Published online Mar 27, 2013. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i3.37

Revised: December 13, 2012

Accepted: December 25, 2012

Published online: March 27, 2013

Processing time: 149 Days and 8.6 Hours

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is the most common cause of healthcare associated infectious diarrhea. In the last decade, the incidence of C. difficile infection has increased dramatically. The virulence of C. difficile has also increased recently with toxigenic strains developing. C. difficile is generally a disease of the colon and presents with abdominal pain and diarrhea due to colitis. However, C. difficile enteritis has been reported rarely. The initial reports suggested mortality rates as high as 66%. The incidence of C. difficile enteritis appears to be increasing in parallel to the increase in colonic infections. We present two cases of patients who had otherwise uneventful abdominal surgery but subsequently developed C. difficile enteritis. Our literature review demonstrates 81 prior cases of C. difficile enteritis described in case reports. The mortality of the disease remains high at approximately 25%. Early recognition and intervention may reduce the high mortality associated with this disease process.

-

Citation: Dineen SP, Bailey SH, Pham TH, Huerta S.

Clostridium difficile enteritis: A report of two cases and systematic literature review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 5(3): 37-42 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v5/i3/37.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v5.i3.37

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is a common nosocomial infection caused by a gram-negative spore forming organism that most commonly leads to pseudomembranous colitis[1,2]. The incidence of C. difficile infection has been increasing rapidly since the early 2000s[2,3]. The rate of C. difficile infection nearly tripled between 1996 and 2005[2]. The number of severe cases of C. difficile infection is also rising; the number of fatal cases in England rose from approximately 500 in 1999 to nearly 3400 in 2006[2]. The increasing severity of disease may be due to a rise in an epidemic strain, NAP1/BI/027, which produces toxin A and B in significantly greater quantity compared to the normally occurring strain. C. difficile resides in the colon and risk factors for infection, such as antibiotic use, are generally those that alter normal colonic flora. However, we present two cases of patients diagnosed and treated with C. difficile enteritis. Due to the rare nature of this disease we reviewed the literature on the subject and present data to suggest increasing recognition of this manifestation of C. difficile.

The first patient is a 54-year-old Caucasian male with ulcerative colitis who underwent a total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy in 1997. He developed a parastomal hernia that was becoming increasingly symptomatic. Following a discussion with the patient regarding the risks and benefits of parastomal hernia repair, he underwent an exploratory laparotomy with enterolysis, parastomal hernia repair and re-siting of the ileostomy. The hernia defect was repaired primarily with a biologic mesh underlay (Alloderm, Lifecell®). He received one preoperative dose of cefoxitin; consistent with preoperative antibiotic guidelines. The operation was uneventful. His postoperative course was uncomplicated; on postoperative day 4 he was tolerating a regular diet and had normal ileostomy output. He was subsequently discharged home.

Twenty-four hours later, he returned to the hospital emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain and feculent vomiting. Vital signs on arrival were notable for a temperature of 38.5 °C, heart rate of 130 beats per minute and blood pressure of 150/90 mmHg. On physical exam his abdomen was diffusely tender to palpation without peritoneal signs. The ileostomy was viable and there was gas and a small amount of fluid noted in the ostomy bag. A nasogastric tube was placed and returned 1600 mL of feculent effluent.

Laboratory examination revealed a white blood cell count of 5400 cells/mm3, hemoglobin of 16 g/dL, and 192 000 platelets/mm3 and a serum lactate of 2.1 mg/dL. An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan obtained in the emergency department revealed mildly dilated, fluid filled small bowel without a transition point. There was a small amount of free fluid and air which was consistent with the history of recent laparotomy. Blood cultures were obtained in the emergency department.

He was transferred to the intensive care unit for fluid resuscitation and started on broad-spectrum antibiotics. Serial abdominal exams were performed over the course of the next several hours, and he began to stabilize clinically. Notably, his tachycardia began to resolve and his urine output increased. Additionally, during this time, his ileostomy began to produce copious amounts of fluid and gas requiring frequent ostomy bag changes. The following day, his blood cultures returned positive for Enterococcus and his stool studies from his stoma output were positive for C. difficile.

Treatment for C. difficile was initiated with oral metronidazole but was subsequently changed to a combination of intravenous metronidazole and vancomycin enemas as the patient was not tolerating oral intake well. On hospital day 2, the antibiotic regimen used to treat the bacteremia was tailored to intravenous vancomycin alone based on sensitivity information. The patient improved with his antibiotic treatment and was transitioned to oral vancomycin for treatment of C. difficile. He was treated for a total of 14 d and he had complete resolution of his symptoms.

The second case is a 48-year-old male patient with a history of diverticulitis who presented with left lower quadrant abdominal pain. His vital signs were normal on admission. A CT scan revealed inflammation of the sigmoid colon without evidence of a discrete fluid collection. The patient was initially started on intravenous antibiotics. However, approximately 24 h following admission, the patient developed worsening abdominal pain. His abdominal examination demonstrated worsening tenderness, with diffuse rebound and guarding. After discussion of operative risks he was taken to the operating room for exploration.

The sigmoid colon demonstrated only a focal area of perforation with moderate inflammation. A sigmoidectomy was performed with healthy proximal tissue and normal rectum. A primary anastomosis was performed using an EEA stapling device. A diverting ileostomy was performed to protect the anastomosis. The patient received 24 h of antibiotic treatment prior to operation which included three doses each of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. Postoperatively, the patient developed an ileus which resolved on postoperative day 6. He was tolerating a diet following this. On postoperative day 8, the patient experienced significantly increased output from his ileostomy (greater than 2 L). A C. Difficile toxin sent from the ileostomy returned positive. The patient was started on intravenous metronidazole and improved. He was transitioned to oral medications upon discharge to complete a 14 d course.

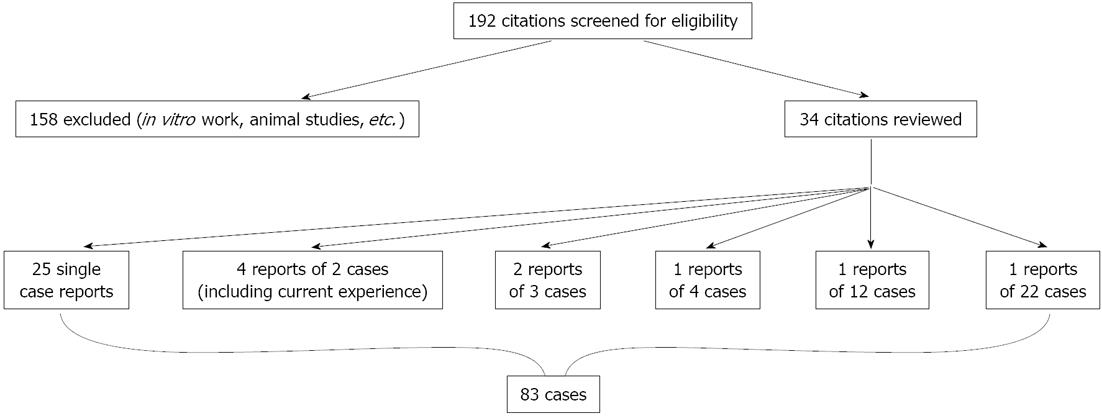

A systematic literature review was conducted by searching PubMed for the terms “enteritis” and “Clostridium difficile”. One hundred and ninety-two citations were screened. One-hundred and fifty-eight were excluded based on review of title or abstract. Thirty-four citations were reviewed and the references of individual reports were hand searched to identify any missed reports. Data was extracted from individual case reports. All patients were symptomatic and tested positive for C. difficile. There were 34 reports identified from this search (Figure 1). We did not perform a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of the data and lack of randomized trials.

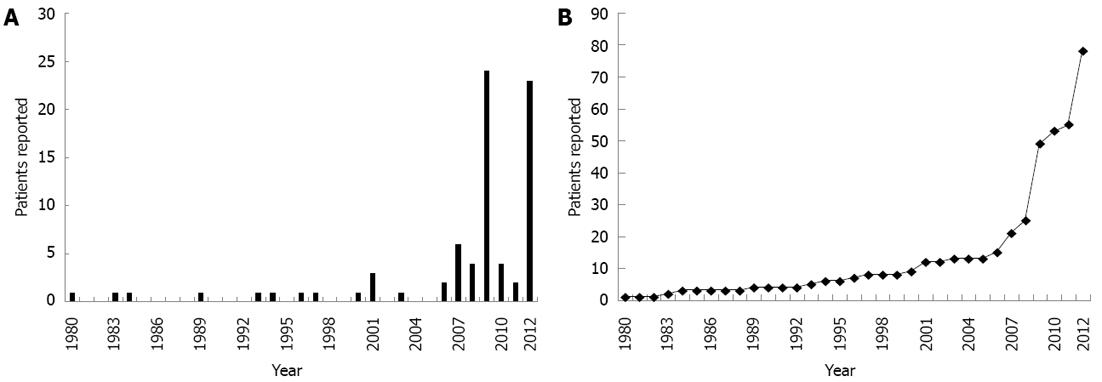

There were 81 cases of C. difficile enteritis found in the literature[4-37], with the addition of our cases, the total number of cases is now 83. Figure 2 illustrates that the number of cases has increased considerably in the last decade. There were 9 cases reported between the years 1980 and 2000. Since then there have been 73 cases reported. The mortality from the first 9 cases reported was 67% (6/9). The overall mortality of the 83 cases published is 23%. The average age of patients is 54 ± 2.44 years. Male patients constituted 53% of the cohort. Antibiotic use in the prior 4 wk was 71% and the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease was 41%. Twenty-one of 83 patients died resulting in a mortality rate of 23%.

C. difficile is the most common cause of health care-associated infectious diarrhea[3]. As first described, C. difficile colitis was thought to be associated with the exclusive use of clindamycin administration[2]. Ironically, the bacteria that was difficult to grow (thus the difficile) is now increasing with dramatic incidence[2,38]. The increase in incidence is due, in part, to the highly virulent NAP1/BI/027 strain of C. difficile. In the United States, the frequency of C. difficile infection has doubled in the past 10 years[38]. The understanding of C. difficile and its pathophysiology has increased substantially over the past few decades. Severe C. difficile infection is being reported more frequently in patients not previously thought to be at high risk, including children[38,39]. It is possible that C. difficile enteritis is less dependent on alterations in colonic flora to develop. C difficile enteritis has previously been considered a rare disease. However, as highlighted in our review, the incidence of this also appears to be increasing.

Predisposing factors to C. difficile infection include prior antibiotic use; which is thought to alter the colonic flora, allowing C. difficile to proliferate. Many case reports, including ours, would suggest that previous antibiotic use is also associated with C. difficile enteritis. Lavallée et al[19] report that ten of twelve patients with ileal C. difficile had recent antibiotic administration (one did not have recent antibiotic use and one was not documented). Similarly, Lundeen et al[20] present 6 cases of C. difficile enteritis in which all 6 cases had recent antibiotic exposure. However, Tsiouris et al[30] report 22 cases in which the association with prior antibiotic use is less strong. Of the 22 patients in this series, only 22.7% demonstrated recent use of antibiotics. Based on our review, the association is still high, as 71% of patients had received antibiotics within 4 wk of presentation with C. difficile enteritis.

It is believed that gastric acid is a key mechanism of defense against ingested pathogens[1]. C. difficile has been identified as a pathogen in animals and has been identified in some food products[40]. Therefore, it is possible that transmission from ingested meats may occur[40]. Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and H2-blockers are frequently used for gastric acid suppression. Acid suppressive therapy has been demonstrated to significantly increase the risk for C. difficile infection[1,41]. The patient in Case 1 was treated preoperatively with a PPI for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Case 2 was not on outpatient therapy, but did receive a PPI postoperatively. This association is not entirely clear, however, as Lundeen et al[20] reported six cases, in which only one patient was on acid reducing therapy.

The pathophysiology of C. difficile enteritis is not well understood. Patients with an ileostomy may develop a metaplasia of the terminal end, creating an environment more similar to the colonic environment[42]. Additionally, changes in the intestinal flora have been noted after ileostomy[43]. Testore et al[44] isolated C. difficile from jejunum in asymptomatic human autopsy specimens. This supports the theory that small bowel may act as a reservoir. Kralovich et al[15] demonstrated in vivo that a patient with a jejunal-ileal bypass developed C. difficile infection in the defunctionalized limb. In addition to alterations in the host, changes in the pathogen may also be responsible for the development of C. difficile enteritis. Small bowel mucosa requires a higher concentrations of toxin for infection to occur[45]. In this case, the toxigenic NAP1/BI/027 strain may be more capable of causing small bowel infection. This is hypothetical at this point, but the increased recognition of C. difficile enteritis is compatible with the timing of the rise in NAP1/BI/027. This strain has been confirmed as the causative agent in one case of C. difficile enteritis[19]. We did not specifically test for NAP1/BI/027 strain and, therefore, cannot determine if this was a predisposing factor in our patients.

The diagnosis of C. difficile enteritis requires a high index of suspicion. As many patients may not initially be suspected of C. difficile infection, CT scan evidence may be useful. Wee et al[33] reviewed CT scan findings in four patients with C. difficile enteritis. They suggest that ascites and fluid-filled small bowel in the presence of mild mesenteric stranding could be considered consistent with C. difficile enteritis. Our patient in Case 1 demonstrated fluid filled loops of small bowel and a moderate amount of ascites. This was initially thought to be due to his recent surgery. However, these findings are consistent with the reported CT findings of small bowel C. difficile.

Treatment for C. difficile enteritis is generally similar to that for colonic infections. Oral metronidazole is considered standard first line therapy. However, Follmar et al[8] report the use of vancomycin for metronidazole resistant C. difficile. Severe C. difficile infection may be better treated with vancomycin[46,47]. In our patient, due to his ileus and his severe clinical status, we elected to use intravenous metronidazole and vancomycin enemas for his initial treatment.

It should be noted that our review is focused on case reports. There is no prospective data on the incidence of C. difficile enteritis. Therefore, it is not possible to know whether the apparent increase in cases is a true increase in incidence or if there is simply more reporting of the disease. However, even in the context of simply more reporting, the mortality remains high and increased recognition will still remain a priority.

The mortality of C. difficile enteritis has historically been considered very high as the initial 9 reports demonstrated a mortality of 66%. However, as the experience has steadily accumulated, the mortality rate appears to be decreasing. Our report of a mortality rate of 25.3% is lower than earlier reports, but remains substantial. This clinical entity is still rare and requires a high index of suspicion to initiate treatment early. As the use of antibiotics, immunosuppressive agents, and the age of the patient population will all continue to increase it is likely that C. difficile infections, including C. difficile enteritis will only continue to increase. Awareness of this process and efforts to determine the optimal treatment will continue to be necessary.

P- Reviewer Tarchini G S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Dial S, Delaney JA, Barkun AN, Suissa S. Use of gastric acid-suppressive agents and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease. JAMA. 2005;294:2989-2995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 701] [Cited by in RCA: 670] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile--more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1932-1940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1035] [Cited by in RCA: 1021] [Article Influence: 60.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Loo VG, Bourgault AM, Poirier L, Lamothe F, Michaud S, Turgeon N, Toye B, Beaudoin A, Frost EH, Gilca R. Host and pathogen factors for Clostridium difficile infection and colonization. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1693-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 590] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boland E, Thompson JS. Fulminant Clostridium difficile enteritis after proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastamosis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2008;2008:985658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Causey MW, Spencer MP, Steele SR. Clostridium difficile enteritis after colectomy. Am Surg. 2009;75:1203-1206. [PubMed] |

| 6. | El Muhtaseb MS, Apollos JK, Dreyer JS. Clostridium difficile enteritis: a cause for high ileostomy output. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fleming F, Khursigara N, O’Connell N, Darby S, Waldron D. Fulminant small bowel enteritis: a rare complication of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:801-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Follmar KE, Condron SA, Turner II, Nathan JD, Ludwig KA. Treatment of metronidazole-refractory Clostridium difficile enteritis with vancomycin. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2008;9:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Freiler JF, Durning SJ, Ender PT. Clostridium difficile small bowel enteritis occurring after total colectomy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1429-131; discussion 1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gagandeep D, Ira S. Clostridium difficile enteritis 9 years after total proctocolectomy: a rare case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:962-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hayetian FD, Read TE, Brozovich M, Garvin RP, Caushaj PF. Ileal perforation secondary to Clostridium difficile enteritis: report of 2 cases. Arch Surg. 2006;141:97-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Holmer C, Zurbuchen U, Siegmund B, Reichelt U, Buhr HJ, Ritz JP. Clostridium difficile infection of the small bowel--two case reports with a literature survey. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jacobs A, Barnard K, Fishel R, Gradon JD. Extracolonic manifestations of Clostridium difficile infections. Presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:88-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim KA, Wry P, Hughes E, Butcher J, Barbot D. Clostridium difficile small-bowel enteritis after total proctocolectomy: a rare but fatal, easily missed diagnosis. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:920-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kralovich KA, Sacksner J, Karmy-Jones RA, Eggenberger JC. Pseudomembranous colitis with associated fulminant ileitis in the defunctionalized limb of a jejunal-ileal bypass. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:622-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kuntz DP, Shortsleeve MJ, Kantrowitz PA, Gauvin GP. Clostridium difficile enteritis. A cause of intramural gas. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1942-1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kurtz LE, Yang SS, Bank S. Clostridium difficile-associated small bowel enteritis after total proctocolectomy in a Crohn’s disease patient. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:76-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | LaMont JT, Trnka YM. Therapeutic implications of Clostridium difficile toxin during relapse of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1980;1:381-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lavallée C, Laufer B, Pépin J, Mitchell A, Dubé S, Labbé AC. Fatal Clostridium difficile enteritis caused by the BI/NAP1/027 strain: a case series of ileal C. difficile infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:1093-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lundeen SJ, Otterson MF, Binion DG, Carman ET, Peppard WJ. Clostridium difficile enteritis: an early postoperative complication in inflammatory bowel disease patients after colectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:138-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Malkan AD, Pimiento JM, Maloney SP, Palesty JA, Scholand SJ. Unusual manifestations of Clostridium difficile infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2010;11:333-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mann SD, Pitt J, Springall RG, Thillainayagam AV. Clostridium difficile infection--an unusual cause of refractory pouchitis: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:267-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miller DL, Sedlack JD, Holt RW. Perforation complicating rifampin-associated pseudomembranous enteritis. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1082. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Navaneethan U, Giannella RA. Thinking beyond the colon-small bowel involvement in clostridium difficile infection. Gut Pathog. 2009;1:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Peacock O, Speake W, Shaw A, Goddard A. Clostridium difficile enteritis in a patient after total proctocolectomy. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shen B, Remzi FH, Fazio VW. Fulminant Clostridium difficile-associated pouchitis with a fatal outcome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:492-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shortland JR, Spencer RC, Williams JL. Pseudomembranous colitis associated with changes in an ileal conduit. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:1184-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Testore GP, Nardi F, Babudieri S, Giuliano M, Di Rosa R, Panichi G. Isolation of Clostridium difficile from human jejunum: identification of a reservoir for disease? J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:861-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tjandra JJ, Street A, Thomas RJ, Gibson R, Eng P, Cade J. Fatal Clostridium difficile infection of the small bowel after complex colorectal surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:500-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tsiouris A, Neale JA, Reickert CA, Times M. Clostridium difficile of the ileum following total abdominal colectomy, with or without proctectomy: who is at risk? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:424-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tsutaoka B, Hansen J, Johnson D, Holodniy M. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous enteritis due to Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:982-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vesoulis Z, Williams G, Matthews B. Pseudomembranous enteritis after proctocolectomy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:551-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wee B, Poels JA, McCafferty IJ, Taniere P, Olliff J. A description of CT features of Clostridium difficile infection of the small bowel in four patients and a review of literature. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:890-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Williams RN, Hemingway D, Miller AS. Enteral Clostridium difficile, an emerging cause for high-output ileostomy. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:951-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wood MJ, Hyman N, Hebert JC, Blaszyk H. Catastrophic Clostridium difficile enteritis in a pelvic pouch patient: report of a case. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:350-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yafi FA, Selvasekar CR, Cima RR. Clostridium difficile enteritis following total colectomy. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:73-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yee HF, Brown RS, Ostroff JW. Fatal Clostridium difficile enteritis after total abdominal colectomy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:45-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tschudin-Sutter S, Widmer AF, Perl TM. Clostridium difficile: novel insights on an incessantly challenging disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:405-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Benson L, Song X, Campos J, Singh N. Changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in children. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1233-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Songer JG, Trinh HT, Killgore GE, Thompson AD, McDonald LC, Limbago BM. Clostridium difficile in retail meat products, USA, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:819-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Howell MD, Novack V, Grgurich P, Soulliard D, Novack L, Pencina M, Talmor D. Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:784-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Apel R, Cohen Z, Andrews CW, McLeod R, Steinhart H, Odze RD. Prospective evaluation of early morphological changes in pelvic ileal pouches. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:435-443. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Neut C, Bulois P, Desreumaux P, Membré JM, Lederman E, Gambiez L, Cortot A, Quandalle P, van Kruiningen H, Colombel JF. Changes in the bacterial flora of the neoterminal ileum after ileocolonic resection for Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:939-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Testore GP, Pantosti A, Cerquetti M, Babudieri S, Panichi G, Gianfrilli PM. Evidence for cross-infection in an outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea in a surgical unit. J Med Microbiol. 1988;26:125-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Triadafilopoulos G, Pothoulakis C, O’Brien MJ, LaMont JT. Differential effects of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B on rabbit ileum. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:273-279. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Cocanour CS. Best strategies in recurrent or persistent Clostridium difficile infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2011;12:235-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 945] [Cited by in RCA: 938] [Article Influence: 52.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |