INTRODUCTION

Tuberculous gastric perforation is a rare presentation of gastric tuberculosis (TB) with six previous cases reported in the literature[1,2]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports of gastric perforation due to multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). Tuberculous bronchoesophageal fistula (TBEF) is also a very infrequent complication of extrapulmonary TB[3]. Although MDR-TB with TBEF has been reported in two cases, one case was in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive patient[4], and the other case was published in the Japanese language[5]. Moreover, these were cases of TBEF in patients with esophageal TB, but our case involved TBEF and gastric perforation in a patient with TB throughout the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The patient with severe pulmonary TB, especially combined extrapulmonary TB, can present with various complications, such as the need for surgery[6].

This report describes the first reported case of pulmonary TB with TBEF and gastric perforation caused by an MDR-TB strain in a non-acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patient.

CASE REPORT

A 53-year-old man was referred for evaluation of dysphagia of 1 mo duration. Two weeks prior to the referral, he had been admitted to a local hospital due to general weakness with mild odynophagia. He was diagnosed with pulmonary TB by a positive acid fast bacilli (AFB) smear, and anti-TB medication (isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide) was started in the local hospital. However, 3 d after the initiation of anti-TB treatment, he had a sudden onset of dysphagia even for liquids. He had a history of pulmonary TB that was diagnosed 12 years prior to presentation and was cured after 6 mo of anti-TB medication. He was an active smoker with a 30 pack-year smoking history, and he was an alcoholic. He had consumed 3-5 bottles of spirits (it is called “Soju” in Korea) and several bottles of beer every day for several years. The patient was hemodynamically stable. He had lost approximately 12 kg over the course of the previous year, 5 kg of which was lost in the month prior to presentation [170 cm, 43 kg, body mass index (BMI) of 14.9 kg/m2]. He complained of anorexia, nausea, odynodysphagia, and night sweats. On examination, he appeared cachectic, and lung auscultation revealed coarse breath sounds in the left upper lung field. There was no abdominal tenderness.

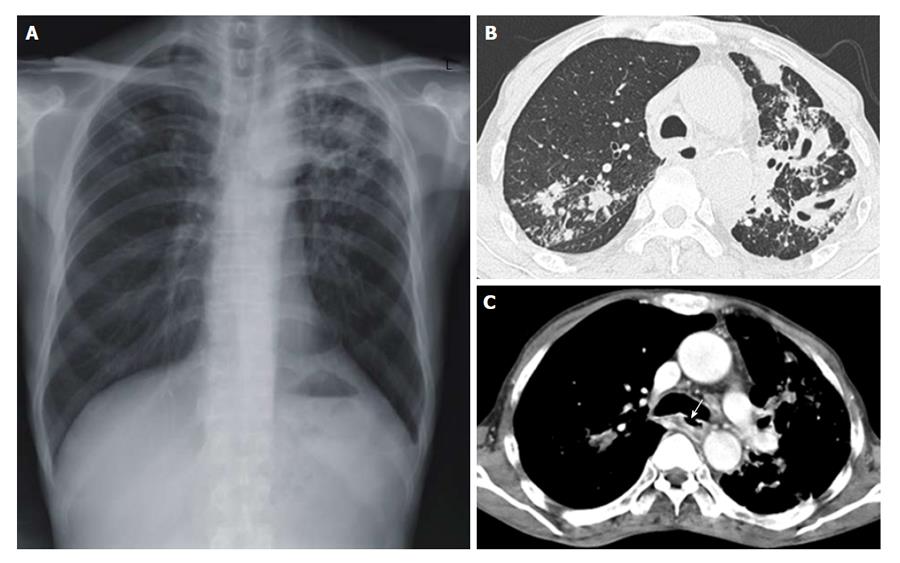

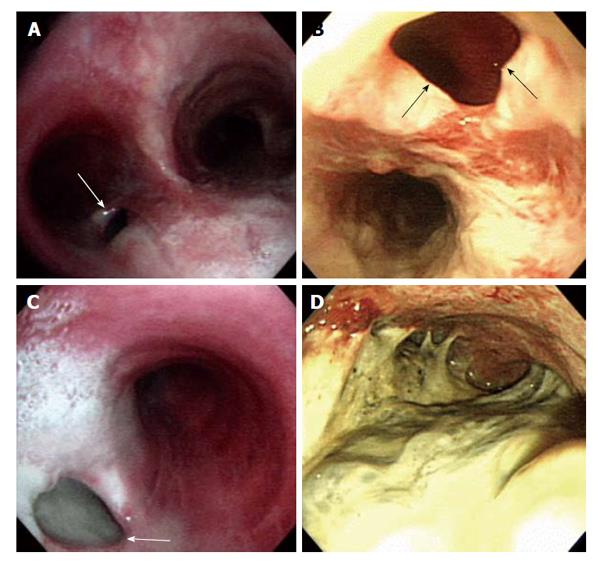

Laboratory data included the following: hemoglobin 157 (normal 140-180 g/L); white blood cell 8.5 (normal 4-10 × 106/L) (segmented neutrophils 73.8%, lymphocytes 16.2%); erythrocyte sedimentation rate 42 (normal < 15 mm/h); C-reactive protein 70 (normal < 0.5 mg/L); albumin 34 (normal 35-50 g/L); aspartate aminotransferase 42 (normal < 50 IU/L); alanine aminotransferase 30 (normal < 50 IU/L); alkaline phosphatase 136 (normal < 100 IU/L); amylase 203 (normal < 104 IU/L); lipase 46 (normal < 50 IU/L); and gamma-glutamyl transferase 185 (normal < 50 IU/L). HIV antibody was negative. Results of other biochemical tests were unremarkable. Staining of sputum for AFB was positive and Mycobacterium tuberculosis was cultured 1 mo later. Chest radiography at admission demonstrated combined reticulonodular densities and air space and nodular consolidation in both upper lobes, suggesting reactivated pulmonary TB (Figure 1A). Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple cavitary nodules with centrilobular nodules in both upper lobes (Figure 1B), a 1 cm-sized bronchoesophageal fistula (BEF) (Figure 1C) 11 cm below the thyroid cartilage, and diffuse esophageal wall thickening at the mid to lower esophagus. Additionally, lymphadenopathy was seen in the left upper paratracheal region, aortopulmonary window, and right hilar space. Bronchoscopy revealed whitish exudates over the whole trachea and a 1.5 cm hole at the inferior aspect of the left main bronchus orifice (Figure 2A and C). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) disclosed severe inflammation, ulceration, fibrotic scarring, easy touch bleeding throughout the entire esophagus, a fistula 28 cm from the incisors (Figure 2B), and severely inflamed gastric mucosa. The duodenum could not be observed due to pyloric deformity and exudates (Figure 2D). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis with an endoscopically biopsied specimen of the stomach was positive.

Figure 1 Chest radiograph and chest computed tomography scans are suggested reactivated pulmonary tuberculosis.

A: Chest radiograph revealing combined reticulonodular densities, air space and nodular consolidation in the both upper lobe of the lung; B: Chest computed tomography showing multiple cavities with centrilobular nodules in the left upper lobe of the lung; C: A 1 cm sized bronchoesophageal fistula (white arrow) was observed in the inferior wall aspect of the left main bronchus.

Figure 2 Bronchoscopy (A and C) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (B and D) show tuberculous bronchoesophageal fistula and nearby lesions.

A: A 1.0 cm × 1.5 cm sized hole (white arrow) was seen at the inferior wall aspect of the left main bronchus; B: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showing a large fistula (black arrows) was noted at the level of incisor 28 cm below; C: The lumen of fistula (white arrow) was filled up with whitish exudate secretion and materials; D: Edematous and hyperemic inflammatory mucosal changes with exudate materials were observed at whole stomach.

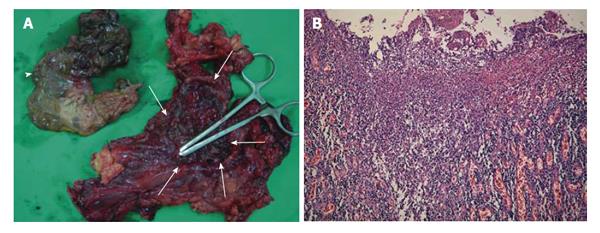

After admission, because the patient could not take the pills per os and failed insertion of a nasogastric tube, four parenteral anti-TB drugs (isoniazid 300 mg, rifampin 450 mg, streptomycin 0.75 g, and moxifloxacin 400 mg) with vitamin B6 and parenteral nutrition were given intravenously. After treatment, his intermittent fever subsided and his TB was considered to be improving. Symptomatic improvement was noticed but dysphagia for liquids persisted. However, on the 20th day, the patient complained of abdominal pain. On physical examination, his temperature was 38 °C and he felt chilly. Bowel sounds were absent and his abdomen was rigid with muscle guarding. The patient was ultimately diagnosed with pan peritonitis due to spontaneous perforation of the stomach. An emergency operation was performed. Nearly the entire greater curvature of the stomach was perforated due to severe ulceration. Gelatinous dirty exudative materials, similar to cysts, were seen on the side of the perforated stomach. Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y end-to-side esophagojejunostomy and feeding jejunostomy were successfully performed. Because the gastroesophageal junction was severely narrowed due to fibrotic change, esophagojejunostomy was performed according to the manual without a stapling device. The surgical specimen demonstrated diffuse transmural inflammation with extensive ulceration of the stomach and duodenum (Figure 3A and B). The patient was treated with injection of anti-TB medications for 46 d, and after the operation, the patient was also treated with medication (isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide) via jejunostomy for 41 d. The result of drug sensitivity testing (DST) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis showed MDR-TB (resistant to isoniazid: 1+ of 0.2 μg/mL; rifampin: 1+ of 1 μg/mL; ethambutol: 1+ for 5 μg/mL and susceptible of 10 μg/mL); therefore, the medications were changed to second line anti-TB drugs (para-aminosalicylic acid, streptomycin, and moxifloxacin) and susceptible first-line drugs (pyrazinamide and ethambutol). After 22 mo, he underwent esophageal reconstruction in our hospital with colonic interposition and jejunocolostomy using a 25-mm end-to-end anastomotic stapler. In surgical findings, we could not find the bronchoesophageal fistula, and whole esophagus had shrinkage and fibrotic changes because of severe inflammation. We think the fistula was healed by anti-TB medications and severe inflammatory changes around the esophagus. So we decided to perform a thoracic esophagectomy and colon interposition. Since then, he has been able to eat through his mouth.

Figure 3 Gross anatomic specimen and its macroscopic histology show severe tuberculous inflammation and necrosis from the totally resected stomach and a part of duodenum.

A: A huge defect (white arrows) in the gastric wall along the midbody and fundus. The dirty ragged tissue (white arrowhead) which was covering the defect was identified to be the infracted gastric wall pathologically; B: Histologic findings of the resected specimen in hematoxylin and eosin staining (original magnification × 100) showing diffuse transmural inflammation with extensive multiple ulcers on the stomach.

Although his body weight was 43 kg at the first referral time, he has gained weight up to 58 kg (BMI 20.1 kg/m2) at that time of decision for esophageal surgery after feeding through jejunostomy and appropriate anti-TB medications. But he has complained of not being able to eat. He hoped that he could eat through his mouth after the operation. After esophageal reconstruction operation, expectedly, he suffered from dumping syndrome such as diarrhea, light-headedness and sweating after meals. But he tolerated these symptoms gradually after food intake training for preventing dumping syndrome. One month after esophageal reconstruction surgery, he was discharged with his body weight at 53.7 kg. Two months later, he was readmitted to the hospital with a three-day history of abdominal pain and nausea. Esophagography showed severe stricture at colojejunostomy. He underwent a balloon dilatation procedure using a diameter 20 mm balloon successfully. After that time, he is able to eat again and be allowed to go home. Though he lost weight, his body weight was maintained at 51 kg within 6 mo after oral food intake.

DISCUSSION

MDR-TB is defined as a strain of TB with documented resistance in vitro to at least isoniazid and rifampin. The global population weighted proportion of MDR-TB among all TB cases is 5.3% with an estimated 0.5 million cases[7]. The incidence of MDR-TB has continuously increased in Korea. According to a 2007 report[8], the prevalence of MDR-TB increased from 1.6% to 2.7% of all TB cases between 1994 and 2004. There was a particularly high increase in the 30-39 age group, with the incidence of MDR-TB in retreatment patients reaching 21.4%. Additionally, some countries are showing increases in MDR-TB with rates as high as 22.3% among new cases and 60.0% among previously treated cases[7].

Extrapulmonary TB occurs in 70% of AIDS patients compared with 20% of non-AIDS related TB cases[9]. GI TB is presently nearly the sixth most common site of extrapulmonary TB, similar to the incidence of peritoneal TB, in the United States[10]. But esophageal TB is rare among GI TB because exposure of the esophagus to the organism is limited by the rapid clearance of infected sputum by means of coordinated peristalsis combined with upright posture and an intact lower esophageal sphincter[11]. Esophageal TB may present with dysphagia and may be complicated by ulcer or stricture formation, perforation, and fistulae[12]. Upper GI endoscopy is the most useful tool in establishing the diagnosis, particularly with biopsy of the affected area[13]. In addition, chest CT may be useful in identifying the presence of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and fistula, as in our case. It is well established that AFB staining for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is positive in less than 25% cases[14]. Therefore, Abid et al[15] suggested that certain endoscopic features, such as deep and large esophageal ulcers and tracheoesophageal fistula, are strongly suggestive of TB-related lesions.

As Lado Lado et al[3] have reviewed, only 36 cases of TBEF were reported between 1893 and 2001. The development of TBEF could be due to the following mechanisms: rupture of caseonecrotic subcarinal lymph nodes into the esophagus and trachea; development of traction diverticula between the respiratory tree and the esophagus; or erosion of primary tracheal ulcers into the esophagus[16]. The most common symptoms of BEF are chronic and paroxysmal cough, dysphagia, fever and pneumonia[3]. Ono’s sign is pathognomonic of BEF; it includes paroxysmal cough on ingestion of liquids and crepitation posteriorly over the sixth right intercostal space (cited in Alkhuja et al[17]). But our patient did not exhibit Ono’s sign initially. He had complaints of mild odynophagia without paroxysmal cough that was simultaneous with oral ingestion of food. Three days after starting anti-TB mediation, he had the sudden onset of the inability to swallow even water.

On EGD, we found severe inflammation and easy touch bleeding from the esophageal orifice to the stomach with esophageal fistula. This sudden onset of aggravated symptoms may represent a paradoxical response. Cheng et al[18] reviewed 122 episodes of paradoxical responses after anti-TB medication in non-HIV infected patients. Overall, 82.8% were associated with extrapulmonary TB and 95% of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates were susceptible to first-line anti-TB therapy. Esophagography is highly helpful in visualizing the fistula[17]. However, we did not perform esophagography because the patient could not swallow. The role of bronchoscopy is diagnostic to visualize proximally located TBEF and to obtain specimens[4]. The reported overall yield of bronchoscopy in detecting TBEF is as high as 83%[19]. In addition to this diagnostic role, bronchoscopy performed in conjunction with esophagoscopy allows preoperative analysis and planning for surgical correction[20]. Though traditionally the treatment of TBEF has relied on surgery[16], recent therapies have favored medication, which has proven to be successful in anti-TB treatment[3]. However, our patient could not be treated by medication only and he ultimately underwent an esophageal reconstruction operation. Treatment for MDR-TB requires second-line drugs that are less effective. Multidrug regimens consist of a minimum of four or five drugs to which the infecting strain has documented susceptibility and the regimen should be used for a minimum of 18 to 24 mo[21]. Our patient received five drugs to which his MDT-TB was susceptible for 18 mo after DST.

The stomach is the sixth most common site in the GI tract to be affected by TB, following the ileocecal region, ascending colon, jejunum, appendix, and duodenum[22]. Possible causes for stomach sparing include high acidity, a paucity of lymphoid tissue, and rapid transit of food in the stomach[10]. Therefore, long-term therapy with H2 blockers increases the incidence of gastric TB due to decreased acidity[23]. The gross appearance of gastric TB has been described, and it is generally divided into three categories: tuberculous, ulcerative, and hypertrophic[24]. Definitive diagnosis of gastric TB requires the identification of AFB in biopsy material or microbial culture, which is not always possible. In the absence of AFB, the presence of a caseating granuloma may be considered diagnostic[22]. Our patient had severely inflamed gastric mucosa on EGD, and the PCR of the gastric biopsy specimen was positive. Gastric TB presents most commonly as an ulcer with or without associated gastric outlet obstruction. This kind of presentation is seen in approximately 80% of cases, with ulcers ranging from a few millimeters to as large as 20 cm, and manifests as non-specific chronic abdominal pain[22].

Tubercular gastric ulcers usually perforate or bleed because of their superficial location and associated endarteritis[1]. Patients with complications, such as pyloric mass, stenosis, bleeding, or perforation, require surgery[1]. Treatment with anti-TB drugs should be followed by surgical intervention[24].

In conclusion, this is the first reported case of successfully treated upper GI TB with TBEF and gastric perforation caused by an MDR-TB strain in a non-AIDS patient. Although the incidence of MDR-TB is low in the West and developed countries, some countries are showing increases of MDR-TB among new cases and particularly among previously treated cases. The various manifestations observed in patients with TBEF, gastric perforation, or both suggest a need for careful monitoring and management including surgery and anti-TB medications based on adequate culture and DST.

P- Reviewer: Alvares-da-Silva MR S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ