Published online Jul 27, 2012. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i7.185

Revised: January 5, 2012

Accepted: February 23, 2012

Published online: July 27, 2012

Autoimmune pancreatitis can mimic pancreatic cancer in its clinical presentation, imaging features and laboratory parameters. Differentiating between those two entities requires implementation of clinical judgment and experience along with objective parameters that may suggest either condition. Few strategies have been proposed for the surgeon to implement when facing borderline cases. The following case is an example of a clinical scenario compatible with an accepted algorithm for diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, which eventually proved wrong. We present a 75-year-old patient who was admitted for obstructive jaundice. Imaging features were highly suggestive for pancreatic cancer as was the carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) level, leading to a decision for surgery. Pathological examination revealed autoimmune pancreatitis. Though no frank carcinoma was found, premalignant ductal changes of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) I and PanIN II were discovered throughout the pancreatic duct. Caution is advised when relying on the combination of highly suggestive radiology features and elevated levels of CA 19-9 in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. When the tissue diagnosis is not conclusive, obtaining IgG4 and antinuclear Ab levels is advised, to rule out the rare possibility of autoimmune pancreatitis. Patients with autoimmune pancreatitis should be followed carefully as precancerous lesions may accompany the benign disease and the correlation of these two entities has not been ruled out.

- Citation: Brauner E, Lachter J, Ben-Ishay O, Vlodavsky E, Kluger Y. Autoimmune pancreatitis misdiagnosed as a tumor of the head of the pancreas. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4(7): 185-189

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v4/i7/185.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v4.i7.185

Autoimmune pancreatitis is a rare type of chronic pancreatitis that can closely mimic pancreatic cancer. These two entities can present with obstructive jaundice and/or a pancreatic mass. Both diseases can cause weight loss and abdominal discomfort[1]. In both diseases abnormally elevated levels of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) have been documented[2]. Making a correct differential diagnosis between the two conditions is of paramount importance as the treatment modalities are essentially different. Nevertheless one should not rest once autoimmune pancreatitis has been diagnosed, as precancerous lesions may also be discovered and could be the result of ongoing tissue insult.

We present a patient who underwent total pancreatectomy for a mass lesion in the head of the pancreas accompanied with elevated CA 19-9, for the pre-operative working diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Histological examination was consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis although precancerous changes were also discovered throughout the pancreatic duct.

A 75-year-old patient presented to the hospital for investigation of recent onset jaundice. The patient complained of anorexia, weight loss, dark urine and pale-colored stools. He had been recently diagnosed with new onset diabetes and was put on a diet by his General Practitioner. No other clinical symptoms were revealed from the patient’s past medical history.

Lab tests revealed a total bilirubin level of 9.8 mg% and direct bilirubin of 8.4 mg%. Aspartate transaminase was 474 U/L (normal: 10-35 U/L), alanine aminotransferase was 1188 U/L (normal: 9-52 U/L), γ-glutamyltransferase was 733 U/L (normal: 0-42 U/L), and alkaline phosphatase 608 U/L (normal: 30-120 U/L). Serum CA 19-9 was 476 U/mL (normal < 37 U/mL). No other laboratory abnormalities were noted.

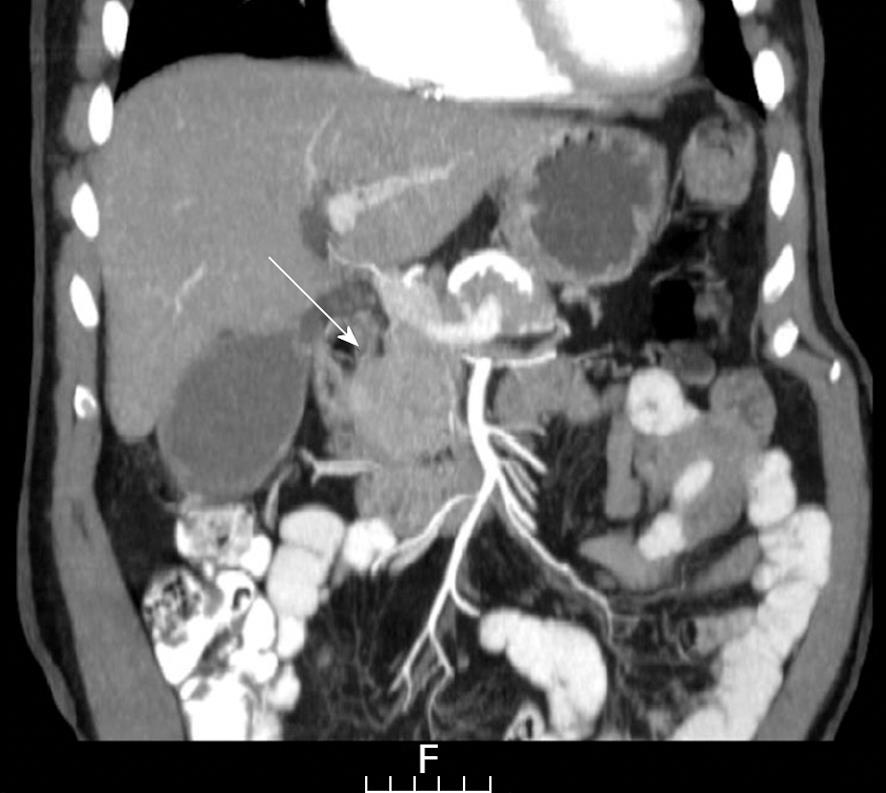

For the investigation of obstructing jaundice a sonography of the upper abdomen was carried out, revealing a dilated common bile duct (CBD). As no biliary stones were observed, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was conducted which showed a distended CBD with narrowing at the level of the head of the pancreas where a hypodense lesion was noted (Figures 1 and 2). No vascular involvement was seen.

For the purpose of further evaluation and possibly obtaining tissue samples an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was the next step. A twenty nine millimeter, hypo-echoic, homogenous lesion was revealed at the head of the pancreas. Contrary to the tomographic picture, the splenic and superior mesenteric arteries as well as the portal vein had no clear margins with the lesion. The head of the pancreas was seen to be edematous and lobulated and the rest of the organ was atrophic. An EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) revealed normal acinary pancreatic cells.

Though no tissue for supporting the diagnosis was available, the strong suspicion of a pancreatic tumor resulted in surgery being carried out.

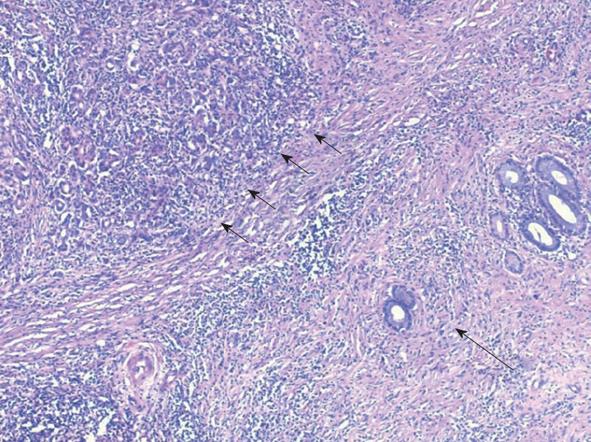

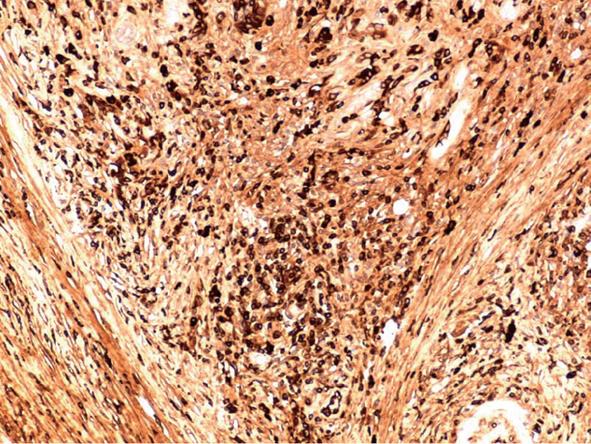

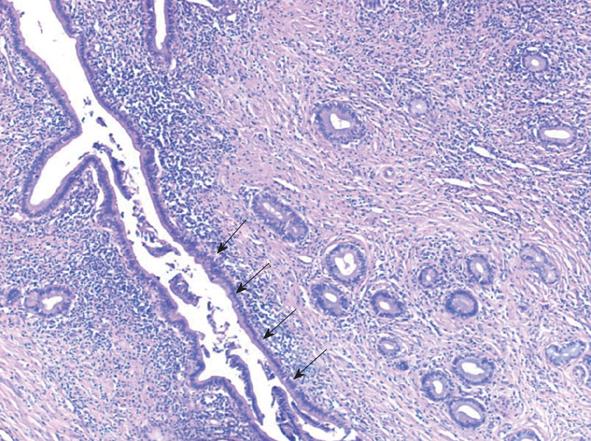

The surgery began with an exploratory laparoscopy which did not show peritoneal spread or metastatic lesions. The abdomen was then opened and thorough exploration was carried out. A firm well-circumscribed mass was found extending from the head to the neck of the pancreas and extending medial to the portal vein. The vascular structures were not involved in the suspected tumoral mass. Due to the tumor size and its extension medial to the portal vein as well as the atrophic tail of the pancreas, a total pancreatectomy and splenectomy was chosen. The patient recovered from surgery uneventfully. The pathological examination revealed marked diffuse chronic inflammation with multiple plasma cells, lymphocytes, fibrosis and atrophy of the pancreas (Figure 3). Twenty one lymph nodes were negative for any pathology. Twenty plasma cells per high power field (a significant number) were positive for IgG4 (Figure 4). The pancreatic tissue showed ductal alteration with extensive pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) I and II changes (Figure 5).

The combination of a biliary obstruction, imaging of a discrete pancreatic lesion and high serum levels of CA 19-9 is highly suggestive of pancreatic malignancy.

A cut-off level of CA 19-9 which might discriminate malignant from benign pancreatic pathologies has been investigated and reported. Morris-Stiff et al[3] suggested a cut-off level of 70.5 U/mL to distinguish between malignant and benign lesions with a sensitivity of 82.1% and a specificity of 85.9%. When standard radiology was added to the decision making algorithm the sensitivity and specificity were 97.2% and 88.7%, respectively. Marrelli et al[4] suggested a cut-off level of 90 U/mL. CA 19-9 levels in excess of 300 U/mL with a mass lesion in patients with chronic pancreatitis were indicative of malignancy in 100% of the cases reported by Bedi et al[5]. In a review of the literature comparing serum CA 19-9 levels in patients with pancreatic cancer with control groups, CA 19-9 was found to have an overall mean sensitivity of 81% and a mean specificity of 90%. Increasing the cut-off point to 100 U/mL, improved specificity to 98% and reduced sensitivity to 68%. At a cut-off point of 1000 U/mL, specificity was 99.8% and sensitivity was only 41%. CA 19-9 lacks sensitivity for early or small-diameter pancreatic cancers. Thus, only 50% of patients with pancreatic cancers < 3 cm were found to have elevated levels of CA 19-9[6]. In our patient, high levels of bilirubin as a result of biliary obstruction were present. Though a positive correlation between obstructive jaundice and CA 19-9 elevation was observed and documented in the past[7], CA 19-9 levels have been shown to be significantly higher in patients with obstructive jaundice as a result of malignancies compared to those with benign diseases[8]. In our patient the high level of the marker despite biliary obstruction turned our thinking towards malignancy, an assumption reinforced by imaging.

Autoimmune pancreatitis may mimic pancreatic adenocarcinoma in its clinical presentation. Various investigators have tried to focus on this diagnostic dilemma, as the consequences in terms of best treatment options are dramatically different. In a report by Hardacre et al[9], autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer patients had very similar preoperative presentations. The only retrospectively identified variable that might have distinguished between autoimmune pancreatitis and carcinoma was the presence of a discrete mass in the pancreas on CT scan[9].

Japanese investigators[10], tried to find characteristics to discriminate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer and to establish a useful discriminating algorithm and diagnostic strategy. This group found no differences regarding symptoms, physical findings and the level of tumor markers. The Japanese strategy regarding mass-forming pancreatic lesions was based on imaging features of CT and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and the level of IgG4. Enhancement of the enlarged pancreas, a capsule-like rim or the presence of extra-pancreatic lesions, were the features on CT scan associated with autoimmune pancreatitis[10]. None of these features were identified in the present patient. A long narrowed main pancreatic duct, skipped lesions of the main pancreatic duct and maximal upstream main pancreatic duct diameter of < 5 mm were the features on ERCP associated with autoimmune pancreatitis[10].

Chari et al[11] retrospectively compared 48 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis presenting with obstructive jaundice and 100 patients with pancreatic cancer. Serum CA 19-9 of more than 150 U/mL was more than 90% specific for pancreatic cancer[11]. Features of pancreatic low density mass, pancreatic duct cut-off, distal atrophy and metastasis were highly suggestive of pancreatic cancer. The presence of focal pancreatic enlargement without features suggestive of pancreatic cancer or a normal appearing pancreas, were indeterminate. According to the above American strategy suggested by Chari, patients with any of the imaging features highly suggestive of pancreatic cancer should be managed as cancer.

None of the strategies above rely on tissue diagnosis or positive aspiration when the imaging feature is highly suggestive of, or directing towards, exclusion of cancer.

In the present patient, a discrete mass with a hypo-dense center was found on CT scan, also imaged by EUS, which delineated a measurable mass in the head of the pancreas. Highly elevated levels of CA 19-9 and the absence of other stigmata suggestive of an inflammatory processes in the pancreas resulted in a decision to operate. The pathological results now call into question the diagnostic strategy to be implemented.

The importance of EUS in the role of pancreatic mass lesions has been described[12]. The risks of EUS are low, and generally are not greatest for cases undergoing FNA[13]. Although EUS-guided FNA is not universally accepted as necessary if surgery seems appropriate, the current case highlights the importance of a negative or benign finding on FNA: such cases should mandate re-consideration of alternative diagnoses such as autoimmune pancreatitis.

Although autoimmune pancreatitis was the disease which lead to this patient’s clinical presentation, we were surprised at its association with a premalignant process in the inflamed organ in the form of PanIN I-II. In searching relevant literature, only one previous mentioned was found of the presence of both autoimmune pancreatitis and PanIN lesions in the same patient[14]. However, this association may be more common than previously appreciated as low-grade PanINs have been identified in the normal pancreas in 16%-80% of adults, not harboring an invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma or any other cancer[15-18].

Nevertheless, the present case can still serve as a warning that the two entities may not be mutually exclusive. Autoimmune pancreatitis, similarly to chronic pancreatitis, might serve as a template for the evolution of premalignant changes from PanIN I to II to III to carcinoma. As more and more cases of autoimmune pancreatitis are discovered and investigated, a close follow up of those cases is justified and recommended. The long-term prognosis of patients with autoimmune pancreatitis is currently being elucidated. This may rest largely on the presence or absence of disorders commonly associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis, disorders which are known for their probable association with autoimmune pancreatitis, both have critically important associations with neoplasia. Whether autoimmune pancreatitis has a major association with eventual neoplasia should be assessed in major collaborative long-term studies.

From this patient’s clinical course and eventual diagnosis we concluded that in patients where tissue diagnosis has not proved malignancy and the CA 19-9 level is not high enough to have a high specificity, a caution should be exercised in relying only on CT scan features and marker levels in the diagnosis of cancer. In this situation, tissue diagnosis should be pursued and, if this is not conclusive, IgG4 testing should be considered so as to rule out autoimmune pancreatitis. In patients suspected of suffering autoimmune pancreatitis, strict follow up is recommended long after the inflammation has subsided following steroid treatment, as precancerous lesions might be concomitant with the pancreatitis and a association between these conditions has yet to be ruled out.

Peer reviewer: Wei Li, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, 1959 NE Pacific Street, Box 356410, Seattle, WA 98195, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Finkelberg DL, Sahani D, Deshpande V, Brugge WR. Autoimmune pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2670-2676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kamata N. Clinical difficulties in the differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2694-2699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Morris-Stiff G, Teli M, Jardine N, Puntis MC. CA19-9 antigen levels can distinguish between benign and malignant pancreaticobiliary disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:620-626. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Marrelli D, Caruso S, Pedrazzani C, Neri A, Fernandes E, Marini M, Pinto E, Roviello F. CA19-9 serum levels in obstructive jaundice: clinical value in benign and malignant conditions. Am J Surg. 2009;198:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bedi MM, Gandhi MD, Jacob G, Lekha V, Venugopal A, Ramesh H. CA 19-9 to differentiate benign and malignant masses in chronic pancreatitis: is there any benefit. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:24-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Steinberg W. The clinical utility of the CA 19-9 tumor-associated antigen. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:350-355. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mann DV, Edwards R, Ho S, Lau WY, Glazer G. Elevated tumour marker CA19-9: clinical interpretation and influence of obstructive jaundice. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:474-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ker CG, Chen JS, Lee KT, Sheen PC, Wu CC. Assessment of serum and bile levels of CA19-9 and CA125 in cholangitis and bile duct carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:505-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hardacre JM, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Sohn TA, Abraham SC, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, Choti MA, Campbell KA, Schulick RD, Hruban RH. Results of pancreaticoduodenectomy for lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2003;237:853-858; discussion 858-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kamisawa T, Imai M, Yui Chen P, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Suzuki M, Kamata N. Strategy for differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;37:e62-e67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chari ST, Takahashi N, Levy MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Topazian MA, Vege SS. A diagnostic strategy to distinguish autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1097-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sugumar A, Chari ST. Distinguishing pancreatic cancer from autoimmune pancreatitis: a comparison of two strategies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:S59-S62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lachter J, Cooperman JJ, Shiller M, Suissa A, Yassin K, Cohen H, Reshef R. The impact of endoscopic ultrasonography on the management of suspected pancreatic cancer--a comprehensive longitudinal continuous evaluation. Pancreas. 2007;35:130-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lachter J. Fatal complications of endoscopic ultrasonography: a look at 18 cases. Endoscopy. 2007;39:747-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khalid A, Nodit L, Zahid M, Bauer K, Brody D, Finkelstein SD, McGrath KM. Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspirate DNA analysis to differentiate malignant and benign pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2493-2500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lüttges J, Reinecke-Lüthge A, Möllmann B, Menke MA, Clemens A, Klimpfinger M, Sipos B, Klöppel G. Duct changes and K-ras mutations in the disease-free pancreas: analysis of type, age relation and spatial distribution. Virchows Arch. 1999;435:461-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Andea A, Sarkar F, Adsay VN. Clinicopathological correlates of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a comparative analysis of 82 cases with and 152 cases without pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:996-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Tada M, Ohashi M, Shiratori Y, Okudaira T, Komatsu Y, Kawabe T, Yoshida H, Machinami R, Kishi K, Omata M. Analysis of K-ras gene mutation in hyperplastic duct cells of the pancreas without pancreatic disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |