: G1 (n = 21): Construction of neoconfluence + Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy. G2 (n = 26): Roux-en-Y portoenterostomy. G3 (n = 6): Double (right and left) Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy. Cholangitis was recorded in two patients in group 1, in 14 patients in group 2, and in one patient in group 3. All of them required transhepatic instrumentation of the anastomosis and six patients needed live transplantation.

CONCLUSION: Loss of confluence represents a surgical challenge. There are several treatment options at different stages. Roux-en-Y bilioenteric anastomosis (neoconfluence, double-barrel anastomosis, portoenterostomy) is the treatment of choice, and when it is technically possible, building of a neoconfluence has better outcomes. When liver cirrhosis is shown, liver transplantation is the best choice.

Core tip: Strasberg E-4 (Bismuth IV) bile duct injuries represent a surgical challenge. These injuries which involve two separated right and left ducts are of multifactorial etiology, and may be the result of ischemic or thermal damage, an inflammatory reaction, or anatomical variants that predispose the patient to injury. The treatment options are many, mainly surgical. Best results are obtained with Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomies, as we describe in this article.

- Citation: Mercado MA, Vilatoba M, Contreras A, Leal-Leyte P, Cervantes-Alvarez E, Arriola JC, Gonzalez BA. Iatrogenic bile duct injury with loss of confluence. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(10): 254-260

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i10/254.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.254

Bile duct injuries following laparoscopic approach have been extensively studied. Several classifications have been developed to describe both the mechanism by which the injury occurs and the anatomic result. Classification of these injuries is challenging, although possible, since each lesion is not only anatomically unique, but also the final result of several factors, such as duct ischemia, thermal injury and ablation, and transection of the duct. These injuries have been found to have a constant rate, regardless of the surgeon’s experience or the hospital (0.3%-0.6%).

One of the most feared types of injury is that which involves the confluence. They are classified as Bismuth IV and Strasberg E4 injuries, and represent a surgical and multidisciplinary challenge (Figure 1). Loss of the confluence, in which one or two right ducts are separated from the left duct, represent a technical challenge with several therapeutic options. These include various types of bilioenteric anastomosis as well as major hepatectomy. Here we describe our experience with this type of injury and the results of our surgical treatment, which in most instances, is the only option available to treat this type of injuries.

During an 18-year period we studied 603 patient candidates for surgical treatment of iatrogenic bile duct injury. The conditions in which these patients arrived at our center are highly variable; each patient has an individual history and timeline. Several have received previous endoscopical, radiological, or surgical therapy.

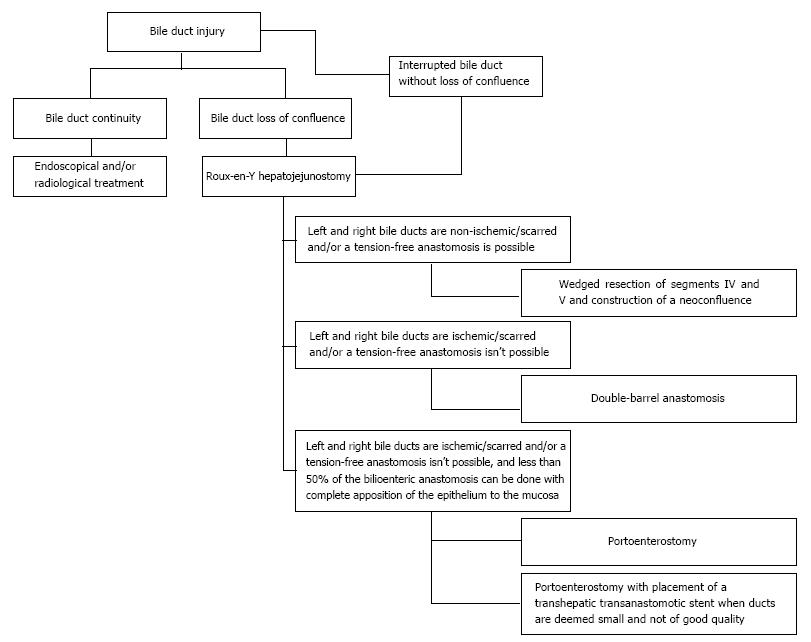

Patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary group that selects patients with ductal continuity for endoscopical and/or radiological treatment. Those with loss of continuity are selected for surgical management. Patient selection and injury classification are carried out based on results of several imaging studies, including magnetic resonance cholangiography, computerized tomography, and ultrasound. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography is selectively performed on patients in whom there is a suspicion of a lateral injury that can be resolved with a stent. Patients who arrive with acute cholangitis, or in whom injury classification cannot be determined, are studied by percutaneous cholangiography. Surgery is programmed according to the general condition of the patient. When patients present multiple organ failure and/or evident sepsis, the procedure is delayed as long as needed. Until the general condition of the patient improves, percutaneous or surgical placement of a drain is the treatment of choice. Injuries are classified according to the Strasberg and Bismuth classifications.

All cases in which there is loss of duct continuity and thickness, duct transection is treated surgically by means of a Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy. The type and characteristics of the anastomosis have been described previously[1,2].

Medical records of all patients in whom loss of confluence was found (injuries classified as Bismuth IV, Strasberg E4) were analyzed and their general data were recorded. Type of surgical procedure, postoperative outcome with emphasis on postoperative cholangitis, liver function tests, and quality of life were also recorded. The mean time of follow-up of these patients was of 55.9 ± 52.9 mo (median = 38.5, minimum = 2, maximum = 181.2). For analysis purposes, patients were divided into three groups according to type of surgical repair. These groups and their characteristics are described on Table 1.

| Group | Surgical procedure to repair loss of confluence | n (%) |

| G1 | Construction of neo-confluence + Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy | 21 (40%) |

| G2 | Roux-en-Y Portoenterostomy | 26 (49%) |

| G3 | Separated (right and left) Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy | 6 (11%) |

Among the 603 cases of biliary duct injuries, 53 cases with loss of confluence were identified. Most of the cases had a preoperative external biliary fistula (n = 27) with different types of abdominal or percutaneous drains. There was a wide range of time between the index surgery (where the injury was produced) and the attempts to repair in our institution (mean 14 d). In 28 cases the diagnosis of loss of confluence was established preoperatively through the imaging methods mentioned, with magnetic resonance cholangiography being the method of choice for injury classification, as it has been for the last 10 years. If bilomas, abscesses, and/or fluid collection were identified, drainage (usually percutaneously) was carried out.

During the surgical procedure, loss of confluence was confirmed after completely dissecting the porta hepatis and lowering the hilar plate to expose the right and left ducts. In all cases, a 40 cm long Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy was performed.

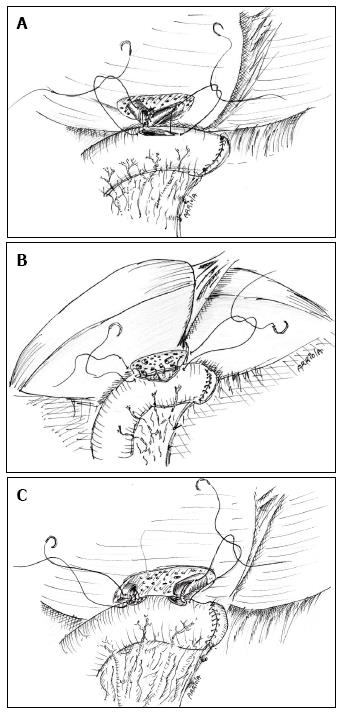

In 21 cases, after a wedged resection of segments IV and V over the hilar plate, and after identification of the right and left ducts, a neo-confluence was constructed with fine everted stiches with a 6-0 hydrolysable monofilament. Also, the anterior aspect of the left duct (if necessary the right duct as well) was opened in order to obtain a wide, tension-free bilio-intestinal anastomosis that included the neo-confluence (Figure 2A).

Twenty-six patients were treated by means of a Roux-en-Y portoenterostomy: after partial resection of segments IV and V the two ducts were found separated and partially scarred and/or ischemic. In 9 of these cases a transhepatic transanastomotic stent was placed; in the remaining 17 no stent was placed. These were considered as portoenterostomies since in more than 50% of the circumference of the anastomosis a high quality bilioenteric anastomosis was not achieved due that the biliaryepithelium could not be joined with the intestinal mucosa (Figure 2B).

The 9 cases in which stents were placed have had an adequate postoperative evolution without symptoms and cholangitis. Stents were removed between the 6th and the 9th postoperative months. In two cases they were left in place longer, one for 12 mo due to patient non-compliance, and one for 84 mo due to patient’s request. After this, the patients were left without a stent. In the other 7 patients whose stent was removed, 4 remained asymptomatic, 1 patient died in the fourth postoperative year because of secondary biliary cirrhosis, 1 patient in whom cirrhosis and liver failure were recorded was lost to follow-up, and 1 has developed cirrhosis and jaundice.

In 6 cases, both ducts were identified, but construction of a neo-confluence was not possible. Therefore, a double-barrel anastomosis was performed. Three of these patients remained asymptomatic in the postoperative period (mean 6 years, range 3-12). Two cases required a right hepatectomy several months after the reconstruction because of persistent sectionary (unilobar) cholangitis. They are currently doing well, with patent bilioenteric anastomosis. One patient had persistent cholangitis and developed cirrhosis in the 4th postoperative year after one reoperation and attempts to perform radiological percutaneous dilation and surgical and radiological placement of stents (Figure 2C).

Figure 3 shows a summary of the surgical treatment strategy followed for bile duct injuries with loss of confluence.

The frequency of perioperative complications in patients treated by means of a Roux-en-Y portoenterostomy (group 2) was of 57.6%. The postoperative complications of these patients according to the Clavien-Dindo grading system are shown in Table 2.

| Classification | Frequency (%) | Description (frequency) |

| I | 1 (3.8%) | Superficial surgical site infection (1) |

| II | 7 (26.9%) | Intra-abdominal collection not requiring surgical intervention (5) |

| Superficial surgical site infection not requiring surgical intervention (1) | ||

| Cholangitis (1) | ||

| IIIa | 0 (0%) | - |

| IIIb | 3 (11.5%) | Intra-abdominal collection requiring surgical intervention (1) |

| Biliary anastomosis remodeling (1) | ||

| Intra-abdominal collection requiring transendoscopic ultrasound drainage (1) | ||

| IVa | 3 (11.5%) | Septic shock (3) |

| IVb | 0 (0%) | - |

| V | 1 (3.8%) | Atrioventricular block (1) |

Sixteen (61.5%) group 2 patients presented cirrhosis during follow-up, while 10 (38.4%) haven’t developed cirrhosis to the last moment of follow-up. Thirteen patients (50%) have been referred for hepatic transplant evaluation, and 3 (11.5%) haven’t been sent because of compensated cirrhosis.

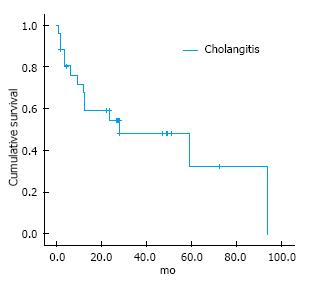

On the other hand, 14 (53.8%) group 2 patients developed cholangitis. The cholangitis free survival rate was of 45 ± 9.17 mo (95%CI: 27.1-63) as shown in Figure 4.

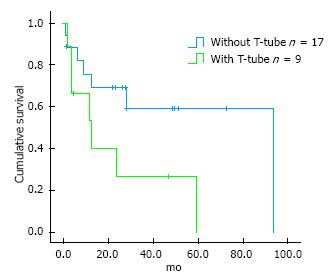

Of these patients, 4 out of 9 patients in which a T-tube was placed (44.5%) required percutaneous interventions after their removal. Two patients (22.2%) needed the placement of an internal-external biliary drainage catheter after removal of the T-tube, while in the other 2 patients (22.2%) the T-tube was replaced with a percutaneous biliary catheter which wasn’t removed until 11.1 mo after.

Four patients out of the 17 in which a T-tube wasn’t placed (65.3%) required the placement of an internal-external biliary drainage. Only one of them (25%) is free of drainages at 63.7 mo.

Seven (77.8%) group 2 patients in which a T-tube was placed developed cholangitis during follow-up. Those in which a T-tube wasn’t placed, 7 (41.2%) presented this complication. Nonetheless, there was no significant difference between these two subgroups (P = 0.075). Cholangitis free survival rate tended to be greater in those patients without placement of a T-tube (60.1 ± 11.6 mo, 95%CI: 37.4-82.9; vs 23.1 ± 8.6, 95%CI: 6.2-40; log-rank P = 0.056) (Figure 5).

Surgical treatment of bile duct injury is indicated when loss of duct continuity is found and endoscopic and/or radiological approach is ruled out[2]. Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy has been proven to be the best treatment option by several groups[3]. A high quality bilioenteric anastomosis, which is defined as tension-free, wide, with adequate suture material, done in healthy, non-scarred non-ischemic ducts that are anastomosized to an afferent Roux-en-Y jejunal limb, offers the best results[4]. There are several technical maneuvers that can be done in order to reach this goal, including the anterior opening of the confluence and the left duct, as well as partial removal of segments IV and V[5,6].

Our group has shown that an anastomosis done in a patient with preserved confluence offers the best results[7]. These results can be also optimized if the patient has no stones or sludge, usually the result of secondary colonization of bile.

Loss of confluence, depicted in Bismuth classification as IV and in Strasberg classification as E-4, is one of the most feared scenarios for surgeons, because of the technical challenge that it represents.

Loss of confluence can be the result of several issues. In some instances, it is the result of an anatomical variation in which the given patient has a low extrahepatic confluence that is injured during dissection, and also in subsequent section, transection or occlusion of the duct can be performed at this level. There is no available data on how many individuals have a low extrahepatic confluence. In the majority of people the confluence, although extrahepatic, is not low. In these cases, loss of confluence is the result of ischemic damage, thermal damage or both.

After section of the common duct, the proximal stump (near to the plane of section) becomes ischemic. It has been stated by Strasberg et al[5] that one of the key features for successful repair and successful bilio-enteric anastomosis is to wait enough time, so that the injury stabilizes and the exact level of duct ischemia is reached[8]. So, in some cases the ischemia level reaches the confluence. Bismuth has also stated that the level of the injury is always higher than it is appreciated in the initial stump[9].

In other cases, loss of confluence is the consequence of the local inflammatory reaction produced by either bile leakage or drains placed for a long time in the common duct, which lead to consequent destruction. This is especially true when patients in whom a non-silastic drain is placed subhepatically and fixed to the bile duct, establishing an external fistula, are referred late. Right hepatic arterial injuries are usually seen in this type of injury. Stewart et al[10] have shown that the higher the injury the higher the probability of arterial damage. They have also shown that this has no impact in the final results of reconstruction, with the condition that the procedure is done by an interested and experienced hepatobiliary surgeon. In some cases, the artery can be reconstructed[11] by carrying out a primary anastomosis or planning an interposition graft. In our experience these arteries are not suitable for repair. The circulatory status of the ducts at the confluence level has a vascular net that allows a compensatory supply from the left to the right. This is why an anastomosis done at the confluence level warrants a good result, regardless of the patency of the right artery.

Ischemia of the duct is usually secondary to the type of the dissection inherent to the laparoscopic procedure. The common duct is easily confused with the cystic duct, and lateral traction of it causes damage to the small duct lateral vessels. Also, thermal injury is more likely because the higher the dissection goes, small bleedings can be found that are cauterized via thermal energy. In every repair, we do everything possible in order to cannulate the right and left hepatic ducts for identification purposes. In some of these cases we have found isolated right posterior injuries, with the right anterior duct reaching the left duct.

In some cases the separated duct can be reunited by removing the adjacent parenchyma and placing everted stitches that allow the construction of a neoconfluence. This could be done in 6 of the 37 cases (17%). There are other cases in which this maneuver could not be done and a portoenterostomy was constructed. Pickleman et al[12] published their experience obtaining good results with this type of approach. Some of our cases required placement of a transhepatic transanastomotic stent. The decision to place them was made according to the characteristics of the duct found at the time of operation. In our first three cases treated by means of portoenterostomy, we observed a difficult postoperative evolution. In other cases, it was deemed that a hepatectomy was necessary because of the characteristics of the duct and the lobe. In these two cases, a right hepatic injury was shown so that the lobectomy was done with a left duct jejunostomy. Laurent et al[13] have shown that in 15% of their cases with a complete injury a major hepatectomy was required, and resulted in excellent postoperative results. For cases with major vascular injury and bad quality major ducts, hepatectomy must be considered.

In other cases, the construction of two separated anastomosis could be done. This approach was selected when adequate separated ducts were found.

Rebuilding the confluence is not always possible. After removal of the liver parenchyma at the hilar level, both ducts are identified at the hilar plate. It is very important not to manipulate the ducts excessively because of the danger of devascularization. When both ducts are deemed “healthy”, a tension free approximation of the posterior lateral edge of the left duct is done to the medial aspects of the right duct. Usually with three to four everted stitches the approximation is obtained. The anterior aspect of the left duct is opened and then an anastomosis to the jejunal limb (almost in a side to side fashion) is done. If the ducts are ischemic and/or the approximation of both foramens is not tension free, the surgeon must decide to do separate anastomosis of the ducts to the jejunum.

When a two anastomoses approach is decided, our preference is to open the anterior aspect of the left duct as well as right one in the same fashion, as described by Strasberg et al[5].

Portoenterostomy is decided when it is deemed that less than 50% of the anastomosis is done with complete apposition of the epithelium to the mucosa. Everted stitches are placed between the jejunal mucosa and the bile duct where it is possible and the remaining part of the anastomosis is done to the liver capsule and/or parenchyma.

The decision to place a transanastomotic stent is always difficult. When our group first started, we decided to place stents in all cases, but we evolved to selective placing when needed[14], specifically when ducts were deemed small and not of good quality. As we have stated, each patient has an individual type of injury and resulting anatomy.

Overall, considering all the treatments modalities, the procedure was successful in 88% of the cases, obtaining good postoperative results without cholangitis, good quality of life and without requiring reintervention.

In conclusion, an injury that includes the loss of confluence of the duct represents a surgical challenge. There are several options to be considered (neoconfluence, double-barrel anastomosis and portoenterostomy) that must be shaped and selected according to the individual characteristics of a given patient.

One of the most complex bile duct injuries is that which involves the loss of confluence of the right and left bile ducts, namely a Strasberg E-4 injury. Initially, the authors’ team’s surgical approach to this problem was the forming of a double-barrel anastomosis; however, it resulted in long term dysfunction. By descending the hilar plate, performing a partial resection of segment IV, and liberating both bile ducts so as to approximate them and include them in a single anastomosis, the outcomes seen in these patients became comparable to those in patients in which the confluence was preserved.

Many surgical treatments for loss of confluence bile duct injuries have been proposed, including the creation of a two-barrel anastomosis, a portoenterostomy, or a neoconfluence. Few have described results regarding any of these reconstructions.

To our knowledge, this is the first retrospective study that analyzes long term outcomes of neoconfluences in iatrogenic bile duct injuries. They have only been described in Blumgart’s textbook of hepatic and biliary surgery, although without mentioning the removal of segment IV, which the authors consider necessary to facilitate the construction of an anastomosis.

Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomies offer the best outcomes in patients with bile duct injuries with loss of confluence, as reported in the authors’ observations. Individual characteristics of the patient must be taken into account in order to decide the most suitable surgical approach, although creating a neoconfluence should be of top priority.

Bile duct injuries represent all deleterious consequences on the intra- or extrahepatic bile ducts, as a result of the removal of the gallbladder or of any endoscopic and surgical instrumentation of the ducts. Cholangitis is one of the most important complications that arise from these injuries, usually due to inflammation and fibrosis caused by biliary leaks.

The manuscript is interesting and well written.

P- Reviewer: Kuwatani M, Kassir R S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Mercado MA, Orozco H, de la Garza L, López-Martínez LM, Contreras A, Guillén-Navarro E. Biliary duct injury: partial segment IV resection for intrahepatic reconstruction of biliary lesions. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1008-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chapman WC, Abecassis M, Jarnagin W, Mulvihill S, Strasberg SM. Bile duct injuries 12 years after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:412-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Coleman J, Sauter PA. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:786-792; discussion 793-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mercado MA, Orozco H, Chan C, Quezada C, Barajas-Olivas A, Borja-Cacho D, Sánchez-Fernandez N. Bile duct growing factor: an alternate technique for reconstruction of thin bile ducts after iatrogenic injury. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1164-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Strasberg SM, Picus DD, Drebin JA. Results of a new strategy for reconstruction of biliary injuries having an isolated right-sided component. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:266-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Villalta JM, Barajas-Olivas A, Eraña J, Domínguez I. Long-term evaluation of biliary reconstruction after partial resection of segments IV and V in iatrogenic injuries. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Hinojosa CA, Podgaetz E, Ramos-Gallardo G, Gálvez-Treviño R, Valdés-Villarreal M. Prognostic implications of preserved bile duct confluence after iatrogenic injury. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:40-44. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Mercado MA. Early versus late repair of bile duct injuries. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1644-1647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bismuth H, Majno PE. Biliary strictures: classification based on the principles of surgical treatment. World J Surg. 2001;25:1241-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stewart L, Robinson TN, Lee CM, Liu K, Whang K, Way LW. Right hepatic artery injury associated with laparoscopic bile duct injury: incidence, mechanism, and consequences. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:523-530; discussion 530-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li J, Frilling A, Nadalin S, Paul A, Malagò M, Broelsch CE. Management of concomitant hepatic artery injury in patients with iatrogenic major bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:460-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pickleman J, Marsan R, Borge M. Portoenterostomy: an old treatment for a new disease. Arch Surg. 2000;135:811-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Laurent A, Sauvanet A, Farges O, Watrin T, Rivkine E, Belghiti J. Major hepatectomy for the treatment of complex bile duct injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Cano-Gutiérrez G, Chaparro JM, Galindo E, Vilatobá M, Samaniego-Arvizu G. To stent or not to stent bilioenteric anastomosis after iatrogenic injury: a dilemma not answered? Arch Surg. 2002;137:60-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |