Published online Jul 27, 2013. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i7.216

Revised: June 18, 2013

Accepted: June 28, 2013

Published online: July 27, 2013

Processing time: 219 Days and 15.1 Hours

AIM: To determine the morbidity and mortality associated with emergency laparotomy for a clinically acute abdomen in patients aged ≥ 80 years.

METHODS: In this retrospective audit, octogenarians undergoing emergency laparotomy between 1st January 2005 and 1st January 2010 were identified using the Galaxy Theatre System. Patients undergoing abdominal surgery through groin crease incisions or Lanz or Gridiron incisions were excluded. Also simple appendectomies were excluded. All patients were aged 80 years or more at the time of their surgery. Data were obtained using casenote review with a standardised proforma to determine patient age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, indications for surgery, early (within 30 d) and late (after 30 d) complications, mortality and length of stay. Data were inserted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analysed.

RESULTS: One hundred patients were identified from the database (Galaxy) as having undergone emergency laparotomy. Of those, 55 underwent the procedure for intestinal procedures and 37 for secondary peritonitis. There was a 2:1 female predominance; average age 85 and ASA grade 3. Bowel resection was required in 51 out of the 100 patients and 22 (43%) died. Other procedures included appendicectomy, adhesiolysis, repair of AAA graft leak and colostomies for the pathological process resulting in an acute abdomen. Twelve of 100 patients (12%) suffered intra-operative complications, including splenic and bowel-serosal tears. Seventy patients (70%) had postoperative complications including myocardial infarction, wound infection, haematoma and sepsis. Overall mortality was 45/100 patients (45%). The major causes of death were sepsis (19/45 patients, 42%), underlying cancer (13/45 patients, 29%); with others including bowel obstruction (2/45 patients, 4%), myocardial and intestinal ischaemia and dementia.

CONCLUSION: Emergency laparotomy in octogenarians carries a significant morbidity and mortality. In particular, surgery requiring bowel resection has higher mortality than without resection.

Core tip: Aging is associated with an increase in operative and anaesthetic risk during emergency laparotomy. Literature addressing the outcomes following emergency laparotomy in the elderly is limited. The morbidity and mortality rates in this subgroup of patients were explored, and in our study we determined the mortality rate to be 45%.

- Citation: Green G, Shaikh I, Fernandes R, Wegstapel H. Emergency laparotomy in octogenarians: A 5-year study of morbidity and mortality. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 5(7): 216-221

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v5/i7/216.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v5.i7.216

An aging United Kingdom population has lead to an increase in the number of emergency general surgical admissions in octogenarians; indeed 8739 patients over the age of 75 required emergency laparotomy in 2010-2011[1]. This has significantly increased from 4486 patients in 2001 reflecting the increased life expectancy of today’s population, with the average person living to 80 years compared with 74 years in 1983[2].

Laparotomy is a major intervention. Given that it is a considerable surgery to undertake it is not surprising that laparotomy is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, especially in the emergency setting, with current literature quoting mortality figures of 10%-55%[3-5].

Elderly patients present a higher risk for abdominal surgery owing to an increase in the number and severity of medical co-morbidities which may add to the complexity of both surgery and anaesthesia. The aging cardiovascular and immune systems predispose elderly patients to increased postoperative infection and cardiovascular events such as stroke, myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolism. Also older patients have a reduced physiological reserve to cope with longstanding hypotension secondary to anaesthesia and blood loss during surgery; and may take considerably longer to recuperate postoperatively although recent studies and scoring systems show that this is very subjective and that many older patients recover well postoperatively and return to function as well as their peers[6,7].

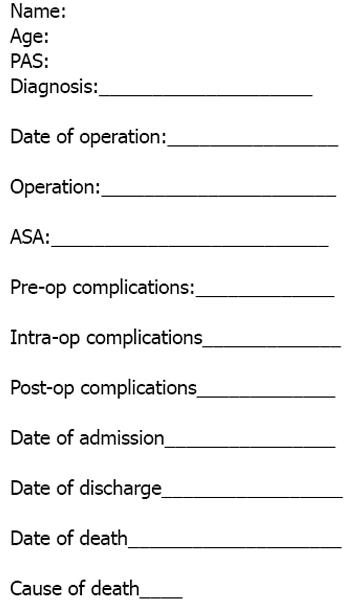

In this 5 year retrospective study, patients undergoing emergency laparotomy for intestinal conditions or secondary peritonitis between 1st January 2005 and 1st January 2010 were identified using the galaxy theatre management system used at Medway Maritime Hospital NHS trust (Galaxy Theatre System, Sanderson Ltd, 1-2 Venture Way, Aston Science Park, Birmingham, United Kingdom). Patients included in the study were those who were aged 80 years or over at the time of their operation. Laparoscopy alone without subsequent conversion to laparotomy and procedures involving inguinal incision for hernia repair were excluded from the study, as were other procedures such as simple appendicectomy if performed by Lanz incision. Medical records for the remaining relevant patients were sought and reviewed individually using the pro-forma shown in Figure 1. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade was determined from the anaesthetic pre-operative assessment chart and is shown in Table 1. Data was inserted into a spreadsheet and analysed using Microsoft Excel software.

| ASA grade | Description |

| I | Normal healthy patient |

| II | Mild systemic disease – no functional limitation |

| III | Severe systemic disease – definite functional limitation |

| IV | Severe systemic disease which is a constant threat to life |

| V | Moribund patient who is unlikely to survive > 24 h with or without surgery |

Overall, 100 patients underwent emergency laparotomy for abdominal pathology between 1st January 2005 and 1st January 2010. Eight additional patients were excluded from the study as these patients underwent laparoscopy, and local approaches for hernia repair rather than a midline laparotomy incision.

Data was collected from 100 patients who underwent emergency laparotomy between 1st January 2005 and 1st January 2010, all of whom were 80 years or over at the time of surgery. Overall, the mean age was 85 years (range 80-96 years); 2:1 female predominance and mean ASA grade of 3.08 (range 1-5).

The indications for surgery and their corresponding patient numbers are shown in Table 2. Thirty seven of 100 patients underwent laparotomy for secondary peritonitis; of which 14/37 had lower gastrointestinal (GI) perforation including perforated diverticulitis and perforated appendicitis; 16/37 had upper GI perforation including perforated gastric and duodenal ulcers; and the remaining 7/37 had perforation of unknown or undocumented site. Twenty of 37 patients died, of which 10/37 had a upper GI perforation, and 9/20 had lower GI perforation. There was no statistically significant difference in mortality by the site of perforation.

| Indication for surgery | Number of patients |

| Hernia | 12 |

| Secondary peritonitis | 37 |

| Colonic obstruction | 40 |

| Leaking colonic anastomosis | 1 |

| Aorto-bifemoral graft removal | 1 |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 1 |

| Bowel ischaemia | 5 |

| Pseudo-obstruction | 1 |

| Colo-vesical fistula | 1 |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | 1 |

Laparotomy to relieve colonic obstruction secondary to malignancy or adhesions was performed in 40/100 patients. The mortality in this group of patients was 17/40 patients (42.5%)

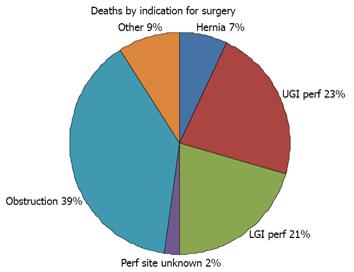

The mortality by indication for surgery is shown in Figure 2.

Bowel resection was required in 51/100, patients with the main indication being malignancy, or ischaemia of the bowel secondary to adhesions. Of the 51 patients requiring bowel resection, 23/51 died (mortality 45%). Thirty one of 51 patients required bowel resection secondary to obstruction, with a mortality of 13/31 (42%). Seventeen of 51 patients required bowel resection from the complications of GI perforation and secondary peritonitis. Of these patients, 14/17 had lower GI perforation (i.e., perforated diverticulitis) and 2/17 had upper GI perforation. No patients undergoing laparotomy for peptic ulcer perforation required resection. Nine of 17 patients with secondary peritonitis died, giving a mortality of 53%.

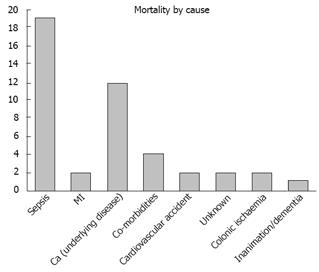

The overall mortality for emergency laparotomy in octogenarians in this study is 44/100 (44%). There is a 2:1 female predominance. Sepsis represented the most frequent cause of death (19/45 patients, 42%), closely followed by death due to the underlying disease process, chiefly colonic cancer (12/45 patients, 27%). Other causes were myocardial infarction (2/45 patients, 4%), cerebrovascular disease (2/45 patients, 4%), death due to medical co-morbidities such as exacerbation of chronic airways disease (4/45 patients, 8%). Two of 44 (4%) patients died due to ischaemic bowel postoperatively and 2/44 patients (4%) had an unknown cause of death. One further patient was deemed to have died of inanimation and dementia. Pictorial representation of mortality by cause of death is shown in Figure 3.

Sepsis represented 42% of the mortality. There were 2 sources of infection in these patients: 8/19 (42%) patients had abdominal sepsis and 8/19 (42%) had respiratory sepsis. The remaining 3/19 (16%) had sepsis of unknown origin.

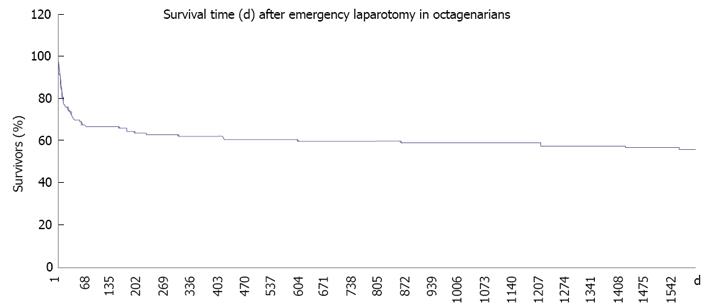

The survival curve shown in Figure 4 shows that procedure associated mortality occurs early, with 50% of deaths occurring within 2 wk of surgery. The majority of patients who leave hospital following laparotomy survive more than 30 d. Twelve of 44 (27%) patients died following discharge from hospital, all of these deaths were unrelated to the operation but to the underlying illness or to unrelated acute problems which occurred more than 1 year later.

Twelve of 100 patients (12%) suffered intra-operative complications, including splenic and bowel-serosal tears, and abandonment for futility. Seventy patients (70%) had postoperative complications including myocardial infarction (4/70, 5%), wound infection (6/70, 7.5%) and sepsis (32/70, 46%) which was largely of respiratory origin. Multi-organ failure occurred in 2 patients (2.5%). Other complications include cardiovascular problems including atrial fibrillation (AF) and congestive cardiac failure (8/70, 10%). The other causes of morbidity making up the remaining 39% included cardiovascular accident (CVA), scrotal oedema, stoma problems, rectal bleeding and acute renal failure.

On average emergency laparotomy costs £10000 per patient, giving a total surgical cost for our cohort of £100000. Added to this the average length of stay was 27 d (range 1-192 d). Our patients on average spent 3 d in critical care. The cost of a critical care stay for 3 d is £4200 and the cost per day for an national health service (NHS) bed is £400. So the average cost of an emergency laparotomy per patient assuming 27 d stay with 3 d critical care admission is £23800. This gives a total cost for our cohort of £238000. Forty four percent of these patients died (i.e., a loss of £104720) which limits the cost effectiveness of this procedure and highlights the importance of patient selection in terms of cost effectiveness and productivity.

A change in United Kingdom demographics has lead to an increasingly elderly population and prompted increased demand for acute surgical care in octogenarians[9]. The catchment population of Medway Maritime hospital is generally of low socioeconomic status[10], and patients tend to present to hospital late with extensive surgical disease and multiple medical and social co-morbidities. Given their poor physiological reserve for extensive surgery and anaesthesia, the decision to treat these patients operatively must be undertaken with extreme care and consideration; and must take into account the patient’s future quantity and quality of life and the health beliefs of patients and their relatives. Additionally in today’s age of austerity surgeons are also urged increasingly to consider cost implications of emergency surgery in patients with a potentially limited prognosis[11]. Thus the indications for surgery in this age group are often limited. Trends in management of elderly patients are inconsistent; previously there was a tendency towards conservative or palliative management of these patients, however with newer techniques and increased patient expectations these opinions are shifting towards increasingly operative intervention[12].

Studies have shown that the number of octogenarians requiring admission to acute surgical wards and ICU beds has been increasing. Reiss et al showed 7.5% of general surgical admissions in their series were aged 80 years or over, and more recently a 5 year study in Bath showed that 8.8% of admissions to intensive care unit (ICU) in 5 years were in elderly patients and a Turkish study done in 2002 showed 19% of cases in their series to be aged over 80 years[9,12,13].

Mortality rates in octogenarians have been documented as between 10% and 55%, with an increased risk in emergency as opposed to the elective setting[3]. We show a mortality rate for emergency laparotomy only of 44% which is in keeping with previous studies. There is limited literature documenting morbidity data in the group of patients in our study. We show a morbidity rate of 70% within 30 d of operation. Mortality and morbidity are often inextricably linked and therefore may lead to increased numbers seen. 25/44 patients who died had morbidity postoperatively, however 12 of these had complications completely unrelated to their abdominal pathology such as hypertensive episodes, exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and angina.

Surgical treatment of secondary peritonitis; which can be defined as the localized equivalent of the systemic inflammatory response within the peritoneal cavity secondary to contamination from another process for example bacteria from colonic perforation or chemical from pancreatic enzyme leakage, is documented to have a significant morbidity and mortality studies show there is a direct link between the age of the patient and the risk of severe sepsis[13-16]. We show that mortality is 53% in secondary peritonitis, which is not significantly higher than in obstructive indications for laparotomy. There is no significant difference in mortality if the location of the perforation is in the upper or lower GI tract.

Postoperative mortality in our study can be seen to occur most commonly within the first 2 wk and during the initial surgical admission. Death later following discharge is from unrelated causes such as acute MI or dementia, and therefore the immediate postoperative care of these patients is of high importance, as most patients who are discharged from hospital recuperate and there is a relatively low mortality following successful discharge.

A high preoperative ASA grade (3-5) of patients, suggesting significant medical co-morbidity preoperatively, was unsurprisingly seen to be associated with increased operative complications and a higher risk of perioperative death. Tan et al[17] demonstrated a similar conclusion in trauma patients from the Auckland registry, by showing that key comorbidites taken from the APACHE 2 score which include cirrhosis, severe heart failure (NYHA IV), severe COPD, dialysis patients and the immunosuppressed have an increased mortality regardless of age. In our cohort these patients are represented by those with ASA 5 (life threatening illness) and all of these patients died, regardless of their age. However survival and mortality rates were of a similar proportion of those of ASA grades 3 and 4, which still represent severe comorbidity, and the mean ages of those who survived and died were equal. This suggests comorbidity rather than age is important in predicting mortality and is in agreement with the findings in the aforementioned study.

The high incidence of sepsis postoperatively may demonstrate that elderly patients are at increased risk of infection due to an aging immune system, reduced physiological reserve, and high incidence of polypharmacy. Sepsis in our patients had either a urinary or respiratory source; which may reflect poor respiratory function postoperatively from an aging respiratory tract, poor analgesia and the increased use of catheters and urinary incontinence in this age group. It may also suggest poor hydration and nutrition in these frail patients, although this should be correlated with the admission and post-operative malnutrition universal screening tool scores, a tool developed by the British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition in order to assess patients nutritional status[18]. An objective study to determine quantitatively the effect of malnutrition on octagenarians undergoing emergency abdominal surgery may be an area for further study development.

Given the high risk nature of this group of patients, a multidisciplinary approach to care may be most appropriate in order to optimize patient care. This may involve elderly care physician input, dieticians, physiotherapists and occupational therapists alongside the general surgical team. This would allow optimisation of co-morbid conditions, optimize postoperative functioning and nutrition and allow prompt and safe discharge to an appropriate environment. This arrangement has already been established in orthopaedics in the care of elderly patients with femoral neck fractures and is well documented by the national hip fracture database[19]. These orthopaedic patients are essentially in a similar position to the patients in our study; they are elderly patients with acute surgical problems.

In a conclusion, emergency laparotomy is a procedure which is well recognized to carry significant intra- and postoperative risk; and one which is not undertaken lightly by surgeons. The decision to operate in octogenarian patients is difficult and requires careful consideration of the patient’s pre-morbid condition and counselling of both patients and relatives; thus highlighting the importance of patient selection[20]. It has been shown that the seniority of both the anaesthetist and operating surgeon influences mortality, hence elderly patients should receive consultant led anaesthetic and surgical care on an appropriate emergency list at a reasonable time of day[3]. Guidelines for the care of the elderly postoperative patient following extensive surgery are currently not routinely used and may be of significant use to medical and nursing staff untrained in elderly care, and therefore we recommend that these be put in place.

Ageing is associated with increases in operative and anaesthetic risk during emergency laparotomy. Literature concerning the outcomes following emergency laparotomy in the elderly is limited.

Many scoring systems exist to aid the surgeon and anaesthetist in determining preoperative risk, such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, POSSUM and APACHE scores but these are of limited use in older patients or in the emergency setting. The decision to manage operatively or conservatively is very important and poses many difficult ethical and moral problems. Future quality and quantity of life in patients, whether undergoing surgery or not, is subjective and unpredictable therefore preoperative counselling of patients and relatives is highly important

Emergency laparotomy is a topic of major concern to both surgeons and managers alike. The high complication risk may lead to longer hospital stays and prove a costly procedure for trusts. Current literature concerning patients over 80 years old and the outcomes following their surgery is lacking and therefore we undertook this project in order to fully evaluate this potentially dangerous subgroup of patients, and add to the current literature to guide clinical decision making.

Current literature is lacking for octogenarian patients, therefore this study was undertaken in order to guide healthcare professionals in the decision making process and management of elderly patients with acute abdominal surgical problems.

The topic was reviewed as being clinically relevant, and was comparative with previous literature as described in trauma patients.

P- Reviewer Mittal AS- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Hospital Episode Statistics 2010-2011 and 2000-2001. DoH publication. Available from: http: //www.hesonline.nhs.uk/. |

| 2. | Available from: http: //data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN/countries/1W-GB?page=6&display=default. |

| 3. | Cook TM, Day CJ. Hospital mortality after urgent and emergency laparotomy in patients aged 65 yr and over. Risk and prediction of risk using multiple logistic regression analysis. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:776-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Waldron RP, Donovan IA, Drumm J, Mottram SN, Tedman S. Emergency presentation and mortality from colorectal cancer in the elderly. Br J Surg. 1986;73:214-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ford PN, Thomas I, Cook TM, Whitley E, Peden CJ. Determinants of outcome in critically ill octogenarians after surgery: an observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:824-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Adkins RB, Scott HW. Surgical procedures in patients aged 90 years and older. South Med J. 1984;77:1357-1364. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Rix TE, Bates T. Pre-operative risk scores for the prediction of outcome in elderly people who require emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2007;2:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wolters U, Wolf T, Stützer H, Schröder T. ASA classification and perioperative variables as predictors of postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 742] [Cited by in RCA: 742] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Royal College of Surgeons of England Working Group. The Higher Risk General Surgical Patient: Towards Improved Care for a Forgotten Group. RCSENG-Professional Standards and Regulation. 2011;. |

| 10. | Available from: http: //neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/HTMLDocs/poverty.html. |

| 11. | Levinsky NG. Age as a criterion for rationing health care. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1813-1816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gürleyik G, Gürleyik E, Unalmişer S. Abdominal surgical emergency in the elderly. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2002;13:47-52. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Reiss R, Deutsch A, Nudelman I. Surgical problems in octogenarians: epidemiological analysis of 1,083 consecutive admissions. World J Surg. 1992;16:1017-1020; discussion 1017-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Maddaus MA, Ahrenholz D, Simmons RL. The biology of peritonitis and implications for treatment. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:431-443. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Anaya DA, Nathens AB. Risk factors for severe sepsis in secondary peritonitis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2003;4:355-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wittman DH, Schein M, Condon R. Management of secondary peritonitis. Ann Surg. 1996;224:10-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tan CP, Ng A, Civil I. Co-morbidities in trauma patients: common and significant. N Z Med J. 2004;117:U1044. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Henderson S, Moore N, Lee E, Witham MD. Do the malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST) and Birmingham nutrition risk (BNR) score predict mortality in older hospitalised patients? BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Available from: http: //www.nhfd.co.uk/003/hipfracturer.nsf/luMenuDefinitions/F29405CD131D1F36802579C900553994/$file/NHFD National Report 2011-Summary.pdf?. |

| 20. | Bufalari A, Ferri M, Cao P, Cirocchi R, Bisacchi R, Moggi L. Surgical Care in Octagenarians. BJS. 1996;83:1783-1787. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |