Published online Apr 27, 2012. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i4.102

Revised: November 27, 2011

Accepted: December 10, 2011

Published online: April 27, 2012

Primary colonic lymphomas represent a rare minority among the colonic neoplasms. Their correct pre-operative identification is crucial for the design of treatment. We herein describe a case of a colonic lymphoma presenting as a necrotic colonic mass and we discuss the current evidence about the presentation, diagnosis and treatment of lymphomas isolated to the colon.

- Citation: Konstantinidis IT, Probstfeld MR. Lymphoma presenting as a necrotic colonic mass. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4(4): 102-103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v4/i4/102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v4.i4.102

Colonic lymphomas represent a rare entity, comprising less than 1% of colonic neoplasms. Their correct treatment is still an issue of debate as the rarity of this disease precludes randomized clinical trials. In this report, we describe a case of a colonic lymphoma presenting as a necrotic colonic mass and we emphasize the correct identification of colonic lymphomas and the current evidence with regard to their treatment.

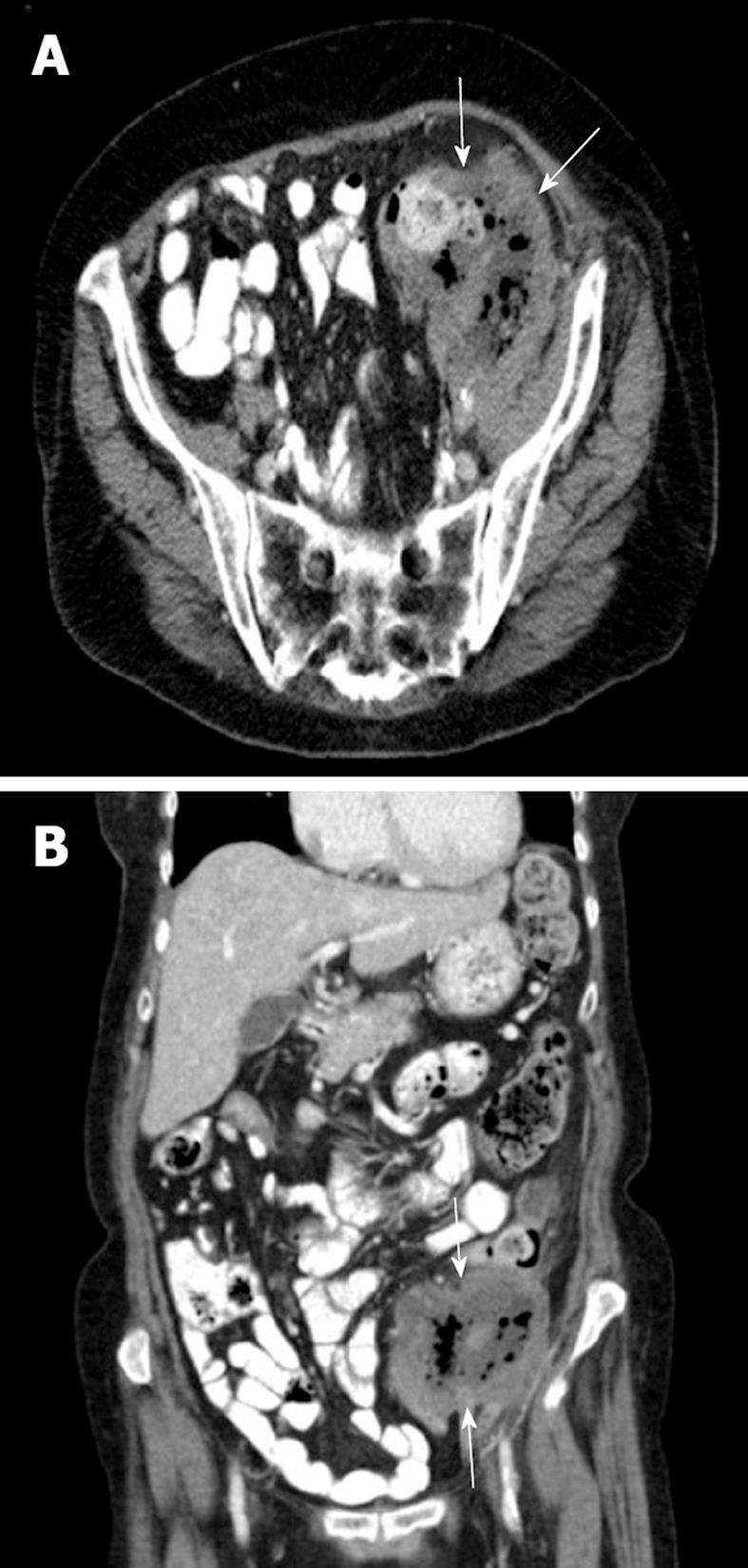

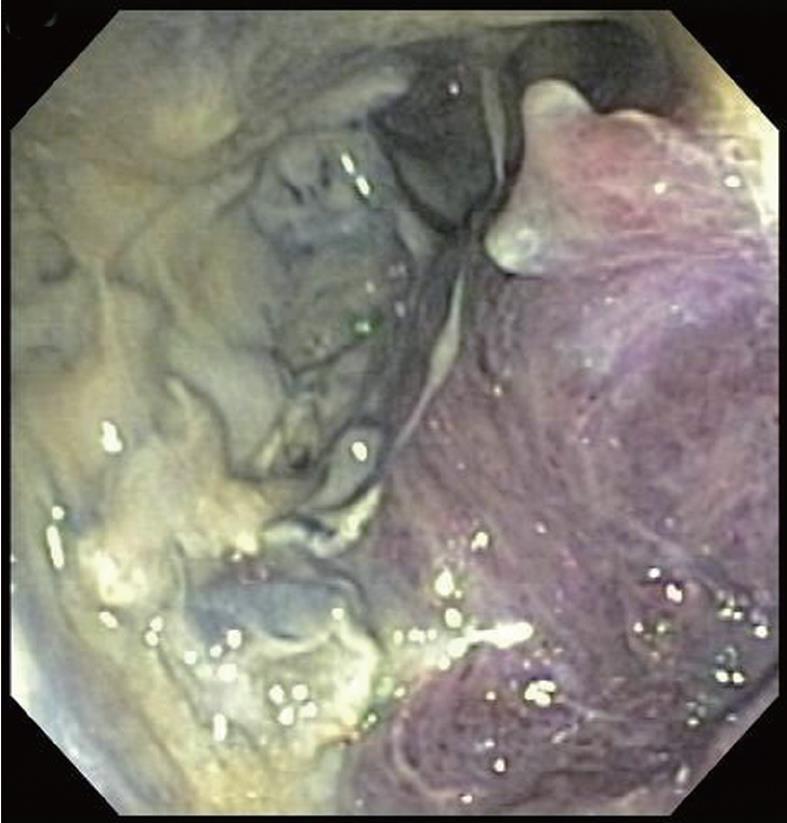

A 70-year-old female presented with a 6-mo history of vague abdominal pain. The patient also complained of constipation, fatigue and night sweats but no nausea, vomiting, weight loss or melena. The patient’s medical history included breast cancer status post lumpectomy 10 years ago and splenic lymphoma status post splenectomy 6 years ago. Her last colonoscopy was 6 years ago and was normal. The abdomen was soft, tender to palpation over the left lower quadrant with no rebound or guarding. An 8-10 cm abdominal mass was palpable at the left lower quadrant. The laboratory results showed a white cell count of 13 000 per cubic millimeter and a carcino-embryonic antigen level of 0.7 ng/mL. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with oral and intravenous contrast medium showed a necrotic mass 8.7 cm × 9.4 cm at the left lower quadrant, encasing the distal descending and proximal sigmoid colon, with associated adenopathy in the retroperitoneum and left sided hydronephrosis secondary to ureteral obstruction by the mass (Figure 1A and B, arrows). A colonoscopy was consistent with a large necrotic and ulcerated mass in the sigmoid colon (Figure 2).

Biopsies obtained during the colonoscopy were consistent with B-cell lymphoma. The patient underwent surgical exploration and proximal colostomy with the plan to follow up with systemic chemotherapy and surgery after the conclusion of the chemotherapy.

Primary colonic lymphomas account for only 0.2%-0.6% of colon cancers[1-5] and 10%-20% of the gastrointestinal lymphomas, with the stomach by far the most common site[1,6]. Colonic lymphomas are found more frequently in males in their sixth and seventh decade of life[1,3,5]. Inflammatory bowel disease and immunosuppressive states like HIV are known risk factors[1,5]. The most frequent presentation is abdominal pain and weight loss, whereas an abdominal mass, as in our case, is often palpable[1-3,5]. The most commonly involved site is the cecum, likely because of the abundance of lymphoid tissue in the ileocecal region[1-5]. The predominant type is non-Hodgkins B cell lymphoma[1,3,4].

In our case, the lymphoma presented as a necrotic colonic mass on computerized tomography. In general, the CT appearance of lymphomas can be that of either a discrete mass, focal induration or diffuse colonic invasion[7]. The presence of extensive abdominal and/or pelvic lymphadenopathy places the lymphoma at the top of the differential diagnosis. Even in the absence of lymphadenopathy, imaging characteristics such as location at the cecum, demarcation from the peri-colonic fat with no invasion of surrounding viscera and the presence of perforation in the absence of desmoplastic reaction should raise the suspicion of a lymphoma[7]. The role of colonoscopy and biopsy is crucial for the correct pre-operative diagnosis.

Most of the tumors present in an advanced stage and the reported 5-year survival is thus relatively poor, ranging between 27%-55%[1-6]. Most of the reported series use a combination of surgery and chemotherapy[3]. Although the exact role of chemotherapy cannot be defined due to the rarity of the disease and the lack of randomized trials, some authors support that it is associated with a survival benefit[1,4]. In the presence of a colonic perforation, which may occur during the chemotherapy, the mortality is high[4]. In the report by Lai et al[4], the four patients who were operated emergently for perforation died within 30 d post-operatively. In our case, we elected to offer a proximal colostomy, given the extent of the disease, and to proceed with chemotherapy. We plan to resect the remnant tumor and restore the continuity of the GI tract after completion of the chemotherapy.

Peer reviewer: John H Stewart, MD, Department of Surgery, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Dionigi G, Annoni M, Rovera F, Boni L, Villa F, Castano P, Bianchi V, Dionigi R. Primary colorectal lymphomas: review of the literature. Surg Oncol. 2007;16 Suppl 1:S169-S171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zighelboim J, Larson MV. Primary colonic lymphoma. Clinical presentation, histopathologic features, and outcome with combination chemotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;18:291-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wong MT, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:586-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lai YL, Lin JK, Liang WY, Huang YC, Chang SC. Surgical resection combined with chemotherapy can help achieve better outcomes in patients with primary colonic lymphoma. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:265-268. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Fan CW, Changchien CR, Wang JY, Chen JS, Hsu KC, Tang R, Chiang JM. Primary colorectal lymphoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1277-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3861-3873. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wyatt SH, Fishman EK, Hruban RH, Siegelman SS. CT of primary colonic lymphoma. Clin Imaging. 1994;18:131-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |