Published online May 27, 2013. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i5.156

Revised: March 20, 2013

Accepted: March 28, 2013

Published online: May 27, 2013

Processing time: 104 Days and 3 Hours

A 61-year-old male was admitted to our hospital due to right lower abdominal pain and watery diarrhea for 3 d. Beginning 3 wk before he arrived in our hospital, he took 3rd-generation cephalosporin (cefixime) for

2 wk due to chronic left ear otitis media. Colonoscopic examination revealed yellowish patches of ulcerations and swelling covered with thick serosanguineous exudate in the cecum and ascending colon. After 7 d of oral metronidazole treatment, his symptoms completely disappeared. We report a case of localized pseudomembranous colitis in the cecum and ascending colon mimicking acute appendicitis associated with cefixime.

Core tip: Pseudomembranous colitis is mostly related to antibiotics, and it presents symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, hypoalbuminemia and hypovolemia. Diarrhea is the most common manifestation, but in geriatric patients, symptoms of pseudomembranous colitis can be different from those of usual cases, and the disease course can be more aggressive. For these reasons, it can be misdiagnosed. Therefore, physicians must consider pseudomembranous colitis in older patients with acute abdominal pain who have been treated with antibiotics. We report a case of an older patient with pseudomembranous colitis that was misdiagnosed as acute appendicitis.

- Citation: Chyung JW, Shin DG. Localized pseudomembranous colitis in the cecum and ascending colon mimicking acute appendicitis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 5(5): 156-160

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v5/i5/156.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v5.i5.156

Patients who are administered antibiotics often experience diarrhea (referred to as antibiotic-associated diarrhea), and when these patients are proven to have inflammation in the colon, it is known as antibiotic-associated colitis. Furthermore, when patients with antibiotic-associated colitis have more inflammation in the colon and show pseudomembrane formation, it is referred to as pseudomembranous colitis.

Here, we present the case of a 61-year-old male patient who was first suspected of having acute appendicitis and had been experiencing right lower abdominal pain, tenesmus, and frequent watery diarrhea for 3 d before visiting the hospital. He also had a history of taking a cephalosporin antibiotic (cefixime) for 2 wk after an outpatient visit to the otolaryngology department to treat otitis media of the left ear 3 wk before visiting us. Based on these findings, we performed hematologic, colonoscopic, and histologic examinations and found pseudomembranous colitis limited to the cecum and the right ascending colon. We also present a literature review.

A 61-year-old male had right lower abdominal pain, frequent watery diarrhea. He was underwent antibiotic treatment for otitis media in the right ear 3 wk previously and had been taking diabetes medications for 19 years. He had no specific history.

Three weeks before visiting us, he was diagnosed with otitis media in the left ear and had been taking a 3rd-generation cephalosporin antibiotic (cefixime) prescribed by the otolaryngology department at our hospital for 2 wk. He stated that a week before the visit, he began to suffer from discomfort in the right lower abdomen, tenesmus, and intermittent and frequent watery diarrhea several times a day. When he made an outpatient visit to the department of surgery, he reported that he had not been able to tolerate the consistent right lower abdominal pain for the previous 3 d.

When he visited us, his vital signs were blood pressure 110/60 mmHg, pulse rate 80 bpm, respiratory rate 20/min, and body temperature 36 °C but without fever or chills. He presented a slightly decreased appetite, and based on the clinical manifestations found through his physical examination, his bowel sounds were normal. Although the right lower abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness were obvious, our digital exploration did not find any lump.

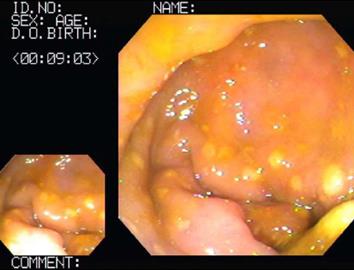

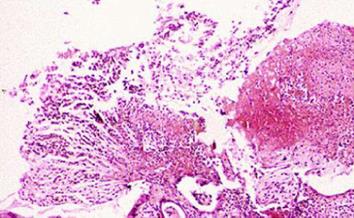

The hematological examination results were peripheral blood white blood cell count 8900/mm3, hemoglobin 15.3 g/dL, hematocrit 44%, platelet count 123 × 103/mm3, and CRP 15.2 mg/L. Meanwhile, his urinalysis results were normal, except for glucose (+++). His ultrasound results on the day of the visit showed that every layer of the serous membranes of the ascending colon and cecum was hypertrophic, whereas the serous membrane of the appendix was slightly hypertrophic, secondary to inflammatory responses in the colon (Figure 1). The results of an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan performed the day after the visit showed that the serous membranes of the cecum and ascending colon were generally hypertrophic, and there were inflammatory infiltrates around the colon (Figure 2). A colonoscopy performed on the 4th d also found pseudomembranous colitis limited to the cecum and ascending colon; thus, a biopsy was carried out (Figure 3). The biopsy confirmed that he had typical pseudomembranous colitis with crater-shaped ulcers (Figure 4), and the stool analysis showed that he was positive for Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) cytotoxin (0.09).

On the day that the biopsy confirmed pseudomembranous colitis, he began oral treatment with 250 mg of metronidazole 4 times a day. After 3 d, his defecation disorder and right lower abdominal pain mostly disappeared. In addition, when he was discharged, he was able to eat properly. He was orally administered metronidazole for 7 d, and through a colonoscopy performed a month after discharge, we were able to confirm that his intestinal mucosa had returned to normal (Figure 5).

Pseudomembranous colitis was first reported in 1893, and it was rare before antibiotics came into widespread use. In the early 1950s, as antibiotics began to be widely used, the incidence of pseudomembranous colitis also began to rise. At the time, people suspected that the main cause of pseudomembranous colitis was Staphylococcus aureus, one of the most common nosocomial infections. However, in 1974, a prospective study revealed that approximately 20% of patients who were administered clindamycin experienced antibiotic-associated diarrhea, and half of them suffered from pseudomembranous colitis.

In 1935, Hall and O’Toole claimed that C. difficile was a normal part of the flora of infants’ intestines. They described it as “the difficult clostridium” because an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus was considered the most difficult bacteria to grow in culture[1]. In an animal study, it was shown that C. difficile could secrete powerful toxins, but its clinical significance was discovered in the late 1970s. At that time, for the first time, C. difficile and its cytotoxin were found in the feces of almost every patient with pseudomembranous colitis but not in the feces of healthy people; this indicated that the toxins produced by C. difficile caused pseudomembranous colitis.

The first case of pseudomembranous colitis that occurred in the cecum and appendix was presented in 1997 by Coyne et al[2]. A 76-year-old female patient who was receiving hemodialysis for chronic renal failure experienced pseudomembranous colitis after being administered clindamycin to treat abdominal pain and diarrhea, but pseudomembranous colitis reoccurred a month after using metronidazole, and this led to her death. Based on the colonoscopy performed when she was admitted to the hospital, she was diagnosed with pseudomembranous colitis in her diverticulum, cecum, and appendix across her transverse colon and descending colon.

In approximately 90% of cases, C. difficile is found in the rectum and sigmoid colon on colonoscopy. However, in approximately 10% of cases, it occurs in the distal colon; therefore, patients cannot be diagnosed by sigmoidoscopy alone[1]. In 1982, Tedesco et al[3] carried out a prospective study on patients diagnosed with pseudomembranous colitis. They stated that 77.3% of the patients were successfully diagnosed through sigmoidoscopy; but in 13.6% of the patients, pseudomembranous colitis occurred between 24 and 60 cm from the anus, and it occurred more than 60 cm from the anus in 9.1% of the patients. Furthermore, in 1999, Lee et al[4] studied the clinical characteristics of C. difficile-associated diseases and claimed that because less than 10% of patients had lesions in the ascending colon alone without invading the descending colon, sigmoidoscopy was sufficient, and colonoscopy was not needed.

When C. difficile occurs in the cecum, it can be observed on a CT scan as an “accordion sign”, which is caused by the invasion of the tissues surrounding the cecum and cecal bulb as well as a thickening of the cecal folds. Based on these CT scan results, appendicitis should be distinguished from typhlitis, pseudomembranous colitis, inflammatory diseases, diverticulitis of the cecum, inflammatory bowel diseases, cecal volvulus, pneumatosis intestinalis, ischemia and necrosis, solitary cecal ulcer syndrome, and tumors in the cecum in a patient suffering from right lower abdominal pain[5]. Our patient’s CT scan showed the “accordion sign.”

C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that is resistant to antibiotic treatments by forming spores. C. difficile is part of the normal flora in the intestine of infants, but this is rarely the case with older children or adults. However, if the normal flora is altered due to antibiotic or antitumor treatments or infections with pathogens, such as Salmonella or Shigella, C. difficile colonization can occur. Therefore, the normal flora in the colon appears to inhibit the growth of C. difficile. C. difficile secretes powerful exotoxins called toxin A and toxin B, which induce tissue damage to the colon. However, depending on the strain, some exotoxins may be less toxic than others or not toxic at all. Nonetheless, because the level of toxicity is not proportional to the severity of the disease, in general, these toxins are reported as either positive or negative[1].

Almost every antibiotic that shows activity against bacteria can induce antibiotic-associated colitis. The antibiotics that most commonly cause antibiotic-associated colitis are cephalosporin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin; the ones that cause it less frequently include penicillin, excluding ampicillin, and macrolides (erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin). In addition, antibiotics that occasionally cause antibiotic-associated colitis include fluoroquinolone, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, metronidazole, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol. It has not yet been clearly established whether sulfonamide, parenteral aminoglycosides, or parenteral vancomycin-as well as other antimicrobial agents against fungi, mycobacteria, parasites, and viruses-can induce antibiotic-associated colitis.

Moreover, C. difficile-associated colitis can occur in patients who (1) have had prolonged hospitalization; (2) share a cubicle or ward with a patient suffering from antibiotic-associated colitis; (3) are old; (4) recently had surgery, in particular, gastrointestinal surgery; (5) suffer from intestinal obstruction; or (6) have a malignant tumor[6].

The most distinctive antibiotic-associated colitis induced by C. difficile may be pseudomembranous colitis. For example, over 95% of patients diagnosed with pseudomembranous colitis have a positive stool toxin assay. A close examination of their pseudomembrane reveals few normal tissues and raised exudative plaques that have hemorrhagic edematous mucosa with perforated areas. Such plaques can grow and become merged across bowel segments in the final stage of the disease.

The clinical characteristics of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis vary. One of the most common characteristics is a large amount of watery diarrhea without blood or mucus. Most patients experience severe convulsive abdominal pain and tenderness, fever, and leukocytosis. However, symptoms can vary greatly. On one hand, some patients suffer from diarrhea and show no systemic symptoms. On the other hand, some patients present severe systemic toxicity, high fevers up to 40.0 °C-40.6 °C, and peripheral leukocytosis up to 50000/mm3. The results of stool examinations usually show white blood cells.

If left untreated, the clinical course varies between patients. Some patients experience immediate relief from symptoms after discontinuing the drug, while others continuously produce a large amount of feces up to week 8, which can ultimately lead to hypoalbuminemia or electrolyte imbalance. There also have been some reports of severe patients with toxic megacolon and enterobrosia. The mortality rate of severe patients is approximately 30%, while the symptoms of most patients with mild symptoms improve simply by discontinuing antibiotics. In most patients, symptoms begin to appear 4-10 d after antibiotic administration. However, approximately 25% of patients do not experience any symptoms until they discontinue antibiotics, and a few begin to show symptoms after 4 wk of administration. It has been reported that in some cases, symptoms occur within several hours of antibiotic administration and sometimes even after a single administration of antibiotic as a surgical prophylactic measure[7].

Our aged patient had risk factors for developing pseudomembranous colitis and had a history of taking a 3rd-generation cephalosporin antibiotic (cefixime) for approximately 2 wk. On sigmoidoscopy, we observed several pseudomembranes limited to the cecum and the ascending colon, and the pseudomembranes were proven by biopsy. Moreover, the patient’s stool toxin assay was positive (0.09).

Pseudomembranous colitis can be treated by discontinuing the antibiotic that has been used and switching to a conservative treatment alone. In such cases, approximately 30% of patients show improved symptoms in approximately 10 d; however, patients with severe enteritis can also take 250 mg of metronidazole orally 4 times daily for approximately 7-14 d. When oral administration is impossible due to paralytic ileus or megacolon, 500 mg can be administered every 6 h through a jugular vein. Because metronidazole is well absorbed in the upper gastrointestinal tract, the downside of oral administration is that its concentrations can decrease in the feces. However, pseudomembranous colitis can increase the permeability of the colonic mucosa and subsequently allow metronidazole to be delivered to the lumen of the colon. Metronidazole is much more affordable than vancomycin, and due to recent concerns over Enterococcus, which is resistant to vancomycin, metronidazole is the primary choice to treat antibiotic-associated colitis[8].

Typically, 125 or 500 mg of vancomycin is administered orally 4 times daily for 7-14 d. The 125 mg dose is cheaper than the 500 mg dose, but they appear to have similar treatment effects. Because vancomycin is rarely absorbed when orally administered, the fecal concentration remains high. However, it is less effective when it is administered through a jugular vein, as the concentration is lower in the lumen of the colon. It can be argued that oral vancomycin is highly effective in treating antibiotic-associated colitis because there is no report of C. difficile being resistant to vancomycin. Nevertheless, it is still much more expensive than metronidazole, and considering concerns over vancomycin-resistant enterococci, metronidazole should be the primary choice to treat antibiotic-associated colitis; vancomycin should only be used in cases in which metronidazole cannot be used or in patients who do not respond to metronidazole[9,10].

We administered 250 mg of metronidazole orally to our patient 4 times daily; after 3 d, the right lower abdominal pain, tenesmus, and frequent watery diarrhea disappeared. The reoccurrence rate of pseudomembranous colitis after treatment is reported to be approximately 20%, and possible causes of reoccurrence are reinfections by remaining strains and spore formation[11]. Our patient was administered metronidazole for 7 d total, and based on the result of a sigmoidoscopy performed one month later, we were able to confirm that his intestinal mucosa had returned to normal.

In conclusion, even when right lower abdominal pain is the major clinical manifestation, if the patient has abnormal bowel habits and a recent history of antibiotic administration, even without the presence of fever, chills, or watery diarrhea (which are common clinical characteristics of pseudomembranous colitis), we recommend that pseudomembranous colitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

P- Reviewer Amarapurkar D S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Kelly CP, Pothoulakis C, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile colitis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 935] [Cited by in RCA: 876] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coyne JD, Dervan PA, Haboubi NY. Involvement of the appendix in pseudomembranous colitis. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:70-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tedesco FJ, Corless JK, Brownstein RE. Rectal sparing in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:1259-1260. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lee CR, Lee JG, Jo YS, Yu HM, Kim WH, Lee KWl. A clinical investigation of clostridium difficile-associated disease. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1999;33:338–347. |

| 5. | Gluecker TM, Williamson EE, Fletcher JG, Hough DM, Huppert BJ, Carlson SK, Casey MB, Farrell MA. Diseases of the cecum: a CT pictorial review. Eur Radiol. 2003;13 Suppl 6:L51-L61. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bartlett JG. Pseudomembranous colitis and antibiotic associated colitis. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s gastrointestinal liver disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders 1998; 1633–1647. |

| 7. | Kasper DI, Zaleznik DF. Gas gangrene antibiotic-associated colitis and other clostridial infections. Harrison’s principle of internal medicine. 15th ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill 2003; 942–943. |

| 8. | Fekety R. Pseudomembranous colitis. Cecil textbook of medicine. 21st ed. Philadelphia (PA): WB Sauders 2000; 1670–1673. |

| 9. | Kasper DI, Zaleznik DF. Gas gangrene antibiotic-associated colitis and other clostridial infections. Harrison’s principle of internal medicine. 14th ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill 1998; 906-910. |

| 10. | Lamont JT, Kelly CP. Bacterial infections of the colon. Textbook of gastroenterology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 1999; 1952–1957. |

| 11. | Akbar DH, Al-Shehri HZ, Al-Huzali AM, Falatah HI. A case of rifampicin induced pseudomembraneous colitis. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1391-1393. [PubMed] |