Published online Jun 27, 2014. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v6.i6.94

Revised: February 14, 2014

Accepted: May 15, 2014

Published online: June 27, 2014

Processing time: 230 Days and 10.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate pathological factors related to long term patient survival post surgical management of gastric adenocarcinoma in a Caribbean population.

METHODS: This is a retrospective, observational study of all patients treated surgically for gastric adenocarcinoma from January 1st 2000 to December 31st 2010 at The University Hospital of the West Indies, an urban Jamaican hospital. Pathological reports of all gastrectomy specimens post gastric cancer resection during the specified interval were accessed. Patients with a final diagnosis other than adenocarcinoma, as well as patients having undergone surgery at an external institution were excluded. The clinical records of the selected cohort were reviewed. The following variables were analysed; patient gender, patient age, the number of gastrectomies previous performed by the lead surgeon, the gross anatomical location and appearance of the tumour, the histological appearance of the tumour, infiltration of the tumour into stomach wall and surrounding structures, presence of Helicobacter pylori and the presence of gastritis. Patient status as dead vs alive was documented for the end of the interval. The effect of the aforementioned factors on patient survival were analysed using Logrank tests, Cox regression models, Ranksum tests, Kruskal-Wallis tests and Kaplan-Meier curves.

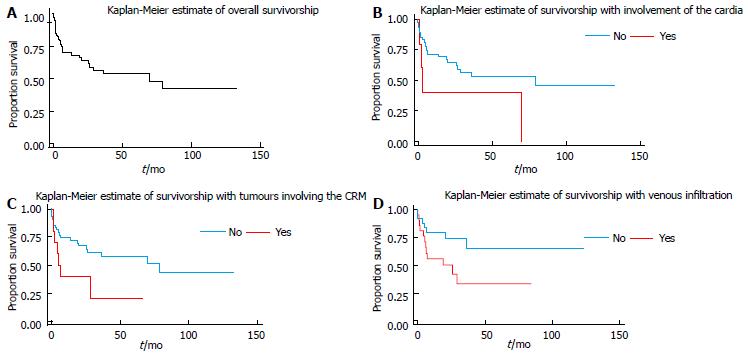

RESULTS: A total of 79 patients, 36 males and 43 females, were included. Their median age was 67 years (range 36-86 years). Median survival time from surgery was 70 mo with 40.5% of patients dying before the termination date of the study. Tumours ranged from 0.8 cm in size to encompassing the entire stomach specimen, with a median tumour size of 6 cm. The median number of nodes removed at surgery was 8 with a maximum of 28. The median number of positive lymph nodes found was 2, with a range of 0 to 22. Patients’ median survival time was approximately 70 mo, with 40.5% of the patients in this cohort dying before the terminal date. An increase in the incidence of cardiac tumours was noted compared to the previous 10 year interval (7.9% to 9.1%). Patients who had serosal involvement of the tumour did have a significantly shorter survival than those who did not (P = 0.017). A significant increase in the hazard ratio (HR), 2.424, for patients with circumferential tumours was found (P = 0.044). Via Kaplan-Meier estimates, the presence of venous infiltration as well as involvement of the circumferential resection margin were found to be poor prognostic markers, decreasing survival at 50 mo by 46.2% and 36.3% respectively. The increased HR for venous infiltration, 2.424, trended toward significant (P = 0.055) Age, size of tumour, number of positive nodes found and total number of lymph nodes removed were not useful predictors of survival. It is noted that the results were mostly negative, that is many tumour characteristics did not indicate any evidence of affecting patient survival. The current sample, with 30 observed events (deaths), would have about 30% power to detect a HR of 2.5.

CONCLUSION: This study mirrors pathological factors used for gastric cancer prognostication in other populations. As evaluation continues, a larger cohort will strengthen the significance of observed trends.

Core tip: This ten year retrospective analysis of pathologic factors affecting the survival of gastric cancer patients is the first ever to be done in a Caribbean population. Significant findings meriting publication include increasing incidence of proximal tumours and decreased survival with involvement of the circumferential resection margin. Among other factors also examined, are the impact of surgeon and pathologist training on patient survival. By describing the current state of gastric cancer management in this population, this study aspires to lay the foundation for further work enhancing gastric cancer care in this region.

- Citation: Roberts PO, Plummer J, Leake PA, Scott S, Souza TG, Johnson A, Gibson TN, Hanchard B, Reid M. Pathological factors affecting gastric adenocarcinoma survival in a Caribbean population from 2000-2010. World J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 6(6): 94-100

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v6/i6/94.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v6.i6.94

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common malignancy in men, and the fifth commonest in women diagnosed worldwide[1]. In Jamaica it is the seventh commonest cancer in men and the ninth most common in women[2]. Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third most frequent cause of cancer death in men and the fifth most common in women[1]. In Jamaica it is the fourth leading cause of cancer related death[3].

These figures prompt scrutiny and characterization of the Jamaican gastric cancer patient population. Accordingly, Plummer et al[4] had previously outlined age and sex related incidence, histological appearance, as well as tumour location in a surgically treated cohort of gastric adenocarcinoma patients in Jamaica from 1993-2002, and found that the antrum of the stomach was most often involved, with a trend toward increased incidence of more proximal tumours in the latter 5 years studied, and that lymph node metastases were common[4].

It was our aim to build on this base of information and to explore prognostication in this patient demographic. Our study seeks, for the first time in the Jamaican population, to describe the post-surgical survival rate of gastric adenocarcinoma patients and to elucidate related pathological factors.

This retrospective, observational study summarizes the analyses conducted on patients diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI) from 2000 to 2010. Analysis was conducted using STATA 9. Approval was granted from the Ethics Committee of the hospital (file number ECP334, 12/13). This study was carried out in accordance with the Second International Helsinki Declaration[5].

All patients who were diagnosed with gastric cancer at UHWI during the period January 1st 2000 to December 31st 2010 were enrolled via review of pathology reports. UHWI is a type A teaching hospital and a referral centre, accepting the management of patients exceeding the resource capability of several smaller hospitals throughout Jamaica. These patients had all been seen at the General Surgery outpatient clinic, and subsequently undergone upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy proving gastric cancer. Other forms of gastric cancer besides adenocarcinoma were excluded. Patients with a final diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma, but who had undergone surgery at other institutions were excluded. This exclusion came as a matter of access to the clinical records of those patients. Demographically, the patients receiving definitive management at external institutions are not anticipated to greatly differ from the patient population investigated in this study. Of note, the population of Jamaica is predominantly Afro-Caribbean.

Survival data was analysed with the event being death and the time to death being defined as the time in months from surgery until the patient’s death. Persons who did not die were censored at the date of their last visit or if confirmed to be alive, they were censored at December 31, 2011.

Logrank tests were conducted to determine whether the survival rate was different across various groupings within variables. Cox regression models were built to determine whether various pathological characteristics would be able to predict a person’s risk of death. Ranksum tests as well as Kruskal-Wallis tests of association were done to determine whether the relationships between clinicopathological factors and survival were different for persons who were dead as opposed to confirmed alive or censored prior to the end of the studied interval[6,7].

The surgical notes and pathological reports of the 79 patients meeting the criteria of histologically identified gastric adenocarcinoma, and having had D1 gastrectomy at UHWI were reviewed. There were more females (54.4%) than males (Table 1). The median age of the patients was 67 years with a range of 36 to 86 years. Tumours ranged from 0.8 cm in size to encompassing the entire stomach specimen, with a median tumour size of 6 cm. The median number of nodes removed at surgery was 8 with a maximum of 28. Four specimens included 15 or more lymph nodes. Seventy-seven specimens were found to have nodal metastasis. The median number of positive lymph nodes found was 2, with a range of 0 to 22. Patients’ median survival time was approximately 70 mo, with 40.5% of the patients in this cohort dying before the terminal date (Table 1). A total of 47 patients were censored, with 7 of those being censored at the end of the study, i.e., confirmed to be still living as at December 31, 2011.

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 36 (45.6 ) |

| Female | 43 (54.4 ) | |

| Number of previous gastrectomies by surgeon | < 10 | 30 (38.0 ) |

| > 10 | 49 (62.0) | |

| Patient status | Alive | 7 (8.9) |

| Censored | 40 (50.6) | |

| Dead | 32 (40.5) |

In this series, thirty-eight percent of the surgeries were performed by doctors who had performed less than 10 gastrectomies, while the other 62% were performed by surgeons who had performed 10 or more (Table 1) . Approximately a quarter (24.7%) of patients had tumours situated on the lesser curvature of the stomach while about half that number (11.7%) had tumours involving the greater curvature. The most common anatomical location was the antrum (54%), followed by the pylorus (37.7%). Fifteen point six percent of patients had tumours located on the anterior wall of the stomach, 24.7% on the posterior wall, and 16.9% were circumferential (Table 2).

| Location of tumour | n = 79 | |

| Lesser curvature | Uninvolved | 60 (75.3) |

| Involved | 19 (24.7) | |

| Greater curvature | Uninvolved | 70 (88.3) |

| Involved | 9 (11.7) | |

| Antrum | Uninvolved | 35 (45.5) |

| Involved | 34 (54.5) | |

| Pylorus | Uninvolved | 49 (62.3) |

| Involved | 50 (37.7) | |

| Body | Uninvolved | 62 (79.2) |

| Involved | 17 (20.8) | |

| Cardia | Uninvolved | 71 (90.9) |

| Involved | 8 (9.1) | |

| Fundus | Uninvolved | 73 (92.2) |

| Involved | 6 (7.8) | |

| Anterior wall | Uninvolved | 66 (84.4) |

| Involved | 13 (15.6) | |

| Posterior wall | Uninvolved | 59 (75.3) |

| Involved | 20 (24.7) | |

| Circumferential | Uninvolved | 66 (83.1) |

| Involved | 13 (16.9) | |

Histologically, less than half of the patients had tumours that were diffuse, while a little more than half (57.4%) were intestinal. Most (43.2%) patients had low grade tumours compared to 32.4% having tumours of moderate grade and the remainder of high grade. More than half of the patients had ulcerative lesions. Few (5.7%) had tumours that were well differentiated, while the majority (50.9%) of patients had tumours that were moderately differentiated. Ninety-six percent of tumours were advanced with involvement of muscularis propria, subserosa and serosa. Forty-eight percent of the patients had venous infiltration by the adenocarcinoma, while 60% had tumours that exhibited perineural invasion. Approximately 20% of patient specimens had Helicobacter pylori. While few (3.8%) patients were found to have chronic active gastritis, about 40% of them had chronic gastritis and about 30% had chronic multifocal atrophic gastritis (Table 3).

| Gross appearance | Percentage | |

| Configuration | Ulcerative | 56.00 |

| Infiltrative | 22.70 | |

| Exophytic | 21.30 | |

| n | 75 | |

| Gross location | ||

| Proximal | Uninvolved | 88.20 |

| Involved | 11.80 | |

| n | 76 | |

| Distal | Uninvolved | 84.20 |

| Involved | 15.80 | |

| n | 76 | |

| Histological appearance | ||

| Intestinal | No | 42.60 |

| Yes | 57.40 | |

| n | 68 | |

| Differentiation | Poor | 43.40 |

| Moderate | 50.90 | |

| Well | 5.70 | |

| n | 53 | |

| Grade | Low | 43.20 |

| Moderate | 32.40 | |

| High | 24.30 | |

| Maximum extent of invasion through stomach wall | ||

| Mucosa | Involved | 100.00 |

| n | 78 | |

| Muscularis propria | Uninvolved | 3.80 |

| Involved | 96.20 | |

| n | 78 | |

| Sub–Serosa | Uninvolved | 9.00 |

| Involved | 91.00 | |

| n | 78 | |

| Serosa | Uninvolved | 13.30 |

| Involved | 86.70 | |

| Histological appearance | ||

| Venous infiltration | Absent | 51.90 |

| Present | 48.10 | |

| n | 52 | |

| Perineural infiltration | Absent | 40.00 |

| Present | 60.00 | |

| n | 35 | |

| H. Pylori | Absent | 80.50 |

| Present | 19.50 | |

| n | 77 | |

| Chronic active gastritis | Absent | 96.20 |

| Present | 3.80 | |

| n | 78 | |

| Chronic gastritis | Absent | 59.00 |

| Present | 41.00 | |

| n | 78 | |

| Chronic multifocal Atrophic gastritis | Absent | 70.50 |

| Present | 29.50 | |

| n | 78 | |

There was a trend toward significance (P = 0.0577) in the lower survivorship of patients who had tumours of the gastric cardia vs those who did not. Patients who had a circumferential tumour had significantly worse survival times from those who did not have a circumferential tumour (P = 0.0370). There was also a near significant difference between patients with subserosal involvement vs those without (P = 0.0731). Patients who had serosal involvement of tumour did have a shorter survival than those who did not (P = 0.017) (Table 4). Patients who had venous infiltration also had shorter survival (P = 0.055) (Table 5). Differences for subserosal and serosal involvement could not be quantified as there were no deaths among patients who were negative. Differences in HRs were estimated for tumours of the gastric cardia, circumferential lesions and those with venous infiltration. Figure 1 show the survival curves for the aforementioned variables.

| Variable | P value |

| Gender | 0.9688 |

| Number of gastrectomies previously performed | 0.6725 |

| Lesser curvature | 0.9716 |

| Greater curvature | 0.7928 |

| Antrum | 0.2613 |

| Pylorus | 0.2486 |

| Body | 0.2581 |

| Cardia | 0.0577 |

| Fundus | 0.9704 |

| Anterior wall | 0.3977 |

| Posterior wall | 0.9507 |

| Circumferential | 0.0370 |

| Diffuse | 0.9389 |

| Intestinal | 0.6020 |

| Grade | 0.2436 |

| Configuration | 0.2598 |

| Differentiation | 0.2416 |

| Predictor | HR | P value | 95%CI | |

| Cardia | ||||

| Involved vs uninvolved | 2.685 | 0.069 | 0.927 | 7.779 |

| Circumferential | ||||

| Involved vs uninvolved | 2.424 | 0.044 | 1.025 | 5.732 |

| Venous infiltration | ||||

| Present vs absent | 2.502 | 0.055 | 0.98 | 6.384 |

| Age | 1.007 | 0.643 | 0.978 | 1.037 |

| Size | 0.992 | 0.897 | 0.877 | 1.122 |

| Positive lymph nodes | 1.059 | 0.118 | 0.986 | 1.137 |

| Total lymph nodes removed | 0.981 | 0.603 | 0.911 | 1.055 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Total gastrectomy vs subtotal gastrectomy | 1.45 | 0.417 | 0.591 | 3.553 |

| Presence of Helicobacter pylori | 0.456 | 0.198 | 0.138 | 1.508 |

The Kaplan-Meier estimated 10-year survival rate of this cohort is 42.1%, with a 95% confidence interval of 24.4%-58.7%. This Kaplan-Meier estimate accounts for the varying risks within the population with respect to their clinicopathological factors. This is appropriate as we have noted statistically significant impact of certain parameters on patient survival. If it were assumed that each patient was at an equivalent risk for mortality following surgery the incidental survival rate would be 35%. The median survival time was about 70 mo. These statistics reflect patients’ median follow up time and not a true median survival. Patients were followed for a total of 1912.115 person months during which time there were 30 deaths. This yields an estimated death rate of 0.0157 deaths per person-month, or 18.8% per person-year (95%CI: 0.132-0.269). This means that if we observed 100 persons with the disease for 1 year we would expect approximately 19 of them to die.

It is noted that the results were mostly negative, that is many tumour characteristics did not indicate any evidence of affecting patient survival. Table 3 shows the results of a power analysis to determine the power of our study to detect varying hazard rates. We see that, at best, the current sample with 30 observed events (deaths) would have about 30% power to detect a HR of 2.5. It is likely that the ability of this study to demonstrate pathological prognosticators already commonly accepted in the literature was limited by this relatively low power. We see that we could detect a hazard rate of 2 with power 80%, if we observed 202 deaths. As the examined cohort continues to grow yearly we can expect more robust statistics in future analyses. Furthermore, this study included all cause mortality. As the cohort continues to grow, exact causes of death can be better examined and adjusted for according to their likely direct relation to gastric cancer and therapeutic intervention for this disease process.

Age, size of tumour, number of positive nodes found and total number of lymph nodes removed were not useful predictors of survival. However, it was noted that patients who had a circumferential tumour were almost two and a half times more likely to die than those without. There was a similar increase in the likelihood of death for patients with tumours of the cardia, as well as in those with venous infiltration (Table 3).

In a previous clinicopathological audit of gastric carcinomas at this institution between 1993-2002, the majority of tumours (56%) were of the antrum. The cardia was the third most involved site at 7.9%[4]. The current study, 2000-2010, noted 9.1% of cases to involve the gastric cardia and 54.5% involving the antrum. While the majority of gastric cancers in our population continue to be found in the antrum, it is worth noting the increased incidence of cancers of the cardia. This early trend parallels the 29.0% to 52.2% increase in incidence of adenocarcinomas of the gastric cardia noted in the United Kingdom from 1984 to 1993[8]. Similarly the incidence of cardiac lesions increased from 29% to 52%, in the United States of America, between 1984-1993[9]. McLoughlin purports a generally poorer prognosis associated with cancers of the gastric cardia as opposed to other anatomical sites[10]. This prognosis is likely a consequence of more extensive lymphatic drainage of the region, and later diagnosis[10,11]. In this study a HR of 2.685 (P = 0.069) reflected, although not significantly, this increased risk of mortality. Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrate the decreased survivorship of cardiac gastric cancers in this Jamaican cohort. Finally, the Logrank test trended toward significance with a P value of 0.0577.

This study made evident a significant HR of 2.424 (P = 0.044) for patients with circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement post-gastrectomy. Logrank survival tests reflect this decreased survivorship with a P value of 0.0370. This applies to cancers of the cardia with extension into the distal oesophagus. CRM involvement has been shown to be an important prognostication factor for oesophageal cancer. Several studies have shown a poor prognosis in patients with potentially resectable malignancies of the distal 5 cm of the oesophagus and Siewert I adenocarcinomas of the gastro-oesophageal junction[12,13]. It would appear that the findings of our study reflect such trends.

As, both globally and locally, more proximal gastric tumour sites become increasingly prevalent, it is important to note the relatively poor outcomes of such cases post gastrectomy. As alluded to above, lymphatic drainage is thought to be a key contributor to such poor outcomes. Accordingly it is prudent to examine the approach to lymph node dissection and excision employed locally, as well as the correlation between lymph node positivity and survivorship. Our study did not demonstrate any significant influence of either lymph node positivity or total number of nodes resected on survivorship. However, Shimada et al[14] (2001) with a much larger cohort (982) concluded that the involvement of three or more metastatic lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor with a sharp decrease in 5-year survivorship of patients with greater than two nodes. An Italian randomised trial involving 615 gastric cancer patients demonstrated significant decrease in all-cause mortality varying proportionately with number of lymph nodes removed up to 25. The authors suggest a minimum of 25 nodes be removed for better long term survivorship[15]. Our study saw an average of only 8 nodes being removed. During this time at our institution the standard procedure performed was that of D1 gastrectomy. This was due to lack of personnel trained in D2 gastrectomy technique. The American Joint Committee on Cancer recommends a minimum of 15 lymph nodes be examined for accurate staging of gastric cancer as retrieved by D2 lymphadenectomy[16]. Only 4 of the 79 specimens reviewed met this recommendation, as D1 gastrectomies were performed. Interestingly, Schoenleber et al[17] suggest that the single most influential factor in optimising the number of lymph nodes retrieved, and consequently the number of positive lymph nodes identified from a gastric specimen, is the technique of the pathology technician in trimming the gross specimen. Thus, the relatively low yield of lymph nodes from the surgical specimens in this study may be a function of either surgeon skill or the technical ability of the pathologist trimming the specimen.

It is important to note that meta-analyses of D1 vs D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer have failed to demonstrate any survival benefit of extended resection[18]. The reason for this may be the increased surgical morbidity and mortality that is expected when less experienced staff perform the more technically complex D2 resection classically inclusive of splenectomy and pancreatectomy. At our institution 38% of the reviewed cases had been done by a surgeon who had previously performed less than 10 gastrectomies. No significant change in survivorship was attributable to surgeon experience. The ideal answer to balancing the risk of increased operative morbidity, against the need for oncological clearance of involved nodes, would be to identify involved nodes preoperatively. Currently, algorithms utilising prognostic factors such as age, sex, Borrmann classification and histology are being developed to do just that. The Maruyama computer program was used retrospectively to predict lymph node involvement by level and the results compared to actual pathological specimen findings. The prediction rate was highly accurate (82%-96%)[19]. This high predictive accuracy has been reproduced[20].

This study has also demonstrated an almost significant HR of 2.5 with regard to the survivorship of patients with tumours featuring venous infiltration (P = 0.055). A retrospective analysis, done in China, of 487 gastric cancer patients showed that lymphatic or blood vessel invasion in the presence of metastatic lymph node disease significantly decreased survivorship post gastrectomy[21]. In our study, all but two of the histological specimens had positive nodes, therefore a similar overall trend was observed. Additionally, a study, done in South Korea, of 280 node negative patients demonstrated significant worsened prognosis for patients with blood vessel invasion[22].

Given that there is sufficient evidence in the literature that some of these characteristics are clear indicators of survival, we could conclude that our study lacked the power to sufficiently detect the results. Specifically, a hazard rate of 2 with power of 80 would require 202 deaths to be observed and this would take about 30 years at our institution. This type of study would provide useful information for the Caribbean. We believe that it would be prudent to continue following this cohort of persons as well as enrolling new patients who are diagnosed with gastric cancer in order to better understand factors affecting survival in our population.

Of note, in this retrospective study we did not investigate the effect of chemotherapeutic interventions on survivorship. Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated the positive effect of such treatment on postoperative survival times of gastric cancer patients vs having just surgery[23].

Finally, modification of not only surgical but pathology staff practices may improve survivorship. Alteration of D2 gastrectomy to preserve pancreas and spleen has been shown to increase survival of stage three gastric cancer patients without any added risk of mortality or morbidity compared to D1 gastrectomy[24]. As previously mentioned, level of training of the pathology staff significantly affects the rate of retrieval of lymph nodes from surgical specimens. Education of relevant staff should be of benefit in that regard. Also, implementation of a surgical protocol ensuring AJCC recommendations, such as appropriate lymph node dissection, are followed, may improve specimen yield and thus diagnostic relevance. Epidemiological mapping of gastric cancer in the Afro-Caribbean population is of worldwide significance as, interestingly, relative rates of gastric cancer by ethnicity in England have been shown to be higher in black persons of Caribbean heritage[25].

Gastric adenocarcinoma is the most common type of cancer occurring the stomach. Despite robust clinical research, predominantly out of Japan, it remains a leading cause of cancer death both worldwide and in Jamaica. Before therapeutic strategies can be devised to reduce this burden in Jamaica, it is important to thoroughly describe both the pathological patterns seen here and the efficaciousness of current surgical management.

D2 gastrectomy, especially as performed by well practiced experts, has been shown to improve patient survivorship. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy is gaining international acceptance as beneficial to survival following the MAGIC trial. The use of software, such as the Maruyama computer program, has shown reproducible and accurate retrospective prediction of lymph node involvement by level. This is a potential means of minimising perioperative morbidity and mortality, by obviating unnecessarily extensive lymph node dissection during gastrectomy.

In Asia, Europe and North America clinicopathological factors such as tumour size, lymph node metastases, vascular and serosal invasion have been demonstrated as significant factors affecting patient prognosis. In addition a trend has been noted of increased incidence of more proximal anatomic location of these tumours in the stomach. This study sought to see whether these findings were similar in a Caribbean population.

The findings of this study will be used to refine and standardise lymphadenectomy technique at the institution and in the region. This is the first study of its kind from the Caribbean region which differs significantly in racial composition, dietary practice and resource availability from the regions of origin of most published data.

D1 gastrectomy–surgical resection of the stomach plus dissection of all group one or perigastric lymph nodes (left cardia, right cardia, lesser curve, greater curve, suprapyloric, infrapyloric); D2 gastrectomy–surgical resection of the stomach plus dissection of all perigastric lymph nodes plus those about the hepatic, left gastric, celiac, and splenic arteries, as well as those in the splenic hilum.

It has been well written and presents the valid issues regarding association of various factors with the survival of gastric cancer patients.

P- Reviewers: Shi C, Thakur B S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25541] [Article Influence: 1824.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Gibson TN, Hanchard B, Waugh N, McNaughton D. Age-specific incidence of cancer in Kingston and St. Andrew, Jamaica, 2003-2007. West Indian Med J. 2010;59:456-464. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Blake G, Hanchard B, Mitchell K, Simpson D, Waugh N, Wolff C, Samuels E. Jamaica cancer mortality statistics, 1999. West Indian Med J. 2002;51:64-67. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Plummer JM, Gibson TN, McFarlane ME, Hanchard B, Martin A, McDonald AH. Clinicopathologic profile of gastric carcinomas at the University Hospital of the West Indies. West Indian Med J. 2005;54:364-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Puri KS, Suresh KR, Gogtay NJ, Thatte UM. Declaration of Helsinki, 2008: implications for stakeholders in research. J Postgrad Med. 2009;55:131-134. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Wiley-Interscience. 2002;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Klein J P, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis. Wikipedia: Springer 2003; . |

| 8. | Wayman J, Forman D, Griffin SM. Monitoring the changing pattern of esophago-gastric cancer: data from a UK regional cancer registry. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:943-949. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Corley DA, Buffler PA. Oesophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinomas: analysis of regional variation using the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents database. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1415-1425. [PubMed] |

| 10. | McLoughlin JM. Adenocarcinoma of the stomach: a review. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2004;17:391-399. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Aikou T, Natugoe S, Tenabe G, Baba M, Shimazu H. Lymph drainage originating from the lower esophagus and gastric cardia as measured by radioisotope uptake in the regional lymph nodes following lymphoscintigraphy. Lymphology. 1987;20:145-151. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Scheepers JJ, van der Peet DL, Veenhof AA, Cuesta MA. Influence of circumferential resection margin on prognosis in distal esophageal and gastroesophageal cancer approached through the transhiatal route. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dexter SP, Sue-Ling H, McMahon MJ, Quirke P, Mapstone N, Martin IG. Circumferential resection margin involvement: an independent predictor of survival following surgery for oesophageal cancer. Gut. 2001;48:667-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shimada S, Yagi Y, Honmyo U, Shiomori K, Yoshida N, Ogawa M. Involvement of three or more lymph nodes predicts poor prognosis in submucosal gastric carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Marubini E, Bozzetti F, Miceli R, Bonfanti G, Gennari L. Lymphadenectomy in gastric cancer: prognostic role and therapeutic implications. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:406-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dikken JL, van de Velde CJ, Gönen M, Verheij M, Brennan MF, Coit DG. The New American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer staging system for adenocarcinoma of the stomach: increased complexity without clear improvement in predictive accuracy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2443-2451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schoenleber SJ, Schnelldorfer T, Wood CM, Qin R, Sarr MG, Donohue JH. Factors influencing lymph node recovery from the operative specimen after gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1233-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Memon MA, Subramanya MS, Khan S, Hossain MB, Osland E, Memon B. Meta-analysis of D1 versus D2 gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2011;253:900-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bollschweiler E, Boettcher K, Hoelscher AH, Sasako M, Kinoshita T, Maruyama K, Siewert JR. Preoperative assessment of lymph node metastases in patients with gastric cancer: evaluation of the Maruyama computer program. Br J Surg. 1992;79:156-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Guadagni S, de Manzoni G, Catarci M, Valenti M, Amicucci G, De Bernardinis G, Cordiano C, Carboni M, Maruyama K. Evaluation of the Maruyama computer program accuracy for preoperative estimation of lymph node metastases from gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24:1550-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Du CY, Chen JG, Zhou Y, Zhao GF, Fu H, Zhou XK, Shi YQ. Impact of lymphatic and/or blood vessel invasion in stage II gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3610-3616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hyung WJ, Lee JH, Choi SH, Min JS, Noh SH. Prognostic impact of lymphatic and/or blood vessel invasion in patients with node-negative advanced gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:562-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4899] [Cited by in RCA: 4608] [Article Influence: 242.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Edwards P, Blackshaw GR, Lewis WG, Barry JD, Allison MC, Jones DR. Prospective comparison of D1 vs modified D2 gastrectomy for carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1888-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Coupland VH, Lagergren J, Konfortion J, Allum W, Mendall MA, Hardwick RH, Linklater KM, Møller H, Jack RH. Ethnicity in relation to incidence of oesophageal and gastric cancer in England. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1908-1914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |