Published online Mar 27, 2012. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i3.73

Revised: March 3, 2012

Accepted: March 10, 2012

Published online: March 27, 2012

Schwannoma is predominantly a benign neoplasm of the Schwann cells in the neural sheath of the peripheral nerves. Occurrence of schwannoma in parenchymatous organs, such as liver, is extremely rare. A 64-year-old man without neurofibromatosis was observed to have a space-occupying lesion of 23mm diameter in the liver during follow-up examination for a previously resected gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the small intestine. He underwent lateral segmentectomy of the liver under a provisional diagnosis of hepatic metastatic recurrence of the GIST. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of a benign schwannoma, confirmed by characteristic pathological findings and positive immunoreactions with the neurogenic marker S-100 protein, but negative for c-kit, or CD34. The tumor was the smallest among the reported cases. When the primary hepatic schwannoma is small in size, preoperative clinical diagnosis is difficult. Therefore, this disease should be listed as differential diagnosis for liver tumor with clinically benign characteristics.

- Citation: Hayashi M, Takeshita A, Yamamoto K, Tanigawa N. Primary hepatic benign schwannoma. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4(3): 73-78

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v4/i3/73.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v4.i3.73

Schwannoma, also referred to as neurilemomas, neurinomas, and perineural fibroblastomas, which may occur in patients with and without neurofibromatosis, is predominantly a benign neoplasm of the Schwann cells in the neural sheath of cranial and peripheral nerves. They are usually occur in the extremities, but can also be found in the head and neck, trunk, pelvis, retroperitoneum, mediastinum and gastrointestinal tract, but they are extremely uncommon in parenchymatous organs, such as liver and pancreas[1].

Primary hepatic benign schwannoma was first reported by Pereira et al[2] in 1978, and a literature search of Medline and PubMed, from 1960 to 2010, with the key words “hepatic schwannoma” and “liver schwannoma” yielded only 14 cases reported to date.

Herein, we report the case of a 64-year-old male with benign hepatic schwannoma without neurofibromatosis. The tumor was successfully removed surgically and the disease was confirmed pathologically. We also reviewed the reported cases in the literature and discuss the key points in terms of clinical, pathological, and radiological aspects of this entity.

A 64-year-old Japanese man was pointed out to have a space-occupying lesion in the liver during the follow-up examination for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the small intestine.

His past history was significant: previous operation for right hepatectomy for liver cyst 22 years before and resection of the small intestine for GIST 6 years before, for which no adjuvant therapy was administered. He had neither present history nor family history of neurofibromatosis. Physical examination revealed no abnormal finding, including skin lesions, suggesting neurofibromatosis. Findings of blood examination were almost normal, including blood cell counts, serum biochemistry, and tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein, protein induced by vitamin-K absence or antagonist II (PIVKA-II), carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

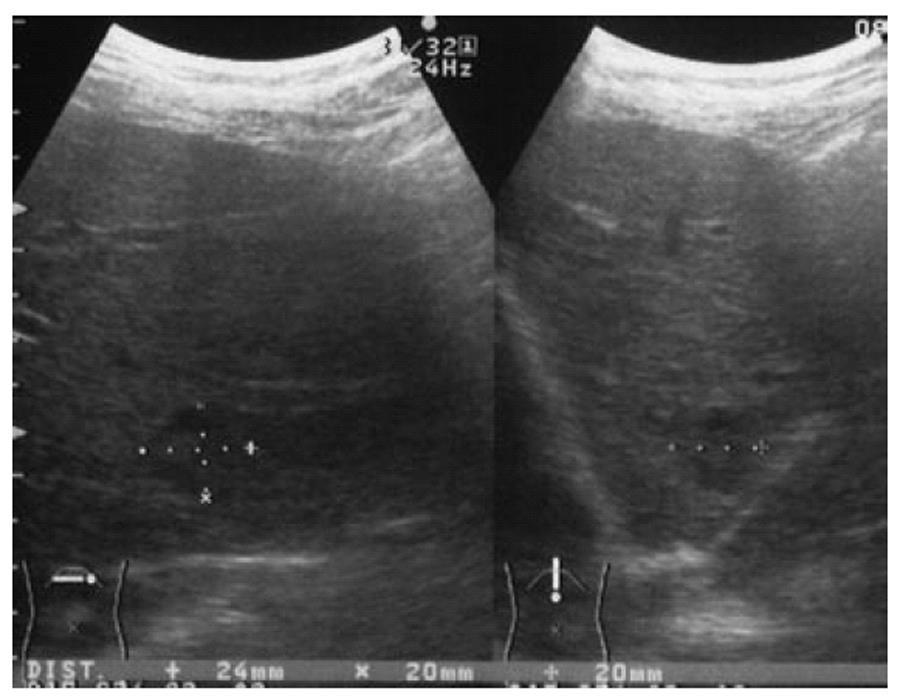

Abdominal ultrasonography (Figure 1) showed a 24-mm diameter mixed echo pattern of iso- and hypoechoic mass without hallo in segment (S) 2 of the liver; these results were not typical for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or metastatic tumor.

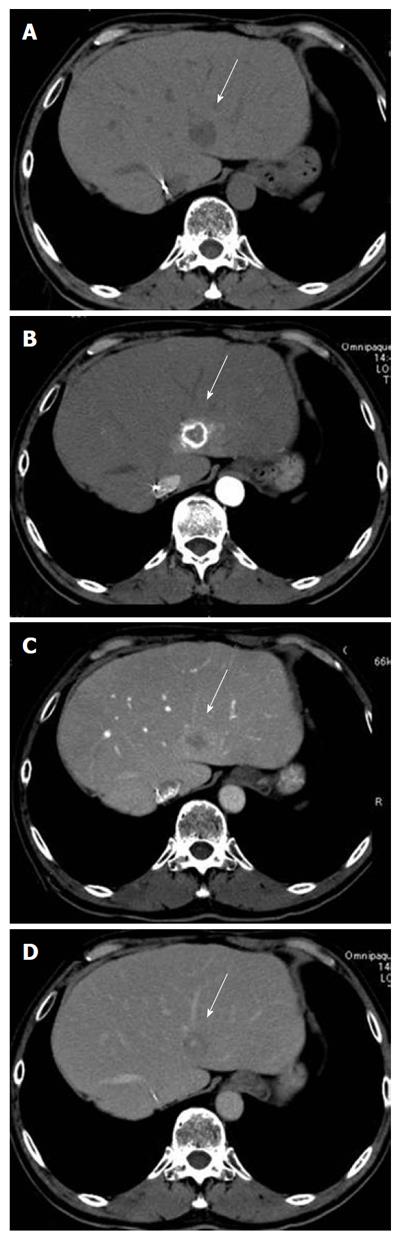

Abdominal computed tomography (CT, Figure 2) showed a 2-cm-diameter low density lesion before contrast material injection in the S2 of the liver, which was ring-enhanced in the early arterial phase (Figure 2B) and subsequently washed out in the portal phase after contrast material injection (Figure 2C). Other organs including regional or para-aortic lymph nodes showed no abnormal results.

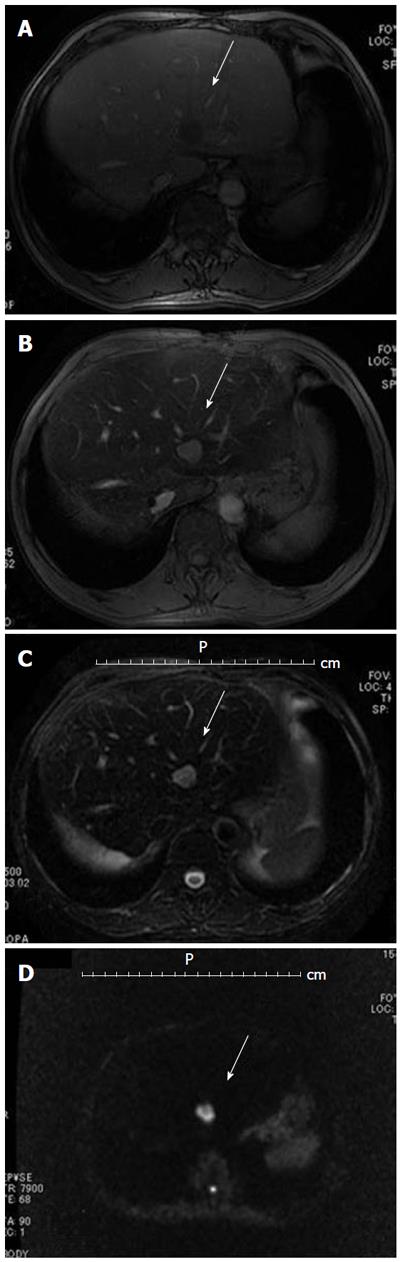

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, Figure 3) also showed a 2-cm tumor in segment 2 of the liver, which was low signal intensity in T1-weigted imaging (Figure 3B), high signal intensity in T2-weigted imaging (Figure 3C), and low intensity in hepatobiliary phase 20 min after injection of gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA, Primovist, Bayer Schering Pharma), and on dynamic Gd-EOB-DTPA MRI protocol not clearly visualized during arterial dominant phase and slight ring-like enhancement persisted, indicating hypovascular tumor, such as cholangiocarcinoma or liver metastasis.

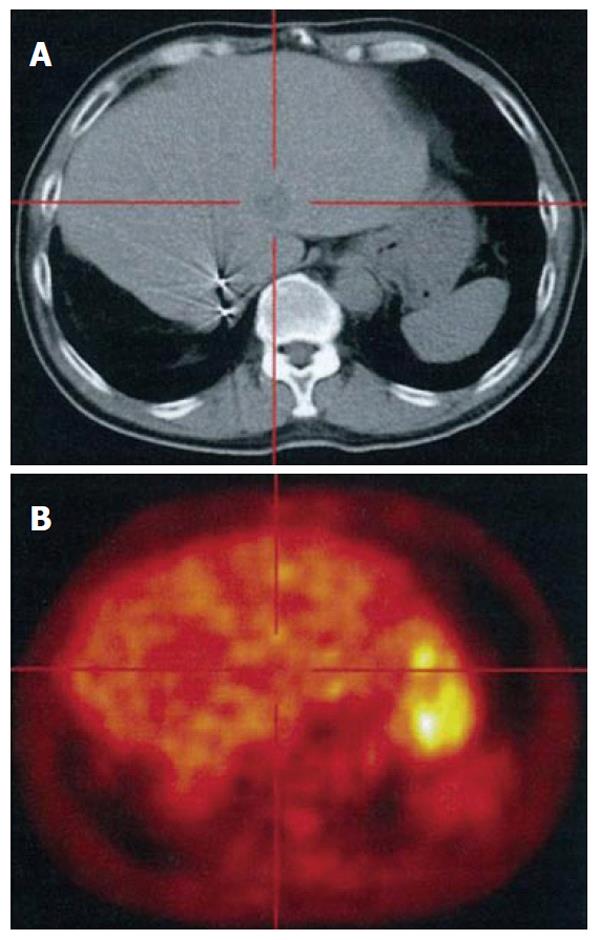

In a fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography examination integrated with computed tomography scanning (FDG-PET CT, Figure 4), the tumor did not show significant FDG uptake, suggesting the benign nature of the tumor except for well-differentiated HCC.

Although imaging studies showed no remarkable findings on other organs indicating likely primary occurrence, given the previous history of GIST metastatic recurrence in the liver was initially suspected.

With a clinical diagnosis of metastatic liver tumor from GIST, partial hepatectomy of S2 was performed. The resected specimen showed a tumor of 23 mm in diameter (Figure 5). The excised section of the tumor showed only a solid component, without a cystic component or apparent capsule.

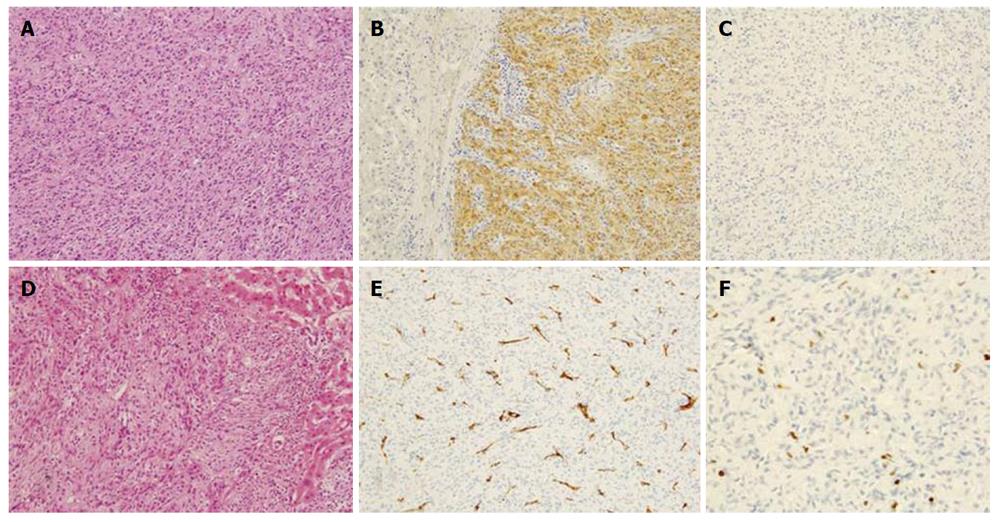

Histological examination showed a tumor without fibrous capsule with interlacing bands of uniform spindle cells of which elongated nuclei were arranged in a palisading pattern. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed tumor cells were diffusely positive for S-100, but negative for c-kit, or CD34. The Ki-67 index was 2% (Figure 6). The hepatic tumor was diagnosed as benign schwannoma, since the Ki-67 index was lower than 5%, which is the reported criterion proposed for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. The jejunal GIST, which had been surgically removed 6 years before, was a 10 cm x 6 cm tumor, and immunohistochemical analysis revealed c-kit (+), CD34 (-), desmin (-), α-smooth muscle actin (±), S-100 (-), and Ki-67 labeling index was 3%. Considering these results, the hepatic tumor was not secondary to the jejunal GIST, but a primary neoplasm originating from the liver.

The postoperative course was uneventful and he was discharged from hospital on postoperative day 16. He is currently doing well with no sign of relapse 27 mo after the surgery.

The exact etio-pathogenesis of schwannoma remains unclear. Up to 20% of cases are associated with neurofibromatosis Type 1[3]. The most affected sites are the flexor surface of extremities, head and neck, but schwannoma can also be found in the trunk, pelvis, retroperitoneum, and mediastinum. It can develop infrequently in the gastrointestinal tract including stomach and rectum, but is exceedingly uncommon in the liver[1].

The hepatobiliary nerves originating from the hepatic plexus in the liver hilum and composed of sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) fibers, a few of which are also distributed among the interlobular connective tissues along the portal veins, are the origin of this neoplasm in the hepatic parenchyma[4-6].

Accordingly, the porta hepatis is reported to be one of the occurrence sites of this tumor, since the nerve sheath is abundant in the hepatoduodenal ligament[7]. Extrahepatic biliary schwannoma have been reported in 9 cases, with 3 cases in porta hepatis, and one case in the hepatoduodenal ligament[8].

Occurrence of schwannoma at both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts has also been reported[9]. The mean age at the time of diagnosis was 57.5 years (range: 38-70 years) and the male-to-female (M:F) ratio was 4:11 a slight female predominance[1,2,4-6,10-17].

Clinical symptoms and signs vary depending on the anatomical site and the size of the tumor although most schwannomas present as an asymptomatic or painless mass. In the case of a tumor located at the porta hepatis, obstructive jaundice may occur as the initial clinical symptom on presentation[4].

The literature describes tumors varying from 2.3 cm (present case) to 24 cm in size, with a median of approximately 13 cm. However, the current advancement of imaging modalities has resulted in tumors of smaller size at the time of diagnosis being reported in the most recent cases, where 5 out of 6 consecutive cases had tumors less than 5cm in size.

Usually, these tumors show slow and expansive growth, in contrast to some malignant cases in which invasion and involvement of contiguous organs has been reported to occur[18]. However, with schwannoma malignant transformation is reported only sporadically and thought to be rare[19,20]. Further, malignant schwannoma of liver origin not associated with neurofibromatosis has been reported only extremely rarely[20,21].

Histological examination in conjunction with immunohistochemistry is essential for diagnosis. Pathologically, schwannomas are encapsulated tumors that arise within the nerve sheaths and consist of a highly ordered cellular component (Antoni type A area) and a loose myxoid component (Antoni type B area), with varying relative amounts of these two elements[22]. The former is composed of spindle-shaped Schwann cells arranged in interlacing fascicles, and the latter consists of a loose meshwork of gelatinous and microcystic tissue[8]. Occasionally these may degenerate and become cystic because of either hemorrhage or necrosis. Schwannomas can also be quite hypervascular. The presence of encapsulation, the two types of Antoni areas, connective tissue fragments (Verocay bodies), and uniformly intense immunostaining for S-100 protein, which is specific for Schwann cell, distinguish schwannomas from neurofibromas, GIST, and leiomyomas[23].

The radiologic appearance of schwannomas varies depending on the distribution of the different histologies (Antoni A and Antoni B areas) and the degree or type of degeneration[7]. Imaging diagnosis is still challenging in cases of early stage disease. Since the tumor size of 2 cm in the current patient was much smaller than those of reported cases (median diameter of 13 cm), we could not conclusively obtain a preoperative diagnosis. When the tumor size increases, CT depicts a non-homogenous area on plain study and a clearly enhanced margin and an irregular pattern inside the tumor on contrast study[4], reflecting secondary morphological alterations including cystification, calcification, hemorrhage, and necrosis. The majority of tumors less than 5 cm in size show no cystic degeneration (3 out of 4 cases). On MRI, tumors appear hypointense in T1-weighted images and mixed hypo- and hyperintense in T2-weighted images. In serial contrast-enhanced images, the lesion shows gradually increasing centrilobular enhancement[17].

With respect to the significance of FDG-PET, the recent 2 reports[5,6] demonstrated positive uptake of FDG at the tumor site, while this was not the case in our patient, presumably due to the lower grade of inflammatory activity or lower cellularity in the current case. FDG-PET would not, therefore, be adequate as a sole diagnostic tool for differentiating schwannomas from malignant lesions of the liver[6].

The treatment for benign schwannoma is usually complete excision. The prognosis is good, with no recurrence being reported so far, and additional treatment is unnecessary[23]. Recurrence is unusual even following incomplete removal, and malignant transformation is exceedingly rare[16].

In the majority of reported case, diagnosis was made after a tumor resection with confirmation by postoperative immunohistochemical examination of the tumor. Preoperative clinical diagnosis is still difficult, especially when the tumor small, as in the present case, due to the lack of characteristic clinical and imaging manifestations. Therefore, this disease should be listed as a differential diagnosis for liver tumors with benign clinical characteristics.

Peer reviewer: Salvatore Gruttadauria, MD, PhD, Abdominal Transplant Surgery, ISMETT-UPMC, Via E. Tricomi N. 1, 90127 Palermo, Italy

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Hytiroglou P, Linton P, Klion F, Schwartz M, Miller C, Thung SN. Benign schwannoma of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:216-218. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Pereira Filho RA, Souza SA, Oliveira Filho JA. Primary neurilemmal tumour of the liver: case report. Arq Gastroenterol. 1978;15:136-138. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Theodosopoulos T, Stafyla VK, Tsiantoula P, Yiallourou A, Marinis A, Kondi-Pafitis A, Chatziioannou A, Boviatsis E, Voros D. Special problems encountering surgical management of large retroperitoneal schwannomas. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wada Y, Jimi A, Nakashima O, Kojiro M, Kurohiji T, Sai K. Schwannoma of the liver: report of two surgical cases. Pathol Int. 1998;48:611-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee WH, Kim TH, You SS, Choi SP, Min HJ, Kim HJ, Lee OJ, Ko GH. Benign schwannoma of the liver: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:727-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim YC, Park MS. Primary hepatic schwannoma mimicking malignancy on fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Hepatology. 2010;51:1080-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Choi H, Whitman G, Ro J, Charnsangavej C. Benign schwannoma in the porta hepatis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:652. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kulkarni N, Andrews SJ, Rao V, Rajagopal KV. Case report: Benign porta hepatic schwannoma. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2009;19:213-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Madhusudhan KS, Srivastava DN, Dash NR, Gupta C, Gupta SD. Case report. Schwannoma of both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts: a rare case. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:e212-e215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoshida M, Nakashima Y, Tanaka A, Mori K, Yamaoka Y. Benign schwannoma of the liver: a case report. Nihon Geka Hokan. 1994;63:208-214. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Heffron TG, Coventry S, Bedendo F, Baker A. Resection of primary schwannoma of the liver not associated with neurofibromatosis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:1396-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Flemming P, Frerker M, Klempnauer J, Pichlmayr R. Benign schwannoma of the liver with cystic changes misinterpreted as hydatid disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1764-1766. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kapoor S, Tevatia MS, Dattagupta S, Chattopadhyay TK. Primary hepatic nerve sheath tumor. Liver Int. 2005;25:458-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ozkan EE, Guldur ME, Uzunkoy A. A case report of benign schwannoma of the liver. Intern Med. 2010;49:1533-1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Akin M, Bozkirli B, Leventoglu S, Unal K, Kapucu LO, Akyurek N, Sare M. Liver schwannoma incidentally discovered in a patient with breast cancer. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2009;110:298-300. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Momtahen AJ, Akduman EI, Balci NC, Fattahi R, Havlioglu N. Liver schwannoma: findings on MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:1442-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sheikh MY, Husen YA, Pervez S, Khalid TR, Jaffer N, Afzal M. Computed tomography appearance of malignant schwannoma of the liver. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1996;47:183-185. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lederman SM, Martin EC, Laffey KT, Lefkowitch JH. Hepatic neurofibromatosis, malignant schwannoma, and angiosarcoma in von Recklinghausen's disease. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:234-239. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Fiel MI, Schwartz M, Min AD, Sung MW, Thung SN. Malignant schwannoma of the liver in a patient without neurofibromatosis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1145-1147. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Morikawa Y, Ishihara Y, Matsuura N, Miyamoto H, Kakudo K. Malignant schwannoma of the liver. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1279-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nakajima M. [Neurofibroma of the liver, schwannoma of the liver]. Ryoikibetsu Shokogun Shirizu. 1995;381-383. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Eizinger FM, Weiss SW. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. Soft tissue tumors. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995; 829-842. |