Published online Apr 27, 2012. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i4.96

Revised: February 27, 2012

Accepted: March 10, 2012

Published online: April 27, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the results of an aggressive surgical approach of resection and reconstruction of the inferior vena cava (IVC).

METHODS: The approach to caval resection depends on the extent and location of tumor involvement. The supra- and infra-hepatic portion of the IVC was dissected and taped. Left and right renal veins were also taped to control the bleeding. In 12 of the cases with partial tangential resection of the IVC, the flow was reduced to less than 40% so that the vein was primarily closed with a running suture. In 3 of the cases, the lumen of the vein was significantly reduced, requiring the use of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch. In 2 of the cases with segmental resection of the IVC, a PTFE prosthesis was used and in 1 case, the IVC was resected without reconstruction due to shunting the blood through the azygos and hemiazygos veins.

RESULTS: The mean operation time was 266 min (230-310 min) with an average intraoperative blood loss of 300 mL (200-2000 mL). The patients stayed in intensive care unit for 1.8 d (1-3 d). Mean hospital stay was 9 d (7-15 d). Twelve patients (66.7%) had no complications and 6 patients (33.3%) had the following complications: acute bleeding in 2 patients; bile leak in 2 patients; intra abdominal abscess in 1 patient; pulmonary embolism in 2 patients; and partial thrombosis of the patch in 1 patient. General complications such as pneumonia, pleural effusion and cardiac arrest were observed in the same group of patients. In all but 1 case, the complications were transient and successfully controlled. The mortality rate was 11.1% (n = 2). One patient died due to cardiac arrest and pulmonary embolism in the operation room and the second one died 2 d after surgery due to coagulopathy. With a median follow-up of 24 mo, 5 (27.8%) patients died of tumor recurrence and 11 (61.1%) are still alive, but three of them have a recurrence on computed tomography.

CONCLUSION: There are a variety of options for reconstruction after resection of the IVC that offers a higher resectable rate and better prognosis in selected cases.

- Citation: Vladov NN, Mihaylov VI, Belev NV, Mutafchiiski VM, Takorov IR, Sergeev SK, Odisseeva EH. Resection and reconstruction of the inferior vena cava for neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4(4): 96-101

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v4/i4/96.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v4.i4.96

Involvement of the inferior vena cava (IVC) has traditionally been considered as a contraindication for resection of advanced liver and retroperitoneal tumors because of the poor long-term prognosis and high surgical risks. The development of innovative surgical techniques, such as total hepatic vascular exclusion, veno-venous bypass and ex vivo hepatic resection, and the progress of liver transplantation has made a curative surgical approach to tumors involving both the liver and the IVC possible. The resected IVC can be primarily be repaired or reconstructed with synthetic or autogenous grafts.

From January 2008 to September 2010, 18 patients required resection of the IVC for malignancies presented in Table 1. There were 7 (38.9%) male patients and 11 (61.1%) female patients. The mean age of the patients was 58.8 years old (range 49 to 70). Tumor development was predominantly extracaval in 15 patients (83.3%) and 3 patients with leiomyosarcoma of the IVC. In most of the cases, the IVC was resected due to colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastases (n = 8), infiltration of hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 2), cholangiocarcinoma (n = 1), gall bladder cancer (n = 1) and pheochromocytoma of the right suprarenal gland (n = 1). In 2 of the cases, there were infiltration and thrombosis of the IVC by renal cell carcinoma of the right kidney.

| Diagnose | Sex | Age (yr) | Operation | Vascular resection |

| CRC metastases | F | 65 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential |

| CRC metastases | F | 61 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential |

| CRC metastases | M | 65 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential |

| CRC metastases | M | 52 | Sg V, VI, VII | Tangential |

| CRC metastases | F | 56 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential |

| CRC metastases | F | 70 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential |

| CRC metastases | F | 61 | Metastasectomy | Tangential |

| CRC metastases | F | 63 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential |

| HCC | F | 65 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential |

| HCC | M | 62 | Sg VII and VIII | Segmental + PTFE |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | F | 51 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential + patch |

| Gall bladder cancer | F | 68 | Sg IV, V and VI | Tangential |

| Leiomyosarcoma | F | 62 | Right hepatectomy | Tangential + patch |

| Leiomyosarcoma | M | 57 | Partial Sg VIII | Segmental + PTFE |

| Leiomyosarcoma | M | 49 | Resection | Tangential |

| Renal cell carcinoma | M | 63 | Right nephrectomy | Tangential |

| Renal cell carcinoma | M | 62 | Right nephrectomy | Segmental |

| Pheochromocytoma | F | 28 | Right suprarenalectomy | Tangential + patch |

The most common presenting symptom was pain in the upper abdomen in 12 patients. Edema of the lower extremities was observed in only 2 patients (11.7%), due to rich collaterals, and one patient (5.8%) presented with Budd-Chiari syndrome, with hepatomegaly, ascites and jaundice.

Abdominal Doppler ultrasound and angio-computed tomography (CT) were performed in all patients (100%). Ascending cavography by the femoral route was performed in 6 patients (33.3%) and selective arteriography of the celiac trunk in 3 patients (16.7%). Trans-esophageal echocardiography was performed in 4 patients (22.2%) in whom intracardiac extension was suspected. All the patients were thoroughly examined and preoperatively staged.

Surgery was performed through a superior midline and bilateral subcostal incision. In 2 patients with involvement of the suprahepatic IVC, an additional midline thoracotomy and pericardiotomy was used. A staging laparoscopy was performed in 3 patients. After mobilization of the liver, intraoperative Doppler ultrasound was performed. The approach to caval resection depended on the extent and location of tumor involvement. The supra- and infra-hepatic portion of the IVC was dissected and taped. Left and right renal veins were also taped to control the bleeding. In the cases of CRC metastases and liver resection, hepatic parenchyma was divided using the Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator and bipolar pincettes. The parenchyma transection was performed with inflow occlusion (Pringle maneuver) in 8 of the cases. Central venous pressure was kept at or below 5 cm H2O during parenchymal transection to minimize blood loss. Total vascular exclusion of the liver was performed in 5 of the patients. Warming therapy was applied to 16 patients to minimize intraoperative hypothermia.

In one of the cases with cancer of sigmoid colon (T3N1M1H3) and liver metastases in Sg 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, we performed resection of primary cancer combined with metastasectomies in the left liver and ligation of the right branch of the portal vein in the first operation. In the second operation, we performed a right hepatectomy with partial tangential resection of the IVC and resection of metastasis of segment 3.

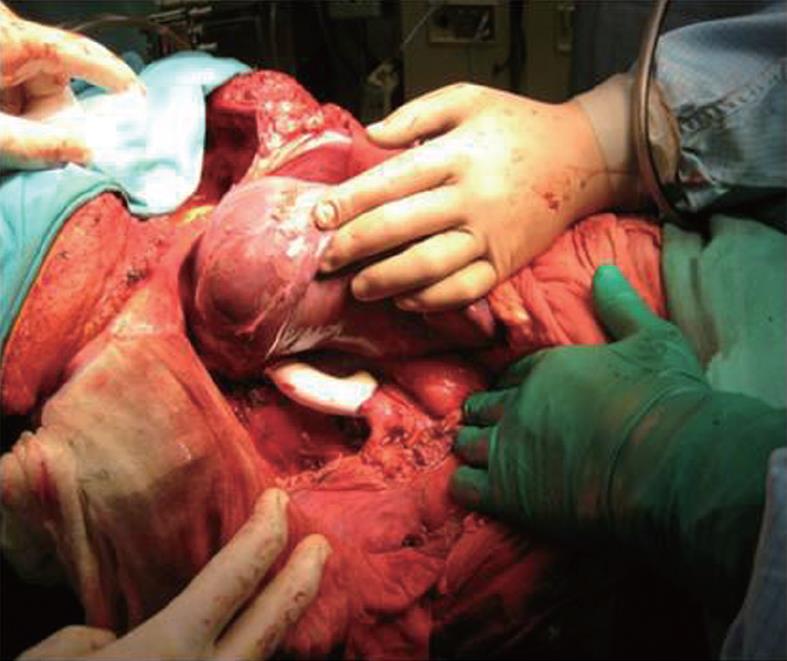

In 12 of the cases with partial tangential resection of the IVC, the flow was reduced to less than 40% so that the vein was primarily closed with a running suture (66.7%) (Figure 1).

In 3 of the cases, the lumen of the vein was significantly reduced, requiring the use of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch (16.7%). In 2 (11.1%) of the cases with segmental resection of the IVC, a PTFE prosthesis was used and in 1 case, the IVC was resected without reconstruction due to shunting the blood through the azygos and hemiazygous veins.

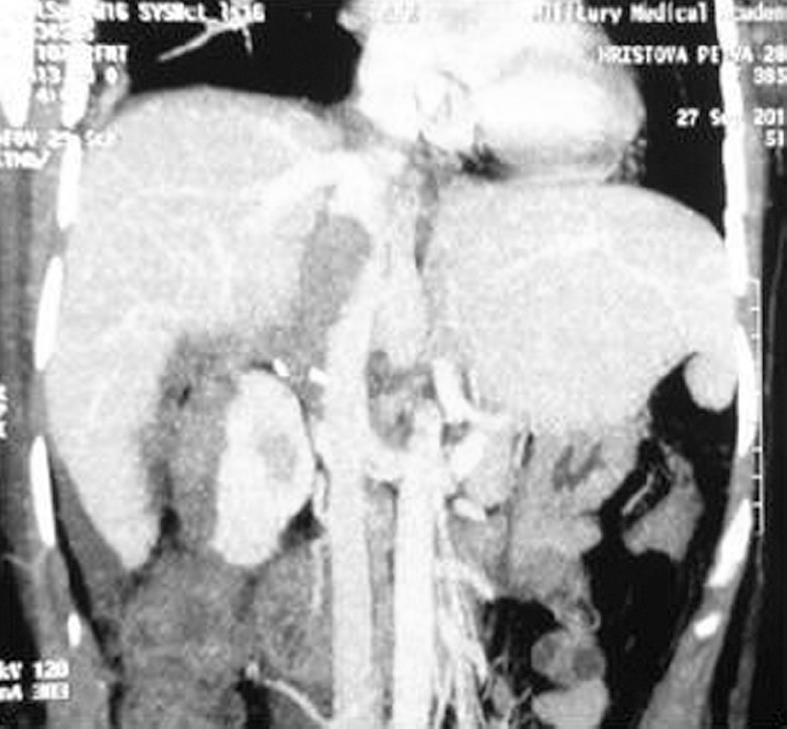

One of the patients with leiomyosarcoma of the IVC presented with edema of the lower extremities and Budd-Chiari syndrome. In this case, a resection of the retrohepatic vena cava with partial resection of Sg 8, thrombectomy from the middle and right hepatic veins was performed. For the reconstruction of the IVC, a PTFE prosthesis was used (Figure 2).

The mean operation time was 266 min (230-310 min) with an average intraoperative blood loss of 300 mL (200-2000 mL). The patients stayed in the intensive care unit for 1.8 d (1-3 d). Mean hospital stay was 9 d (7-15 d). Twelve patients (66.7%) had no complications and 6 patients (33.3%) had the following complications: acute bleeding in 2 patients; bile leak in 2 patients; intra abdominal abscess in 1 patient; pulmonary embolism in 2 patients; and partial thrombosis of the patch in 1 patient.

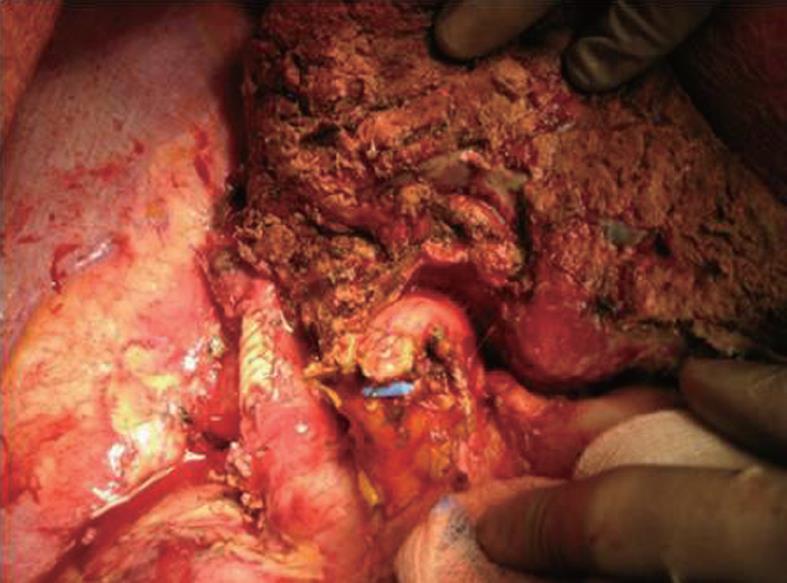

In one of the cases with PTFE patch reconstruction, we found a thrombosis at the place of the patch on the second postoperative day, which was successfully treated with anticoagulation therapy (Figures 3 and 4).

In the patient with advanced cholangiocarcinoma, we first performed ligation of the right branch of the portal vein due to insufficient liver volume in the left liver. One month later, a right hemihepatectomy with partial tangential resection of the IVC was performed. Six months later there is no evidence of recurrence (Figures 5 and 6).

General complications, such as pneumonia, pleural effusion and cardiac arrest, were observed in the same group of patients. In all but 1 case, the complications were transient and successfully controlled. The mortality rate was 11.1% (n = 2). One patient died due to cardiac arrest and pulmonary embolism in the operation room and the second one died 2 d after surgery due to coagulopathy. With a median follow-up of 24 mo, 5 (27.8%) patients died of tumor recurrence and 11 (61.1%) are still alive, but three of them have a recurrence on CT.

For patients with CRC liver metastases, liver resection offers the only potential for cure[1]. The ultimate goal in hepatic resection of colorectal metastases is to obtain negative histological margins. In the past, patients with involvement of the IVC were considered poor candidates for surgical management. Untreated patients, however, have a median survival of less than 12 mo[2]. Chemotherapy alone does not offer a curative option with few 5 years survivors reported[3]. Resection of liver tumors that involve the vena cava has become possible with lessons learned from liver transplantation. This aggressive surgical approach offers hope for patients with hepatic tumors involving the IVC, who would otherwise have a dismal prognosis. This procedure can be performed under total hepatic vascular exclusion, with or without veno-venous bypass, and by ex vivo resection[4]. Control of blood flow through the IVC is essential to facilitate resection and reconstruction. When involvement of the IVC is minimal (< 60° circumferentially and < 2 cm longitudinally), control may be simply achieved by applying a side clamp to the IVC. In our series, we used such an approach in 14 of the cases. When the estimated narrowing of the vein is less than 20%-40%, the IVC can be repaired primarily by a lateral suture[5].

More extensive involvement of the IVC requires the use of a patch or segmental resection with graft replacement. In such cases, TVE may be used[6-9]. This may be achieved by applying vascular clamps to the IVC below and above the liver, with concomitant interruption of hepatic blood inflow using a Pringle maneuver[10]. This approach is further facilitated by the tolerable prolonged periods (60-90 min) of continuous warm hepatic ischemia in patients with normal livers[8,11,12]. Attention should be paid to patients with cirrhotic livers, where the ischemic time is much shorter and the risk of bleeding is higher.

In 2 of our patients we used total graft replacement. The material of choice is PTFE[13-15]. TVE may significantly reduce cardiac output as a result of decreased venous return, possibly resulting in hemodynamic instability[16]. Systemic veno-venous bypass may restore venous return and cardiac output, but we did not use this in our group of patients. A proper anticoagulation therapy was used in all of the patients.

Leiomyosarcomas of the IVC are extremely rare, documented in the surgical literature mostly as case reports rather than organized series. Usually they have a slow growth so symptoms may be absent in the beginning. However, even with extensive caval involvement, severe venous obstructive symptoms are not often seen, probably because of the development of extensive venous collaterals, which maintain adequate flow around the level of obstruction[17]. The segment of the IVC between the renal veins and the hepatic veins is the most commonly affected location for all primary vascular tumors[18-20]. Resection with negative margins is the treatment of choice[18]. If negative margins can be achieved, extended venous resection does not influence local recurrence rate or long-term outcome[21]. Radical resection of the tumor en bloc with the affected segment of the vena cava has been shown to be a feasible option with improved survival in multiple studies[17-20,22,23]. However, such patients have a poor prognosis and over half of them who undergo radical resection develop tumor recurrence; the 5-year survival rate ranges between 31% and 62%[24]. Poor prognostic factors include suprahepatic location, presence of Budd-Chiari syndrome, intraluminal tumor growth and IVC occlusion[25]. Adjuvant therapy has not been shown to have a significant effect[18].

Caval management after IVC resection is controversial. Options include primary repair, autologous patching, ligation or reconstruction with a prosthetic graft. Extensive venous involvement and large tumor size often preclude short segment resection with simple repair or patching. Ligation of the IVC is favored by some and has been shown to be well tolerated and generally safe, especially in those with preoperative IVC thrombosis[18,22]. However, there is a risk of late complications such as pain, swelling and skin breakdown from severe lower extremity edema. Long-term anticoagulation may be necessary in these patients. Suprarenal IVC tumor involvement treated with IVC ligation can place a patient at serious risk for renal insufficiency. Restoration of flow to the right renal vein by reimplantation (or pelvic kidney autotransplantation) is mandatory to maintain right kidney function, but optional for the left renal vein because of the left kidney’s considerable collateral drainage through the adrenal, inferior phrenic, gonadal and paravertebral vessels[26]. Kieffer et al[19] used a proximal pressure reading of 30 mm Hg or more in the IVC as an indication for caval reconstruction and found reconstruction to be necessary in most cases. PTFE is the most commonly used prosthetic material and has been shown to be a suitable replacement for the IVC with excellent long-term patency[19,20,23,27,28]. Infection and graft thrombosis are the 2 major complications of this type of reconstruction but both are rare. Graft thrombosis may or may not have any clinical importance and methods used to decrease its incidence include the use of ring-reinforced PTFE to prevent compression, short-term anticoagulation and placement of an arterio-venous fistula to augment flow[19].

PTFE graft infection after IVC replacement has been shown to be a rare occurrence in several large series[19,20,23,27]. The treatment is usually conservative but in some cases the graft must be removed.

Direct extension of renal cell carcinoma into the vena cava has been found in 4% to 10% of patients undergoing nephrectomy to treat cancer[29,30]. The prognosis of RCC with IVC tumor thrombosis is difficult to predict due to a wide variety in clinical behavior[31]. Although involvement of the IVC in renal cancer is generally not a vascular invasion by the neoplastic process but mostly an intraluminal extension of the tumor mass, such intravascular growth implies a heightened biological behavior of the tumor. Early pulmonary metastases are found in most cases.

Resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with a negative microscopic margin improved survival. Thus, concomitant hepatic and IVC resection may provide a potentially curative operation. This aggressive surgical approach may offer hope for patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma involving the IVC[32,33].

In conclusion, it is apparent that application of combined resection of the liver and IVC expands the role of liver resection for malignancy and will benefit selected patients[34-36]. En bloc resection can be accomplished safely and confers an increase in survival for lesions often considered unresectable. There are a variety of options for replacement of the IVC if it cannot be primarily reconstructed. The use of various graft materials for reconstruction of the hepatic great vessels offers a higher resectable rate and better prognosis in selected cases. Such an operation should be performed in a specialized center where surgeons are familiar with both aspects of complex hepatobiliary surgery and liver transplantation.

Involvement of the major vessels has traditionally been considered as a contraindication for resection of advanced liver and retroperitoneal tumors because of the poor long-term prognosis and high surgical risks.

The development of innovative surgical techniques, such as total hepatic vascular exclusion,veno-venous bypass and ex vivo hepatic resection, and the progress of liver transplantation has made a curative surgical approach to tumors involving both the liver and inferior vena cava (IVC) possible.

The surgical removal of the tumor with clear margins is the only potential for cure. The advances in surgery and perioperative care lead to a more aggressive approach to malignancies involving major vessels which should be replaced by different kinds of allogen artificial grafts.

The use of vascular grafts after block resection of tumor and major vessels should be performed in specialized HPB and Transplant centers. The type of the graft depends on the hospital protocol and personal preferences of the surgeon.

Allograft is organ or tissue from one individual to another of the same species with a different genotype, including cadaveric or living related. A suitable vein is not always available and in this situation an artificial graft should be used.

The authors presented resection and reconstruction of the IVC for tumors. They conclude that the technique of combined resection of the liver and IVC is safe, expands the indication, and increases survival.

Peer reviewer: Kuniya Tanaka, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Yokohama City University, 3-9 Fukuura, Kanazawaku, Yokohama, Ktrj 112, Japan

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Adam R, Hoti E, Folprecht G, Benson AB. Accomplishments in 2008 in the management of curable metastatic colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2009;3:S15-S22. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rougier P, Milan C, Lazorthes F, Fourtanier G, Partensky C, Baumel H, Faivre J. Prospective study of prognostic factors in patients with unresected hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Fondation Française de Cancérologie Digestive. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1397-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Isenberg J, Fischbach R, Krüger I, Keller HW. Treatment of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:1291-1295. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lodge JP, Ammori BJ, Prasad KR, Bellamy MC. Ex vivo and in situ resection of inferior vena cava with hepatectomy for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2000;231:471-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liao GS, Hsieh HF, Hsieh CB, Chen TW, Chen CJ, Yu JC, Li YC. Vessel reconstruction for great vessel invasion by hepatobiliary malignancy. J Med Sci. 2005;25:309-312. |

| 6. | Heaney JP, Stanton WK, Halbert DS, Seidel J, Vice T. An improved technic for vascular isolation of the liver: experimental study and case reports. Ann Surg. 1966;163:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fortner JG, Shiu MH, Kinne DW, Kim DK, Castro EB, Watson RC, Howland WS, Beattie EJ. Major hepatic resection using vascular isolation and hypothermic perfusion. Ann Surg. 1974;180:644-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huguet C, Nordlinger B, Galopin JJ, Bloch P, Gallot D. Normothermic hepatic vascular exclusion for extensive hepatectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;147:689-693. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Berney T, Mentha G, Morel P. Total vascular exclusion of the liver for the resection of lesions in contact with the vena cava or the hepatic veins. Br J Surg. 1998;85:485-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pringle JH. V. Notes on the Arrest of Hepatic Hemorrhage Due to Trauma. Ann Surg. 1908;48:541-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 855] [Cited by in RCA: 841] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nagasue N, Yukaya H, Ogawa Y, Hirose S, Okita M. Segmental and subsegmental resections of the cirrhotic liver under hepatic inflow and outflow occlusion. Br J Surg. 1985;72:565-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huguet C, Gavelli A, Bona S. Hepatic resection with ischemia of the liver exceeding one hour. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:454-458. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Huguet C, Ferri M, Gavelli A. Resection of the suprarenal inferior vena cava. The role of prosthetic replacement. Arch Surg. 1995;130:793-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sarkar R, Eilber FR, Gelabert HA, Quinones-Baldrich WJ. Prosthetic replacement of the inferior vena cava for malignancy. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:75-81; discussion 82-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bower TC, Nagorney DM, Toomey BJ, Gloviczki P, Pairolero PC, Hallett JW, Cherry KJ. Vena cava replacement for malignant disease: is there a role. Ann Vasc Surg. 1993;7:51-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Delva E, Barberousse JP, Nordlinger B, Ollivier JM, Vacher B, Guilmet C, Huguet C. Hemodynamic and biochemical monitoring during major liver resection with use of hepatic vascular exclusion. Surgery. 1984;95:309-318. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Dzsinich C, Gloviczki P, van Heerden JA, Nagorney DM, Pairolero PC, Johnson CM, Hallett JW, Bower TC, Cherry KJ. Primary venous leiomyosarcoma: a rare but lethal disease. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15:595-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hollenbeck ST, Grobmyer SR, Kent KC, Brennan MF. Surgical treatment and outcomes of patients with primary inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:575-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kieffer E, Alaoui M, Piette JC, Cacoub P, Chiche L. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: experience in 22 cases. Ann Surg. 2006;244:289-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hines OJ, Nelson S, Quinones-Baldrich WJ, Eilber FR. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: prognosis and comparison with leiomyosarcoma of other anatomic sites. Cancer. 1999;85:1077-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mingoli A, Sapienza P, Cavallaro A, Di Marzo L, Burchi C, Giannarelli D, Feldhaus RJ. The effect of extend of caval resection in the treatment of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:3877-3881. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Mingoli A, Feldhaus RJ, Cavallaro A, Stipa S. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: analysis and search of world literature on 141 patients and report of three new cases. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:688-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Illuminati G, Calio' FG, D'Urso A, Giacobbi D, Papaspyropoulos V, Ceccanei G. Prosthetic replacement of the infrahepatic inferior vena cava for leiomyosarcoma. Arch Surg. 2006;141:919-924; discussion 924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ito H, Hornick JL, Bertagnolli MM, George S, Morgan JA, Baldini EH, Wagner AJ, Demetri GD, Raut CP. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: survival after aggressive management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3534-3541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mingoli A, Cavallaro A, Sapienza P, Di Marzo L, Feldhaus RJ, Cavallari N. International registry of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: analysis of a world series on 218 patients. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:3201-3205. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kraybill WG, Callery MP, Heiken JP, Flye MW. Radical resection of tumors of the inferior vena cava with vascular reconstruction and kidney autotransplantation. Surgery. 1997;121:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Dew J, Hansen K, Hammon J, McCoy T, Levine EA, Shen P. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: surgical management and clinical results. Am Surg. 2005;71:497-501. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Bower TC, Nagorney DM, Cherry KJ, Toomey BJ, Hallett JW, Panneton JM, Gloviczki P. Replacement of the inferior vena cava for malignancy: an update. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:270-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Skinner DG, Vermillion CD, Colvin RB. The surgical management of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1972;107:705-710. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Kearney GP, Waters WB, Klein LA, Richie JP, Gittes RF. Results of inferior vena cava resection for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1981;125:769-773. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Kaplan S, Ekici S, Doğan R, Demircin M, Ozen H, Paşaoğlu I. Surgical management of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombus. Am J Surg. 2002;183:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Kurosawa H, Kimura F, Ito H, Shimizu H, Togawa A, Otsuka M, Yoshidome H, Kato A, Miyazaki M. Right hepatectomy combined with retrohepatic caval resection, using a left renal vein patch graft for advanced cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:362-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nakagohri T, Konishi M, Inoue K, Oda T, Kinoshita T. Extended right hepatic lobectomy with resection of inferior vena cava and portal vein for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:599-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Felix EL, Wood DK, Das Gupta TK. Tumors of the retroperitoneum. Curr Probl Cancer. 1981;6:1-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Huguet C, Gavelli A. Total vascular exclusion for liver resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:368-369. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Scheele J, Stang R, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Paul M. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:59-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1106] [Cited by in RCA: 1024] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |